László Vasa is a Chief Advisor and Senior Research Fellow at the Hungarian Institute of International Affairs, as well as a Professor at the Széchenyi István University, Hungary.

László Vasa is a Chief Advisor and Senior Research Fellow at the Hungarian Institute of International Affairs, as well as a Professor at the Széchenyi István University, Hungary.

Iran is home to a diverse socio-cultural environment, as shown by the fact that around 50 percent of the country’s population is of non-Persian background. On the other hand, academics often use the words Persians and Iranians interchangeably, thereby neglecting the fact that the term Iranian has a broader meaning that encompasses a vast number of individuals of other ethnicities living in the Islamic Republic. It is estimated that around one-third of the population in Iran consists of Azerbaijanis, making them the most significant ethnic minority group. Some of the other significant ethnic groups that may be found all over the globe are the Turkmen, Arabs, Baluchis, and Kurds.

A substantial number of people of non-Persian origin live in the country’s border regions, and they continue to maintain connections with their fellow ethnic groups in neighboring countries like Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Pakistan, and Iraq. Events that take place outside of Iran’s boundaries have a significant influence on the different ethnic groups that exist in the territory of the country, as these minorities are very sensitive to influence and manipulation.

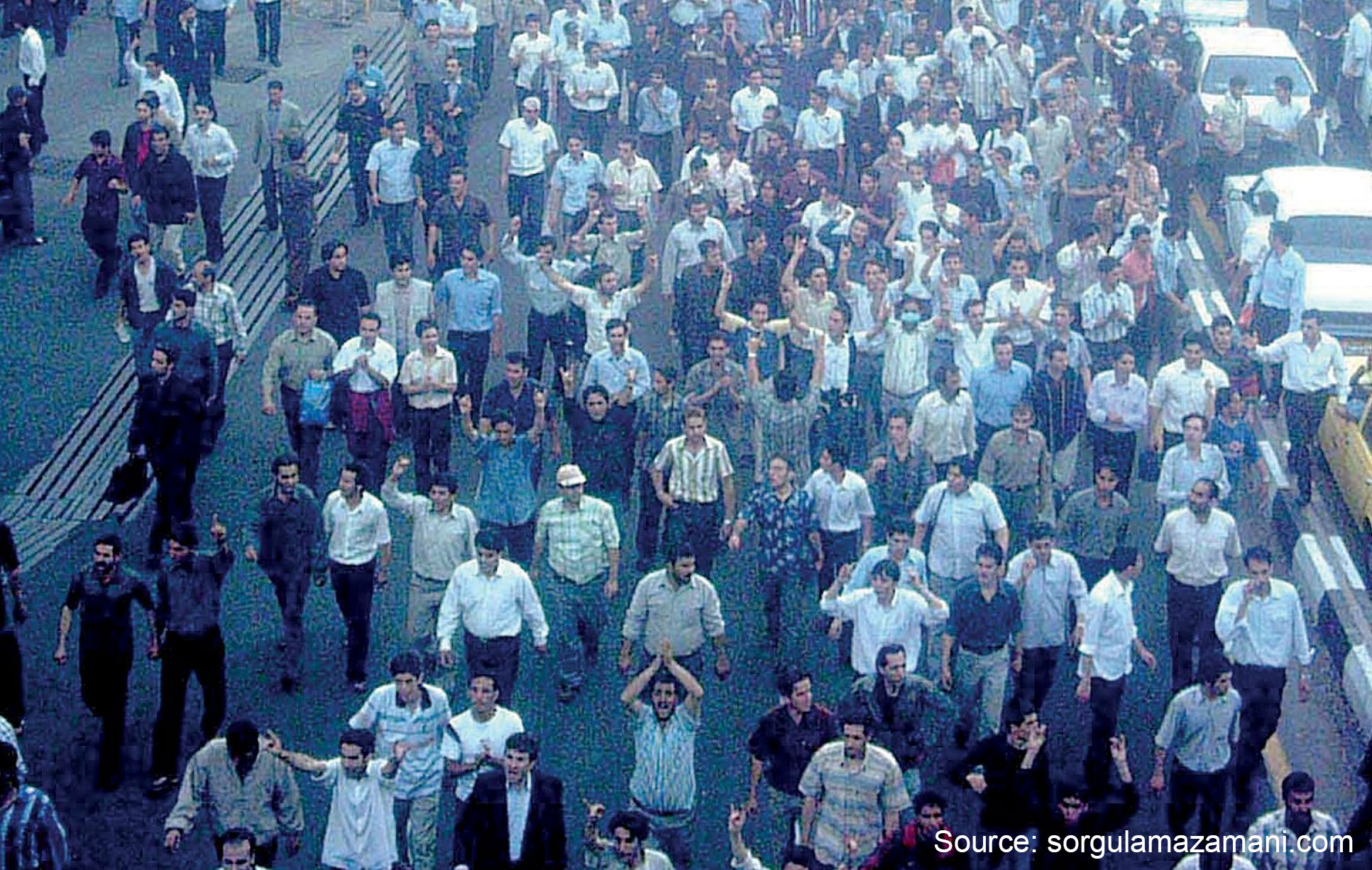

The 2006 Azerbaijani protests in Iran following the newspaper cartoon controversy

In the South Caucasus and the Caspian Sea region, Russia and Iran were formerly engaged in two major wars as a result of their competition for dominance and influence. Both conflicts were fought in the region. They were ended by the treaties of Gulistan, signed on October 12th, 1813, and Turkmenchay, signed on February 10th, 1828, respectively. Following the end of the second Russo-Persian war, the Russian Empire and Iran executed a legal division of Azerbaijan into two sections: the northern and the southern region. The southern Azerbaijan region has therefore evolved into an important space within Iran. The people of Southern and Northern Azerbaijan have the same ethnic identity, despite the fact that they have been separated from one another for more than 150 years, both in terms of geography and culture.

