Mohammed Benhamou is President of the Moroccan Center for Strategic Studies. An earlier version of this essay was published as part of the AUSACO Papers series in November 2022, the publication of the Autonomy for the Sahara Coalition (AUSACO).

Mohammed Benhamou is President of the Moroccan Center for Strategic Studies. An earlier version of this essay was published as part of the AUSACO Papers series in November 2022, the publication of the Autonomy for the Sahara Coalition (AUSACO).

Despite the progress recorded in the past two decades in Africa, the continent remains weakened by the persistence of various intra-state crises and conflicts. Interregional interference, amplified by globalization, promotes the proliferation of new threats that further fuel violence and draw the region into a vicious cycle.

Two major peculiarities mark the new African security landscape. On the one hand, there is the strong participation of non-state actors who benefit from the bankruptcy of certain states and the porosity of borders to act freely and with impunity. There is, on the other hand, the proliferation of separatist movements exploited by other powers to carry out proxy wars for hegemonic purposes.

In this context, the security landscape of the Sahel remains of particular concern.

The vital space at the hinge between the Mediterranean and Sub-Saharan Africa, is a privileged route for the passage of illicit traffic between Africa and Europe and a grey area that is difficult to control, given endemic conflicts. The Libyan and Malian crises are amplified by a strong hybridization between criminal networks and jihadist groups.

Aware of this threatening security situation, Morocco contributes significantly to efforts to preserve peace and stability in the region. Morocco’s African strategy is based on an assessment of the vulnerabilities of Africa and the Kingdom’s assets, with the common thread being the need to confront the risks of terrorism and transnational organized crime as well as to develop new approaches to resolve the issue of migration.

