Jerome C. Glenn is the CEO of The Millennium Project, Chairman of the AGI Panel of the UN Council of Presidents of the General Assembly, and author of the forthcoming book Global Governance of the Transition to Artificial General Intelligence (2025).

Jerome C. Glenn is the CEO of The Millennium Project, Chairman of the AGI Panel of the UN Council of Presidents of the General Assembly, and author of the forthcoming book Global Governance of the Transition to Artificial General Intelligence (2025).

The international conversation on AI is often terribly confusing, since different kinds of AI become fused under the one overarching term. There are three kinds of AI: narrow, general, and super AI, with some grey areas in between. It is very important to clarify these distinctions because each type has very different impacts and vastly different national and international regulatory requirements.

Without national and international regulation, it is inevitable that humanity will lose control of what will become a non-biological intelligence beyond our understanding, awareness, and control. Half of AI researchers surveyed by the Center for Human Technology believe there is a 10 percent or greater chance that humans will go extinct from their inability to control AI. But, if managed well, artificial general intelligence could usher in great advances in the human condition—from medicine, education, longevity, and turning around global warming to advances in scientific understanding of reality and creating a more peaceful world. So, what should policymakers know and do now to achieve the extraordinary benefits while avoiding catastrophic, if not existential, risks? First of all, it is important to understand the different kinds of AI.

