Andreas Theophanous, a Professor of Economics and Public Policy, is Head of the Department of Politics and Governance and President of the Cyprus Center for European and International Affairs at the University of Nicosia. You may follow him on Twitter @AnTheophanous.

Andreas Theophanous, a Professor of Economics and Public Policy, is Head of the Department of Politics and Governance and President of the Cyprus Center for European and International Affairs at the University of Nicosia. You may follow him on Twitter @AnTheophanous.

The objective of this essay is to assess the current phase of the Cyprus problem almost 50 years after the Turkish invasion on July 20th, 1974, and submit a brief comprehensive proposal for its resolution, utilizing an evolutionary process.

The last informal five-party conference under the auspices of the UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres on April 27-29th, 2021, ended without any tangible result. Despite not issuing a joint press release, Guterres took note of both the Turkish Cypriot position for a two-state solution and the Greek Cypriot position for a bizonal and bicommunal federation with political equality, as described in the relevant resolutions of the UN Security Council. At the time, Guterres announced his intention to take a new initiative for another five-party conference. This never took place, as the gap between the two sides grew even more.

The newly elected Cypriot President Nicos Christodoulides has stated that he will seek an upgraded role of the EU in the process and the efforts to solve the Cyprus problem. Most Cypriots, however, do not have high expectations of this. In any case though, the current position of the Greek Cypriot side for a bizonal bicommunal federation with political equality was the essence of the Turkish Cypriot position for years. However, it was an array of Turkish maximalist claims that eventually prevented such an outcome. With its current position that supports a two-state solution, the Turkish side aims at eventually moving toward a confederal solution. With such a settlement, Cyprus as a whole will become a puppet state of Turkey. This will be the likely outcome of any attempt by the UN Secretary-General “to square the circle.”

It is important for the Greek Cypriot side to explore a new approach, as the policy it pursued for so many years has failed. The Republic of Cyprus should submit guidelines for a sui generis federal model, which will devote due attention both to the communities and the rights of individual citizens. Any prospective settlement should be the outcome of amending the 1960 Constitution, rather than enacting a new one. The amendment can be shaped with institutional arrangements promoting cooperation on governance, including the Presidency, security considerations, the Supreme Court, territorial, and property issues. Above all, it is essential to ensure that the Republic of Cyprus functions as a normal state after the settlement, as Guterres himself acknowledged in 2017. Furthermore, President Christodoulides in his capacity as Head of State—and not the Greek Cypriot community leader—has the legitimacy to request from the two (out of three) guarantor powers, namely the United Kingdom and Greece, as well as the EU, to contribute decisively to the reestablishment of the territorial integrity of the Republic of Cyprus. The proposed approach necessitates an evolutionary process, including confidence building measures (CBMs). In this respect, I reiterate and/or update the comprehensive ideas which I have already proposed.

The further enrichment of these ideas would be a legitimate and substantial step towards overcoming the current deadlock. While the policy pursued thus far has been questioned by various political forces, an alternative comprehensive approach was never proposed until now. Such an approach is imperative as there is not much difference between a decentralized bizonal bicommunal federation with two constituent states and a confederal solution.

This essay was finalized more than a year after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. During this period there have been tectonic changes in the international system. Unsurprisingly, the Cypriots have compared the West’s position on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine with that on Turkey and its ongoing occupation of the northern part of Cyprus as well as other violations of international law.

Historical Background and Context

Cyprus gained a fettered independence in 1960 with Greece, Turkey, and the UK being the three guarantor powers. From the early days, it appeared that the path of the Republic would be uneasy and turbulent. It is essential to underline that Greek Cypriots were not satisfied with the overall arrangements. Not only was the objective of the liberation struggle against the UK not achieved—enosis (unification with Greece)—but the imposed constitution also provided excessive privileges to the Turkish Cypriots.

In 1963-1964, there was intercommunal violence and the threat of Turkish invasion loomed large. At the beginning of the crisis in December 1963, the Turkish Cypriots withdrew from the government. Furthermore, many Turkish Cypriots relocated themselves into enclaves for security purposes, as they claimed. Greek Cypriots, however, saw this move as a preconceived step to create conditions for the partition of Cyprus. The Republic of Cyprus continued to function under the doctrine of necessity, which was legitimized by Resolution 186 of the UN Security Council in March 1964.

Intercommunal strife continued and in early August 1964 Turkish planes bombed parts of Cyprus on several occasions. Greece started deploying a military contingent to Cyprus following the spring of 1964 with the objective to defend the island from a Turkish invasion. Galo Plaza, a Special Envoy of the UN Secretary General U Thant at the time, released his report in 1965, which basically argued that there was no basis for the federalization of Cyprus as the Turkish side was requesting. Instead, he suggested steps toward an integrated society and a unitary state. At the same time, the report did not support the Greek Cypriot objective for enosis.

