Krishna B. Kumar is Director of International Research and Distinguished Chair in International Economic Policy at the nonprofit, nonpartisan RAND Corporation and Director of the Pardee Initiative for Global Human Progress at the Pardee RAND Graduate School. He also serves on the board of the multi-stakeholder coalition Solutions for Youth Employment (S4YE). You may follow him on Twitter @kbkumar_.

Krishna B. Kumar is Director of International Research and Distinguished Chair in International Economic Policy at the nonprofit, nonpartisan RAND Corporation and Director of the Pardee Initiative for Global Human Progress at the Pardee RAND Graduate School. He also serves on the board of the multi-stakeholder coalition Solutions for Youth Employment (S4YE). You may follow him on Twitter @kbkumar_.

The impact of the COVID-19 crisis has been felt strongly in the Middle East, as in the rest of the world. Much of the near-term actions in the region will be aimed at mitigating this crisis by enforcing social distancing, testing and treating the affected, providing economic assistance, and ensuring a speedy economic recovery. Even when the current virus is conquered and the state of public health and the economy return to pre-crisis conditions, many countries will still stay exposed to another endemic disease: youth unemployment.

Unemployment amongst youth, typically defined as being between the ages of 15 and 24, has never dipped below 25 percent in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region during the last 25 years—compared with the world average of 13 percent—and exceeded 40 percent in Palestine and Saudi Arabia in 2018.

The MENA region is heterogeneous in economic development, and while it is sometimes useful to view them in different categories—like the natural-resource rich countries (most of the members of the Gulf Cooperation Council), labor-rich and less wealthy countries (like Egypt and Algeria), and conflict-affected countries (like Iraq and Syria)—youth unemployment is a challenge all across the region. The unemployment rates in Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Yemen all exceed 25 percent. Therefore, we treat the region as a collective whole rather than split into categories.

To understand the economic, social, and political ramifications of such a high level of unemployment, especially in the context of the current pandemic, it would help to step back and start with a brief examination of uprisings that erupted in MENA in Spring 2011—now collectively known as the Arab Spring.

The Arab Spring

The Middle East was not spared the effects of the 2008 Great Recession, and together with Europe experienced one of the largest declines in GDP (over 11 percent)—mainly due to the drop in international demand for oil. Even when GDP bounced back, the lack of percolation of the benefits down to all segments of society caused the upheavals of 2011.

The Arab Spring was a series of pro-democracy uprisings that flared up in several countries in the region, which can be traced back to the self-immolation by a street vendor in Tunisia as an ultimate act of protest against the seizing of his vegetable stand over his failure to obtain a permit. The ensuing demonstrations inspired similar ones in Egypt, Libya, Yemen, Syria, Bahrain, and elsewhere. Regimes were toppled and leaders were killed, and in the case of Syria, a civil war followed—a conflagration that created one of the worst humanitarian and refugee crises of our times. The impact of this upheaval was felt beyond the Arab world in countries such as Greece and Spain, and cities such as Santiago, Chile, and Stockholm, Sweden. While political factors were clearly behind this public revolt, they are hard to separate from the economic factors. This was to be expected, as good governance and enforcement of the rule of law are inextricably intertwined with economic performance.

In many of the countries affected by the Arab Spring, a flourishing private sector was lacking, the investment climate poor, and prospects for economic growth grim. The Arab world was experiencing a “youth bulge” at this time, with half of its population under the age of 20. Since youth are starting their careers, the level of unemployment among them is a good barometer of economic malaise. In 2010, the unemployment rates averaging 24 percent in the Arab World—with women experiencing unemployment at a rate exceeding 38 percent—were viewed by many as a major reason for rebellion. Well-educated youth were not immune, and might have been even more dissatisfied by the lack of quality jobs. It is also best not to confuse years of schooling with education in the region, given its uneven quality.

The net result was that youth—many of them students—played a central role in the uprisings, using them to air their grievances about the lack of governance that left them with few jobs or economic prospects. Gallup World Poll data indicated low levels of life satisfaction in many countries in the region, with those belonging to the middle class feeling stuck. And the social contract that relied on public sector jobs and food and fuel subsidies came under strain, with an anemic private sector unable to pick up the slack in job creation.

