Jean-Daniel Ruch is an experienced Swiss diplomat, having worked for the UN, the OSCE, and the Swiss Government between 1988 and 2023. Among his many assignments, he has served as Switzerland’s Special Envoy for the Middle East (2008-2012) and Swiss Ambassador to Serbia (2012-2016), Israel (2016-2021), and Türkiye (2021-2023). This essay does not necessarily reflect official positions of the Swiss government.

Jean-Daniel Ruch is an experienced Swiss diplomat, having worked for the UN, the OSCE, and the Swiss Government between 1988 and 2023. Among his many assignments, he has served as Switzerland’s Special Envoy for the Middle East (2008-2012) and Swiss Ambassador to Serbia (2012-2016), Israel (2016-2021), and Türkiye (2021-2023). This essay does not necessarily reflect official positions of the Swiss government.

On December 23rd, 2016, the UN Security Council adopted resolution 2334, which condemns the colonization of the occupied Palestinian territory by Israel and reaffirms the support of the international community for a two-state solution based on the 1967 borders. This is the latest move of the world’s most important governing body to embed the two-state solution into international law. The United States abstained, but did not veto the resolution. The then U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry was seen as the architect of the resolution. He had spent years working tirelessly with the Israeli government and the Palestinian Authority to make progress towards solving this long-lasting conflict, which has been a burden for any U.S. government for at least the last 35 years. George H. W. Bush was the last American president to have put serious pressure on Israel, back in the very early 1990s. In the wake of the first Gulf War, he threatened to withhold loan guarantees to Israel, should it refuse to participate in a multilateral process aimed at solving this conflict, known as the Madrid conference. Ever since, the notion of sanctioning Israel for its violations of international law has been anathema to any U.S. and most European governments.

An Israeli settlement in the West Bank, pictured near Jerusalem

Soon after the adoption of resolution 2334, the Trump Administration came to power in Washington. Under the influence of the new president’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, and his ambassador in Israel, David Friedman, himself a staunch supporter of settlements in the West Bank, Trump made bold but futile moves. He moved the American embassy to Jerusalem to please the Netanyahu government. He then proposed a peace plan, greatly departing from the one based on the 1967 borders. As was foreseen by most, the Palestinians flatly rejected the Trump proposal, and the interminable peace process was stuck once more, while the Netanyahu government accelerated the colonization enterprise, with a marked increase in settlers’ violence against Palestinians.

The Biden Administration obviously did not plan to spend much political capital in the Middle East. Ukraine and China have been the top foreign policy priorities from the outset. Biden did not reverse any of the bold Trump decisions. He did not move the U.S. Embassy back from Jerusalem to Tel Aviv. He did not reopen the U.S. consulate general to the Palestinian Authority, which has become a section of the U.S. embassy based in Jerusalem. On the other hand, the situation on the ground was relatively calm, despite a renewed 11-day exchange of rockets between Gaza and Israel in May 2021. There was a general impression that a modus vivendi had been found leading to a fragile truce, with the financial support of Qatar. On the West Bank, the Palestinian Authority was no threat to the Israeli project. And the third leg of the occupied territories, East Jerusalem, is anyway under total control of Israel. A false impression that dominated was that this choreography could continue for a very long time. The Israeli-Palestinian issue disappeared from the international agenda. Then the attacks of October 7th, 2023 happened. Both the shocking attacks and the devastating Israeli response have had an intense psychological and political impact, in addition to the dramatic human and humanitarian consequences.

The purpose of this essay is not to analyze the causes, crimes, and consequences of what happened then and in the months that followed. But, stunningly, the Palestinian issue was back at the top of the world’s agenda, on a par with the Russian aggression against Ukraine. Soon thereafter, all key international players reiterated their commitment to a two-state solution. But is it still feasible after all these years of international neglect?