On April 21st, 1967, a military regime came to power in Greece. In the fall of the same year, a new crisis broke out over Cyprus. A Turkish invasion was eventually averted, following American mediation, as Greece agreed to withdraw its military contingent from Cyprus. Cypriot President Makarios insisted on maintaining the Cypriot National Guard and was successful in securing it. Ironically, the Junta used the National Guard, which was led by mainland Greek officers, to overthrow Makarios on July 15th, 1974.

In 1968, intercommunal negotiations began for the solution of the Cyprus dispute on the basis of a unitary state following Makarios’s official announcement by which the objective of enosis was put aside. Despite the difficult domestic and foreign environment, it seemed possible to reach a settlement. Cyprus entered into an Association Agreement with the then European Community (EC) in 1973. It is also worth noting that during the period 1960-1973, Cyprus’s annual rate of real economic growth was 7 percent.

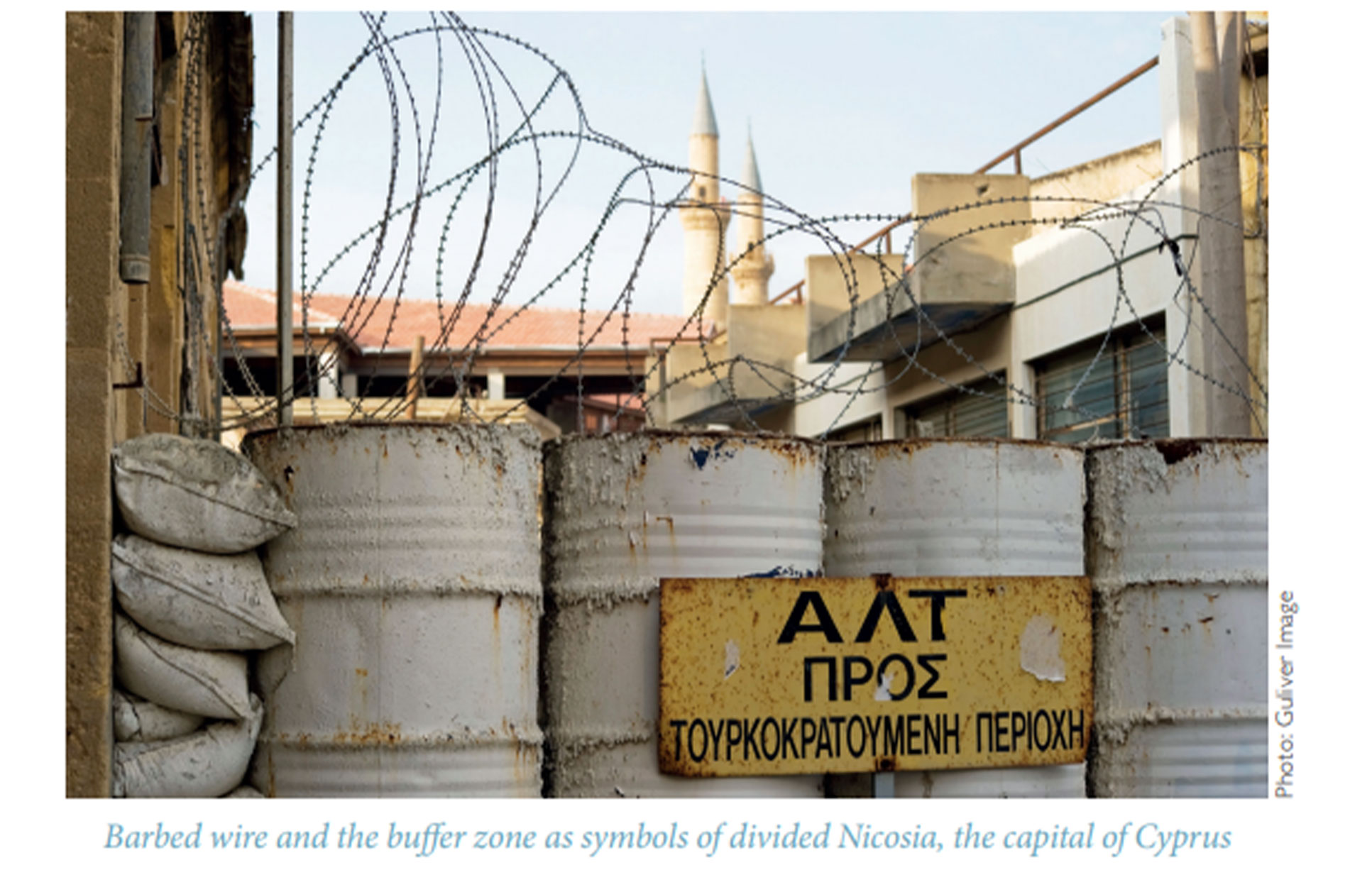

Unfortunately, this promising path and record was interrupted by the coup of the American-led Greek Junta against Makarios. Turkey invaded Cyprus five days later, on July 20th, 1974, claiming that its objective was “to reestablish the constitutional order and to protect the Turkish Cypriot Community.” On July 23-24th, both the Greek Junta and the putschist regime in Nicosia collapsed. However, Turkey did not cease hostilities. It continued to violate the ceasefire, which was agreed on July 22nd. Following the collapse of the negotiations in Geneva (the Greek Cypriots did not accept the ultimatum of Ankara which amounted to terms of surrender), Turkey launched a new attack on Cyprus on August 14-16th by land, air, and sea and captured 37 percent of the territory of the island. The international community did not react; it only made statements and issued resolutions for the respect of the independence, territorial integrity, and sovereignty of the Republic of Cyprus. It also called for the resumption of negotiations between the two communities for the solution of the Cyprus problem. In one way or another, Turkey, the country which invaded and conquered 37 percent of the Cypriot territory, was treated as a third party to the conflict.

