Stephane Klecha is Managing Partner at Klecha and Co., a European private investment bank focused on technology, software, IT services, hardware and IoT, and a former Vice President of Lazard, a global financial advisory and asset management firm. Brunello Rosa is Co-founder, CEO, and Head of Research at Roubini & Rosa Associates, a consultancy firm providing independent research and advisory services, and is a Visiting Professor in Cyber Risk Strategy and Governance at Bocconi University You may follow him on Twitter @brunello_rosa. Nouriel Roubini is Professor of Economics at New York University’s Stern School of Business. He is also CEO of Roubini Macro Associates, a global macroeconomic consultancy firm, and Co-Founder of Rosa & Roubini Associates. You may follow him on Twitter @Nouriel. The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Arlind Rama to the section on Western Balkans.

Stephane Klecha is Managing Partner at Klecha and Co., a European private investment bank focused on technology, software, IT services, hardware and IoT, and a former Vice President of Lazard, a global financial advisory and asset management firm. Brunello Rosa is Co-founder, CEO, and Head of Research at Roubini & Rosa Associates, a consultancy firm providing independent research and advisory services, and is a Visiting Professor in Cyber Risk Strategy and Governance at Bocconi University You may follow him on Twitter @brunello_rosa. Nouriel Roubini is Professor of Economics at New York University’s Stern School of Business. He is also CEO of Roubini Macro Associates, a global macroeconomic consultancy firm, and Co-Founder of Rosa & Roubini Associates. You may follow him on Twitter @Nouriel. The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Arlind Rama to the section on Western Balkans.

As the European Union, together with the rest of the world, begins to emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic, it seems opportune to examine how European integration has progressed in the last few years, in spite of Brexit, on various fronts: economic, military/security, and technological.

In this respect, technology is the issue and the solution at the same time. It is the issue because Europe still needs to catch up with United States and China in terms of the size of its digital giants and the presence of a unified regulatory and technological landscape that is able to harmonize its various national standards. It is the solution because technology can help break the physical barriers that prevent a complete integration of the continent and the establishment of proper EU sovereignty. Data sovereignty is the first building block towards establishing a well-rounded EU digital sovereignty, as a stepping-stone towards a complete integration of the continent.

Reacting to Setbacks

The EU integration process has been characterized by a series of setbacks, which have then been followed by important advances. Recent ones include the migrant crisis of 2015, the Brexit referendum in 2016, resurfacing euro re-denomination risks in 2018-2019, and finally the COVID-induced crisis that began in 2020. All these events occurred while internationalism was deteriorating, amid the victory of an isolationist American president, mounting trade and geopolitical tensions between major economies, the ongoing balkanization of global supply and value chains, and an underlying technological conflict between the United States and China (in which Russia and the EU were inevitably engaged). The resulting polarization of the world into spheres of influence dominated by the United States and China amounts to what has been labelled Cold War 2.0.

Given this context, the EU—while implementing Brexit—has been confronted with yet another existential crisis, reinforced and brought forward by the COVID-induced crisis. EU leaders had to decide, in just a few months, whether to give up the project imagined by the block’s founding fathers, or else re-launch it, and so pass it to the next generation of leaders, who would eventually decide its fate.

The decision to react to the coronavirus-induced crisis by launching a comprehensive pan-European plan, based on the EU’s Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF)—significantly dubbed “NextGenerationEU”—signifies that current EU leaders have chosen the latter course: they took the decision to push integration to new levels, in spite of the ongoing implementation issues. Unfortunately, the bad management by the EU on the procurement and distribution of anti-COVID-19 vaccines shows that there is still a lot of work to do to make the EU a more efficient and effective, less bureaucratic operator.

The novelty represented by an anti-European American president during the period 2016-2020 had several implications for the European Union. Donald Trump was not just isolationist and lukewarm regarding the EU integration process, he was openly hostile to it. He was in favor of further exits from the EU. And he was also in favor of diminishing the presence of NATO in the region, announcing a decision to withdraw many of America’s troops from Germany (a decision his successor has frozen). All this had induced even the most prudent politician of her generation, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, to declare that the Europeans are on their own and need to grasp their destiny with their own hands, without relying any longer on the external influence, pressures, and financial and military subsidies from the United States. As we discuss later in this essay, the presence of Joe Biden at the White House will only change this state of affairs at the margins.