A Pessimist’s View

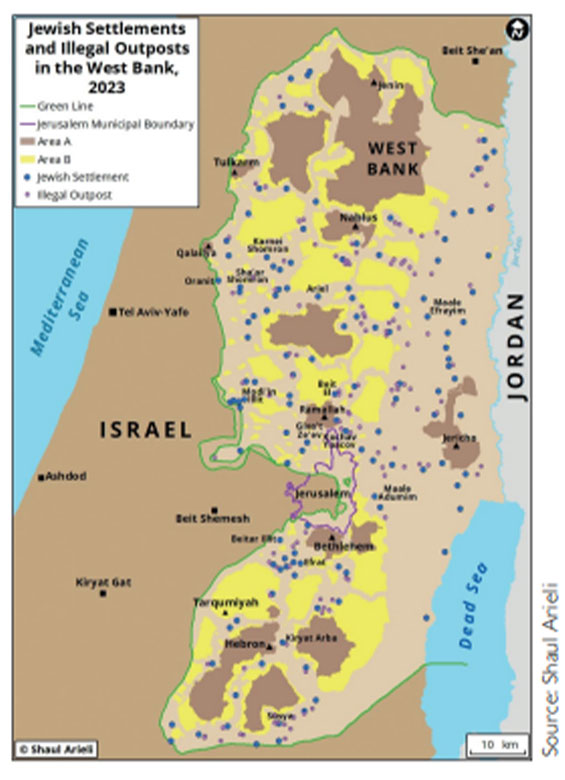

Not just the 700,000 plus settlers, but also the strategic, political, and psychological landscapes seem to be unsurmountable obstacles to any peace solution. According to reliable figures, almost 450,000 Israeli settlers live in the West Bank, and nearly 250,000 in Jerusalem.

There are a few dozen thousands more on the Golan heights, formally a Syrian territory annexed by Israel in 1981. East Jerusalem was effectively annexed in 1980. These territories, in addition to Gaza, are considered occupied under international law. The annexations and the settlements are illegal. The transfer of Israeli population to the occupied territories is prohibited by the fourth Geneva Convention and may amount to a war crime according to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. The State of Israel has played a decisive role in the colonization. It has encouraged the transfer of population by confiscating land, building infrastructure, and providing tax incentives for Israeli citizens to move their residence into the occupied territories. The proportion of “economic” settlers—meaning people who moved to the illegal settlements in East Jerusalem or the West Bank for financial or other pragmatic reasons—is diminishing compared to that of “ideological” settlers. Ideological settlers mostly believe that these lands belong to them for religious or historical reasons. Some will pretend that they were given by God to the Jewish people. The presence of Jewish shrines, for instance the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron, is enough evidence for them to claim the right to occupy those places. They refer to them as “liberated” territories. Some would agree to designate them as “disputed” territories.

On the other hand, the Palestinians stick to a strict interpretation of international law, whereby all territories occupied by Israel after the Six-Day War of 1967 must be part of a future Palestinian State. This would mean that over 700,000 settlers would have to be removed. How can this be achieved? In 2005, the Israeli government under Prime Minister Ariel Sharon removed 8,000 settlers from 21 settlements in Gaza. This became a national drama. It is hard to imagine how almost 100 times more people would be forcefully removed from the West Bank and East Jerusalem. Who would do the job?

As the proportion of settlers increases to a little less than 10 percent of the total population, this is reflected in the army and the police. And these two are supposed to be the institutions that would be tasked with evacuating the settlers, which is hardly imaginable.

Furthermore, a small but effective number of settlers are becoming more organized and also more violent. This trend has been ongoing for the past 10 years. B’Tselem, a renowned Israeli human rights NGO, has calculated that 2 million dunums of occupied land has been appropriated by Israel, which corresponds almost to the size of the state of Luxemburg. It is also reporting a steady increase in settlers’ violent incidents, including killings of Palestinians. These have increased after October 7th. On their part, the army and other security forces have not demonstrated any readiness to rein in the settlers’ violence. Quite the opposite. There are numerous reports showing security personnel just watching on while settlers harass Palestinians—or worse.

The surge in settlers’ violence is reflected in the Israeli political landscape, which has been sliding toward the far-right. By far-right, I mean the attitude of total defiance towards any withdrawal from the occupied territories and an absolute refusal to consider granting a state to the Palestinians. This extreme attitude is also rooted in the existential fear of many Israelis, who dread being outnumbered by Palestinians at some point. The rhetoric and actions of many Palestinian, Arab, or other Muslim leaders, like the Iranian regime, reinforce Israeli Jews in their belief that, without total security control over the Palestinians and strategic military superiority over the neighboring states, Israel may not survive.