The socioeconomic and political repercussions of the invasion were devastating. In addition to the casualties and the missing persons, Cyprus also suffered ethnic cleansing, which was the primary outcome of the Turkish military advance and the brutalities that took place. It also lost the international airport of Nicosia and the port of Famagusta. Furthermore, as most of economic activity was concentrated in the occupied territory, the country found itself in an extremely difficult situation. Almost 40 percent of the Greek Cypriot population became refugees in their own country. In addition, thousands of Greek Cypriots sought opportunities in other countries as the economy also became dislocated.

The Cypriot leadership had to deal with very harsh realities. Under these extremely difficult circumstances the country managed to survive, and the Republic of Cyprus continued to exist. The Greek Cypriots achieved what was subsequently described by others—including prominent magazines such as The Economist—as “an economic miracle.” This included the fast economic recovery which proved to be critical for the continuity of the Republic of Cyprus under very difficult circumstances. It is important to mention that by the beginning of the 1980s Cyprus began to experience an inflow of population. This, basically, consisted of Greek Cypriots who had left the country after 1974 and even before.

In 1975, Cyprus renewed the Association Agreement with the EC. Although the Cypriot government had higher expectations at the time, this agreement did not lack in political significance.

Cyprus’s impressive economic record allowed the country to continue functioning and to also have positive expectations. At the same time, however, the Cyprus problem remained the major national issue, which dominated the political agenda. It is also essential to understand that there was bitterness toward Greece, the UK, the United States, and the West more broadly because of their responsibility for the Cypriot tragedy in 1974.

In this climate, Greece tried to convince the Greek Cypriot leadership that closer relations with the EC and an eventual membership could facilitate a solution to the Cyprus question. Furthermore, such a policy option, Athens believed, would benefit Cyprus in many other respects.

Gradually, a paradigm shift began to take place in Cyprus. Yes, there was bitterness toward the West and the feeling of being let down in 1974—by Greece as well—but the most pragmatic perspective was to be forward-looking. Greece was now a democratic nation, and it could not be held responsible for the actions of the American-led Greek Junta. Moreover, the EC was gradually becoming a serious player in international relations and, furthermore, could not be held accountable for British and American actions and omissions in 1974. In the new era, it was also essential for Cyprus to come closer to nations that shared a similar value system.

Given the new political climate and strong encouragement coming from Greece, Cyprus pursued a Customs Union Agreement with the EC in accordance with the provisions of the existing Association Agreement between the two sides. Several European nations had reservations regarding the prospect of signing such an agreement with Cyprus, considering the political situation on the island and the implications for Turkey. Greece, however, had made it clear that without the Customs Union with Cyprus it would veto the accession of Spain and Portugal in the EC. The Customs Union Agreement between Cyprus and the EC was ratified in October 1987 and entered into force on January 1st, 1988. This agreement had great political significance: if in the absence of a solution to the Cyprus problem the EC had reached a Customs Union Agreement with the Republic of Cyprus, accession without a solution would also be possible.

From the economic perspective, it is doubtful whether Cyprus has made gains. Following the implementation of this agreement, the relative importance of the primary and secondary sectors of the economy continued to decline. Simultaneously, the tertiary sector continued to grow.

Cyprus’s EU Accession

On July 4th, 1990, Cyprus submitted an application for membership in the EU. President Giorgos Vassiliou made this decision despite the opposition to the move from the left-wing AKEL party, which was backing him. AKEL officially changed its stance only in 1995. Furthermore, the UK, one of the three guarantor powers of the Republic of Cyprus, had strong reservations. The UK advised Vassiliou to focus on the negotiations for the solution of the Cyprus issue and seek accession only after its resolution.

Turkey also opposed this move by the Republic of Cyprus. Greece was a staunch supporter of the application of Cyprus to become a member of the EU. Moreover, the vast majority of Greek Cypriots were in favor of the application for membership in the EU. Indeed, Vassiliou was well aware of this, which tipped the scales in favor of this decision, despite his initial hesitation. Above all, he was eventually convinced that this was the appropriate policy step to take.

Greek Cypriots at the time had a rather idealistic view of the EU and also developed great expectations. They believed that it was a Union in which the rule of law prevailed, and a democratic value system reigned supreme. Furthermore, they also believed that solidarity among member states was a value adhered to both in theory and practice. This implied that once Cyprus would become an EU member state, the Union would not tolerate the occupation of the northern part of the island by Turkey as, after all, this would be European territory.