East Azerbaijan Province, West Azerbaijan Province, and Ardabil Province are three territories of Iran situated in close proximity to the Republic of Azerbaijan, each with a population that mostly consists of Azerbaijani people. Many individuals from Azerbaijan often use the term “South Azerbaijan” to refer to the majority of the territory in Iran’s northwest.

The Persian language finally became an essential weapon for national unity in Iran, progressively overshadowing the widespread multilingualism that had long existed within society. This began when the Pahlavi dynasty first came to power in Iran in 1925, and continued with the emphasis on nationalism that led up to the ending of the Ottoman period. Because of the attitude towards them, the Turkish-speaking population—along with members of other ethnic groups—was denied the opportunity to obtain formal education in their mother tongue. Since the 1979 Islamic revolution, inhabitants of Iran’s Azerbaijani provinces have been granted permission to read some publications and listen to radio broadcasts in Turkish. In spite of this, the Iranian leadership has shown an increasing degree of concern regarding the spread of irredentist inclinations, even after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

In Iran, throughout both ruling periods of the Pahlavi dynasty (1921–1979) and the Islamic Republic (since 1979), cultural rights and political activities of ethnic minorities have been significantly restricted. These restrictions remained in place for a substantial amount of time. Much of the mainstream research conducted on the social and political framework of Iran demonstrates a tendency to underestimate the significance of ethnicities. For instance, it is very common to refer to Azerbaijanis, who constitute the largest ethnic minority group in Iran, as a “well-integrated minority” with a limited “sense of distinct identity.” This is often done to project an image that Azerbaijanis have assimilated into the culture of Iran.

