Ramon Blecua is a Spanish diplomat, former EU Ambassador to Iraq, and currently Spain’s Ambassador-at-large for Mediation and Intercultural Dialogue. The opinions in this article are the author’s own and do not represent official policies or the positions of the Ministry. You may follow him on Twitter @BlecuaRamon. Douglas A. Ollivant is a Senior Fellow at New America. He is Managing Partner at Mantid International, a global strategic consulting firm. A retired U.S. Army officer (Lieutenant Colonel), his last assignment in government was as Director for Iraq at the National Security Council during both the Bush and Obama administrations. You may follow him on Twitter @DouglasOllivant.

Regardless of who leads America in the next elections—and next decades, for that matter—the geopolitical environment in which the United States will operate will be significantly if not fundamentally different from that of the last century. In particular, the world stage will be more “crowded” with actors of all sizes and flavors. This is a challenge with which no major state seems to have wrestled effectively, but the United States perhaps least of all.

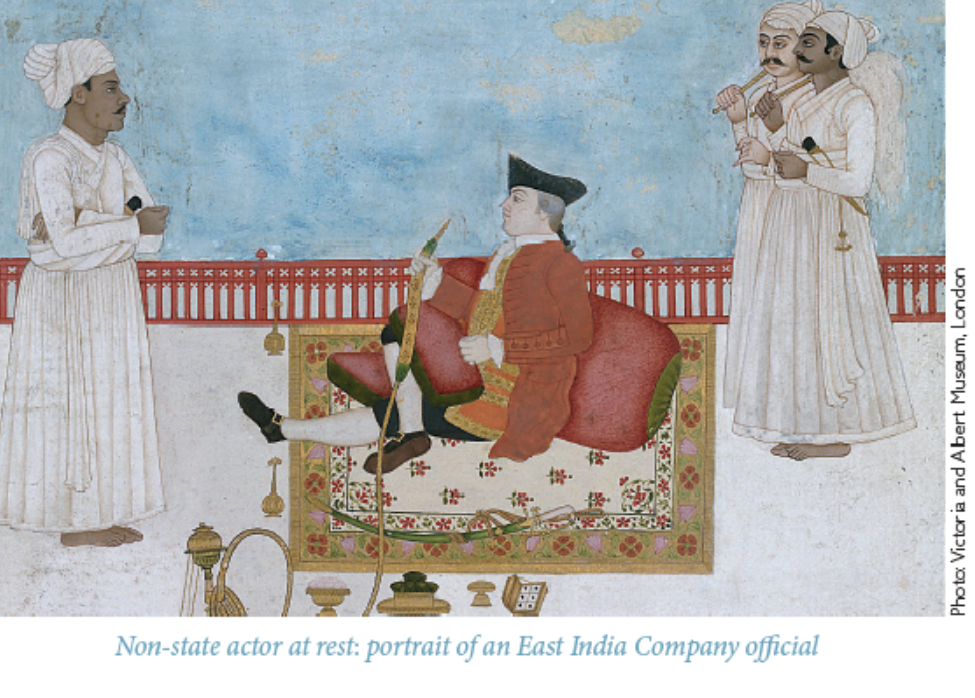

While the Treaty of Westphalia may not be the seminal moment often attributed to it, the “Westphalian” system it created has nonetheless been the default for some centuries. In this system, states are the primary actor and non-state actors can only hope for a secondary role. While exceptions to this rule have always existed (the British East India Company, the Rothchild Banking house, and the Jesuits come to mind), it was nonetheless the normal, default framework. However, the nature of the international system appears to be in flux and a rearrangement of power relations is taking place. Sub-state actors are using new pathways to power and while they may not be able to challenge the most powerful nation states in their core interests, they can do so more effectively on the periphery, and against weaker states with even greater impunity.

The first systematic notice of this near reality was probably by two Chinese colonels named Qiao Liang and Wang Xiangsui in their controversial 1999 book Unrestricted Warfare who identified—by name—George Soros (for his attacks on Asian currencies in the late 1990s), Osama bin Laden (still pre-9/11), Pablo Escobar, Chizuo Matsumoto (the founder of the Aum Shinrikyo

movement) and Kevin Mittnick (a prominent 1990s hacker). While none of these individuals would still be noted, or at least not for these activities, the categories they represent—financial power, religious terrorism, organized crime, and data technology—seem quite prescient, if not quite complete.