The land under the control of Israel, from the Mediterranean Sea to the Dead Sea, is home to approximately the same number of Jews and of non-Jews, mostly persons who identify as Palestinians, in majority Muslims, with a small but still influential Christian minority. The October 7th events triggered a psychological shock. It has become obvious for an even larger part of the Israeli Jewish population that living side-by-side with a Palestinian State would be tantamount to sharing one’s bed with a cobra. Polls taken in the first quarter of 2024 indicate an almost full support for the eradication of Hamas, whatever the cost of innocent Palestinian lives would be. Empathy for the Palestinian civilian victims is practically non-existent. Any compromise with Hamas or the Palestinians in general would be perceived as a humiliation and a defeat threatening the very existence of the State of Israel. The determination of the Israeli public may have been further strengthened by the polls among the Palestinian population, which is showing a steady support of over 70 percent for the action undertaken by Hamas on October 7th.

Withdrawing from even one inch of the West Bank would not only be perceived as giving in to terror, but would also be seen as a major gift to Iran, a country that has been constantly presented as the arch-enemy of Israel since at least Netanyahu’s return to power in 2009. It has become suddenly obvious for everyone that, as a result of a number of strategic mistakes made by the United States and Israel over the past 20 years, Iran is now surrounding Israel from at least five fronts: Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and Gaza. U.S. President George W. Bush’s aggression against Iraq in 2003 was the single most consequential strategic mistake made by the key Israeli ally. It allowed the Islamic regime in Teheran to build a land bridge to the very border of Israel. The JCPOA, or nuclear agreement concluded by the Obama Administration in 2015 might have offered an opportunity to progressively smoothen relations between the United States and Iran, including regarding the latter’s regional influence. But Donald Trump withdrew from the agreement, with the full support of the Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Iran then continued with its encirclement maneuver around Israel, which today appears to be hostage of the Washington-Tehran dynamics.

Therefore, for practical, political, psychological, and strategic reasons, it seems highly unlikely that Israel will be ready to accept the painful compromises that a two-state solution would entail any time soon.

There should be noticeably fewer obstacles on the Palestinian side. International law, namely a solution based on the 1967 frontiers, is very much advantageous to the Palestinians. Hamas, however, has vowed to subjugate Israel so as to create a Palestinian State from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea. As an often-ignored sign of compromise, the Islamist movement issued a new document in 2017, claiming that it would be ready to consider a Palestinian State in the 1967 borders as part of a long-term truce or hudna. This position was reiterated in April 2024 during a meeting between Hamas’s leader Ismail Haniyeh and the Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan. It was even reported that Hamas would disband its armed wing should a Palestinian State be established in the 1967 borders. But Hamas is not alone in this battle. It is part of the so-called Axis of Resistance. This anti-Israeli coordination group under the leadership of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps combines the Syrian regime, Hamas, and other Palestinian militias like the Islamic Jihad, the Lebanese Hezbollah, Iraqi militias, and the Yemeni Houthis. They feel they are on the winning side of this war, and therefore under no pressure to compromise. Thus, the situation appears deadlocked.

An Optimist’s View

In 2022, Shaul Arieli, a former Israeli Colonel recognized as a top expert on settlements and settlers, published a landmark study on the settlements and the attitudes of settlers entitled “Deceptive Appearances.” He concluded that the notion that the settlements in East Jerusalem and in the West Bank have made the two-state solution impossible is a deceptive appearance and does not resist a thorough analysis. Among his main conclusions, he found that

through land swaps on a 1:1 ratio, almost 80 percent of the settlers would live within the borders of Israel following a peace accord;

among the 20 percent remaining in what would then be a Palestinian State, a large majority would be ready to consider relocating to Israel provided compensations are offered;

within the same group, only a very tiny portion would resort to unlawful acts of resistance, whereas the vast majority would consider only lawful opposition.

an immense majority of the settlers are aware of the risk that they may one day be asked to relocate within the Israeli border.

Furthermore, the study finds that the three goals defined by the Israeli governments that planned the settlement enterprise (Allon Plan, 1967; Sharon Plan, 1977) have not been secured, namely:

to encircle any Arab political entity with Israeli territories, delineating a border reflecting Israeli priorities;

to prevent the establishment of an independent Palestinian State with territorial continuity by ensuring a substantial Israeli presence, particularly along the central mountain ridge;

to annex all or significant parts of the occupied territories to the State of Israel without impairing the Zionist vision of a democratic state with a Jewish majority.