In parallel, the way the COVID-19 pandemic hit the EU plainly demonstrated the essential role played by the technology sector in ensuring the continuity of social life, businesses and government activities, and accelerating the need for sovereign digital technologies. Technology ranging from AI and 5G to Cloud computing—the new battlefields for China and the U.S. to assert their global supremacy—has already started to transform every industry, and within a generation will have done so completely.

This new paradigm represents a huge additional threat to each EU member state separately and the Union as a whole; at the same time, it also represents a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for the EU, should it manage to position itself well in the new global chessboard. We will discuss further in this essay the initiatives that have been launched in the field of technology and innovation (as well as financial and capital markets, and defense). The NextGenerationEU plans explicitly requires national recovery and resilience plans to dedicate a large amount of resources to the technological transition.

Completing Economic and Financial Integration

To its critics, the decision by the EU’s founding fathers to begin any form of collaboration from the economic and financial domain is the existential flaw in the entire integration process. In reality, this was a very precise design choice: the generation of the founding fathers still remembered how futile political agreements were in the absence of shared economic interests. The memory of the 1938 Munich Agreement was still vivid in their minds when they decided that the first step of European cooperation had to be centered on the basic economic needs of post-war western European countries: coal and steel. The European Coal and Steel Community (the precursor to all subsequent European Communities) was formally established in 1951 by the Treaty of Paris, signed by Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and West Germany—the “inner six.”

Fast forward a few decades—after the European Economic Community and, eventually, the European Union were created—the principle underlying any further integration process remained the same: rooting any agreement on shared economic interests, because doing so will, eventually, lead to the political union that, for Europhiles, represents the ultimate goal of the process.

The single currency was launched in 1999 and became the EU’s common currency in January 2001. The original design flaws of this project became apparent during the global financial crisis of 2007-2009 and, even more so, upon the onset of the Greek/euro/sovereign crisis of 2010-2012. The lack of resolution and solidarity mechanism beyond the antiquated Growth and Stability Pact meant that the euro was on the verge of collapse in 2012, until European Central Bank president Mario Draghi’s celebrated “whatever it takes” speech in London in July of that year. Since then, the euro-area (a large portion of the EU), has launched a series of communitarian and inter-governmental initiatives that have stabilized the EU’s monetary union and re-launched the economic and financial integration process.

The most notable of the inter-governmental initiatives of that period was the establishment of the Luxembourg-based European Stability Mechanism (ESM), an institution that was endowed with massive financial firepower by the adhering governments in order to stave off any future sovereign debt crisis. It has been allowed to extend loans with stringent conditionality to troubled countries—in that respect, it could be seen as a sort of “European IMF.” The ESM has been tasked with leading the fast-response mechanism during the pandemic through the establishment of a new enhanced credit line, called Pandemic Crisis Support. The ESM is currently undergoing a reform process that will make it more integrated in the official mechanisms and treaties of the European Union.

Among the communitarian responses it is worth citing the launch of the banking union and the Capital Markets Union (CMU). The banking union has three pillars: one, the establishment of a single supervisory authority for large financial institution (this is the so-called Single Supervisory Mechanisms, an independent body within the European Central Bank); two, the establishment of a Single Resolution Fund, to be used in case of distress in the banking system (and which will use the ESM as a backstop); and three, the establishment of an European Deposit Insurance Scheme (EDIS), which will substitute—or at the very least complement—existing national schemes.

The first two steps towards the establishment of an EU banking union have now been completed, and the third is in the process of being discussed—the successful conclusion of this third pillar should not be taken for granted. As any deposit-insurance scheme inevitably entails the use of taxpayer money (sooner or later, directly or indirectly), the stronger, creditor countries, such as Germany and the Netherlands, are trying to slow down the establishment of EDIS until the weaker, debtor countries, such as Italy and Spain, have completed a process of risk reduction.

In the minds of the northern EU countries, this process of risk reduction, in which banks better provide against non-performing loans (NPLs) or reduce their exposure to sovereign debt, must precede that of risk-sharing, considering that taxpayer money is at stake. While debtor countries seem committed to some form of risk control, if not necessarily risk reduction (for example, through the mechanism of the so-called “calendar provisioning” for NPLs), the COVID-induced crisis has largely stopped the de-risking process, which has become unfeasible at a time when all countries face multiple bankruptcies. Recently, it seems that creditor and debtor countries have agreed that the two processes of risk reduction and risk sharing should proceed in parallel. This might allow the EDIS project to advance further, however slowly, in the coming years.