A short list of today’s major non-state actors has different names, but similar categories. Hezbollah, ISIS, and Al Qaeda remain major players as terrorist actors. However, the power of individual hackers has now been eclipsed by major tech firms—Google, Facebook, Amazon, Apple—to name the most obvious. The cartels and other organized crime groups remain notable at least in their own spheres. Steve Coll has made a powerful case that Exxon should be considered a “private empire” in his book of the same name. Similarly, major financial firms—Goldman-Sachs, KKR, Black Rock, Deutsche Bank, Merrill Lynch—wield power in ways both subtle and not. It is interesting that the Unrestricted Warfare authors did not see in the early private security firms—Executive Outcomes and SandLine—the eventual emergence of both BlackWater and their Russian counterparts—the Wagner and Moran Groups. Finally, private NGOs such as Open Society (bringing Soros back into the picture in a very different capacity), Human Right Watch, and the Gates Foundation are global players that influence the international agenda in significant ways.

Not Always in Synch

Non-state actors traditionally have been considered an anomaly or a disturbance to the existing international order. In the Middle East, the term is mostly applied to define terrorist groups or militias that are considered a threat to regional stability, operating at the behest of different patrons in their confrontations through proxy. Nevertheless, we are dealing with a more complex phenomenon that is redefining power struggles in and beyond the region. The influence of powerful non-state actors is becoming more relevant at shaping state policy than the classic power competition among states, while getting intertwined with it in subtle ways.

The Middle East is a special case within this global process, since its dysfunctional financial systems and lack of IT champions makes for a limited array of local players on the field, opening the game for more external influences. In analyzing the long term trends at play we have to match the different dynamics operating at the international stage and the regional arena and they don’t always go in synch. The impact of social media in consolidating the recent protests movements in the region has been a surprise to the traditional elites of the states affected, sparking accusations of foreign interference and destabilization operations.

The main players remain the warring states in conflict, be it Saudi Arabia using digital platforms to promote its new role, the UAE hiring Israeli tech companies for intelligence gathering, or Iran using its “electronic army” to wage war in the internet. Nevertheless, the new forms of warfare are changing regional dynamics and bringing the IT platforms to the forefront of regional conflicts as parties. The closing of Iranian accounts in different social media and the American decision to ban Chinese companies access to certain technology is an example of how the strategic impact of AI and social media will affect the neutrality of the internet and the Big Tech companies.

The real game changer is that states are not anymore the only protagonist and they have to accommodate the increased power and influence of transnational corporations—of which Big Tech is the ultimate example—private military forces and militias, transnational terrorist organizations, and the staggering wealth of criminal groups and drug cartels. The privatization of surveillance technology and military services is probably the clearest symptom that even global powers such as the United States or Russia, or regional ones such as the UAE or Saudi Arabia, need to rely on these private corporations to conduct warfare and that is changing the nature of international relations. The use of military alternatives, instead of diplomatic initiatives, has become easier and more acceptable politically for governments, but also wealthy individuals or corporations could eventually hire a private army for their own reasons, particularly in weak or failed states.

New Kids on the Block

The most novel players in this new world are technology and social media firms. These firms specialize in surveillance—whether voluntary or involuntary. Firms such as Facebook, Google, and LinkedIn use voluntary surveillance—living on the data that users voluntarily allow them to access, or arguably own. However, as demonstrated on numerous occasions, this data can also be used to manipulate users into believing data that is skewed or simply false. When used for marketing, such manipulation is deeply troubling, but also when used to manipulate political data and elections, it is truly terrifying.

On the other end of the technology spectrum are firms that use only involuntary surveillance—using data without the user’s knowledge, whether that data is public or private, and can be accessed legally or illegally. The exemplar of these firms is the UAE’s Dark Matter. While it has a very close connection to the Emirati government, it is still at least nominally independent (an arrangement that will often be seen). Dark Matter was used to track and manipulate perceived enemies of the Emirates—whether foreign operatives and terrorists, or domestic dissidents.

