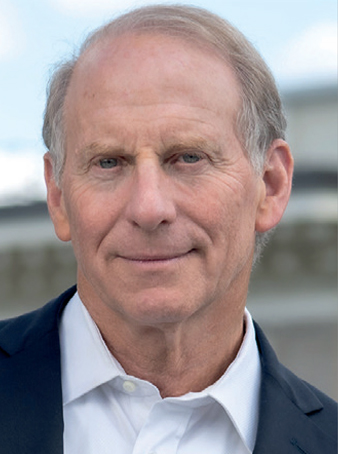

Richard Haass is President of the Council on Foreign Relations. He previously served as Director of Policy Planning for the U.S. State Department and was U.S. President George W. Bush’s Coordinator for the Future of Afghanistan. This essay is based on the “Why it Matters” podcast, episode “Perspective on Afghanistan, with Richard Haass.” © Copyright 2021, by the Council on Foreign Relations. Used with permission. You may follow Dr. Haass on Twitter @RichardHaass.

Richard Haass is President of the Council on Foreign Relations. He previously served as Director of Policy Planning for the U.S. State Department and was U.S. President George W. Bush’s Coordinator for the Future of Afghanistan. This essay is based on the “Why it Matters” podcast, episode “Perspective on Afghanistan, with Richard Haass.” © Copyright 2021, by the Council on Foreign Relations. Used with permission. You may follow Dr. Haass on Twitter @RichardHaass.

A little over five years ago, I authored A World in Disarray, whose Serbian language edition was subsequently published by the Center for International Relations and Sustainable Development (CIRSD). The book’s thesis was that the Cold War’s end did not usher in an era of greater stability, security, and peace, as many expected. Instead, what emerged was a world in which conflict was much more prevalent than cooperation.

Some criticized the book at the time as being unduly negative and pessimistic. In retrospect, it could have been criticized for its relative optimism. The world today is a messier place than it was five years ago—and most trends are heading in the wrong direction. One of these is Afghanistan, which appears to be on its way to becoming again a world leader in terrorism, opium production, and misery.

The Biden Administration’s poorly executed withdrawal from Afghanistan resulted in a lively debate on a whole host of issues related to the conduct of American foreign policy. Some have even questioned whether the United States was right to go into Afghanistan in the first place. For me, the answer was and remains unambiguous: we were 100 percent right to go in. The Taliban, which ruled Afghanistan at the time, harbored terrorists who attacked the United States and killed nearly 3,000 civilians. That attack had to go answered. Also important was the precedent the United States established, namely that it would not distinguish between terrorists and those who supported them. The United States gave the Taliban a choice—they could hand over the terrorists responsible and be spared—but they chose wrongly: a fateful decision for them.

Moreover, we made the right decision to help the Afghans forge their own government; if we did too much, our effort would have lacked legitimacy. That was the only clear thing, though. We did not think through what we would do afterwards. There was no clear plan and no consensus within the Bush Administration over the trajectory of U.S. policy. How ambitious should we be? What was our definition of success at that point? That is where things began to break down. That being said, however, I emphasize that the War on Terror, which became an important part of American foreign policy, did result in America becoming effective at diminishing the threat posed by terrorism to the United States.

The War on Terror quickly took on a global dimension—with a focus in parts of the Middle East and Africa—because that is where various terrorist cells had set up shop. We discovered that groups like al-Qaeda and others were international. They had access to money, guns, and people.

That phase of American foreign policy began over twenty years ago, and it is still ongoing—largely but not exclusively in the Middle East and Africa, but also in parts of Asia. To my mind, the struggle against terrorism is open-ended. There are some parallels with our current battle against COVID-19. You don’t eliminate terrorism any more than you eliminate a virus. These are now baked into the world of the twenty-first century.

Terrorism, in other words, is a global and open-ended challenge, although it had been centered in Afghanistan for a moment during which it had come to us most painfully and vividly. Afghanistan was where the terrorists involved in 9/11 had been trained. They were not Afghans, however: most were from Saudi Arabia and elsewhere in the Middle East. But they were supported and organized in Afghanistan, and their leader, Osama bin Laden, was in Afghanistan. Yet after the flight of the Taliban and al-Qaeda from that country—most of them quickly escaped to neighboring Pakistan—Afghanistan was no longer the epicenter of world terrorism. Terrorism had essentially dispersed.