The reverberations of the Arab Spring continued to be felt until the onset of the COVID-19 crisis.

As COVID-19 Struck

While the peak of the “youth bulge” might have passed, the Middle East is still a young region. The median age in Iraq and the West Bank is under 22; in Egypt it is 24. And in 2019, according to the World Development Indicators, the youth unemployment rate stood at 27.5 percent, and for women, close to 40 percent. In other words, the youth unemployment situation, which was a crucial contributing factor to the onset of the Arab Spring, has not improved since then.

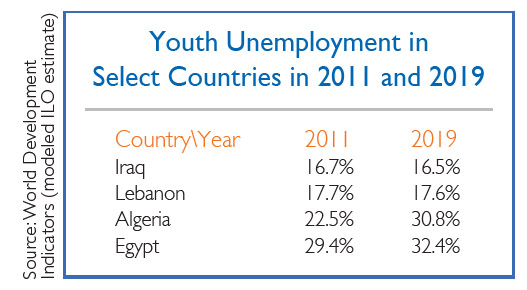

The table below compares the youth unemployment rate in 2011 and 2019 for four countries, which, as will be outlined below, experienced major unrest in 2019. There has been little progress in the unemployment situation in these countries during this period, and in the case of Algeria and Egypt, it has actually worsened.

While the youth unemployment rate is an important labor market indicator, some have additionally started using the concept of NEET (Not in Employment, Education, or Training): the percentage of youth who do not currently have a job and are not enrolled in human capital investment activities such as education or training. NEET focuses on youth who are at risk as they lack access to both jobs and learning opportunities. The NEET rates have also been high in the MENA countries. For instance, in 2012, around 25 percent of youth were classified as NEET in Jordan and Tunisia, and over 30 percent in Egypt and Palestine.

Moreover, on several other developmental fronts, such as poverty levels and gender parity, conditions have deteriorated. Democratic change, like economic change, has been as elusive as ever. A lack of improvement in governance, decreased political participation and civil liberties, increased poverty among non-oil exporting countries, and rising inequality have characterized the intervening period. While Tunisia, where the 2011 outbreak started, provides a ray of economic hope, having avoided anarchy, doubts remain there too on both the economic and political fronts, with Tunisians’ perceptions of wellbeing not keeping pace with increasing per capita GDP. The steady decline of oil prices over the decade from around $100 a barrel to $30 added to the economic woes of many countries.

The Syrian civil war that ensued after the Arab Spring, and the rise of ISIS and the battles to contain them, saw over six million refugees flee to neighboring countries in the Middle East; this put severe additional strain on already fragile economies, labor markets, and public services.

Consider in this context the findings of a 2018 study by the nonprofit RAND Corporation entitled “Opportunities for All” that examined labor markets in Turkey, Jordan, and Lebanon with the aim of seeking mutually beneficial opportunities for host countries and refugees. Based on a survey of refugees in these countries (half of whom were under the age of 30), the study found that refugees were getting by (finding informal jobs at low wages) but were hampered by regulations and restrictions—including limitations on the types of occupations and sectors in which they could work—and a geographical mismatch of where they live and where the jobs are. Despite the hospitality of the host countries, social tension was high between the refugees and host workers, given the scarcity of jobs. For their part, the host countries felt that assistance and investment by the global community were not commensurate with the magnitude of the public good they were providing for the world as a whole by hosting the refugees.

Amidst this economic weakness and political disarray, a new wave of upheavals spread through the MENA region in late 2019, with youth again playing a major role. Protests in Iraq started in October of that year. Though the dismissal of a popular counter-terrorism chief was the trigger, three other factors fueled the uprising: unemployment, poor governance, and the harsh initial response by the government that resulted in numerous deaths.

October 2019 also saw the start of demonstrations in Lebanon, which resulted in Prime Minister Saad Hariri resigning before the end of the month. The fire was ignited by a tax on internet-based calling services, but predictably corruption and economic stagnation that had resulted in a lack of job opportunities fanned the flames. Low growth, diminished capital inflows, high youth employment, an overvalued fixed exchange rate for the Lebanese Pound, and government profligacy that has resulted in an enormous debt-to-GDP ratio of over 150 percent—the third highest figure in the world—have left the Lebanese with little hope.