In addition, Greek Cypriots also believed that the standing of Cyprus in the regional and international arena would be improved. There was also a prevailing perception that the value system of the EU as well as its institutions would benefit Cyprus.

In June 1993, the European Commission issued its “Opinion on the Application of the Republic of Cyprus for Membership.” This island state was considered eligible for membership, as it had a democratic system of government and a vibrant economy. Any shortcomings, it was thought, could be addressed accordingly in due time. Nevertheless, the anomaly with the division of Cyprus was a major issue which, according to the European Commission, should have been addressed before accession to the EU. Cypriot policymakers knew that the Cyprus problem was unresolved due to Turkey’s position. Nevertheless, they expressed their satisfaction with the Opinion of the European Commission and vowed to work and act in the best possible way to move on with the accession process.

There was a growing belief in the United States and various influential circles of the EU that the Cyprus problem and the Greco-Turkish disputes could be addressed constructively within the framework of the Union. The prevalent policy perspective was to offer Turkey the prospect of becoming a member of the EU. This, it was thought, could open the way to resolving the Cyprus problem and all issues between Greece and Turkey.

In March 1995, a major step forward was made. The EU offered Turkey a Customs Union Agreement, which was not vetoed by Greece; Cyprus was to start accession negotiations with the EU, 18 months after the end of the then Intergovernmental Conference; and Greece received a new financial protocol. This was another major step for Cyprus. Ankara also considered that this was an important development which could address multiple objectives.

Accession negotiations between Cyprus and the EU began in March 1998. At the time, Cypriot President Glafcos Clerides invited the Turkish Cypriot leadership to join the Cyprus negotiations team. This offer was rejected, however.

In December 1999, a major decision regarding Cyprus was made at the Helsinki European Council. The EU considered the accession of a reunified Cyprus to the EU desirable but in the absence of a solution this would not be an obstacle to membership. At the same time Turkey was offered candidacy for membership.

The accession negotiations between the EU and Cyprus were taking place simultaneously with renewed efforts to resolve the Cyprus problem. The Cypriot negotiating team knew that the Cyprus’s territorial problem could create complications; consequently, one chapter after another was closed without the best possible elaboration of the discussed issues. In other words, under different circumstances, Cyprus could have secured a better agreement on various issues.

The negotiations for the solution of the Cyprus problem were not progressing well. It was evident that there was a serious gap in the positions of the two sides. When UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan finalized his Plan for a settlement shortly before accession, the Greek Cypriots found it grossly biased. Indeed, in the referendum that took place on April 24th, 2004, a few days before the country’s accession to the EU, 75.8 percent of the Greek Cypriots voted against, while 65.6 percent of the Turkish Cypriots (and the settlers) voted in favor of the proposed Plan.

There is no doubt that the U.S., the UK, and other countries wanted to facilitate Turkey’s European path. Yet, the occupation of the northern part of Cyprus by Turkey was an obstacle. In a cynical act of political expediency, they directed their pressure towards the weaker side. The Annan Plan satisfied all Turkish objectives. In the event of a simultaneous “Yes,” the European path of Turkey would gain pace, while at the same time Ankara would have achieved its objectives in Cyprus. In the case of a rejection by the Greek Cypriot side—which is what ended up happening—Turkey would not be held responsible for the continuing stalemate in Cyprus and could proceed with the pursuit of its European ambitions anyway.

The Role of the UN

Over time, Cyprus had built up great expectations of the UN. And while the stance of the UN was positive for the Republic of Cyprus before 1974, there have been drastic changes since the invasion and the resulting situation. Despite the primacy of the occupation over other dimensions of the Cyprus problem, the Security Council adopted a neutral position and supported bicommunal negotiations. This procedure has been sustained irrespective of the fact that the Turkish Cypriot leadership is not in a position to take any major decisions without the approval of Ankara.

While there are justified disappointments with the stance of the UN after 1974, it is important to understand that the functioning of this Organization is influenced by political realities and the balance of power. In addition, in various conflicts where the UN acts as an intermediary, it does not usually take a position on the substance of the conflict. Consequently, any illusions about the role of the UN should be put aside. Indicatively, it is also worth noting that the ex-Director General of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Israel and Professor Emeritus of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem Shlomo Avineri stated in 2004, in relation to the Annan Plan, that it reflects a position which amounts to “the UN’s and the EU’s favorite occupation.”

During the informal five-party conference on 27-29th April 2021, the Turkish Cypriot leader Ersin Tatar, with the support of Ankara, submitted a proposal for a two-state solution. This proposal is outside the mandate of the UN Security Council. The reaction of the Greek Cypriots to this was rather modest; perhaps for fear of a termination of the Secretary-General’s mandate to continue pursuing solutions to the Cyprus problem. Such an act would constitute a blackmail of the Greek Cypriot side, which, given the realities on the ground, is militarily disadvantaged. One should also be reminded that the systematic concessions made by the Greek Cypriot side since 1974 have to a great extent been a result of the military imbalance on the island and in the Eastern Mediterranean.