Thus, over time, America’s reasons for being in Afghanistan changed. Competing views emerged on what should be done after the initial phase had ended. In many ways, what was done, or not done, has come back to haunt us in many ways.

Let me recapitulate. America and its allies had successfully worked with our Afghan partners, removed the old authority (the Taliban), and helped bring about a new authority led by Hamid Karzai. And then the question became: what do we do next? Not just in the context of Afghanistan but in the context of the Taliban. The feeling was that the United States could not just leave the Taliban be, because we knew that they had crossed into Pakistan. And the question was also, how do we help the new authorities in Afghanistan stand up? In other words, how do we build them up so that Afghanistan could become something approximating a normal country?

We were not talking about democracy at this point; we were talking about building up the capacity of this first post-Taliban government, so that it could police its borders and its national territory, so that terrorists would not be able once again to use Afghanistan as a piece of real estate.

I painfully and vividly remember the debates we had within the Bush Administration on these questions—on, to put it bluntly, the question of how ambitious America should be in its approach to Afghanistan. One of the common phrases used, then and now, is “nation-building” or “state-building,” but, in reality, that was capacity-building. The question was formulated in the following manner, more or less: What kind of capacities ought we try to bring about in Afghanistan?

What I proposed was that the United States and its allies would stay in Afghanistan temporarily and perform two functions. The first was that we would help the new government consolidate authority over Afghan real estate, because it is a large country—it is, for instance, more than twice the size of Poland, but its terrain is much more prohibitively mountainous. The second function was that we would help develop and train the Afghanistan armed forces. At that point, it was not clear how national its military would be, as opposed to regional, but the point was that America would help stand up an Afghan army.

Without getting into the details, suffice it to say there was remarkably little enthusiasm for doing what I had proposed. Now, admittedly, I was used to being unsuccessful in my policy proposals, but even in my career of unsuccessful attempts to influence U.S. foreign policy, this stood out. It was one of the most painful national security meetings I had ever attended. There just was not any enthusiasm.

If I had to boil down the takeaways from the discussions that took place during that period, I would say that this lack of enthusiasm reflected two things. The first was pretty legitimate and can be formulated as a question: why do we want to get ambitious in Afghanistan? The counter-argument went along these lines: this is a country with little tradition of a strong central government. Afghanistan is very tribal and regional, and it is, simply put, the wrong place for us to get ambitious. And, in retrospect, I think that was a legitimate concern. The second concern that was raised in response to my proposal—a concern that was less legitimate, in my view—was that there was much more excitement about getting involved more in other parts of the world, i.e., Iraq. And the feeling was that Iraq was a place where if America did invest sufficient resources, then the United States would have more to show for it. In other words, Iraq was a potential democracy—it was a potential model that other Arab countries might emulate. In contrast, Afghanistan was seen as an isolated one-off.

The bottom line was that Afghanistan was seen as both a poor prospect and a poor investment.

Another part of the argument I made was that we had a window: the Taliban had been routed and the new governing authority’s legitimacy was really high. We needed to build up authority. My point was that America could not remove a government and then not put something in its place.

For those who question that argument, I have a one-word response: Libya. Under the Obama Administration, the United States went in and removed Muammar Gaddafi and never put anything in his place. As a result, Libya became—and remains—a failed state. And what we learned in some cases is that bad situations can get worse. Thus, my view on Afghanistan—I did not have the Libya example at the time—was that we had to try to do something that was neither overly ambitious nor under-ambitious. My point at the time was that the United States had a moment, and that we needed to harness it. I thought that we would have had significant international help, and I felt that what I was proposing we do could be accomplished in relatively short order. But again, there was simply no enthusiasm for it.

What ended up happening subsequently was that the rate of nation- or capacity- or army-building in Afghanistan was incredibly slow. Meanwhile, this was not happening in isolation: with sanctuary across the border in Pakistan, the Taliban was rebuilding and reconstituting at a pretty good clip.

Pakistan had gone back to business-as-usual regarding the Taliban: it was operating openly out of Pakistani cities—what was then known as the North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan became one giant sanctuary for the Taliban. (For a while after 9/11, Pakistan had cleaned up its act regarding the Taliban, in part because senior members of its government happened to have been in Washington on 9/11, and, as one can imagine, very frank conversations were held with them at the time by the likes of Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage.) The historical record is clear: it is very hard to prevail in a “civil war” if one of the parties has access to a cross-border sanctuary. This is in fact what the Taliban were able to accomplish.