But any “big data” system can be used for predictive analytics to surface behavior, given the proper data inputs. Even without hacking, the consolidated picture from correlated publicly traded data can give insights that would often disturb the individuals involved. Stories about marketers knowing women are pregnant long before they tell their families are quite rampant, and the impact of the COVID-19 tracking of personal data is another example of the potential of these surveillance technologies. This scenario will be significantly amplified by the expansion of 5G-related sensor-fed real-time flows and smart cities operating on huge data collection systems.

Next are the mercenary companies. While mercenaries have been defined as the “second oldest profession,” the latest iteration of Western mercenaries can be traced from the “Wild Geese” of the 1960s, to the more professionalized Executive Outcomes and Sandline of the 1990s, and culminating in the Blackwater, Triple Canopy, and Olive Group of the Iraq and Afghanistan war eras. Meanwhile, on the Russian side, firms such as Wagner Group and Moran Group emerged at the intersection of GRU and Spetznatz veterans and Russian oligarchs, with strong connections to the Russian state from both groups. A third variant has emerged in the Middle East, with the UAE hiring Commonwealth officers for South American soldiers to execute Emirati interests.

To date, these groups have primarily served as auxiliary forces for states, and are therefore largely within the state system. However, the potential for these forces to begin to work outside the system—working for high-net-worth individuals, NGOs, crime syndicates, or other forces—is very present.

However (again to date), the impact of these companies has been relatively marginal, since they are no match for the high-tech armies of the Twenty-first

century. While Wagner Group was certainly involved in the Russian de facto annexation of portions of Ukraine and Georgia, working in areas primarily populated by Russian co-ethnics does not present a high degree of difficulty. When Wagner’s cadres went against a first-tier opponent at the 2018 Battle of Khasham in Syria, their force of hundreds was destroyed in detail by a small continent of U.S. commandoes controlling U.S. airpower. The recent debacle in Venezuela by Silvercorps, much like the failure of South American mercenaries in Yemen engaged by Academy on behalf of the UAE, demonstrates the real limitations of private outfits providing military services. Nevertheless, this situation could change if these organizations get access to AI and big data, or if they operated in association with tech firms.

The success of technology firms, which has propelled them to center stage because of their global influence in shaping information flows and public opinion, stands in contrast with the limited performance of private military outfits. To date, however, all these efforts have been in the service of nation-states or their leaders. Examples include the Saudis infecting Jeff Bezos’s phone or monitoring the movements of Jamal Khashoggi. The Russians have been caught manipulating Facebook to manipulate U.S. voters, and using YouTube to disseminate propaganda from Russia Today.

Until now we have seen a mutually beneficial relationship between certain states and these new players in the international arena, but it is not unthinkable that in the near future that relationship will be inverted. Big Tech will actually have more control over personal data than individual states and they will be the ones providing essential surveillance services, public opinion influencing, and social control instruments.

Back to the Future

The Middle East has been in turmoil since 2011 as a result of uprisings that rocked existing political structures in the Arab world. The series of events that followed are much deeper than a change of political elites or replacement of authoritarian rulers, but rather, a systemic crisis that has shaken the foundations of the region order and the legitimacy of state institutions.

The situation in the Middle East offers a particularly stark example of how this crisis can accelerate a process of authority fragmentation, institutional collapse, mismanagement, rampant corruption, and failed governance. Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Libya, or Yemen already can be considered test cases of this neo-medieval model of fragmented authorities and overlapping loyalties, in which non-state actors are already the main decisionmakers. A narrative of proxy wars between Iranian-supported revolutionary movements and states aligned with the United States and Western powers may be convenient for media purposes, but it certainly does not explain what is happening in the region or how to address the many fault-lines at play. We may be soon facing a scenario in which whoever prevails militarily will be relatively irrelevant in the face the chaos provoked by the meltdown of the regional state system and correspondent security architecture.

The context in which non-state actors are operating is defined by the demise of the social contract between the citizens and the state as a result of complex socio-economic changes. The failure of the economic systems in most Arab countries to offer jobs and services to bulging populations with uncontrollable demographic growth fuels discontent that is changing political dynamics. The other factor that limits a state’s ability to react to those challenges is the sclerosis of political systems based on authoritarian models. The diminishing legitimacy of those regimes is being challenged whilst state institutions are eroding.