Despite efforts to promote a rosy picture of voluntary assimilation, the Iranian authorities have pursued policies that resulted in substantial numbers of Iranian Azerbaijanis fleeing the country. The United States, Türkiye, Russia, the Republic of Azerbaijan, and many EU members states have experienced a considerable increase in the number of people migrating to their countries. Over eight million Iranian Azerbaijanis are now estimated to live outside Southern Azerbaijan. More than a million of them are regarded as political immigrants, living in either Europe or the United States. Additionally, there are some individuals who have migrated from the provinces of Azerbaijan to other areas within Iran, most notably the capital, Tehran. The percentage of Azerbaijani immigrants and their descendants from the first or second generation is estimated to be somewhere between 25 and 33 percent of the entire population of Tehran’s metropolitan area. The Iranian government has violated the rights of the Azerbaijani population, including their rights to be a minority, as well as those to cultural and linguistic expression, and national identity. An assimilation program has been launched by the central government of Iran in an attempt to halt the spread of certain groups and to maintain tight control over the pace of population growth.

The central government of Iran habitually breaches minority population rights in a range of realms, including in the political, financial, and religious spheres. These violations occur in a variety of circumstances. Because they have a non-Persian national identity and make up a large portion of the country’s population, the Iranian government has been discriminating against Azerbaijanis since the 1990s. In general, the political ties between the central government of Iran and the country’s minorities are famously unstable. Following the establishment of the independent Republic of Azerbaijan in 1991, the national identity of the Azerbaijani people has only strengthened.

Both the Pahlavi dynasty and the theocratic government that assumed power in 1979 have a record of consistent discrimination against South Azerbaijanis based on their ethnicity. This discrimination has occurred on several occasions. Over a long period of time, ethnic Azerbaijanis have been subjected to assimilation tactics, negative stereotypes, and forced relocation, all of which have contributed to their marginalization within society. The people who live in Southern Azerbaijan are now being subjected to a number of strategies aimed at suppressing their language, culture, and traditions. Despite the fact that Iranian laws provide minorities with the explicit right to speak their own language, the central government of Iran places significant restrictions on the use of the Azerbaijani language in educational institutions. The persistent practice of Persianizing the Southern Azerbaijani toponyms provides reason for concern, as it represents an intentional effort to usurp a cultural identity with the ultimate goal of cultural appropriation. In addition to disregarding cultural history of Azerbaijan, Iran’s actions also carry the potential to inflict real damage under some circumstances. One such example is the destruction of the Ark Castle in Tabriz, which was partially demolished by the regime. The bombing that took place was intended to clear the space for future construction.

Following the death of Mahsa Amini in September 2022, a Kurdish-Iranian woman who is suspected to have died as a result of police brutality for refusing to wear a hijab, nationwide protests erupted in Iran. This, in turn, led to a further deterioration of the Kurdish position within the country. Outcries such as “Freedom, Justice, and National Government” were heard from a few demonstrators, indicating that they called for reform of the Islamic Republic. Subsequently, the political, social, and economic grievances against legislation that would make the wearing of the hijab mandatory became more prevalent in the protests. In order to put an end to the rallies, the Iranian authorities decided to utilize the entire security apparatus, including in the provinces of Southern Azerbaijan. The findings of an in-depth study by a group of specialists indicate that the crackdown was very oppressive. During the first two weeks of the protests, the number of persons who were detained in Tabriz—the most important city in South Azerbaijan—surpassed 1,700. Furthermore, during the government raids that took place in the area between September and December 2022, the security forces shot and injured at least 24 individuals, resulting in just as many deaths. Over the course of the same time period, hundreds of additional demonstrators incurred injuries. At least six individuals of Azerbaijani descent have since been found guilty and sentenced to death.

There has been much discussion in the international media about political unrest and widespread protest movements in Iran since the aforementioned events. Although the anti-regime protests in Iran have taken on a broad character and engulfed many parts of the country for months on end, many analysts take note of the ethnic dimensions of the protests.