In any case, it is clear that the Secretary-General can only make suggestions. A change or termination of the mandate could take place only after such a decision has been reached by the UN Security Council. Until such a decision is made, or any other course of action is approved by the Security Council, the Secretary-General is bound to follow the resolutions that describe his mandate.

The tolerance that the Secretary-General has shown toward Turkey’s actions in the occupied part of Cyprus tends to undermine the credibility of the UN itself. Even the terminology used is unfortunate, to say the least. For example, the terms “North” and “South” should be avoided by the UN. While according to the 1960 Constitution the two communities are in equal standing, the Republic of Cyprus and the illegal “Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus” (“TRNC”), are not equal. It is essential to convey the message that there is one legitimate member state of the UN and the EU on the island, the Republic of Cyprus. Then, there is the “TRNC,” an occupation entity that has been created and recognized only by Turkey. Consequently, there cannot be negotiations on the basis of two states.

The EU’s (Passive) Role

When the Republic of Cyprus applied for membership in the EU in 1990, there were high expectations. Among others, there was a widespread conviction that the value system of the Union and its institutional framework in conjunction with the European ambitions of Turkey could contribute to a just resolution of the Cyprus problem. However, these expectations have not been fulfilled.

The moral high ground of the Republic of Cyprus was eroded with the rejection of the Annan Plan in 2004, while the occupying force, Turkey, claimed that it had done its fair share in trying to reach the solution to the problem. The reality, though, was different. While the Annan Plan satisfied most of the Turkish demands, most Greek Cypriots felt that its implementation would have dissolved the legitimate state, and that their position would have deteriorated. In addition, the EU did not exhibit the appropriate solidarity toward the Republic of Cyprus, while, at the same time, its tolerance for Turkey remains almost unlimited. This is because the various dimensions of the Euro-Turkish relations—and the entangled political and economic interests—weigh much more than solidarity and other EU values.

The reaction of the EU in view of Turkey’s systematic violations of the Cypriot exclusive economic zone (EEZ), the continuing colonization, and the hybrid warfare against Cyprus, was very limited. This persists even following the new fait accompli in the fenced city of Varosha and the involvement of Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in the election campaign for the new leader of the occupation regime in October 2020. Therefore, it comes as no surprise that the efforts of the Cypriot government at convincing the international community to impose sanctions against Turkey have not yielded any results so far.

In the informal five-party conference on 27-29th April, 2021, the presence of the EU was downgraded due to Turkey’s insistence. Moreover, in the discussions for the future of Cyprus, two out of the three major guarantor powers, which are not members of the EU, namely the UK and Turkey, were present. Meanwhile, the EU, of which Cyprus is a member, was in essence a mere spectator. Consequently, it appears that a dismal precedent has been created for the Greek Cypriot side. The Cypriot President at the time, Nicos Anastasiades, should have been more demanding on this issue. But, above all, the EU itself should not have accepted its downgrading.

It is interesting to compare the position of the EU toward the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the ongoing Turkish occupation of the northern part of Cyprus. Although by definition each case has its own characteristics, there are also some common issues. In both cases there have been violations of international law. In the case of the Russian invasion, the response of the EU was firm and punitive. In the case of Cyprus though, Turkey has been tolerated and accommodated. This is because Russia is considered a foe while Turkey is perceived as a strategic partner.

A Normal State After the Solution

During the discussions for the Annan Plan, those who were against it were asked about their proposals, given their stance. In addition to the analysis of various models that could be adopted in Cyprus, I have since 2002 argued that it is essential to have a normal state. It was therefore with satisfaction that I heard in 2017 the use of this term by the then President Nicos Anastasiades, Greek Foreign Minister at the time Nicos Kotzias, and the UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres.

In this regard, it is essential to have in mind some guidelines as follows:

The evolution of the Republic of Cyprus. The continuity of the Republic of Cyprus should be ensured within the framework of the resolution of the Cyprus problem. It is inconceivable for a UN and EU member state to voluntarily cease to exist, equate itself with the Turkish protectorate “TRNC,” with which it would then seek to create a new common state after mutual recognition.

Until recently, the basis of negotiations, which is codified in the relevant resolutions of the UN Security Council, if successful would lead to the creation of a dysfunctional political system based on ethnonationalist pillars. Such an outcome would worsen the status quo.

Consequently, the starting point should be the 1960 Constitution, which would be amended. After all, when Turkey invaded in 1974, it declared that its major objective was the reestablishment of the constitutional order. We should be reminded that, today, the Republic of Cyprus functions on the basis of the doctrine of necessity, which was legitimized in March 1964 with the Resolution 186 of the UN Security Council.