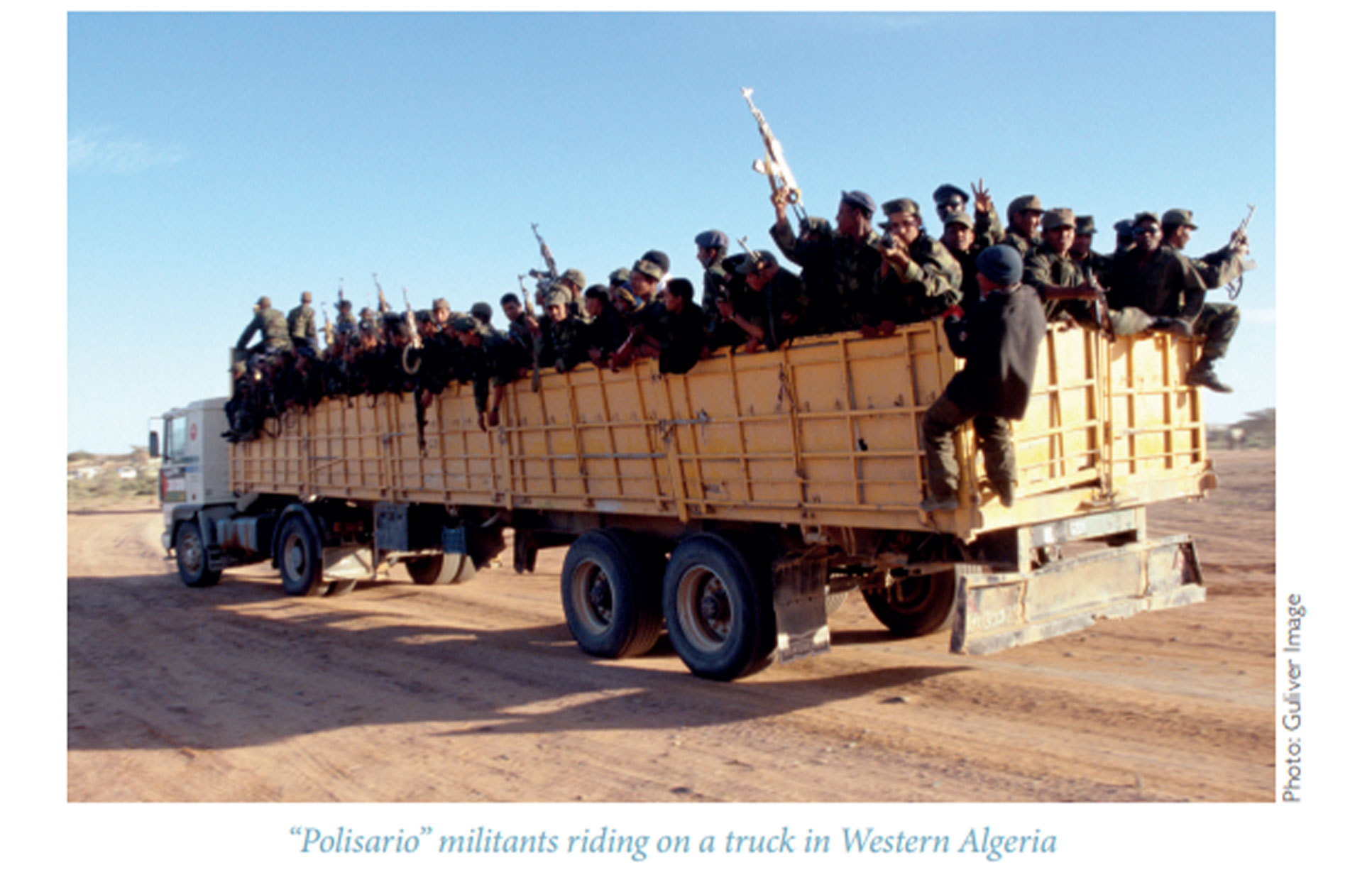

However, the Kingdom’s efforts confront the conflict with Algeria around the Moroccan Sahara. Encouraged by hegemonic ambitions and making the weakening of Morocco the central objective of its strategy, the Algerian regime exploits the conflict through unprecedented financial, military, and diplomatic support to “Polisario.” The dazzling failure of the separatist thesis of this armed movement, the diktats of its leaders and the precarious living conditions in the Tindouf camps push its members towards crime. In addition to their involvement in illicit trafficking, favored by the porosity of borders and anarchy in the camps, its members become easy prey for extremist groups. In other words, “Polisario” has long been a source of instability and insecurity in the region.

After highlighting the magnitude of instability in the Sahelian space and Morocco’s efforts to improve the security outlook in the region, this chapter aims to demonstrate Algeria’s deep involvement in sustaining the artificial conflict in the Moroccan Sahara and the connections that “Polisario” maintains with criminal and terrorist networks.

Insecurity in the Sahel: A Regional and International Concern

As a highly sensitive region at the confluence of Africa and Europe, the Sahel is characterized by a growing concern due to the development of a multitude of terrorist and criminal activities. These activities pose a serious threat to neighboring Maghreb countries and the European countries of the Mediterranean basin.

Dynamics of Complex Instability

To understand the security challenges facing the Sahel countries, it is necessary to consider the specificities of their geography and history, but also to be able to analyze the dynamics of their operation.

Geographically, the Sahel stretches from the Atlantic to the Red Sea, covering parts of Senegal, Mauritania, Burkina Faso, Algeria, Niger, Nigeria, Chad, Sudan, and Somalia, and is made up of more than 80 percent desert. With an average density of one inhabitant per square kilometer, several spaces are out of control and not subject to any jurisdiction. This offers tactical advantages to criminal and terrorist actors in terms of the possibility of camouflage, concealment, and mobility, especially in the absence of a common response and coordination strategy among the countries of the region, particularly in terms of the collection, processing, and sharing of intelligence. At a historical level, the political legacy and the consequences of decolonization are at the origin of structural underdevelopment and the failure of the rule of law in several countries in the region.

As for the security dynamics, they are difficult to dissect given the complex nature of the rivalry and alliance systems between different actors, which are in perpetual motion depending on broader geopolitical and social issues. The conflict in northern Mali, the political crisis in post-Gaddafi Libya, and the revolt of the Boko Haram sect in the Lake Chad basin constitute the three elements of the arc of the crisis upon which extremist and criminal groups graft themselves.