The point is that we had two parallel dynamics: on the one hand, a very slow one of building up government capacity, and, on the other hand, a fast and unhealthy one of the Taliban reconstituting itself, in part because the U.S. military had failed to stop them from escaping. Then we took our eye off the ball and Pakistan went ahead and allowed the Taliban to regroup and rebuild.

This was more or less the state of play at the time I left my post as U.S. Coordinator for the Future of Afghanistan and Director of Policy Planning at the State Department in June 2003. By the time the Obama Administration came to power, the Taliban had resumed all sorts of efforts within Afghanistan. The situation was beginning to deteriorate, and by then America had made the fateful decision to dramatically increase U.S. forces—a policy initiative that became known as the “surge.” There were three basic problems with this policy, which was announced in late 2009 and became operational in early 2010: one, by then America had clearly overstayed its welcome in Afghanistan; two, we had allowed the Taliban to rebuild; and three, the fact that we were surging forces increasingly involved in combat against a reconstituted Taliban meant that U.S. casualties increased and the cost of the war by every definition of the word “cost” went way up. Thus, Afghanistan went from being the “good war” to being simply the second bad war (with the first being the Iraq War).

In testimony that I gave to the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee in May 2011, I argued that, at this point, the United States should aim for an Afghanistan that was “good enough,” given local realities, limited American interests, and the broad range of both domestic and global challenges facing the United States.

My argument was based in part on an assessment that the surge amounted to an attempt to be decisive in a situation in which I did not think America could be decisive—that the surge was not going to end in a military victory in which the Taliban would sue for peace. In this period, I was instead arguing for something more modest—something “good enough” for both Afghanistan and Iraq.

Americans tend to see situations as problems, and anytime we hear the word “problem,” we immediately expect to see the word “solution.” And the problem with thinking of things as problems, as it were, is that lots of things are really situations, and, by definition, situations cannot be solved with military force or any other policies. At best, situations can be managed. This often means not what you can bring about, but what it is you can avoid. The phrase “good enough” was meant to convey that idea—that the United States needed to dial down its ambitions and simply say: what we want to avoid is a Taliban takeover of the major cities; we cannot stop the Taliban from making some inroads; but we can establish a situation that we can help sustain at an affordable cost. That is why I argued against the surge policy.

The idea animating its proponents, in contrast, was that a decisive blow was possible. And the reality was that it was not. Part of my thinking was informed by an insight made by Colin Powell—he was Secretary of State when I worked at the State Department and, prior to that had been Chairman of the Joint Chief of Staff—to the effect that military force is good at destroying things and in turn at creating a favorable context in which other things can happen. My own view derives from this insight, namely that the United States turns to its military too often.

This is not to imply that nation-building cannot work; but it works only in the right circumstances: its most famous successes were in defeated, occupied countries like Germany and Japan after World War II. Asking why it worked there, one might examine the characteristics of those societies: they were highly educated and highly homogenous; and they were both societies with strong national traditions, and so forth.

I perfectly understand that none of these things were present in Afghanistan in 2001. My capacity-building proposal, made in the wake of 9/11, was by no means guaranteed to work; but I thought it was worth a limited investment. I did not think it was a high-risk endeavor at that moment because the United States had tremendous authority and momentum and because both the Taliban and al-Qaeda were gone. As I have already said: I thought there was a window, and my view was, “let’s take advantage of this window. Worse comes to worst, it won’t work, which will still leave us in an advantageous position to deal with the consequences.”

Our unwillingness to give it a serious try set in motion a situation in which Afghanistan’s new government was never able to do what it needed. We misguidedly took on an ever-larger role in Afghanistan, which meant that we became not only behind-the-scenes nation-builders but also essentially a protagonist in the country’s civil war. And that seemed to me an escalation that was unwise.

In 2010, I wrote a book called War of Necessity, War of Choice in which I argued that all wars are fought three times. There is the political struggle over whether to go to war. There is the physical war itself. And then there is the struggle over differing interpretations of what was accomplished and the lessons of it all. In reflecting on the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, what worries me is that we could end up learning the wrong lessons.