Guarantees, Foreign Troops, and the Cypriot Army. The current system of guarantees should be put aside or at least be revised, given that it was one of the sources of the problem. The UN Security Council could have a special role in this system. It is in any case paradoxical for any EU member state to have guarantor powers, two of which are not even members of the Union. By the same token, there must be no foreign troops in the Republic of Cyprus.

While all foreign troops for which there is no provision in any treaty should be withdrawn, it would be useful to have an enhanced, strengthened multinational force under the auspices of the UN for a provisional period.

It is also noted that in this sui generis federal state, there should be a Cypriot Army on the numerical base of 3:1.

Presidency and Governance. After the referendum of 2004, I submitted the proposal for a common ticket for the President and Vice President, who should not be from the same community. This suggestion, which emanates from an integrationalist federal philosophy, is democratic, and, in addition, encourages the creation of common objectives.

The provisions for double majorities in the decisionmaking process should be revisited. Double majorities, even the strong ones (i.e. 66.7 percent), should always apply in the cases of constitutional amendments. For certain serious issues, there should be provisions for enhanced (and not absolute, i.e. 40 percent) double majorities, while on other issues there should only be a simple majority of those voting (irrespective of their ethnic origin).

Taking into consideration the mixed composition of various bodies, as well as the equal representation in the Upper House, we can presume there will always be effective Turkish Cypriot participation in the decisionmaking process.

The Supreme Court should consist of four Greek Cypriot and four Turkish Cypriot judges and one judge from the other three smaller communities (Maronites, Armenians, and Latins) of Cyprus. It is notable that in the plan that had been finalized before the 1974 coup, there was a provisional agreement for six Greek Cypriot and three Turkish Cypriot judges. In the Annan Plan, the relevant provision provided for three Greek Cypriot, three Turkish Cypriot, and three foreign judges.

Bicommunality. The philosophy of bicommunality should be considered as an integral but not exclusive element of the solution framework. The same number of Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot Senators in the Upper House secure the political equality of the two communities. Nevertheless, it is not possible to address all issues with the perspective of bicommunality. This is why one of the ideas that is being advocated in the issue of the Presidency is based on a federal philosophy of integration.

The Importance of the Economy and a Modern State. The content of a solution of the Cyprus problem should be enriched with the rules of smooth operation of the economy, society, and the institutions of the contemporary state. At the same time, it is essential to take into consideration the European acquis and, in general, the overall developments in the EU. Among other things, the creation of a unified economy is vital. The market economy should be considered a necessity, though not a sufficient condition for the convergence of the standard of living between the two communities.

Settlers. Colonialism is by definition a war crime, while at the same time it entails political dimensions. The ultimate objective of Turkey is the gradual demographic transformation, not only of the occupied territories but of Cyprus as a whole. Consequently, this issue is serious. It is within this framework that the relevant humanitarian issues should be assessed. The relevant agreement between former Cypriot President Demetris Christofias and Cypriot Turkish leader Mehmet Ali Talat for maintaining the demographic base 4:1 and its implementation is of vital importance.

The Territorial and Property Issue. The importance of the territorial issue would be altered if two constituent states were to be replaced by six regions. If the Turkish Cypriot community insists on one indivisible region under its own administration, then this should be accepted. In such a case, this should be a region, or, at most a component state, but certainly not a constituent state.

The property issue can be addressed within the framework of the tentative agreements made so far, as well as within market forces. A compensation fund, endowed from foreign sources as well, would be supportive of the efforts to resolve this thorny issue. Nevertheless, a considerable amount is not expected to be secured.

The Turkish Cypriot region, which would make around 28.7 percent of the territory, would have the broadest possible autonomy. In the territory under Greek Cypriot administration, it is possible to have five regions. This arrangement would not affect the composition of the Upper House which would be split 50-50.

Cooperation. It is of vital importance to encourage the creation of an environment of cooperation between the two communities and the promotion of a framework with common objectives. Without such an environment, any attempt at state-building would be futile. The above chapters may be explored and expanded even more. In addition to the evolutionary approach, a positive attitude of Turkey would also be significant. Undoubtedly, it is extremely difficult to expect that such ideas would be accepted by Turkey. On the other hand, implementing what until recently made the negotiating framework would lead to a dysfunctional state and further deterioration. Consequently, the proposed philosophy must by all means be promoted, as it maintains the prospect of an eventual settlement. To this end, hard work, multilateral cooperation, a pragmatic foreign policy, an effective state, and a comprehensive narrative will be required. And while the Republic of Cyprus will continue to work for a settlement of the Cyprus issue, it must at the same time continually enhance its defense capabilities to face the Turkish expansionism.

The Evolutionary Process

It is essential to understand that it is impossible to have a federal solution and transition to this new state of affairs in 24 hours. Even in the best-case scenario, in which there was no distrust, suspicion, and a heavy historical past, an evolutionary path and approach would still be required. It is also important to underline that the narratives of the two sides are quite opposite. The fulfillment of several prerequisites is necessary for building a viable federal polity, the principal of which should be a minimum framework of common objectives. Currently, such a framework and a common vision for the future do not exist.