The final step in financial integration (together with the Monetary Union and the Banking Union) is the so-called Capital Markets Union (CMU). This project aims at creating a single capital market framework, for example for the issuance of equities or corporate bonds—the same way the U.S. has done—as an instrument to enable private-sector risk sharing. More intertwined European banks within a CMU—imagine, for example, a Dutch bank based in France, packaging Spanish mortgage loans in products sold mostly to Italians—would make the EU integration process de facto irreversible, like the euro currently is, at least de jure.

Even if it is strategically important, the process towards the creation of a CMU seems to be stalling, partially as a result of Brexit. Prior to Brexit, any CMU project could not be conceived without considering the special role of London as one of the key global financial centers. For this reason, the EU commissioner in charge was British. Now, before making any further progress, it is likely that the EU will have to wait for the eventual outcome of the COVID-induced crisis, which will leave plenty of scars in the continent.

The completion of these three pillars of the EU’s economic and financial integration is considered by Europhiles as prerequisites for the achievement of two additional steps they champion a fiscal union and a political union. In a fiscal union, some or all fiscal resources would be shared. The extreme version of a fiscal union would be a transfer union, in which the “stronger and richer” components of the union would subsidize the “weaker and poorer” ones, at least for a time. Germany’s reluctance to form a fiscal union can be read in part as its fear of it becoming the underwriter of a transfer union.

But some timid steps towards a fiscal union have nevertheless been made. There is now a coordination of the budget process during the annual so-called European Semester, with all EU member states sending their Draft Budgetary Plans (DBPs) to Brussels by every October 15th for comments and revision by the EU Commission. This is part of a larger fiscal surveillance process that the EU undertakes every year—a process that creditor countries consider to be too politicized, and for this reason would like to see it undertaken by a more technocratic body instead, such as the ESM.

In spite of this, the process of a fiscal union seems to be proceeding very slowly. At the EU level, some movement is taking place, however. France has finally managed to introduce a Euro-budget (however small) as part of the regular MFF. It is France’s ambition that this should have some function as a stabilization mechanism and serve as a counter-cyclical stimulus. Germany has agreed to the creation of the fund, as long as it remains endowed with resources in the “low, double-digit figure” of less than €20 billion and remains without a stabilization and counter-cyclical function. The pessimists would say that, with such a limited remit and endowment, this renders it effectively useless. The optimists would say that once the legal entity has been created, scaling it up and enlarging its role (for example to respond to another future crisis) will be much easier.

Finally, the implementation of the NextGenerationEU plan requires the increase of the EU Commission’s so-called “own resources.” These are not just the “membership fees” that each EU member state pays to be “part of the club,” but represent the creation of new EU taxes, levied and managed by directly by the EU Commission, which establishes a supra-national taxing power that so far has been considered an exclusive competence of the member states. These new taxes (on carbon emissions, financial transactions, and digital business) might well constitute the core of any future fiscal union, which might in fact progress top-down (from Brussels to the capitals of the EU member states) rather than bottom-up—or at least run in parallel to one another.

Additionally, another top-down way of pushing for a fiscal union has been enhancing the borrowing abilities of the EU Commission, which will finance the NextGenerationEU plan by issuing its own bonds (which, however, will not enjoy a “joint and several guarantee”), in what some could see an embryonic form of future eurobonds. The re-insurance schemes introduced by the Support to Mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency (SURE) plan (for unemployment) and by the European Investment Bank (EIB) could also be read as a step in the same direction.

Once trade and competition rules, currency, banks, capital markets, and fiscal resources will be integrated, the need for a political union to emerge should come naturally, the architects of the EU would argue. How could these existential decisions—involving several aspects of national sovereignty—be made without a common political authority in place? For the time being, these decisions are made as a result of long negotiations between various EU institutional actors (Council, Commission, Parliament, Eurogroup, etc.) and the national capitals of the member states. In the future, a more federal governance system might emerge, perhaps including the direct election of the EU President.

Military And Security Integration

The question of the European Union’s military and security integration is seen by some as the “new frontier” of what is called the “European project.” Today, the defense of the European continent (and, less broadly, the European Union and its member states) is basically provided by NATO—and in particular by the United States. However, the situation is currently evolving.