The economic model of Arab socialism may be bankrupt but it remains in place as a parasitic structure being used by predatory elites to divert resources from the state into their own hands. Non-state actors are claiming the space left vacant in the political, security, and social arenas, creating parallel structures and organizations that can claim more effectiveness than the state. The growing power of tribal, sectarian, and ideologically inspired groups is changing the inner workings of the existing political systems, even if those groups still don’t openly advocate for their removal. The increasing influence of tribal warlords and ideologically-motivated militias from Libya to Yemen will shape regional dynamics for a long time to come. The reason why these groups do not replace the dysfunctional institutions by other political structures is, obviously, the enormous economic benefits that they can extract from them.

In 1994, Robert Kaplan published in The Atlantic his famous essay “The Coming Anarchy” in which he used the example of West Africa to describe the future scenario that would confront our deceptive sense of security. Disease, overpopulation, unprovoked crime, scarcity of resources, refugee migrations, the increasing erosion of nation-states and international borders, together with the empowerment of private armies, security firms, and international drug cartels would in a few decades confront our civilization. Twenty years later, in a galaxy not that far away, a splinter group of the famous Al Qaeda transnational terrorist franchise took control over a third of the territory of one of the most powerful countries of the Middle East in a matter of weeks. The Islamic State—or Da’esh as is widely known in the region—seemed to respond to Kaplan’s prophecies with apocalyptic precision, reaching the gates of Baghdad while the Iraqi army floundered without a fight and the state was on the brink of collapse.

The demise of national states predicted by Kaplan may not have taken place yet, but the dynamics of war have changed and private armies, tribal militias, non-state armed forces, and transnational terrorist groups tend to decide the outcome of conflicts in the region much more than national armies.

The survival of the Syrian regime, the resilience of the Houthi movement in Yemen, and the comeback of the Iraqi state from the brink of collapse holds many important lessons to understand the rules of the new game that will serve as a basis of the future security architecture of the Middle East. Lebanese Hezbollah surprised the world by inflicting the first tactical defeat to the Israeli army in 2007 and Ansar Allah rebels prevailed in the ongoing war against the Saudi-led coalition since 2015.

The strategic parameters in regional security need to be adapted accordingly, but such paradigmatic transformations are not easy to digest. Da’esh represents the most evolved version of a non-state actor capable of replacing the whole state system with an alternative hybrid organization, using IT instruments massively and strategically as never before seen in the Middle East. The initial reaction that turned the tide and saved the Iraqi state came also from non-state actors: the highest religious authority in Najaf and the Popular Mobilization Forces, demonstrating a surge of equally potent energy and resolve.

One would not exaggerate to say that Hezbollah and Al Qaeda are among the most prominent examples of non-state actors in the region. Despite their common loathing of Western imperialism and Israel, Hezbollah and Al Qaeda (or its offshoot Da’esh) have a deep hatred for each other and are pitched in an existential battle that is rooted in secular sectarian differences. From Syria to Iraq or Yemen, the main mobilizing factors of the Shia communities—more than external intervention—has been the threat from what they denominate the takfiri jihadi groups, inspired in a hostile extremist interpretation of Sunni Islam.

In all of those scenarios, Hezbollah has become the model organization and training provider for local militias, with the strategic and financial support of Iran. Lebanon was the first country in the region where Iran established a foothold, as champion of the neglected Shia population, shortly after the Israeli invasion in 1982. The establishment of Hezbollah, as a political and military organization, inspired, organized, and funded by Iran’s Revolutionary Guard, has been one of Tehran’s most far-reaching initiatives. The unique characteristics of Hezbollah as an armed group have evolved from the extreme violence of the early beginnings (using suicide attacks, assassinations, and hostage takings), into an extremely sophisticated and effective military force.

The expansion of Da’esh from the countries of West Africa to Southeast Asia should not be taken lightly, since a new Da’esh 2.0 could be more deadly than its predecessor. The military victory over the Da’esh Caliphate is certainly significant, but it remains a force to be reckoned with, both in Iraq and Syria. We should not forget that it took an unprecedented international coalition with over 50 countries and the full weight of the American military to defeat a force of 30,000 fighters with a cottage military industry of their own.