Disturbing Proliferation of Jihadist Groups in the Sahel

Terrorism represents one of the most disturbing threats in the Sahel. In addition to political, economic, and social factors, religious radicalization is the main vector of this threat. Analysis of the terrorist activity of extremist groups active in the Sahel highlights a significant increase in their numbers and great capacity to adapt to geopolitical developments in the region.

Chronologically, the number of terrorist groups continues to rise, increasing from a single organization, Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) before 2012, to more than 10 entities in 2018, operating mainly from Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger. As a result, the number of violent acts doubles every year, from 90 in 2016 to 465 in 2018. Deaths resulting from the activity of violent groups have also seen a disturbing resurgence since 2009 (from 200 in 2014 to 2,600 in 2020).

Most of these actions are the deed of three groups, namely the Macina Liberation Front, the Islamic State in Greater Sahara, and Ansar al Islam. These entities have direct or indirect links with a consortium of groups associated with AQIM known as Jama’at Nusrat al Islam Wal Muslimin (JNIM).

The proliferation of these groups and the increase in their activities highlights their proven adaptability and transformation, as well as their high organizational and coordination skills. They are capable of carrying out attacks using increasingly elaborate planning and communications tools. They have shown a remarkable ability to mobilize sophisticated assets, particularly thanks to significant revenues generated by their growing hybridization with criminal networks. This is the case of AQIM, which according to some assessments, has been able to generate an estimated income of $100 million in smuggling and illicit trafficking between 2008 and 2014.

Illicit Trafficking

Given its geographical position, the Sahel became without a doubt a new avenue for trafficking of all kinds. To reach Europe, traffickers use clandestine lanes throughout the Sahelian desert, exploiting the region’s vulnerabilities. This change of route is likely to increase pressure on the security services of neighboring countries and transit, and place them at the heart of the battle against criminal organizations.

Indeed, given its proximity to Europe, the world’s second largest drug market after the United States, North Africa is a privileged gateway. According to a report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), year 2019 has seen a record in drug seizures, amounting to 20 tons of cocaine, of which 9.5 tons were found during a single seizure.

This complex situation raises several challenges for the security services of neighboring countries, including:

The difficulty of securing borders which, given the extent of land and sea borders, require constant support to maintain the required level of operational readiness of the agencies in charge of the fight against this traffic;

The need for law enforcement agencies to continually rehabilitate the means to the new modus operandi by traffickers for established security mechanisms, which requires significant investments and perfect coordination between the relevant agencies, as well as a regular exchange of information and learned lessons;

The security conundrum, which is mainly due to the political instability of some countries, the lack of cooperation in the Maghreb and the lack of quality information, complicates the task of law enforcement agencies, especially in terms of surveillance, resource allocation, and human resources.

The Role of Morocco in Stabilizing the Sahel

In addition to effective and active participation in peacekeeping and security efforts in Africa, the security component of the Moroccan strategy in Africa and the Sahel grants a particular interest to the common fight against the emergence of new threats to stability and development in various parts of the continent.

Active participation in peacekeeping operations in Africa

Since its independence in 1956, Morocco has been involved in managing the crises that shook Africa, intervening in various conflicts either as a mediator, or directly participating in peacekeeping operations.

In addition, the Kingdom has contributed to the humanitarian support of African civilians by deploying 11 medical-surgical field hospitals complying with international standards. This growing humanitarian dimension reflects the Kingdom’s ambition to make its contribution to peace a global one, extending to prevention and peacebuilding, and to strengthen its role as a promoter of peace in its African environment.

Undeniable contribution to the fight against terrorists:

In keeping with its African policy and drawing on its proven and internationally recognized expertise, the Kingdom of Morocco is seriously engaged in the fight against terrorism in Africa and the Sahel. During a ministerial meeting of the Francophonie on “security and development in a united Francophone space,” organized on the sidelines of the work of the 72nd General Assembly of the United Nations, Morocco stated in New York its readiness to support the G5 Sahel countries (Burkina Faso, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Chad) in the field of troop training and border security.”