Today, Jewish settlers comprise only 14 percent of the population of the West Bank (a territory referred to as Judea and Samaria by Israelis). As mentioned above, close to 80 percent of that group would find itself in Israel following land swaps whereby the same surface of land would be exchanged between the Israeli and Palestinian States along the following proposal:

Among the 20 percent that would remain to be evacuated, approximately 100,000 people, or 20 to 25,000 households, only a tiny fraction is ready to fight a two-state solution through illegal means, whereby most of them would accept to relocate following compensations.

Common sense would imply that the ferocious outburst of violence that occurred on October 7th and its aftermath created even higher psychological and political barriers preventing any resumption of negotiations between Israeli and Palestinians. However, this may not be the case. Even though a vast majority of the Israeli public supports the destruction of Hamas whatever the human costs, a brutal awakening took place after the October 7th attacks. The awareness that the Palestinian issue cannot be ignored anymore has grown in society. The eternal management of the conflict is not a desirable option for an increased number of Israeli Jews. Polls from the first quarter of 2024 indicate that, after the initial shock, there is a trend in favor of a two-state solution. Within the Palestinian population, the support is at 45 percent and growing. In Israel, 35 percent of the Jewish population expressed support for this option, meaning 40 percent of the overall population. Interestingly, when combined with normalization with Saudi Arabia, the figure increases to 52 percent.

Adding to this psychological climate, the desire for separation is much stronger now than before October 7th. Therefore, there is a readiness to also pay the price of evacuating settlements. More than 100,000 Israelis have left their homes in Northern Galilea and the vicinity of Gaza after the attack. Relocation is no longer seen as an unsurmountable obstacle. On the Palestinian side, there are also more voices today who dare to accuse Hamas of being responsible of the humanitarian disaster that resulted from the Israeli retaliation.

That being said, coming out of this tragedy will require political leadership. One can hardly imagine Benjamin Netanyahu sitting with Mahmoud Abbas—let alone Ismail Haniyeh or Yahya Sinwar—to discuss an end to the conflict. On the Palestinian side, one might expect that Hamas will be seriously weakened, both politically and militarily, after the conflict. There will be a unique chance to refresh the Palestinian leadership under a single government. This is long overdue. Since 2007, the split between Gaza and the West Bank has been a major impediment to any serious effort towards peace. On the Israeli side, the massive demonstrations and the polls show that there is a fair chance that Netanyahu will be out of office soon after the war’s end. Some experts suspect this may be one of the reasons why Israel has steadily tried to provoke Iran into a regional escalation. Those best placed to succeed the longest-serving prime minister in the history of Israel would all be better prepared to find an arrangement with the Palestinians. Of course, there is still a tiny possibility that the hawks in Israel, like Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich and National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir, might maintain positions of power. Their policies can only lead to more bloodshed. This is where the international community should play a decisive role.

As noted above, all major international actors, including the United States, China, Russia, and European powers have underlined that there is no alternative to the two-state solution. In the United States in particular, there is less and less understanding for the sitting Israeli Prime Minister and his policies. This is also true in several European countries, especially Spain and Ireland. For a very long time, Western countries were reluctant to put real pressure on Israel. Such tolerance is now rapidly diminishing.

A Realist’s View

Common sense dictates that to bring peace to the Middle East, three factors must be aligned: an Israeli Prime Minister strong enough to make compromises; a Palestinian leader capable of uniting the various Palestinian factions; and an American President ready to use his or her political capital to massage the two communities into a deal. The war has caused immense trauma and suffering within the Israeli and Palestinian populations. A return to the status quo ante is unlikely. Worse, it would be another missed opportunity with possibly even more tragic consequences.