The current escalation of tensions between Iran and the United States is offering it the breathing space to reorganize and plan a comeback in the areas it once ruled, while Washington’s attention has shifted to the next conflict. The complex interaction between Al Qaeda and Da’esh remains to be defined and could be subjected to new and more deadly mutations.

The United States has taken notice of the geopolitical relevance of many of these non-state actors beyond their national environment for decades and kept defining different strategies to deal with them. The latest version is implementing a strategy of cordoning them off and strangling them economically or targeting their leaders and military forces as part of Trump’s “maximum pressure” campaign against Iran. This strategy is directly linked to rolling back Iran’s regional influence and views the aforementioned groups as Iranian proxies that act as part of their regional grand design.

There are certainly arguments to support such a perception, but it is also a dangerous simplification that could also lead to counterproductive decisions. Aside from creating massive collateral damage, by lumping together many different actors with diverging interests and objectives, this strategy will multiply regional instability and increase the reliance of many of these actors on Iranian support.

A careful assessment of the local context and the interests of the different players could yield considerably better results as well as contribute to regional security and allow for more effective state building. Looking at Yemen, Syria, and Iraq can provide useful case studies to illustrate how the new regional and global dynamics intersect and how conflict resolution and crisis management will have to evolve.

The Yemen Wars

Yemen has been often overlooked as a sideshow in the power struggles of the region, even when the fate of powerful players has been undone in its dramatic mountain landscape, as the Egyptian army still bitterly remembers. After six years of an inconclusive war in Yemen between a Saudi-led coalition, supported by the U.S., UK, and France, and a tribal militia still named after the clan that leads the group, pundits are struggling to understand how that will affect regional security. The wars within wars in the country, which are the result of the collapse of the Yemeni state, will act as a magnet of regional tensions for years to come and will haunt neighboring countries with unknown dangers.

Southern Yemen is fraught with internal conflicts in which Houthi allies, pro-independence STC, Islah supporters of President Hadi, AQAP, and Da’esh will fight with the encouragement of foreign powers. On the other hand, a possible arrangement based on tribal conflict resolution mechanisms would offer a model of how to address a complex conflict with geopolitical implications through locally rooted solutions. Recent announcements of a cease fire by Saudi Arabia may indicate there is a chance of some sort of deal, but the conditions outlined by Ansar Allah as the basis for an agreement seem difficult for Riyadh to accept, at least for the moment.

The strongest player emerging from this mayhem is Ansar Allah, a movement with deep roots in Yemeni history, although the Iranian revolution had an important effect on its mobilization and military organization. Articulated around the al-Houthi, an extended clan that is at the center of a network of alliances between influential tribal sheikhs and prominent Hashemite families, the organization has evolved from an organic alliance of multifarious elements in a tribal environment into an effective military and political structure bonded together by loyalty to their leader and by social, religious and tribal relationships.

President Ali Abdullah Saleh himself was victim of the group he helped raise to power after his ousting, when both the Saudis and his former associates sacrificed him to popular anger. He had launched a series of bloody campaigns against the Houthi and their tribal allies, with the support of the United States and Saudi Arabia, accusing the group of being a threat to both the state’s republican nature and regional security. Iranian support at this stage seems to have been limited and mainly consisted of training through Hezbollah and some small-arms deliveries—something that has significantly changed in the course of the ongoing war. Now, advance electronic warfare, drones, and missiles supplied by Iran are being used to counter Saudi and Emirati superiority in military hardware.

When the forces led by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates launched their Decisive Storm campaign in March 2015, it was widely believed that modern weaponry and unlimited resources would prevail over a tribal militia. Instead, Ansar Allah’s forces are now operating 140 km inside Saudi territory, launching regular missile attacks against Riyadh and military bases of the coalition, and taking the offensive in al Jawf and Maareb against the internationally recognized government’s forces. Despite the essential Iranian support for missile technology and use of drones, Houthi strategy and military operations are not under Teheran’s control. That being said, the Houthi did assume responsibility for the combined missile and drone attack on Saudi oil facilities last June, an operation that was widely assumed to be beyond their capacity.