Aware of the scale of the fight to be waged and convinced that its security depends largely on that of parts of the Sahelian continent, Morocco has undertaken regional initiatives to combat terrorism. This is particularly the case of the Fifth Conference of Justice Ministers of French-speaking African countries, organized in Morocco in 2018 in cooperation with the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and the International Francophonie Organization, in order to ratify and implement universal instruments against terrorism.

It is also in this sense that Morocco solemnly contributes to the “Trans-Saharan Counter-Terrorism Program (TSCTP),” an inter-departmental plan launched by the United States with the aim to combat terrorism in sub-Saharan Africa through the improvement, among other things, of the ability of the Sahel region’s governments to control their territories. In addition to the United States, this partnership brings together the countries of the Maghreb, Mali, Niger, Chad, as well as Nigeria and Senegal. Its objective is to strengthen the capacities of the security forces and promote cooperation between them.

A real added value in the fight against illicit trafficking

Thanks to its geographical position and experience in the fight against transnational organized crime, Morocco plays an important role in the repression of such trafficking. That is why Morocco gathered 22 African countries from the Strait of Gibraltar to the Cape of Good Hope in August 2009. This initiative, which gave rise to the establishment of the Ministerial Conference of Atlantic African States, represents a platform that brings together all interested coastal countries to face common challenges emanating from the Atlantic Ocean façade through mechanisms of flexible cooperation and coordination.

In addition to its participation in forums, conferences, and workshops related to the fight against illicit trafficking, the Kingdom has effectively contributed to the various programs initiated by UNODC, including the Sahel program. This program began with the objective of supporting the development of effective and accessible criminal justice systems to effectively combat drug trafficking, illicit trafficking, organized crime, terrorism, and corruption in the region.

No less alarming, the arms trade has also taken on a particular dimension due to its aggravating consequences in the multiple wars that have occurred in the last three decades. Vast and poorly controlled, the Sahelian arc has been increasingly a privileged place for arms trafficking. According to UNODC estimates, between 10,000 and 20,000 weapons of different calibers have thus been disseminated across West Africa after the fall of the late Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi in 2011.

Persuaded that the uncontrolled circulation and illicit arms trafficking represent real challenges for stability, security, and state development, Morocco has actively contributed to the conclusion of the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT), approved on April 2nd, 2013 by the UN General Assembly.

A solidary migration policy

Morocco adopted a new approach to migration policy in 2014, in particular through the regularization of migrants settled on its territory. While it is true that the Kingdom remains a very popular transit country for migrants heading to Europe, in recent years, the country has also become a host with thousands of migrants deciding to settle and work there. As such, Morocco has launched a wave of regularization of irregular migrants. It was on the instructions of His Majesty King Mohammed VI that the operation was carried out in accordance with a new migration policy of the Kingdom. The first phase, which took place in 2014, involved around 25,000 beneficiaries.

Furthermore, His Majesty King Mohammed VI, in his speech on August 20th, 2017, stressed that “Morocco is among the first countries in the South to have adopted a genuine policy of solidarity to welcome sub-Saharan migrants, according to an integrated human approach which protects their rights and preserves their dignity.” It is within this framework that the country proceeded to regularize the migrants, taking into account their precarious situation and adopting reasonable and fair criteria. The aim is to create for them the right conditions to settle, work, and live with dignity in society. In the same speech and in a very symbolic and revealing gesture of the spirit of solidarity that prevails among African countries, the King of Morocco reaffirms that “we are only fulfilling our duty towards this category. Precariousness has pushed us to risk our lives.”

The launch of this regularization initiative was quickly acclaimed by migrants and beyond in several African countries. In the same timeframe as Morocco’s return to the African Union (AU), His Majesty the King Mohammed VI was designated by the President of the AU and Guinean Head of State Alpha Condé during his country’s rotating presidency, to coordinate the migration policy within the AU, with a view to preparing a dedicated roadmap. The Moroccan capital, Rabat, hosted the “African Ministerial Conference for an African Migration Agenda” in January 2018. During this meeting, the Kingdom presented a three-pronged vision articulated around three main axes:

Make migration in Africa an option and not a necessity;

Break preconceptions and stereotypes associated with migrants;

Forge a global, integrated, and holistic vision of migrations.