In fact, despite U.S. President Donald Trump’ statements on the lack of adequate financing by the Atlantic Alliance’s European member states, the United States does not provide “90 percent” of the NATO budget, but “only” 22 percent. The other two main contributors are Germany (14.7 percent) and France (10.5 percent). In 2020, the United States dedicated 3.5 percent of its GDP to defense ($676 billion), which is equal to two-thirds of the military expenditure of all NATO countries combined, and about one-third of the worldwide total for all military budgets. Recent American increases in defense spending (+$44 billion) were equivalent to Germany’s entire defense budget. Within this budget, American spending specifically dedicated to the defense of Europe is estimated at $35.8 billion in 2018, or 6 percent of the total, which is almost as much as the entire defense budget of France (€35.9 billion in 2019).

The “strategic pivot” to Asia first defined by U.S. President Barack Obama and subsequently pushed forward by his successor represents a permanent change to the European defense paradigm. China is America’s main strategic competitor, and Southeast Asia is the new area of focus. The European continent is not the strategic priority anymore. So far, there is nothing to indicate that the Biden Administration will undertake policies to reverse this change.

At the same time, new threats for the continent have emerged for the EU. Here we can mention two. First, the increasingly interventionist attitude of Russia. It became apparent with the war in Georgia in 2008, then came closer to the borders of the EU with the intervention in eastern Ukraine and the annexation of Crimea in 2014. But the use of Russian force has also been apparent in Syria, with the rescue of Bashar al-Assad’s regime. Such behavior, together with a continuous show of force on EU borders and the use of disinformation, cyber-attack and espionage activities, are reinforcing the conviction of many EU member states that the threat on the EU’s eastern flank remains a reality.

Second, the development of threats on the southern front. EU member states have and are still experiencing a series of jihadist attacks. The onset of civil war in Iraq and Syria, accelerated by the emergence of the caliphate of the Islamic State (IS), generated a considerable flow of migrants towards Europe in general and the EU in particular. Likewise, the collapse of Libya following the Western military intervention has facilitated the establishment of criminal networks. Finally, the weakening of the states in the Sahel-Saharan strip has made that area a base for jihadist networks and organized crime. The situation in the Near and Middle East and in Africa has direct consequences for the security of the EU, its member states, and others countries belonging to the European geography (e.g. the Western Balkan countries, Moldova, Switzerland, Norway, the United Kingdom). From this perspective, the issue of European defense is a short-term practical matter with a concrete impact.

As a result of all these events and factors, EU member states have reached a conclusion that they need to start building their destiny with their own hands from a military and security perspective, without relying too much on the help of their American ally, which has meanwhile become quite unreliable. So, after Brexit, a lot of emphasis has been put on further military and security integration between EU member states. This has progressed along two possible paths: a communitarian approach and inter-governmental agreements.