The current negotiations brokered by the United Nations between the internationally recognized government and Ansar Allah have been dragging on since the war started in 2015 with very limited results. Despite the fiction of this being a negotiation between the legitimate government and the rebels, it is well known that the resolution of the main conflict will depend on the negotiations between Saudi Arabia and Ansar Allah. This is a good example of how a supposed non-state actor has foreign policy and geopolitical decisionmaking, territorial authority, and undisputed control over the military forces in it. The outcome of these interlinked conflicts is still unclear, but the forgone conclusion is that the Yemeni state, or what may remain of it, will never be the same.

Syria and the Battle of the Seven Kingdoms

The confluence of internal conflicts and regional fault-lines makes the Syrian conflict an inspiration for the dystopian Game of Thrones blockbuster series. If we want to find an example of war by proxy, the Syrian case offers us the richest research material. the United States, Iran, Turkey, Israel, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, France, Russia, Iraq, and Egypt have all played a part in one of the bloodiest wars in recent history.

Most of the Syrian actors have one or more foreign patrons that exercise varying degrees of influence. Militias, transnational terrorist organizations, and private armies have graduated as influential actors in the Syrian battlefronts. Wagner and Moran as contractors for the Russian military, PKK-affiliated YPG Kurdish militias, Iraqi PMF, Al Qaeda avatars Jabat al Nusra or ISIL, and the different Turkish affiliated groups are now operating beyond the regional stage.

After nine years of one of the bloodiest conflicts in the region, the Syrian government has prevailed militarily, in an uneasy alliance with the SDF forces, while what remained of the opposition groups was taken over by Turkey and kept in a relatively protected reservation in Idlib. The situation in the northeast remains very fluid since the threatened withdrawal of American forces and the autonomous administration run by the YPG is still in place under the theoretical authority of Damascus. The Russian-Turkish agreement has offered temporary reprieve from a full scale war, but a PKK-controlled enclave next to the Turkish border is a flashpoint that could erupt any time.

In the meantime, a negotiating table of the main foreign players has not just legitimized foreign meddling in a communal war but elevated the interests of the foreign parties over those of local actors, of which they become “representatives” at the negotiation table. All recent initiatives involving primarily local actors failed since they fatally ignored the interests of powerful external backers. External actors do not see any immediate risk for themselves in perpetuating the proxy war and much of the “conflict management” was about taking care of those interests that did not conflict with those of the other Astana Group’s members.

The current fallout between Moscow and Ankara over Idlib, like the simmering war between the SDF and Turkey in Syria’s northeast, is nothing other than the inevitable violent resolution of the ambiguities that previous negotiations had left unresolved. Inevitably, their resolution is going to be reached militarily, with the only difference being that this time, at least one of the three Astana Group’s members—most likely Turkey—will have to accept a zero-sum solution to its disadvantage. The Syrian government may have claimed victory, as the last man standing, but such a pyrrhic victory is not the end of the war, which now seems to be moving to the economic warfare stage that the United States has already declared, supported by the EU’s stringent sanctions on Damascus.

The winning partners of the Assad regime—namely Russia and Iran—have no financial resources to support infrastructure reconstruction or economic reactivation. The territorial control of the regime is tenuous and different local militias remain the real authority in large parts of the country, just as the YPG remains in control of the Kurdish areas. Iran and Russia finance their proxies directly without going through the Syrian Government, and thus exert real control over military operations. This means that Assad finds himself in the uncomfortable position of being a vassal sovereign in a land ruled by armed bands of uncertain allegiances.

Warlords and the Iraqi State

It is in Iraq where the strategic balance of the region will be decided. This is but one reason why the term “proxy competition” between Iran and the United States and its allies is being used more frequently these days. Recent bouts of escalation also illustrate how the narrative of proxy warfare can misdiagnose the nature of the threat and help escalate a geopolitical standoff based on what are in reality local actors’ strategic positionings and machinations. What gets lost in this narrative of proxy warfare in the Iraqi context is the extent to which foreign interests actually prevail over the parochial interests of the actors on the ground. It is undeniable that many groups have close ties to outside powers since the fall of the Ba’ath regime or even prior. However, under closer scrutiny, it is unclear whether these partner or support relationships can accurately be described as “proxies.”