As such, it should be noted that the African agenda for migration proposes an approach based on national policies, regional coordination, a continental perspective, and international partnerships.

The Responsibility of Algeria

Surrounded by a long institutional crisis and marked by the dominance of the military apparatus, the Algerian regime seeks by all means to weaken Morocco, its main rival in the region. To achieve this strategic objective, it exploits the conflict around the Moroccan Sahara, through its contribution to the creation and multifaceted support to the “Polisario.” This support, presented to public opinion as a historical responsibility towards the oppressed peoples in the name of the right to self-determination of the peoples, hides hegemonic motives.

Algeria’s equivocal position masks its true motives

The in-depth analysis of the Algerian policy for the resolution of the regional dispute over the Moroccan Sahara reveals a palpable inconsistency between the official discourse of its diplomacy (which rejects any direct interference by referring systematically to respect for international law) and the flagrant reality of Algeria’s multifaceted and tireless support to the “Polisario.” Through this ambiguous position, the Algerian system tries to hide the true motivations behind the genesis and the persistence of this conflict.

Confronted with a decades-long crisis of legitimacy, the Algerian regime seeks to present itself as the defender of a national cause to distract public opinion from the deep-seated socioeconomic and governance issues facing Algeria and to gather public support around the regime. The objective of weakening Morocco is not only at the heart of this strategy, but also a red line that cannot be challenged, as evidenced by the dismissal of the Algerian officials who have shown resistance to this line of conduct or advocated a rapprochement with Morocco. However, the regional dispute seems to be a concern only for the Algerian ruling class, which failed to provoke the revival of nationalism that the regime had hoped for. The large-scale protests in recent years and the neutral attitude of the majority of Algerians strongly support this claim.

Support for “Polisario” and the creation of a satellite state on its western border also corresponds to the geostrategic and geoeconomic ambitions of the Algerian regime, which aspires to achieve unchallenged regional leadership. Algeria, which is one of the main producers of oil and gas in the world, has a single-point maritime access to the Mediterranean, and therefore seeks access to the Atlantic to diversify its logistics routes for the delivery of its oil products and reduce the cost of exports.

Algerian support for the “Polisario”: a dogmatic constant

The centrality of the Moroccan Sahara issue in Algerian doctrine and its declared, yet unfulfilled, willingness to try and neutralize Morocco, was manifested through its financial, military, and diplomatic support to “Polisario.” During an interview to French magazine Le Point, on July 13th, 2020, Algerian President Abdelmadjid Tebboune has even made support to “Polisario” a constant, indisputable dogma.

Financially, this support weighs heavily on the Algerian state budget to the detriment of other priority sectors. A study carried out by Al Watan in its edition of October 8th, 2020, reveals that the Algerian regime has spent $375 billion over the last four decades to equip “Polisario” and finance media propaganda campaigns against Morocco. This represents $8.5 billion a year, or $23 million a day and 4.7 percent of Algeria’s gross national product. The weekly is outraged by the relationship between the equipment budget, which barely exceeded $23 million in 2019, compared to the 8.3 billion generously spent in this war of attrition, that is, 23 times the budget reserved for equipment.

At the diplomatic level, Algiers has sought from the beginning of the conflict to orient decisionmaking within international organizations, forging alliances, and mounting lobbying campaigns not only at the level of the foreign ministries of the great powers, but also at the level of smaller countries. This lobbying translates in support of the separatist cause at the international level (and organizations such as the UN, AU, or EU). On the ground, the Algerian regime is seeking to mount false-flag operations in the Southern Provinces, through a sustained mobilization of separatists inside Morocco, to exploit any reactions from the police as part of its victimization propaganda.

At the media level, the Algerian regime is launching a large-scale propaganda of demonization of Morocco in the eyes of international public opinion, especially directed at NGOs, political leaders, research centers, academics, the media, and social networks. It is based on the falsification of the history of the conflict, an emphasis on the so-called legitimacy of the “Polisario,” and the exploitation of supposed human rights violations.