The trouble in Algeria started earlier, when protestors took to the streets in February 2019 demanding structural changes in their government, which brought down the long running presidency of Abdelaziz Bouteflika. Youth, facing poor job prospects, played a big role. And the unrest continued well into the year.

Even Egypt, where dissent is not tolerated by the government, saw an outbreak in September 2019. Despite signs of growth, the lack of percolation of economic gains to the bottom socioeconomic rungs in a country that suffers from endemic poverty, in addition to political dissatisfaction, appears to have been the reason.

Finally, the unrest in Sudan that started at the end of 2018 over a hike in food prices and economic mismanagement spilled over into 2019, when President Omar al-Bashir was overthrown in a coup. This led to a new wave of protests for democracy, causing a crackdown by security forces.

Except for Egypt, the aforementioned countries were not the primary scenes of demonstrations during the Arab Spring. And while their respective citizenries were still hankering for political reforms, protestors were more peaceful this time around and rejected sectarian divisions and political parties of all stripes. Given these differences, one might not want to rush to label the 2019 outbreaks as Arab Spring 2.0—updated for the times of social media and using the lessons learned from the original version—but the signs are ominous for the region and the causes for these agitations eerily similar to those of the 2011 uprising.

The Great Recession, the Arab Spring, the drop in oil prices, the continuing effects of the Syrian civil war, and a new wave of protests and turmoil had already wreaked havoc in the region before the COVID-19 pandemic struck a further blow. Before examining how the crisis caused by the pandemic could further complicate the situation, it would be useful to survey the reasons for the stubborn persistence of youth unemployment in the region.

The ‘Why’ Question

As mentioned earlier, youth are at the beginning of their long careers and typically go through initial jobs acquiring skills and experience that will benefit them throughout their careers. This is one of the reasons a young person just entering the labor market has to start right, getting a job soon after finishing formal education and one that offers prospects for upward mobility.

The linear model of a worker starting with and sticking with an occupation and an industry, perhaps even a specific firm, has been upended by rapid technological change. These days, a typical worker will have to switch jobs, firms, occupations, and industries during the course of his or her life. Navigating these switches require acquiring through education not only a combination of technical and soft skills but also the ability of “learning to learn.” Workers also need to obtain relevant experience from the jobs they hold early in their lifecycle. When these job opportunities do not exist for youth, they both lack current employment and face diminished future economic prospects.

For instance, research using Canadian data suggests that graduating from college during a recession—when jobs can be scarce and do not pay well—can result in losses of annual earnings of 9 percent during the initial years, with the effects still lingering for a full decade. It is therefore not difficult to see why youth, no matter their level of education, feel dejected where job opportunities do not exist, and in the absence of other outlets, take to the streets.

There’s a common formula for conceiving the youth labor market in terms of labor supply (youth with different skill levels able and willing to work), labor demand (employers able and willing to hire such youth), and the system that exists to match the workers to employers. Viewed through this lens, the reasons for the stubborn persistence of youth unemployment in the MENA region become apparent.

On the supply side, with the exception of Yemen, primary education attainment among youth is 80 percent or higher. But this ratio drops when it comes to secondary education, which is typically the minimum level required for middle-skilled jobs (in labor-rich Algeria, for example, only around 50 percent of the young have secondary attainment). Furthermore, the quality of education is low in many countries, as measured by poor outcomes on international benchmarks such as Progress in International Reading Literacy Study and Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study. All countries in the region are at the lower half of the scale, with many at or near its very bottom.

Technical Vocational Education and Training (TVET), does not fare much better. There is a stigma attached to TVET, resulting in very low enrollment, and the training provided is of low quality that does not further employment prospects. There is a sizeable mismatch in skills in the region as the youth do not acquire the skills needed for the labor market. In his 2019 assessment of the youth employment challenge in the MENA region, Nader Kabbani of the Brookings Institution additionally notes the demographic wave that has increased the sheer number of people looking for jobs as well as additional factors that have led to the economic exclusion of women among the supply factors that have hampered employment.