Despite a very difficult situation, the submission of suggestions for the following major CBMs and a parallel discussion on the guidelines for a settlement may prove useful and create new momentum.

First is co-exploitation of energy sources by both Greek and Turkish Cypriots with the simultaneous de facto delimitation of the EEZs of Cyprus and Turkey. Such a development would also help facilitate Greco-Turkish dialogue. The parallel delimitation of the EEZ between Greece, Turkey, and Cyprus could also be proposed by the Greek Cypriots. A common recourse to the International Court of Justice in The Hague would facilitate such a development.

Another CBM would be acknowledging the occupied territories as the Region under Turkish Cypriot administration with the implementation of the acquis communautaire. It is important that the EU assumes its responsibilities in the process of harmonization of the occupied territories of the Republic of Cyprus with the acquis communautaire. Such an action would most likely upgrade relations between the Turkish Cypriots with the Cypriot central government and especially with the EU.

Next is the return of legitimate residents and their beneficiaries to the fenced city of Varosha under Greek Cypriot administration.

A crucial measure would also be a gradual return of territories under Greek Cypriot administration. With the beginning of normalization, the occupied village of Achna should be immediately returned under Greek Cypriot administration, and the utilization of the entire Buffer Zone should commence without delay.

Similarly, the functioning of the airport of Tymbou and the port of Famagusta (in the occupied part of Cyprus) under the auspices of the UN and the EU should be enabled. The implementation of such measures would take place in a way that the legal status of the Republic of Cyprus would not be negatively affected.

Turkey should implement the Ankara Protocol. Such an action entails the implementation of the Customs Union Agreement of Turkey with all member states of the EU, including Cyprus.

Part of the normalization would be the further encouragement of trade between the two sides; the necessary legal and health standards would be taken into consideration.

Turkey should end its colonization of the occupied territories and hybrid warfare it continues to wage against the Republic of Cyprus. These issues concern not only the Greek Cypriots, but also the Turkish Cypriots and the EU.

The parties should discuss issues of common interest, such as the extension of cooperation and addressing the concerns of the two sides within the framework of a sui generis federal model. It is essential that the 1960 Constitution based on consociational democracy is amended in a way that will include elements of an integrationalist federal model.

Turkey should assume its responsibilities. We should be reminded that when Turkey invaded Cyprus on July 20th, 1974, it claimed that its objective was the reestablishment of the constitutional order and the protection of the Turkish Cypriot community. Consequently, it has to contribute toward this direction by gradually normalizing its relations with the Republic of Cyprus; the first steps would include the withdrawal of the occupation troops.

In the next elections for the European Parliament, the EU should offer two extra seats to Cyprus that will be taken by Turkish Cypriot residents of the Region under Turkish Cypriot administration. These two MEPs would come from the Republic of Cyprus.

Any solution should be the outcome of a voluntary agreement between the two sides in Cyprus. For such a development it is essential that Turkey respects the right of the Republic of Cyprus to exist. An evolutionary approach would provide the required time for the gradual strengthening of the relations between the two communities and the forging of the concept of an integrationalist federal model. In case that this is not feasible, other ways should be sought to promote peace and security within the framework of the participation of the entire territory of Cyprus, given that this has been ensured by the EU accession in 2004, including Protocol 10. This cannot take place on the basis of two independent states. It is possible, however, for one region to exist under Turkish Cypriot administration, which would have the greatest degree of autonomy.

In case such measures are implemented, great benefits would accrue for all the parties involved; in addition, tensions in the Eastern Mediterranean would be drastically reduced. It is understandable that for the implementation of such measures the consent of Turkey is indispensable. Even in the most likely case that these suggestions are rejected by the Turkish side, the Republic of Cyprus would even more rightfully claim moral high ground and create a road map for more favorable conditions to resolving the Cyprus problem. Although this may not be possible at the moment, the prospect for positive developments in the future would nevertheless be maintained.

A Conundrum in a Nutshell

The question that arises on a theoretical level is whether the 1960 London-Zurich Constitution could have been functional. However, such a constitution would require tolerance, mutual understanding, maturity, and mutual respect—characteristics that were lacking in 1960 and remain insufficient today. Therefore, a viable and functional settlement based on a bizonal bicommunal federation is not possible under current circumstances. It should be noted that a legitimacy deficit, similar to the one that existed during the birth of the Republic of Cyprus, would reoccur if a settlement is perceived as a result of imposition. This conclusion takes into account all relevant factors.

In addition, while federation has been discussed all these years, there is no adequate understanding of the federal systems and the different approaches to them. There are federal polities/systems that are not based only on ethnonationalist pillars and consociational democracy—a fact that is not well understood. Other forms of federation, especially those stemming from the integrationalist federal philosophy, were ignored. The American system is one such example, where the Constitution secures the rights of citizens irrespective of their ethnic origin and religious beliefs. Moreover, it does so without relying on ethno-communal pillars. Notably, John F. Kennedy was elected in 1960 not because it was the turn for a Catholic to become President, but as a triumph of politics. The same happened with the election of Barack Obama, an African American politician, in 2008 and 2012. This is a response to the request of the Turkish Cypriot side for a rotational presidency.