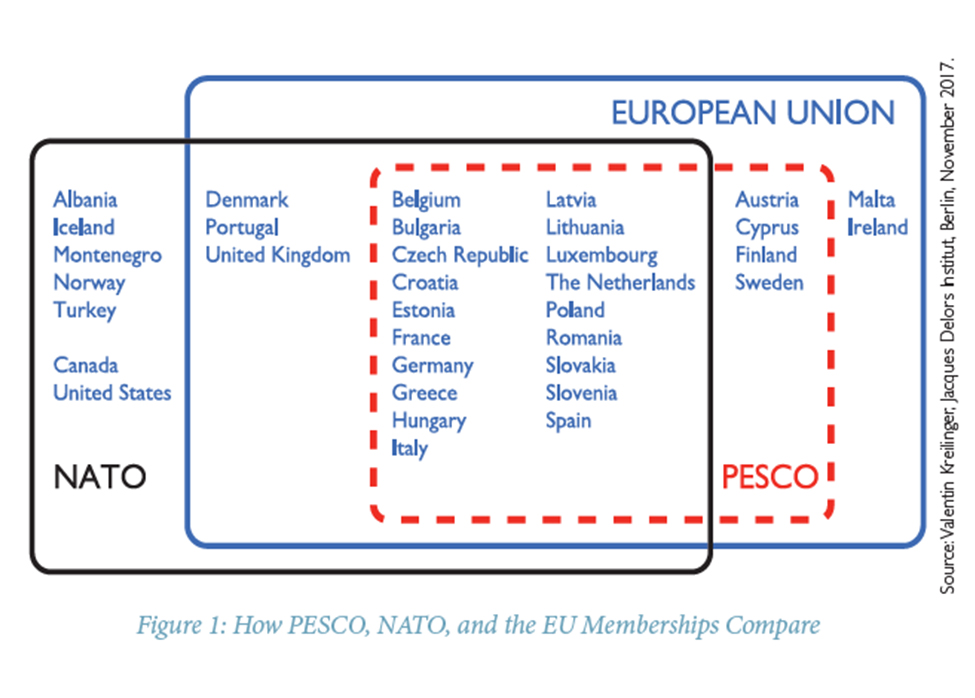

Regarding the communitarian approach, the former EU Vice President and High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Federica Mogherini, launched the EU Global Strategy for Foreign and Security Policy in 2016—the first attempt to redefine the EU’s strategic position since Javier Solana’s plan of 2004. Additionally, a new Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) among EU member states on security and military issues has been launched (see Figure 1), to enhance coordination, increase investment and foster cooperation in developing defense capabilities among EU countries.

Regarding inter-governmental agreements, we can mention that France has offered to share its nuclear umbrella with all EU member states. The future of this proposal will depend crucially on Germany’s position. Meanwhile, Germany has agreed with the Netherlands to effectively create unified commands for some of its military regiments—a clear sign of inter-governmental military integration.

As is typical of the EU, most likely the communitarian and inter-governmental approaches will be pushed forward in parallel, rather than one type of approach outpacing the other.

Technological Transition and Integration

As EU Commissioner Thierry Breton said in September 2020,

Faced with the ‘technological war’ between the United States and China, [the EU] is laying the foundations of its sovereignty for the next 20 years. It is not a question of giving in to the temptation of isolation or withdrawal into oneself, which is contrary to our interests, our values, and our culture. It is a question of making choices that will be decisive for the future of our fellow citizens by developing European technologies and alternatives, without which there can be neither autonomy nor sovereignty. Mobilized around major projects developed in partnership, [the EU] has demonstrated in the past that it has the capacity to play a leading role on the world stage. The time has come to take back the common initiative.

Both the United States and China have key tech “superstar” companies: the FAANG (Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix, Google) in America, also including Microsoft, and the BAT (Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent) in China. There are no equivalent of such big tech companies in the European Union. This is seen as a core weakness, as these tech giants are the basis of innovation in many IT sectors. In order to have leadership in Big Data you need first to canvass those large swaths of data. Cloud computing and the storage and use of such data and applications also requires leadership in Big Tech, something that the United States and China do but the EU does not.

But the European Union is also the world’s number one industrial continent. The EU has every asset needed to win the Big Data race. When it comes to industrial data, the rules of the game are different. Most of the current platforms, mainly built for B2C, are not ready to meet the technical, security, and service requirements required by industry or public authorities. The EU is not lagging behind technologically in the field of industrial data. However, in order to capture the value of the European Union’s industrial market, an EU-level infrastructure has to be built allowing for the storage, use, and creation of data-based applications or Artificial Intelligence services.

In this context the EU Commission plans to launch a European Alliance for Industrial Data and Clouds in order to develop EU alternatives and properly position the EU in the race for the data economy. Such an alliance would be a natural evolution of the Franco-German initiative, the Gaia-X project (France and Germany announced Gaia-X, a federated data infrastructure at the EU level, the objective of which is to build an EU data framework to facilitate data collection, data processing and sharing, especially in the B2B and B2G domains), with a public pillar for common platforms for services of general interest, and a EU industrial alliance around cloud-to-edge platforms.

Another aspect is asserting the EU technology sector’s identity as compared to American and Chinese companies. Despite being the place where global technology leaders were born (such as those of Skype and Spotify), the EU lags behind the United States and China in terms of the number of technology giants it has produced. The EU common market is more fragmented, and capital flows at a different speed in the U.S. or China.

The coronavirus crisis has accelerated some major trends. It has uncovered some of the EU’s overreliance on critical areas—both geopolitically and economically. The EU’s data economy is a pillar of its industrial strategy. Yet what may be the most fundamental difference between the U.S. and Chinese digital spaces (sometimes described as “Technology for Money” or “Technology for Social Control,” respectively), on the one hand, and the EU’s digital space, on the other, may not be capital or market positioning, but rather ethics. One of the key 2019-2024 priorities as defined by the EU Commission is to empower people, rather than just companies or governments, with a new generation of technologies.

