Evident, yet so neglected—that would be a proper way to describe the problem of youth unemployment in Southeast Europe. Total unemployment rate in Europe tells only half of the story, because the other half is hiding a painful truth about the incompetence of particular countries to find a place for the brightest minds of their respective societies. North and Western Europe have this issue as well, because even there, many high skilled adults struggle to (quickly) find stable jobs after graduation. However, they are no match for the Western Balkan countries in incompetence, which are not only successful in producing unemployed highly-skilled professionals, but also in exporting them to more developed European countries.

Causes and consequences

Today in Europe, the number of academically educated young people is higher than ever, but somehow, many fresh graduates are staying outside the job market. At the moment, many Southeast European countries are trying to keep their unemployment rates under 20%, (the highest being Greece, which has a 19.1% unemployment rate). But there is the elephant in the room: the percentage of youth unemployment is several times more than the total number of the unemployed persons!

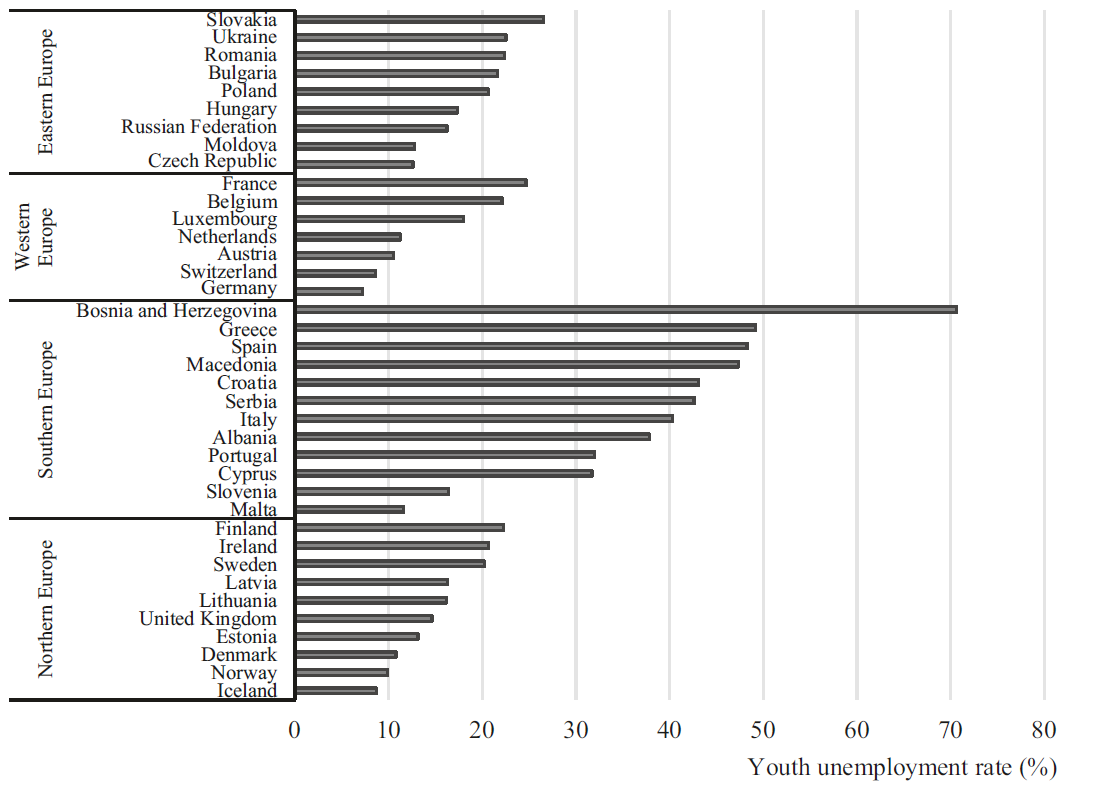

For some regions the situation is very worrisome, because non-EU Western Balkan countries are the undisputed champions when it comes to youth unemployment in Europe (see Figure 1). The situation is even worse because there is no standardized methodology to monitor this issue, and every youth unemployment policy proves to be a total failure due to increasing emigration rates of talented individuals. That is why it is important to gather experience from more developed countries in Europe in order to reach some sort of resolution for this problem.

Figure 1. Youth unemployment rates (15-24) in European countries (Source: ILO Trends Econometrics Models, 2016)

Youth as a metaphor

In fact, even though International Labor Organization and United Nations are selecting population from age 15-24 as “youth,” European statistics prolong this period to the age of 29. There are two reasons for this: first, extended student life due to an inability to leave the family home (also known as “full nest syndrome”); second, the galloping aging of the entire continent. It comes as no surprise that many demographers now refer to the period above the age of 30 as the time when “young” individuals leave their parents’ household.

Unfortunately, is it is expected that future “youth” will come to be classified as a sort of fourth decade adult without having had any opportunity to enter the job market; this is already the reality of many young professionals from Southeast Europe.

Lost generation

The most worrying category is that of young adults who are neither in the education system nor seeking work (sometimes referred to as NEET or the “lost generation”). Very often, these marginalized individuals turn to the grey economy. It is also a problem because these people are often “invisible” to the official labor statistics bureaucrats (they are often hidden under the umbrella term informal sector). For instance, in Serbia, there is a total of 21% of the population that belongs to informal sector of the economy, according to August 2018 data from the National Statistics Office.