I do not believe the lesson ought to be that nation- or state-building is always wrong—that it’s always destined to fail. I think what we really need to think hard about on the basis of Afghanistan can be formulated as a set of questions. What are the conditions that we think are positive? What are the techniques? What have we learned about sequencing? What have we learned about pacing? What have we learned about how to adjust for local culture and history?

The reason this is so important, in my view, is that we do not want to be doing everything ourselves around the world. At the same time, there are dozens of governments around the world we need to help—particularly in the Middle East, Central America, and Africa. And so, we had better learn some of the correct lessons of nation-building rather than to conclude either that it is never worth it or that it is never a good idea.

It seems to me that there are only two alternatives to learning the right lessons from Afghanistan: either we accept that we will live in a world that is much more dangerous, or we confront ourselves with having the United States get involved directly in combat operations in more places.

Such reflections touch upon one of the fundamental debates in American foreign policy. Again, we can formulate this as a set of questions: What responsibilities do we have to a society and to a culture when we come into a country and leave? To what extent should American foreign policy be about shaping and influencing the external behavior of other countries? And to what extent should what we do in the world be about influencing the domestic behavior of other states?

The way to answer any of these questions lies first in understanding that American influence is often limited and that the United States often has other priorities.

The next step involves acknowledging that perhaps the single-most ambitious task that America can imagine setting for itself is to try to change the internal workings of another society—particularly one with a long and deep culture. This does not mean U.S. foreign policy should dismiss the importance of American values, but it does mean that America must understand that there are limits of our influence—that we cannot always translate our preferences.

I’m not saying I like where this line of reasoning takes me, but that does not make it incorrect.

I still remember a dinner party that took place some time ago at which I made some version of the above argument about the Middle East. I think it would be fair to say that I was excoriated and hammered by a prominent former policymaker who was also present. His argument was, basically, that I was selling short the people in the Middle East. And I was actually accused of a kind of racism for my argument that, in effect, not everybody was ready for democracy now. My response was that I was not making a statement about individuals but rather about cultures and societies.

In some sense, of course, I do like the notion that a transformation can come about, or at least be triggered, simply by reading a translation of the Federalist Papers. But I am not willing to believe this will necessarily happen. And that is why I believe the United States has to decide what are the limits to our influence; we have to define our priorities; and we have to ask questions like, what are those things that American foreign policy is well suited to do, and what are those things that are within reach?

The withdrawal from Afghanistan and the abandonment of many Afghans most vulnerable to Taliban reprisals (e.g., women and girls, first and foremost, but really Afghans of any gender who wanted to have a twenty-first century life) worries me and causes me to wonder about American limits more broadly—not just in the context of Afghanistan.

We need to think about the fact that, for instance, we cannot convince a country like Myanmar to change its ways, notwithstanding the discrepancy between the power of the United States and the power of Myanmar. We cannot oust the military junta that took over there. The lesson here is quite basic: there is a limit to American influence in the world. The United States may very well be on the side of right and morals and virtue, but that is not necessarily the way history plays out.

There are obviously things that America can do: military intervention aside, tools of influence (both carrots and sticks) include sanctions, foreign aid, and educational opportunities. But the point is that there are still limits.

In the contemporary Afghanistan context, we know the Taliban are reimposing Sharia Law and are forcing women to wear a niqab. And we might respond to such policies by imposing one or another penalty or withhold this or that form of assistance or aid. Yet there is little to prevent them from turning to other states for the type of external support they need—states like Pakistan, Russia, or China that tend not to care about such things and have other priorities.

This means that the United States can have an Afghanistan policy in part that tries more directly to promote certain behaviors, certain norms, and certain standards; but this should not come at the price of sacrificing America’s most important priority in Afghanistan: to ensure the country does not again become a place from which terrorist can operate. This has to remain the single most important thing.

That is a more classic foreign policy interest. And as we showed after 9/11, the United States has the mechanisms to act if the Taliban chooses again to harbor terrorists. The Taliban may or may not have internalized that lesson. But no one is going to launch an intervention in Afghanistan over the reimposition of Sharia Law or the fact that women are again being treated abominably—as tragic as that is.

This is where we are now—the point to which we have come, at least in the context of Afghanistan. It is not what I would have preferred. That is one of the reasons why I had favored the United States maintaining a small presence in Afghanistan—not because it would have meant peace or because it would have led to a military victory, but because I thought that it would avoid some of the scenes that we have been seeing since the summer of 2021. And that, to me, was a consideration in my argument for maintaining a small presence—the fate that would likely befall girls and women, as well as men in Afghanistan.