Judging by their results, the endless cycles of bicommunal negotiations since 1974 have obviously failed to produce a solution for the Cyprus problem. While the negotiating framework has since 1974 moved closer to the Turkish positions, Turkish maximalism continues to stand in the way of solutions. Despite the passage of time, the Greek Cypriots should promote a new negotiating framework based on a federal approach. This should be done in a way that would acquire both domestic legitimacy and external support. With Ersin Tatar as the leader of the occupation regime that insists on a two-state solution, the Greek side should take the initiative and come up with a new approach.

Among other ideas for a new approach, it is possible to stress that there is a legitimate state in Cyprus on the one hand, and an illegal occupation entity on the other. In addition, any federal arrangement must take into consideration four decisive factors:

- the Constitution;

- the events of 1974;

- the accession of Cyprus to the EU and subsequently the Eurozone;

- the relevant resolutions of the UN Security Council.

Taking into consideration the suspicion and the absence of common objectives between the two communities, we must adopt an evolutionary path and process. The discussion must include the reassessment of the federal system within the framework of a settlement. Understandably, though, no development can take place without the consent of Turkey.

It would be a pleasant surprise if Turkey changed its policy and accepted a functional compromise. In this regard, the evolutionary process and the CBMs would facilitate finding a sui generis federal solution for the Cyprus problem. In such a polity, the region under Turkish Cypriot administration would have the greatest possible autonomy. At the same time, there would be effective participation in the institutions of the federal state. Gradually building a minimal framework of common objectives would also be feasible.

However, the expected scenario is the insistence of Turkey on a settlement in which the Republic of Cyprus would be pushed aside and the new three-headed entity that will be created would, in essence, be a Turkish protectorate. Obviously, the Republic of Cyprus would not dissolve itself. Under these difficult circumstances, the republic must continue to function with the doctrine of necessity. The official state has the legitimacy to take all necessary decisions for its survival, including making additional constitutional amendments and strengthening its defense capabilities.

Finally, the projection of a narrative is indispensable. If Turkey continues to insist on its expansionist policy, it would be appropriate to point out that Ankara denies minority rights for the millions of Kurds of Turkey, while in Cyprus it demands a two-state solution. This is a great contradiction, which only undermines the official Turkish narrative.

With its militarization and islamization of the occupied part of Cyprus, the Turkish demands are removing the possibility of reaching a final settlement. It is also essential to note that since April 2021 the Turkish side has escalated its two-state-solution rhetoric. Most likely, however, the Turkish objective remains a confederal settlement through which Ankara would exercise strategic control over Cyprus as a whole. It is worth noting that the Turkish Cypriot leader Ersin Tatar stated on September 10th, 2021 that Cyprus should be returned to Turkey.

Erdoğan tried to promote the two-state solution narrative while addressing the UN General Assembly on September 22nd, 2021. This was repeated in September 2022. It may be appropriate to raise the question whether Erdoğan’s recommendations for the Cyprus problem could also be applied to the Kurdish issue in Turkey.

In either case, Cyprus must have a comprehensive policy. In addition to adopting a holistic approach and submitting specific proposals for the Cyprus problem, continuing to strengthen the state entity is very important. The maximum objective is the reestablishment of the territorial integrity and the end of the Turkish occupation. The minimum objective is the protection and security of the free part of Cyprus. Simultaneously, it is imperative that the Republic of Cyprus strengthens its defense capabilities. Furthermore, the widening and deepening of cooperation networks with other powers is indispensable. In addition, Cyprus should ask Greece and the UK to coordinate their efforts as guarantor powers and work toward the reestablishment of its unity and territorial integrity.

Undoubtedly, the accession of Cyprus to the EU on May 1st, 2004, and the adoption of the Euro on January 1st, 2008, were great achievements. Nevertheless, the expectations of Cypriots were not fulfilled. To the contrary, there were several disappointments. Be that as it may, it is important that Cyprus does its best as an EU member to advance its own objectives while making a notable contribution to the European project.

While the EU reacted strongly to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, it has been very tolerant of Turkey’s actions in Cyprus. Despite the rhetoric, the EU did not take any measures that would make Turkey pay for its actions. To the present day, Turkey does not recognize the Republic of Cyprus and has not yet implemented the Ankara Protocol in a way that includes this island state. Furthermore, Ankara has systematically been violating the Cypriot EEZ and waging hybrid warfare against the island state. All this undermines peace, stability, and cooperation in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Although the EU’s position on the Cyprus problem has not lived up to the expectations of Cypriots, or for that matter, to its own value system, it is also important to underline that the island state should have made a better effort to present its case. It is essential for Cyprus to have a narrative and a comprehensive vision for the future. Although it may be extremely difficult, if not impossible, for the EU to promote a sanctions policy against Turkey, it could advance a policy that will ease tensions on the island and pave the way for some major steps forward.