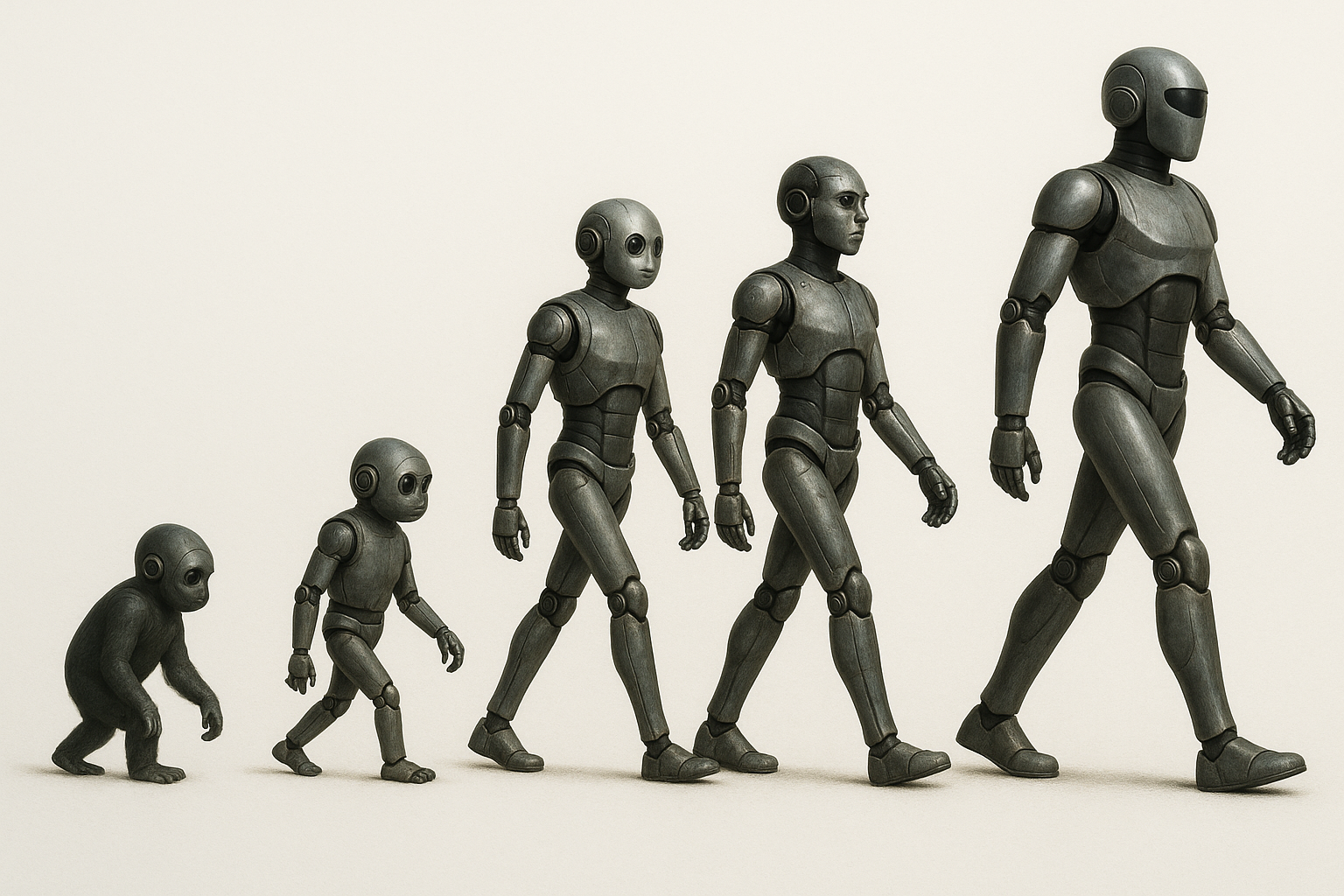

A creative illustration of AI’s evolution, a process that is certain to escape human control | Source: ChatGPT

Artificial narrow intelligence (ANI) ranges from tools with limited purposes, such as diagnosing cancer or driving a car, to the rapidly advancing generative AI that answers many questions, generates software code, pictures, movies, and music, and summarizes reports. In the grey area between narrow and general are AI agents and general-purpose AI becoming popular in 2025. For example, AI agents can break down a question into a series of logical steps. Then, after reviewing the user’s prior behavior, the AI agent can adjust the answer to the user’s style. If the answers or actions do not completely match the requirements, then the AI agent can ask the user for more information and feedback as necessary. After the completed task, the interactions can be updated in the AI’s knowledge base to better serve the user in the future.

Artificial general intelligence (AGI) does not exist at the time of this writing. Many AGI experts believe it could be achieved or emerge as an autonomous system within five years. It would be able to learn, edit its code to become recursively more intelligent, conduct abstract reasoning, and act autonomously to address many novel problems with novel solutions similar to or beyond human abilities. For example, given an objective, it can query data sources, call humans on the phone, and rewrite its own code to create capabilities to achieve the objective as necessary. Although some expect it will be a non-biological sentient, self-conscious being, it will at least act as if it were, and humans will treat it as such.

Artificial super intelligence (ASI) will be far more intelligent than AGI and likely to be more intelligent than all of humanity combined. It would set its own goals and act independently from human control and in ways that are beyond human understanding and awareness. This is what Bill Gates, Elon Musk, and the late Stephen Hawking have warned us about and what some science fiction has illustrated for years. Humanity has never faced a greater intelligence than its own.

In the past, technological risks were primarily caused by human misuse. AGI is fundamentally different. Although it poses risks stemming from human misuse, it also poses potential threats caused by AGI. As a result, in addition to the control of human misuse of AI, regulations also have to be created for the independent action of AGI. Without regulations for the transition to AGI, we are at the mercy of future non-biological intelligent species.

Today, there is a competitive rush to develop AGI without adequate safety measures. As Russian President Vladimir Putin famously warned about AI development, “the one who becomes the leader in this sphere will be the ruler of the world.”

So far, there is nothing standing in the way to stop an increasing concentration of power, the likes of which the world has never known.

Nations and corporations are prioritizing speed over security, undermining potential national governing frameworks, and making safety protocols secondary to economic or military advantage. There is also the view that Company A might feel a moral responsibility to get to AGI first to prevent Company B, because Company A believes they are more responsible than Company B. If Company B, C, and D have the same beliefs as Company A, then each company believes it has a moral responsibility to accelerate their race to achieve AGI first. As a result, all might cut corners along the way to become the first to achieve this goal, leading to dangerous situations. The same applies to the national military development of AGI.

Since many forms of AGI from governments and corporations are expected to emerge before the end of this decade—and since establishing national and international governance systems will take years—it is urgent to initiate the necessary procedures to prevent the following outcomes of unregulated AGI, documented for the UN Council of Presidents of the General Assembly:

Irreversible Consequences. Once AGI is achieved, its impact may be irreversible. With many frontier forms of AI already showing deceptive and self-preserving behavior, and the push toward more autonomous, interacting, self-improving AIs integrated with infrastructures, the impacts and trajectory of AGI can plausibly end up being uncontrollable. If that happens, there may be no way to return to a state of reliable human oversight. Proactive governance is essential to ensure that AGI will not cross red lines, leading to uncontrollable systems with no clear way to return to human control.