The objectives stated by the EU Commission for Europe’s Digital Future is the following:

The digital transition should work for all, putting people first and opening new opportunities for business. Digital solutions are also key to fighting climate change and achieving the green transition. [...] The European Commission is working on a digital transformation that will benefit everyone. Digital solutions that put people first are intended to open up new opportunities for businesses; encourage the development of trustworthy technology; foster an open and democratic society; enable a vibrant and sustainable economy; and help fight climate change and achieve the green transition.

The European Union and its member states have their own history, are attached to human rights, have a more regulated structure than the United States, have a specific political culture, and a specific way citizens live their citizenship including in their interaction with social services. EU institutions are working toward developing a competitive, secure, inclusive and ethical digital economy, which is coherent to its principles, sometimes described as “Technology for Good.”

The next aspect to consider is the EU’s focus on Security. The EU Security Union Strategy for 2020 to 2025, which succeeds the European Agenda on Security (2015-2020), focuses on priority areas in which the EU can bring value to support member states in fostering security for all those living in the Union, notably including cybersecurity.

Among other things, the EU Commission recently completed its review of the Network and Information Systems Directive, proposed ideas for a Joint Cyber Unit, and adopted a new Cybersecurity Strategy. Cybersecurity, together with data control and online platforms’ behavior, represent major concerns at the EU level. Three stand out: first, the overreliance on foreign equipment suppliers for 5G deployment has been identified as a critical weakness; second, the lack of control over data (in a market that is largely dominated by American and Chinese companies), which is subject to extra-territorial laws (such as 2018 U.S. Cloud Act); and third, the dominance of non-EU online platforms is representing a significant threat to EU members’ sovereignty in areas such as taxation, data protection, and copyright.

In this context a number of initiatives have been launched and instruments adopted:

the 2016 Network and Information Security Directive improves EU member states’ cybersecurity capabilities and cooperation, and imposes measures to prevent and report cyberattacks in key sectors (financial markets, banking, energy, transport, etc.);

the 2018 European Cybersecurity Act strengthened the European Agency for Cybersecurity by the grant of a permanent mandate, reinforcing its financial and human resources and enhancing its role in supporting the EU to achieve a common and high-level cybersecurity. It also establishes the first EU-wide cybersecurity certification framework to ensure a common cybersecurity certification approach in the EU internal market and ultimately improve cybersecurity in a broad range of digital products (e.g. the Internet of Things) and services.

the March 2019 approval by EU member states of a EU common toolbox on 5G cybersecurity;

the Digital Europe Programme for the period 2021-2027 is an ambitious €1.9 billion investment scheme into cybersecurity capacity and the wide deployment of cybersecurity infrastructure and tools across the EU for public administration, businesses, and individuals.

cybersecurity is also a part of InvestEU, a general program that brings together many financial instruments and uses public investment to leverage further investment from the private sector. Its Strategic Investment Facility is intended to support strategic “value chains” in cybersecurity and is an important part of the recovery package in response to the coronavirus crisis.

This brings to the fore the issue of private sector leverage. Private initiatives at the EU level are crucial to the development of such an ecosystem. In this context, we can highlight the initiative launched by the European Cyber Security Organisation for the creation of a €1 billion cybersecurity investment platform.

Such initiatives will, if successful, have a significant impact on the ecosystem and, as a result, on the cyber capabilities of the European Union.

Standard-setting

The final issue concerns the importance of setting EU standards, which represents a global business opportunity. Standardization has played a leading role in creating the EU single market. Standards support market-based competition and help ensure the interoperability of complementary products and services. They reduce costs, improve safety, and enhance competition. Due to their role in protecting health, safety, security, and the environment, standards are important to the public. The EU has an active standardization policy that promotes standards as a way to better regulation and enhance the global competitiveness of EU-based industry. All in all, standardization is one of the European Union’s most important soft power tools.

In the digital markets, where non-EU companies have acquired a leading market position, the setting of standards has multiple benefits. Three examples of virtuous standard setting that have become (or are in the process of becoming) global standards rise to the mind.

First, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The EU has adopted a very stringent framework for privacy and data protection, which has introduced a “right to be forgotten” and a “data portability right” to enhance individuals’ control of their own data. The EU is seen as a standard-setter for privacy and data protection, resulting in numerous countries having incorporated GDPR provisions in their national legislation. Some multinationals have also adopted GDPR as their internal global standard.

Second, digital identity. This scheme, launched in 2018 by the EU, enables all its citizens to open a bank account and access e-health records across the Union. The market opportunity deriving from this in terms of authentication and authorization will be worth over €2 billion by 2022, according to the EU’s own estimates. Many countries outside of the EU are adopting the electronic identification and trust services eIDAS scheme in their national legislation.

Third, Artificial Intelligence. The EU has adopted an approach for developing AI technologies that adhere to high ethical standards, with the aim of becoming global leader in promoting responsible and trustworthy AI. In doing so, developers and manufacturers based in the EU will have a competitive advantage, as consumers and users will favor EU-compliant products. Taking leadership on setting global standards in the digital space is certainly (as described above) a global public good that the EU can increasingly provide.

In addition, a plethora of other complementary strategies for ensuring technological leadership has been introduced in the EU. On top of providing global standards in the technological and digital space, the EU can also adopt a wide range of policies that ensure that it will remain a key global player—together with the United States and China—in the technological/digital frontier.

Specifically, combining in a smart way new pan-EU industrial policies, innovative competition policies, more robust and assertive approaches to fair trade and market access, and proper anti-trust actions against non-EU big tech firms that try to monopolize markets, will ensure that the EU remains a key global technological leader.

First of all, as argued by many in the EU, Brussels should change its competition policies to foster the establishment of large, EU-based global players in technology and industry. Some, however, worry about the oligopolistic power of such companies. Certainly, strengthening trade policy to address the unfair trade, investment, technological, and IP practices of foreign powers is a useful approach to take. The consensus seems to be shifting in the EU to the former approach—change competition policy—but one can combine the two—trade policy and competition policies—as they are complementary rather than opposite to each other.

The EU may also need and want to change state aid rules to allow subsidies and the development of EU-wide global champions.

There are some interesting national approaches, like Berlin’s German Industry 4.0 scheme that is aimed at keeping the country’s lead in manufacturing intact, and some pan-EU ones, such as plans hatched in Brussels to develop an European AI ecosystem, the “New Industrial Strategy For Europe,” and the “Digital Single Market” plan.

The EU can also take a more robust approach regarding anti-trust laws, in order to crack down on anti-competitive practices of big tech firms. Finally, some greater degree of cooperation between the EU and the United States under the Biden presidency may be feasible on some matters.

All these approaches can be complementary with each other. For example, in cooperation with EU Commission Vice President Margarethe Vestager, the Commissioner for the Internal Market Thierry Breton is working on a new comprehensive legislative package: the Digital Market Act, which will merge provisions concerning the digital market in the new Digital Services Act, and the New Competition Tool aimed at strengthening competition enforcement. Under the Digital Market Act, the EU Commission will have the necessary legislative resources to fight anti-trust violations, impose new content moderation requirements to online platforms (regarding hate speech, for example), and restrict other anti-competitive behavior.

Implications for the Western Balkans

The EU needs to complete its integration process, but perhaps also its enlargement process with the Western Balkan countries in the forefront. There are at least three main sets of reasons for this. From a geographical standpoint, the proximity of the Western Balkans to EU member states, which surrounded them, make each of them natural candidates for EU membership. From a historical perspective, the inclusion of the Western Balkans in the EU would mean closing (hopefully once and for all) the page that began with the Balkan Wars of 1911-1912 and led to start of World War I. From a geopolitical perspective, integrating the Western Balkans into the EU would mean subtracting them from the growing spheres of influence of Russia and, to a lesser extent, of Turkey. To this we could add a fourth, which speaks to the issue of credibility, namely keeping the promise made way back in June 2003 at the Thessaloniki Summit that the “future of the Balkans is within the European Union.”

The European Union tries to reinvent itself while facing new challenges, and for this reason a Conference on the future of the Union has just been launched. The Conference will likely move from the five scenarios EU Commission president Jean Claude Juncker outlined in the White Paper for EU27 issued in March 2017, which did not consider enlargement as a key element to be taken into account when it comes to envisaging the Union in 2025. At the same time, in his 2017 State of the Union address, Juncker outlined a “roadmap” identifying Serbia and Montenegro as the first two Balkan countries in the EU enlargement priority list for 2025. But other EU officials did not completely rule out the plan to integrate the entire region as a whole.

In this context, it would seem that the Western Balkans are not a top priority for the EU at the present moment; nor are they for NATO, which after the accession of Montenegro in June 2017 is trying to resolve internal disputes fostered by the stance of Podgorica’s new leadership (it seems to have been brought under control). The enlargement of NATO to include a new member state in the Adriatic Sea has toppled Russia’s hopes of having strategic access to the last potential and realistic Mediterranean seaport coveted by the Kremlin.

To sum up, it is well possible that EU enlargement and the integration of the Western Balkans will never take place. If further enlargement fails to materialize, however, the region will continue to serve as a buffer zone and chessboard for major powers. With the EU potentially undertaking no enlargement until 2025, hopes that the region’s countries will intensify their economic cooperation with the European Union during the pre-accession phase remain vague. This is going to make the integration route even bumpier.

Under present conditions, it is likely that the economic interests of the Western Balkan countries in relation to their major economic partners will prevail over pro-EU sentiments in the medium-term. The trade and economic relations of the Western Balkans countries with Russia, Turkey, and China are expected to grow as a result of the increased economic interest of these major countries for the economies of Southeast Europe. In particular, leading with its flagship Belt and Road Initiative, China is making a concerted efforts to increase its influence in the region.

In this context—where the EU remains unable to finish its integration and enlargement process—the role of non-EU international organizations, such as the EBRD, will be crucial in continuing to promote economic and social development in the region, in order to prevent its countries from drifting towards the spheres of influence of Russia, Turkey, or China.

No More Stand-alone

This essay has discussed how EU integration has progressed in the last few years—in spite of Brexit—on various fronts: economic, military/security, and technological.

In the traditional economic and financial field, the completion of the banking union and the implementation of the capital markets union are the key milestones. But short-term crisis solutions might have opened the gate to a much wider-ranging perspective: the bonds that the EU Commission will issue to finance the NextGenerationEU scheme could eventually lead to the establishment of a permanent, pan-EU debt instrument that could serve as the long-awaited eurozone safety asset. At the same time, plenty of skepticism remains in core-eurozone countries around the idea of risk-sharing before any risk reduction has occurred in eurozone-peripheral countries. A case in point is EDIS, without which the banking union cannot be completed.

In the field of defense, the historical retreat of NATO has meant a greater sense of responsibility being taken by the European countries with regards to their own defense. In this respect, the relationship with the UK after leaving the EU will be key, considering that Great Britain is the only European nuclear country besides France. For the EU, it will be crucial to maintain a solid engagement with the UK on defense and security matters. PESCO will be the cornerstone of what we may call the Defense Union, and key next steps will consist of the Coordinated Annual Review on Defence, the launch of the 2021-2027 space budget, and the EU cyber and defense security framework. COVID-19 may have provided the impetus for a coordinated EU response via a dedicated military task force.

In a related field, the EU Commission last year launched its new EU Security Union Strategy for the period from 2020 to 2025, as discussed above. It contains a specific focus on cyber-security. EU partners will have to find a path to rely less on American (and, a fortiori, Chinese) technology, and take increased control over their data. In this respect, the launch of the Gaia-X project for the European cloud represents a breakthrough for the EU to start asserting its digital sovereignty. Data Sovereignty (availability, quality, governance, and security) and AI are central to this new paradigm.

In the tech sphere, the European ecosystem—although unequally distributed across the continent—is increasingly sparkling, with EU tech companies ready to affirm their identity in the global arena. European tech companies have to compete with American and Chinese giants, which have been promoting “Technology for Money” and “Technology for Social Control,” respectively. The EU could attempt to develop an ecosystem aimed instead at fostering “Technology for Good.” The EU Commission has made the digital transformation one of the key priorities for the EU in the next five to seven years. The COVID-19 pandemic may have provided a further boost to this attempt, given the widespread use of digital products during the repeated lockdown episodes.

In short, the EU member states seem to be realising that in the new, post-pandemic world, national and supranational institutions, as well as public and private sector providers of public goods, will all have to work together to make a difference. EU institutions are working toward enabling the emergence of technological leaders on a global scale. There is still a long way ahead, but the direction of travel seems to be the right one. The bottom line is that the scale of investments required, together with the pervasiveness of technology, means that EU member states cannot manage their interests on a stand-alone basis anymore.