In December 2017 Prime Minister Hayder al Abadi declared victory over Da’esh, after all of Iraq’s territory had been liberated from the scourge of a murderous terrorist organization. The wave of optimism that made Iraq one of the rare success stories in the region did not last for long. The elections that followed delivered inconclusive results that made it particularly difficult to form a stable government and made those parties that command a military organization the arbiters of the situation. Warlords of different shades became the kingpins of the new Iraq, leading to the decline of the Dawa party as the main powerbroker. Not only Sairoon and the Fatah coalition but also the main Kurdish parties, KDP and PUK, have military forces that respond to their respective leaderships.

Fractured authorities and overlapping loyalties have plagued the reconstruction of the Iraqi state since 2003, when the monopoly of force was divided between a weak central government, the United States military, a variety of private American contractors, and multiple militias and armed groups (including the notorious AQIM under Abu Musab al-Zarqawi). It is also misleading to single out the PMU as the main actor undermining state authority, since tribal and religious groups also have an increasingly influential role. The Hawza of Najaf are a center of power accumulating tremendous political and economic power and unparallel social influence even beyond Iraq’s borders.

Iraq lacks a powerful private sector, with economic resources being dependent on political influence and connections. The pledges for economic reform have been repeatedly blocked by the interests of the political elite in keeping the system established in 2003 unchanged, and even the protests that rocked the state and brought the government down are being slowly dragged to a halt.

Iran and other external players took the opportunity to promote their own allies and support their military forces in a struggle for power defined by shifting alliances and conflicting loyalties. We can take as an example the conflict between Maliki and Sadr: on the one hand, it has remained unchanged since 2007 until now; on the other hand, the conflict’s external sponsors (mainly the United States and Iran) kept changing sides. The fact that Iraq is a rich country with large oil income makes the traditional proxy-patron relationship not applicable, since control of the state institutions yields much more than any external contribution. This explains why the relationship between Iraqi actors and their foreign sponsors is much more dialectic than in other cases and reflects the changing circumstances of local, regional, and international politics.

The PMU is a state-sanctioned body that presents itself as an upholder of the state and Iraqi sovereignty and its relationship with other state institutions and political actors is one of bargaining, collusion, and competition. The Fatah coalition, formed by Iran-leaning elements of the PMU, was among the primary sponsors of the outgoing government of Adil Abdul-Mahdi in October 2018. The PMU’s normalization and institutionalization have accentuated its role as defender of the status quo. At the same time, a power struggle has been taking place among the different factions and the main architect of the organization, Abu Mahdi el Mohandes, concerning its structure and role. With his assassination in early January 2020 by the United States, the field was left open for the warlords to consolidate their power. Iraq is in a state of political flux, with political control and power very much up for grabs. With rising political power and influence, the domestic and national interests of the Iraqi actors have sharpened, closely linked to their stakes in the economic benefits that their political clout have brought.

The recent wave of popular protests that started in October 2019 may be a symptom that the “mohasasa taifa” has reached the end of its rope. Disaffection of Iraqi society at large with a system associated with corruption and inefficiency will make a shift inevitable once the main political actors stat fighting over the spoils. Some of the leaders of the PMF allied to Iran were quick to point at a destabilization campaign through massive manipulation of social media from hostile foreign powers (i.e. the United States and its regional allies).

It is quite interesting that many of the state institutions remained on the sidelines of the fight between protestors and different armed groups, both outside and inside the state security apparatus. After months of a stand-off between the different players, a new government headed by Mustafa al Khademi has been approved by Parliament. His mandate is limited and his political support shaky, but the new prime minister has taken some bold and clear decisions to regain the initiative and send a message of change to the Iraqi society in the face of rather daunting challenges. The catastrophic economic situation, considerably aggravated by the recent crash in oil prices, appears to have triggered a fight among the different warlords for a larger share of a smaller pie or further social unrest. Iraq may still walk away from the brink and surprise the forecasts of its demise once more.

The Integration Challenge

The traditional approach to policymaking and regional security does not work in the way it used to in the dynamic and unstable situation of the Middle East today. Inter-governmental organizations—be they the Arab League, the GCC, or the Middle East Strategic Alliance—have become completely sidelined in the management of regional crisis. On the other hand, non-state actors cannot be simply dismissed as temporary anomalies or dangerous spoilers that impede effective governance. Many of these groups just occupy the void left by dysfunctional state institutions and predatory political elites. Their capacity to mobilize support among local constituencies gives them some sort of legitimacy and their control over the use of force in a certain territory provides a quasi-state character to them.