At the military level, Algeria supports the “Polisario” directly through the building of barracks and their equipment in means of protection and defense, and indirectly, by launching a frenzied arms race, officially justified by the climate of insecurity that looms over the region and betrays for the deployment of military installations along the western border. By so doing, Algeria is highlighting its preparation for a possible confrontation with Morocco.

With around 3 percent of world purchases, Algeria is the main arms importer on the continent, with military spending that went from 3,000 million in the late 1990s to more than 13,000 million in 2020, that is, more than 4 percent of GDP. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), Algeria tops the list of the most attractive countries for suppliers of weapons and defense equipment. However, these expenses begin to weigh heavily on the country’s economy, impacted by the fall in the price of oil, which is the main resource and represents 95 percent of income.

Internal protest against Algerian interventionism

The adamant failure of Algeria and the diplomatic feats of Morocco, combined with the catastrophic conditions of the populations within the Tindouf camps, favored the emergence of opposition groups both in Algeria and within the “Polisario.”

In an interview with the weekly magazine La Gazette du Maroc, published on March 10th, 2003, retired Algerian General Khaled Nezzar, former Algerian Defense Minister and one of the main architects of the ‘interruption of the electoral process in January 1992, clearly expressed his opposition to the Balkanization of the region and the establishment of an independent entity on the western borders of his country. At the same time, he stressed that the best solution to the conflict is Saharawi integration as part of an agreement with Morocco. In addition, several Algerian academics agree with this position, warning about the challenges posed by the creation of an autonomous state, which by nature would be fragile and easy prey for external rivalries, making the stability of the region and Europe even more fragile.

Within the “Polisario,” “the Path of the Martyr” (Khatt Achahid), a dissident group with several leaders established in Spain, denounces the corrupt nature of the “Polisario” “leadership” and its systematic alignment with Algeria. In addition, former “Polisario” officials have openly spoken in favor of the Moroccan proposal for advanced autonomy, asking interested parties to “respond favorably to UN Security Council resolution 1813,” inviting the parties involved in the process. The resolution of the conflict “to continue to cooperate fully with the United Nations to end the current stalemate and move towards a political solution.” They also warned against the mixed and equivocal position of the Algerian power, which they accuse of “perpetuating the status quo, by maintaining an intransigent position, which no longer hides its hegemonic visions over the region.”

Therefore, it turns out that the persistence of the conflict around the Moroccan Sahara is the result of the diktats of the Algerian officials and their inability to adapt to the evolution of the geopolitical and geo-economic situation that imposes a new vision, which must be impregnated with realism and credibility, rather than maintaining the same positions that cause the region to miss real development opportunities and further worsen an already fragile security situation in the Sahel.

“Polisario”: A threat to Peace and Security

The proliferation of extremism in the Sahel region, the precarious conditions in the Tindouf camps, as well as the anarchy and impunity that prevail there, facilitate the stagnation of “Polisario” members in illicit trafficking and their recruitment by groups of Islamist militants. This is what makes the “Polisario” today one of the most worrying threats to peace and security at the regional and international levels.

Favorable conditions for crime

According to various testimonies, the Tindouf camps, established on Algerian territory, are more akin to detention camps where the most basic human rights are violated, rather than “traditional” refugee camps. Led by an authoritarian regime that has already ruled Algeria for four decades, the camp is controlled by the armed “Polisario” militia, under the active supervision of the Algerian secret services.

Violations reported in the testimonies of people who have managed to flee from these camps or credible observers, pertain in particular to freedom of expression and association, the forced enlistment of young people or even children in the army, the separation of families, the denial of freedom of movement, forced labor, and sexual exploitation of children, to name a few. Added to this is the diversion of humanitarian aid or its deterrent work, knowing that this aid is the main source of livelihood for the population in these incorrect camps.