Weapons of mass destruction. AGI could enable some states and malicious non-state actors to build chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear weapons. Moreover, large AGI-controlled swarms of lethal autonomous weapons could themselves constitute a new category of WMDs.

Critical infrastructure vulnerabilities. Critical national systems (e.g., energy grids, financial systems, transportation networks, communication infrastructure, and healthcare systems) could be subject to powerful cyberattacks launched by or with the aid of AGI. Without national deterrence and international coordination, malicious non-state actors—from terrorists to transnational organized crime—could conduct attacks at a large scale.

Power concentration, global inequality, and instability. Uncontrolled AGI development and usage could exacerbate wealth and power disparities on an unprecedented scale. If AGI remains in the hands of few nations, corporations, or elite groups, it could entrench economic dominance and create global monopolies over intelligence, innovation, and industrial production. This could lead to massive unemployment, widespread disempowerment affecting legal underpinnings, loss of privacy, and collapse of trust in institutions, scientific knowledge, and governance. It could undermine democratic institutions through persuasion, manipulation, and AI-generated propaganda, and heighten geopolitical instability in ways that increase systemic vulnerabilities. A lack of coordination could result in conflicts over AGI resources, capabilities, or control, potentially escalating into warfare. AGI will stress existing legal frameworks: many new and complex issues of intellectual property, liability, human rights, and sovereignty could overwhelm domestic and international legal systems.

Existential risks. AGI could be misused to create mass harm or developed in ways that are misaligned with human values. Furthermore, it could even act autonomously beyond human oversight, evolving its own objectives according to self-preservation goals already observed in current frontier AIs. AGI might also seek power as a means to ensure it can execute whatever objectives it determines, regardless of human intervention. National governments, leading experts, and the companies developing AGI have all stated that these trends could lead to scenarios in which AGI systems seek to overpower humans. These are not far-fetched science fiction hypotheticals about the distant future—many leading experts fear that these risks could all materialize within this decade, and their precursors are already occurring. Moreover, leading AI developers have thus far had no viable proposals for preventing these risks.

Loss of extraordinary future benefits for all of humanity. Properly managed AGI promises improvements in all fields, for all peoples—from personalized medicine, curing cancer, and cell regeneration, to individualized learning systems, ending poverty, addressing climate change, and accelerating scientific discoveries with unimaginable benefits. Ensuring such a magnificent future for all requires global governance, which begins with improved global awareness of both the risks and benefits. The United Nations is critical to this mission.

Although we may not be able to directly control how ASI emerges and acts, we can create national and international regulations for how AGI is created, licensed, used, and governed before it accelerates its learning and emerges into ASI beyond our control. We can explore how to manage the transition from ANI to AGI. How well we manage that transition is likely to also shape the transition from AGI to ASI.

We can think of ANI as our young children, whom we control—what they wear, when they sleep, and what they eat. We can think of AGI as our teenagers, over whom we have some control, which does not include what they wear or eat or when they sleep.

And we can think of ASI as an adult, over whom we no longer have any control. Parents know that if they want to shape their children into good, moral adults, then they have to focus on the transition from childhood to adolescence. Similarly, if we want to shape ASI, then we have to focus on the transition from ANI to AGI. And that time is now.

The greatest research and development investments in history are now focused on creating AGI.

Without national and international regulations for AGI, many AGIs from many governments and corporations could continually re-write their own codes, interact with each other, and give birth to many new forms of artificial superintelligences beyond our control, understanding, and awareness.

Governing AGI is the most complex, difficult management problem humanity has ever faced. To help understand how to accomplish safer development of AGI, The Millennium Project, a global participatory think tank, conducted an international assessment of the issues and potential governance approaches for the transition from today’s ANI to future forms of AGI. The study began by posing a list of 22 AGI-critical questions to 55 AGI experts and thought leaders from the United States, China, United Kingdom, Canada, EU, and Russia. Drawing on their answers, a list of potential regulations and global governance models for the safe emergence and governance of AGI was created. These, in turn, were rated by an international panel of 299 futurists, diplomats, international lawyers, philosophers, scientists, and other experts from 47 countries. The results are available in State of the Future 20.0 from www.millennium-project.org.