Much of the international analysis tends to focus on instability and violence resulting from the Iranian regime’s clashes with ethnic Kurds, or Iran’s Baluch minorities. Less attention has been devoted to the plight of the country’s Azerbaijani communities, who make up tens of millions and are located mostly in Iran’s provinces bordering Azerbaijan. This is somewhat surprising. The momentum of unrest involving Iran’s ethnic Azerbaijanis has been on the rise.

However, few present-day analysts recall the May 2006 events of Khordad, or ‘National Day of Mutiny.’ Those events, while relatively unknown in the West, are reflective of the largest and most turbulent protests of ethnic Azerbaijani communities to have ever taken place in the Islamic Republic. So significant were the protests that rocked Iran’s South Azerbaijan (Zanjan, Tabriz, Urmia, Ardabil) in 2006, that some activists now refer to these events as the ‘Day of National Awakening’ of ethnic Azerbaijani communities in Iran.

The protests were sparked by an offensive caricature published on May 12th, 2006, by pro-regime Iran-e-jomee newspaper. This news item caused massive offence to ethnic Azerbaijani communities, while the publication was most likely intended as a provocation. It was published in the children’s section of the newspaper, comparing Azerbaijani communities in Iran with cockroaches. Fierce protests erupted, lasting for some two weeks.

As the violence and tensions spiraled, the regime-backed media outlet responsible for the publication appeared to backtrack, possibly to appease the protesters. On May 21st, 2006, the newspaper issued an apology, whilst the editor-in-chief and cartoonists responsible for the caricature—Mehrdad Ghasemfar and Mana Neyestani—were both arrested. By that time, however, substantial damage had already been done. Violence continued. The government admitted that there were casualties, claiming that four protestors were killed and another 330 detained by the authorities. Amnesty International has pointed to a much higher number, estimating that up to several thousand ethnic Azerbaijanis were jailed or killed. Azerbaijani community activists in Iran claimed that more than 5,000 activists were detained and even tortured, with up to 150 killed. Some were reportedly killed by methods too violent to be described in this article.

Whatever the final number of victims, it is clear that ethnic Azerbaijani communities in Iran and their compatriots all over the world every year mark May 22nd (I Khordad on the Iranian calendar) as the day to remember those who died in the protests. Commemorative events have been taking place in Azerbaijani communities around the world ever since. In May 2023, large-scale commemorative rallies honoring the victims of Khordad were staged in Berlin. The German capital became the focal point for remembrance processions for ethnic Azerbaijani communities in Europe. Thousands of Azerbaijanis gathered in front of Berlin’s symbolic Brandenburg Gates to protest policies of ethnic discrimination and oppression orchestrated by the Iranian regime, and to demand equal rights for their community in Iran.

The swathes of protesters, many of whom are originally from Iran, called for freedom and justice for their compatriots still living inside the Islamic Republic. Many waved Azerbaijani flags and were adorned by symbolic slogans reflecting their ethnic Azerbaijani identity, many of which are currently banned by the Iranian authorities. It is high time that the international community recognizes the long struggle of Azerbaijani communities in Iran. Commemorative events remembering Khordad will only become bigger and more prominent in the future.

Both the political side of the Southern Azerbaijani movement and the administrative machinery of the Iranian government are equally exposed to these repressions. As many international organizations, including Amnesty International, have recorded, the Iranian regime frequently resorts to arresting a substantial number of individuals during cultural events and protests in Azerbaijan. The efforts of Azerbaijani activists to promote political and cultural rights of Southern Azerbaijanis have resulted in a considerable number of activists being imprisoned, facing torture, and/or forced into exile on an annual basis.

It is quite easy to imagine that the ongoing struggle of Southern Azerbaijanis—and the repression they are subjected to—will continue not to receive nearly enough attention from the international community. This runs in stark contrast to a multitude of other crises involving Iran and the Middle East. To reverse this negative trend, it is essential that Azerbaijani communities keep reminding the international public of their cause and do so in a variety of geographical and thematic settings.