The examples throughout this essay demonstrate that a two-state solution remains technically feasible. Psychologically, both societies, as polls reveal, seem to understand the necessity for their mere survival to move beyond conflict. Palestinians have enough reason to fear that Israeli policies will further shrink the space in which they can live. On the other hand, Israeli Jews have just as relevant reasons to be afraid of someday being overwhelmed by their neighbors. After all, isn’t Iran, directly or through its proxies, now present on five of its borders? The Iranian retaliation against Israeli territory in mid-April, following an earlier Israeli attack against the Iranian consulate in Damascus, gives a taste of the cost of regional escalation. Israel and its allies would have had to spend over one billion dollars to protect against the incoming Iranian missiles and drones just on that single attack. Can a regional escalation be prevented unless a meaningful political process is put on track? What are the alternatives to a two-state solution? Ethnic cleansing one way or the other? A regional war involving the United States and Iran, in which the latter would most probably receive significant Russian support? The amount of destruction would be unthinkable and can’t be in the interest of anyone.

On the other hand, a lot of preparatory work has been done to shape a two-state solution. The Clinton Parameters (2000), but also the results of the Olmert-Abbas talks (2008), remain sound bases for an arrangement. But probably the most detailed blueprint is the achievement of Israeli and Palestinian experts who were parts of both negotiating teams in the Clinton years. They have designed a 500-page model agreement, often known as the Geneva Accord. From this and other documents, it appears not only that a peace is possible, but also that it entails significantly less costs than any other option. There would be land swaps on a 1:1 ratio to bring as many settlers as possible within Israeli borders. Palestine would be a demilitarized state, and a strong security coordination under international supervision would be established between the two states. On the other hand, Palestine would be given a territorial continuity through a land corridor connecting the West Bank and Gaza. East Jerusalem would be the capital of Palestine, and a special regime would be agreed upon for Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif. The thorny issue of the Palestinian refugees would be solved mainly through financial compensations. Israel would not be flooded by millions of Palestinian refugees, as is sometimes threatened by those who are not interested in a compromise.

There are other solutions being discussed, like a confederation or a binational state. However, none of these would avoid having to deal with the thorny issues mentioned in the previous sections. But, whereas technically a two-state solution remains possible, it is doubtful whether the great powers would be able to provide the colossal amount of political investment required to evacuate the spoilers from the equation.

This is probably the biggest challenge: weakening the extremes. On the Israeli side, the forces opposing a two-state solution need to be isolated politically. Those settlers involved in violence against Palestinians in the West Bank and Jerusalem must be punished for their crimes. The Western countries must be principled and insist that without an end to impunity, there will be consequences. Defusing the spoilers on the Palestinian side may be trickier. Hamas and other violent factions may be weakened; they will probably not disappear. There is no clear path towards a new governance system ruling over both the West Bank and Gaza—and East Jerusalem in due time. Is imposing a government selected by Arab States, with the consent of the United States and Israel, the right approach? On the other hand, elections might bring back Hamas, which remains more popular than Abbas’s Fatah, like in 2006. Would Israel and the West this time be ready to do what they refused to do almost twenty years ago, namely recognize as legitimate a government run by an Islamist movement? This would require a revolution in their policies.

At the end of the day, regional dynamics will play a crucial role. Building on the so-called Abraham accords, and the normalization of relations between Teheran and Riyadh achieved in Beijing in 2023, a virtuous cycle could be encouraged between Israel, the various Palestinian factions, and the regional powers. The Arab Peace Initiative, put forward by the Saudi king in 2002, remains valid. It offers peace with all Arab countries in exchange for an end to the occupation. Throughout the Gaza war, Washington and Teheran have been striving to avoid a regional escalation. Even the Iranian attack against Israeli territory on April 14th, 2024, was carefully calibrated with the stated intention to avoid an uncontrollable escalation. Could this prelude the resumption of a more constructive approach by the key players?

Reining in on spoilers while offering incentives would also require that, after a long, long time, Washington, Beijing, and Moscow would accept to work together—or at least not disrupt the efforts of one of the other powers. Are they ready to cooperate on the Middle East despite their global competition and confrontation on issues like Ukraine and Taiwan? It should be clear to everyone that the benefits of cooperating to bring about a two-states solution vastly outweigh its costs. This would usher in a new era that would benefit all people in the region—and ultimately, the world.

A two-state solution remains desirable and is technically feasible. However, the psychological and political hurdles are huge. And the political will required to make brave and risky investments for the sake of genuine peace prospects is not nearly as significant as it should be.