In addition to the need for governments to create national licensing systems for AGI, the United Nations has to provide international coordination, critical for the safe development and use of AGI for the benefit of all humanity. The UN General Assembly has adopted two resolutions on AI: 1) the U.S.-initiated resolution “Seizing the opportunities of safe, secure, and trustworthy artificial intelligence systems for sustainable development” (A/78/L.49); and 2) the China-initiated resolution “Enhancing international cooperation on capacity-building of artificial intelligence” (A/78/L.86). These are both good beginnings but do not address managing AGI. The UN Pact for the Future, the Global Digital Compact, and UNESCO’s Recommendation on the Ethics of AI call for international cooperation to develop beneficial AI for all humanity, while proactively managing global risks. These initiatives have brought world attention to current forms of AI, but not AGI. To increase world political leaders’ awareness of the coming issues of AGI, a UN General Assembly special session specifically on AGI should be conducted as soon as possible. This will help raise awareness and educate world leaders on the risks and benefits of AGI and why national and global actions are urgently needed.

The following items should be considered during a UN General Assembly session specifically on AGI:

A global AGI observatory is needed to track progress in AGI-relevant research and development and provide early warnings on AI security to UN member states. This observatory should leverage the expertise of other UN efforts, such as the Independent International Scientific Panel on AI, created by the Global Digital Compact and the UNESCO Readiness Assessment Methodology.

An international system of best practices and certification for secure and trustworthy AGI is needed to identify the most effective strategies and provide certification for AGI security, development, and usage. Verification of AGI alignment with human values, controlled and non-deceptive behavior, and secure development is essential for international trust.

A UN Framework Convention on AGI is needed to establish shared objectives and flexible protocols to manage AGI risks and ensure equitable global benefit distribution. It should define clear risk tiers requiring proportionate international action, from standard-setting and licensing regimes to joint research facilities for higher-risk AGI, and red lines or tripwires on AGI development. A UN Convention would provide the adaptable institutional foundation essential for globally legitimate, inclusive, and effective AGI governance, minimizing global risks and maximizing global prosperity from AGI.

Another necessary step would be to conduct a feasibility study on a UN AGI agency. Given the breadth of measures required to prepare for AGI and the urgency of the issue, steps are needed to investigate the feasibility of a UN agency on AGI, ideally in an expedited process. Something like the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has been suggested, understanding that AGI governance is far more complex than nuclear energy; and hence, such an agency will require unique considerations in such a feasibility study. Uranium cannot re-write its own atomic code, it is not smarter than humans, and we understand how nuclear reactions occur. Hence, management of atomic energy is much simpler than managing AGI.

Some have argued that the UN and national AI governance is premature and that it would stop innovations necessary to bring great benefits to humanity. They argue that it would be premature to call for establishing new UN governance mechanisms without a clearer understanding and consensus on where there may be gaps in the ability of existing UN agencies to address AI; hence, any proposals for new processes, panels, funds, partnerships, and/or mechanisms are premature. This is short-sighted.

National AGI licensing systems and a UN multi-stakeholder AGI agency might take years to create and implement. In the meantime, there is nothing stopping innovations and the great AGI race. If we approach establishing national and international governance of AGI in a business-as-usual fashion, then it is possible that many future forms of AGI and ASI will be permeating the Internet, making future attempts at regulations irrelevant.

The coming dangers of global warming have been known for decades, yet there is still no international system to turn around this looming disaster. It takes years to design, accept, and implement international agreements. Since global governance of AGI is so complex and difficult to achieve, the sooner we start working on it, the better.

Eric Schmidt, former CEO of Google, has said that the “San Francisco Consensus” is that AGI will be achieved in three to five years. Elon Musk, who normally opposes government regulation, has said future AI is different and has to be regulated. He points out that we don’t let people go to a grocery store and buy a nuclear weapon. For over ten years, Musk has advocated for national and international regulations of future forms of AI. If national licensing systems and a UN AGI agency have to be in place before AGI is released on the Internet, then political leadership will have to act with expediency never before witnessed. This cannot be a business-as-usual effort. Geoffrey Hinton, one of the fathers of AI, has said that such regulation may be impossible, but we have to try. During the Cold War, it was widely believed that nuclear World War III was inevitable and impossible to prevent. The shared fear of an out-of-control nuclear arms race led to agreements to manage it. Similarly, the shared fear of an out-of-control AGI race should lead to agreements capable of managing that race.