Obviously, this was a point on which I differed with the Biden Administration’s policy on Afghanistan. Its argument was, basically, that the United States is no longer prepared to have American forces stay in Afghanistan any longer—and potentially putting themselves in harm’s way—in order to deal with non-terrorism issues, as gut-wrenching as they are. That it was one thing to deal with Afghanistan as a terrorist haven and something else to deal with it as a human rights nightmare. With regards to the latter, President Biden basically said, ‘we will turn to diplomacy.’ Well, quite honestly, diplomacy is not going to accomplish much.

To be fair, President Biden inherited a kind of ‘you can’t have your cake and eat it, too’ situation. We had a small military presence. Americans hadn’t been doing combat operations for several years prior to his election. We had not had a combat fatality for one and half years, at that point. And we had managed to get to a point where the benefits and the costs were not out of alignment, and one of the benefits was that the quality of life for Afghan girls and women was improving.

President Biden was not willing to take the risk that the costs of a continued small American military presence would go up. He obviously did not want to face the decision of having to increase U.S. forces if the security situation deteriorated, so he essentially initiated a policy that, in my view, brought about a set of truly terrible outcomes. And my guess is he would say, ‘I don’t like these outcomes any more than you do, but I just wasn’t willing to take the risk of what the price would be of our staying.’

It would be wrong to say these are not a legitimate set of concerns or that there was no legitimate debate that could have been had about the merits of the agreement signed by the Trump Administration in February 2020—but not over the way the withdrawal was designed and implemented, which was terrible. The agreement negotiated by the Trump Administration to get America out and undercut the Afghan government asked virtually nothing of the Taliban. I was the U.S. envoy to the Northern Ireland peace talks: we asked much more of the provisional IRA in Northern Ireland than we ever asked of the Taliban: we demanded a cease fire and we demanded that they give up their arms. We did neither with the Taliban.

What the Trump Administration negotiated and signed was not a peace agreement; it was an American withdrawal agreement. I thought the Trump Administration was dead wrong to do it. I thought President Biden, who has had no trouble distancing himself from other things he inherited from President Trump on issues like Iran, climate change, the World Health Organization, and so on, should have distanced himself from this. Instead, he essentially, followed through on what President Trump had wrought.

One argument that those who defended the withdrawal made was that public opinion surveys indicated many Americans were in favor of getting out of Afghanistan. But this was not an intense sentiment—a driving concern—that, for instance, affected the way people voted in the presidential election. In fact, I think that if pollsters asked Americans whether they wanted their country to get out of most places, the answer would be similar. But again, the issue of intensity comes up: for example, the protests that took place in America in 2020 and 2021 had to do with race and policing issues. They were not about Afghanistan. No one in America was protesting the war in Afghanistan like Americans had protested the Vietnam War.

The question of public approval of the Biden Administration’s withdrawal plans also touches upon another aspect of U.S. policymaking: traditionally, neither foreign nor domestic policy is conducted on the basis of short-term popularity. After all, we do not have referenda every day in America, or anywhere else, for that matter. In the United States, we have a representative government, and our leaders are given the responsibility to make tough decisions. The fact that Americans may today say they like that we’re out of Afghanistan does not mean they will like it in a couple of years if we face problems of terrorism at home, or if human rights atrocities happen in Afghanistan.

That being said, I wish Americans were more consistently interested in the world, particularly since the world is interested in us—for good and bad. The latter seems to me simply to be a fact of life. And the reason foreign policy is so important for America is that what we do and do not do has an impact on the world. There’s a loop there: the world influences us, and we can influence the world.

And I think what’s interesting about Afghanistan, if we look at the last 20 years, is that there have been some moments when we got it right—e.g., initially after 9/11. But I also think that along the way we have both done too little and too much—we have overreached and we have under-reached.

And since around the start of 2020, the United States has done a lot of under-reaching. And I think early on—so, say, between 2001 and 2003—we also under-reached in aspects of the nation-building project (I know this is a controversial view, but I think it’s quite a defensible one). And clearly, with the surge and other things, we overreached: we put too many forces into the country at an inopportune moment.

My bottom line is that it is important to come away from Afghanistan with the right lessons for American foreign policy. The only thing worse than making mistakes is not learning from them.