The “Polisario” is stuck in illicit trafficking

The authoritarianism of the “Polisario” leaders and the socio-economic structure of the “Polisario” camps based mainly on humanitarian, financial, and material aid allocated mainly by NGOs and intergovernmental organizations, have long favored the development of illicit trade and smuggling (food, drugs, cigarettes, fuel etc.). In 1999, Spanish newspaper El País revealed that €350,000 of aid from the Spanish Red Cross intended to improve the nutrition of children in the Tindouf camps had vanished. A practice that unequivocally echoes a report by the European Union prepared in 2015 by the European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF) that portrays “a system of massive diversion of humanitarian aid orchestrated by the “Polisario Front” with the complicity of Algeria.”

In addition, the geographic positioning of Tindouf in a strategic corridor between two key areas in drug trafficking from South America or Central Asia, the porosity and the length of the borders, as well as the weakness of the policing systems at the country level of the Sahelian region, encourage certain members of the “Polisario” to participate in the trafficking of arms, drugs and persons. This implication was confirmed, among other episodes, by the dismantling in 2010 by the Malian security forces fighting against trafficking of an important network called “Polisario” (a homonym of the separatist organization), because more than 90 percent of its members originate from the Tindouf camps.

The involvement of the “Polisario” in the development of terrorism

The links between “Polisario” and extremist groups operating in the region have been pointed out by various experts and demonstrated by investigations carried out by the intelligence and counterterrorism agencies.

According to Michael Braun, former director of operations of the Drug Control Agency, DEA, “powerful terrorist organizations such as Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb are experts in detecting people who show signs of vulnerability. Therefore, the Tindouf camps represent a potential gold mine for recruiters from groups like AQIM.” An ESISC report reaches the same conclusion by stating that “active members of the movement in search of additional income, as well as mercenaries who seek to profit from their past experience in the military structures of “Polisario,” may turn to terrorism after having allegedly passed through various forms of trafficking.”

As for Yonah Alexander, director of the International Center for Counter-Terrorism Studies, he underlines that “this rapprochement between certain terrorist groups in northern Mali and the young “Polisario” fighters is a logical result of the radicalization of the “Polisario” and the exacerbation of life conditions in the Tindouf camps, where populations are kidnapped against their will by separatist militias.”

Thus, faced with geopolitical developments mainly marked by the decline of the Islamic State, AQIM has always sought to develop new stratagems to adapt to changes in the situation. One of these stratagems is to support separatist movements to strengthen their presence in the region.

In this perspective, “Polisario” has been a privileged target for AQIM, despite ideological and political divergence, as evidenced by the arrest of “Polisario” elements that cooperated with this organization. This is the case of Mahjoub Mohamed Sidi, a radical Islamist from “Polisario,” arrested in 2010 in possession of a large quantity of explosives, weapons, and documents that testify to his links with AQIM officials.

In addition to AQIM, other terrorist groups will succeed in recruiting members of the “Polisario,” sometimes even for command posts. These are mainly Al-Mourabitoune, born in 2013 from the merger of the “Movement for the Singularity and Jihad in West Africa” and “Blood Signatories,” and the “Islam and Muslims Support Group,” formed in 2017 during the Mali war. Even more dangerous, Adnane Abou Walid Al-Sahraoui and his deputy Abdelkrim Al-Sahraoui, both former members of the “Polisario,” created their own terrorist group, called “Islamic State in the Greater Sahara.”

“Polisario’s” participation in terrorism was also evidenced by the Central Office for Judicial Investigation, which documented, in the course of investigations between 2008 and 2015, ties between “Polisario” members and the following terrorist cells:

- In 2008: the terrorist group Fath Al Andalous, which had planned attacks in several cities in Morocco and against members of MINURSO;

- In 2009: Al-Mourabitoune Al-Joudoud (the “New Almoravids”) a small group that aspires to establish a Caliphate in the Sahara. Its members were arrested in Laayoune and Agadir. Tapes advocating separatism were found in their possession;

- In 2010: The “Sahrawi Jihadist Front,” which had planned, among other things, the destruction of the railway that connects the Boukraâ mines with the port of Laâyoune.