That being said, there are important differences between organizations that receive their authority from centuries-old tribal traditions or religious authority and terrorist groups or criminal organizations. Yet, the boundaries are often blurred in the conflicting political landscape and shifting alliances of the Middle East, which makes it difficult to design a “one size fits all” methodological approach.

Some of these actors do have as their main objective the destruction of the existing political system—whether for ideological or other reasons. They seek to impose an arbitrary and violent rule by force of arms in the revolutionary manner that has animated twentieth century politics. Nevertheless, many of the groups that have been raised to positions of influence as a result of internal conflicts or political crises, aspire to be coopted into the state; and doing so may have as a benefit bringing in renewed energy and social support. What is clear is that we need a new approach to non-state actors and conflict resolution in the region, accepting that the new realities emerging from the past decade of turmoil require also different analytical tools.

What we are witnessing is a transformation of the traditional state into what is now defined as a “hybrid state” in which there is no monopoly of force and security structures. Decisionmaking is channeled through state institutions but made elsewhere by actors outside the formal legal system. State institutions remain in place but the operating system has been modified to accommodate the interests of those influential players that prefer to remain in the shadows. When trying to understand hybrid actors operating in hybrid states like the PMU in Iraq, it is unhelpful to think in terms of rigid binaries between state and non-state, formal and informal, and legal and illicit.

Armed militias, terrorist groups, and criminal organizations thrive in the grey areas of the war economy—a result of the combination of sanctions, armed conflict, and state controlled economies that have plagued the Middle East for years. Economic sanctions have always existed, either in the primitive form of military blockades or in a more sophisticated way using financial controls and economic instruments. Nevertheless, they had not been used in such a widespread manner until about 30 years ago—theoretically to avoid the use of military force to achieve behavioral change of states, groups, or individuals. The truth is that sanctions have had the most paradoxical result of reinforcing the power of those that can operate outside the legal economic system—and often there happen to be the same groups or individuals they are supposed to punish.

The best example of the use of incentives of illegal economic activities to finance a political project is that of ISIL, with a ruthlessly effective organization that plundered and traded all the resources at its disposal: using existing sanction-evading networks to create new profitable partnerships. Another tragic example of the effects of a war economy is Yemen, where a whole network of economic interests and partnerships across conflict lines have been created—to the benefit of politically connected actors that continue to fuel the conflict to their own benefit. In Syria, conflict has paved the way for new groups and elites to control territory and generate revenues. In Yemen and Libya, armed groups have been able to capture state resources and infrastructure, developing lucrative revenue streams. In Iraq, the grey area between groups that are nominally affiliated with the state and a well-established shadow economy continues to shape political developments.

In short, a thorough mapping of the extent of the connections between politics and shadowy economic systems is critical for effective conflict resolution.

More than 80 percent of conflicts over the past 30 years have involved pro-government militias while the more recent rise of transnational violent extremist groups has prompted an even greater reliance on these groups. These forces have played crucial roles in helping governments win back territory, weaken rebel forces, and consolidate battlefield strength. At the same time, they have also exploited conflict situations for their own economic and political gain. Moreover, they may become spoilers to any peace process that would curtail those benefits, especially where they are excluded in political talks and integration deals. In this environment, mediation and track 2 diplomatic initiatives will become increasingly relevant tools for conflict resolution.

It is clear that we need a fresh approach to how these organizations become actual stakeholders in the increasingly common hybrid states, becoming the most relevant decisionmakers not just in security matters but in economic operations and, indeed, foreign policy as well. In fact, non-state actors are the ones that frequently make the decisions that are then simply implemented by state institutions.

In the polyarchic world we are living in, the whole picture is only complete when we integrate non-state actors into the game. Admittedly, it is a difficult task to determine when, how, and who is to be considered an acceptable non-state actor, versus one that is a disruptive force that can only have a malign influence on the system. Nevertheless, crisis management and conflict resolution cannot be addressed effectively without finding new models that include those actors.

Adaptations must come regardless of what direction the United States takes in the coming years. While sub-state actors are nothing new, their recent emergence comes after a long period of state supremacy. Navigating a world in which these forces play a more prominent role may be the true crossroads of world engagement.