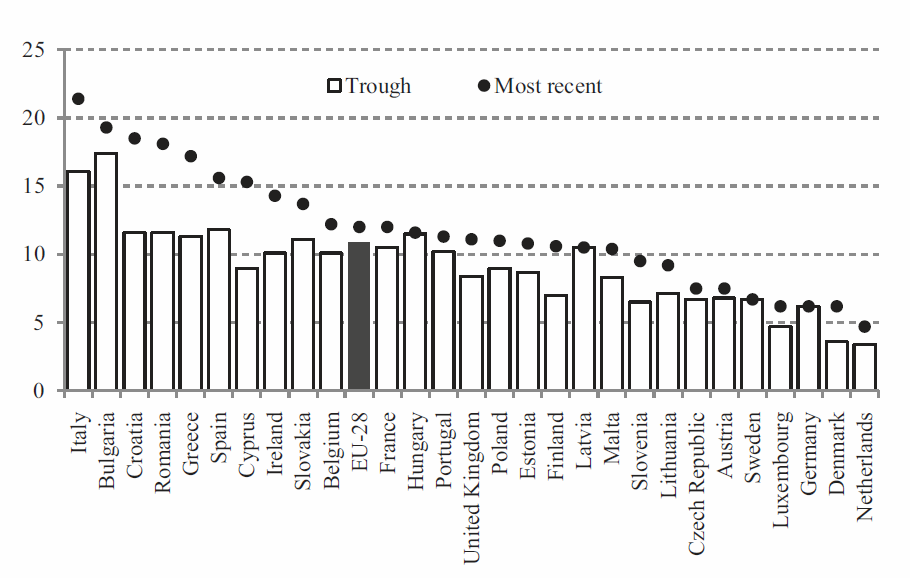

In addition, there is a positive correlation between mental health issues and persons who are unemployed for a longer period of time. The common scenario are problems with alcohol and drug abuse (especially for men). Of course, this puts an additional burden on the (over-) strained health care system of the targeted countries. According to Eurofound, the NEET population costs the European budget over 150 billion euros per year, and for countries such as Italy, Romania, and Bulgaria it is over 2 percent of the GDP (because they have over 20% of NEET generation among the youngest part of their workforce, which also puts them on the top of the most affected countries, Figure 2).

Figure 2. Youth unemployment rates (15-24) in the EU-28 countries (Source: ILO calculations based on Eurostat)

Brain drain

One of the biggest issues for the Southeast European countries is the massive exodus of educated youth into countries that offer much more opportunity for the academic and professional development. Emigration of the most talented individuals is not a new phenomenon, and the EU is also empowering academic mobility within the continent, through, for instance, the Erasmus Programme. But that academic potential is not equally distributed, and some countries (such as Germany, Switzerland, and Austria) are attracting more than one third of the entire research capacity of the Southeast Europe.

According to the German Federal Statistics Office, Germany has absorbed 37.1% of researchers from Spain, as well as an incredible 53% from Greece (that relocated permanently). This shouldn’t be a surprise if the academic salaries are compared: almost 60.000 EUR per year in Germany in comparison to 34.908 EUR in Spain and 25.685 EUR in Greece. In that sense, academic relocation is not choice but a necessity for many talented individuals in Southern Europe.

It is often forgotten that even Germany is being hit by a serious brain drain of medical professionals. More precisely, over 45.000 licensed professionals (with German medical accreditation) are trying to establish themselves in Switzerland and Austria (due to better financial conditions and cultural similarity). But Germany has managed to close this gap with medical immigration from the other parts of Europe. This has largely come at the expense of (Western) Balkan countries, which are simply unable to keep their doctors and nurses from leaving.

Diploma and market, allies or enemies?

In order to reduce youth unemployment, governments need to bring employees and cathedra closer together and create conditions that would be the most beneficial for the lives of young and highly educated people.

One of the potential solutions is to reform admission quotas. Similar policy changes have already taken place in Croatia, with positive results. Since 2011, the University of Zagreb (the largest university in Croatia) has been slowly reducing admissions quotas for many social sciences and liberal arts faculties, while medical and veterinary faculties have had their quotas increased. Some technical department quotas were reduced as well. The government conducted this reform in collaboration with employers. This is a good example for other Western Balkan countries to follow, since Croatia has managed to reduce its youth unemployment rate by 25% in 2018. Even though this type of reform is not a very easy solution, it is definitely a step in the right direction.

In Southern Europe, Spain has also introduced some changes in its system of higher education, because its students are eligible to sign a contract (up to 3 years) that enables them to get practical work experience in companies. Similar measures have existed for many years in Western and Northern Europe (in some states it’s known as Youth Guarantee policy) but its implementation has varied across the Old Continent. In Ireland, for instance, there is a lump sum of 7.500 EUR given to an employer that hires a young person. In Belgium, the government offers employers 1.000-1.100 EUR for a period of 12 months if they hire a person younger than 26 (with maximum secondary education). On the other hand, some EU countries like Italy and Hungary still haven’t taken the planned steps to incorporate education and training for their unemployed youth.

Evidently, the non-EU Western Balkan countries need to take serious steps towards improving the status of their youth labor force. Measures could include transparent monitoring, educational reform, and, most importantly, close collaboration with industry. Young people should not be forced to leave their countries at the beginning of their professional career, but right now it seems this question is not in the focus of the political elites of the Western Balkans.

Author:

Author: