Yerzhan Saltybayev is Director of the Institute of World Economy and Politics at the Foundation of the First President of the Republic of Kazakhstan.

Yerzhan Saltybayev is Director of the Institute of World Economy and Politics at the Foundation of the First President of the Republic of Kazakhstan.

China is currently one of the major drivers of the world economy. Its contribution to global economic growth in recent years has consistently exceeded 30 percent, despite the relative slowdown in rates. Moreover, China’s economic weight is growing, as evidenced by the country’s increased share of global GDP (from 1.2 percent in 1979 to 15.2 percent in 2017).

It has become clear that, provided China continues to pursue a policy aimed at attaining global economic leadership, it stands every chance of surpassing the United States and becoming the world’s largest economy in the next 10 years.

In turn, the growing financial and economic power of the country inevitably impacts on its foreign policy. The 19th Congress of the Communist Party of the People’s Republic of China, held in October 2017, is noted for policy statements asserting that China should play a more proactive role on the world stage.

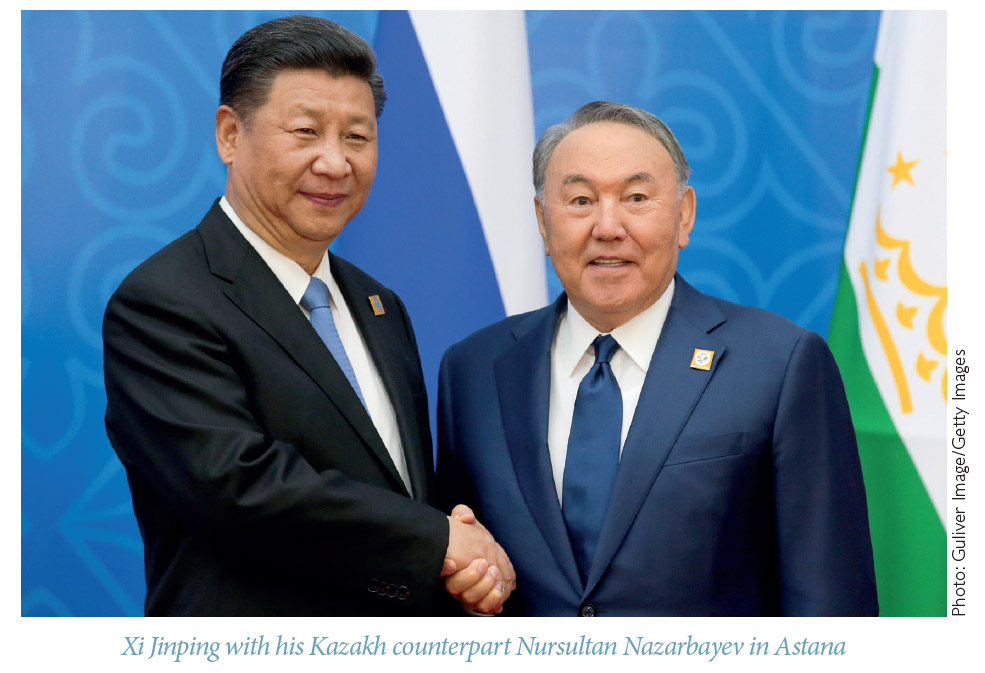

The most vivid expression of China’s changing geopolitical positioning is undoubtedly the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which was first announced in 2013 by President Xi Jinping in Kazakhstan’s capital, Astana. Ambitious in every sense of the word, the project envisions China’s implementation of large-scale infrastructure projects on at least three continents, costing a total amount of more than $900 billion. In this regard, it is quite natural for BRI to find itself in the spotlight of almost all Eurasian countries, as well as further afield.

One of the key, and now already tangible, strategic results of BRI’s implementation is the appearance of tangible changes in Central Asia’s geoeconomic situation—a region defined by Halford Mackinder, the British geographer and one of the founders of geopolitics, as the world’s heartland and a possible key to dominating all of Eurasia.

This region, which was traversed by the Great Silk Road’s main trade arteries during the Middle Ages, has been on the periphery of world geo-economics for the last couple of centuries, a victim of shifting trade patterns due to colonialism. Now, in the context of BRI, the role of Central Asia as a transcontinental land bridge between China (the world’s largest exporter) and the EU (the world’s largest consumer market) is being redefined.

In light of the aforementioned initiative, the eagerness of Central Asian countries to take advantage of the new opportunities on offer should come as no surprise. Kazakhstan, in particular, is geographically critical to BRI’s success, due to the key land routes connecting China with the rest of Eurasia all passing through its territory.

However, the new historical opportunity for Kazakhstan and the rest of Central Asia does not imply immediate implementation. As always, the devil lies in the details, and BRI-related projects face numerous challenges and risks, both for the project’s initiator and for all other participants.

Prerequisites for BRI’s Inception?

Since the early 2000s, the Chinese authorities have used the format of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) to tackle difficult situations with the newly independent states of the Central Asian region (CAR). The most pressing was the issue of borders and the status definition for the disputed territories inherited from the Soviet Union. At the same time, when interacting with each of the CAR countries—both within the SCO framework and bilaterally—Beijing almost always had to look back at Russia.

However, as economic ties with the countries of Central Asia continued to deepen, Beijing could no longer confine itself solely to the SCO format, which, over time, had become increasingly unaccommodating of the requirements of China’s dynamically developing trade with the CAR states.