On the demand side, employment in the public sector has been part of the social compact in the MENA region for decades. The share of public sector employment in the region has exceeded the corresponding share in other parts of the world; in the 2000s, the share of public sector jobs in Jordan was as high as 40 percent. But this share has been declining over time, driven primarily by a slowdown in new hiring.

In 2018, the World Bank published a comprehensive analysis of the causes of the Arab Spring, entitled “Eruptions of Public Anger.” The report discusses, inter alia, why the private sector has not stepped to fill in the gap. It finds that elite capture and crony capitalism in the private sector have resulted in a mix of large, well-connected monopolistic firms and small firms employing very few, with the net result that a sizeable number of jobs have simply not been created.

While online job-matching services are increasing in the MENA region to connect employees with employers, challenges remain in reaching lower-skilled workers and those in the informal sector. A typical MENA country produces one third of its GDP and employs 65 percent of its labor informally (often characterized by the lack of social security coverage such as pensions and health insurance). The rates are even higher for youth, which highlights the magnitude of the job-matching challenge.

Kabbani’s Brookings report adds excessive regulation and inflexible labor laws to this list of demand failures, together with the lack of labor-market information systems and career planning resources for jobseekers, which would hamper job matching. He also notes that continuation of such policies, weak implementation and coordination, and a lack of reliance on evidence have caused many policy responses and initiatives to fail, resulting in the current status quo.

The importance of good governance and sound policies in creating good education and training systems, alongside that of providing an environment conducive to business formation and job creation, cannot be overstated. Political and economic change go together, and it is therefore not surprising that Arab Barometer surveys found the three main reasons respondents cited for the Arab Spring were economic betterment, fighting corruption, and demanding social and economic justice.

Ramifications

As we have seen, the COVID-19 pandemic is just the latest in a series of back-to-back shocks that have hit the Middle East. The repercussions of this series of tumultuous events will be felt deeply across all aspects of life in the Middle East: economic, social, political, and geopolitical.

While the exact causal mechanisms between social conflicts and economic development continues to be debated, there seems little doubt that they are interlinked. The worst-affected parts of the Middle East can be viewed as languishing in an equilibrium where both co-exist. There is suggestive evidence that the Arab Spring might have already had a negative impact on economic growth in MENA countries, especially the non-oil producing ones. And as a result of the COVID-19 crisis, Brookings experts predict that livelihoods will become more strained, social capital that has already become frayed by incessant conflicts will further erode, and fiscal balances of countries will be negatively impacted as they are forced to respond with stimulus packages.

In addition, the IMF has forecast that the MENA region’s economy will contract by 3.3 percent in 2020—more than the 3 percent contraction they predict for the whole world. A further slide in oil prices could worsen the contraction. Lebanon is expected to contract by as much as 12 percent. The deteriorating economic and fiscal situation will have serious political implications as countries were already performing a precarious balancing act of their food and energy subsidies during the agitations of 2019.

Oil-producing countries will not be spared as global demand (and prices) for oil drops. The dislocation of migrant foreign workers they employ in large numbers is also a matter of great concern—especially since a sizeable proportion of these migrants come from other parts of MENA. The social spending some of these countries undertook out of their oil revenues in response to the Arab Spring so as to assuage their populations have already put them in dangerous fiscal positions, as oil prices are nowhere near their fiscal breakeven prices.

On the strategic front, experts at the RAND Corporation warn that the effect of the COVID-19 shock could be to heighten the U.S.-Iran conflict, see greater engagement of China and Russia in the region, and result in a further weakening of democracies. They also foresee the possible further destabilization of Iraq and Lebanon, exacerbated risk from internally displaced people and refugees, and a collapse of small and medium-sized enterprises.

We know that even in what passes for “normal times” in the region, the prospects for youth employment is a proverbial canary in the coalmine, as it lays bare underlying structural social, economic, and political weaknesses.

The COVID-19 crisis, coming at the heels of all crises past, with dire predictions of the collapse of businesses and economies as a result, will only make the youth unemployment situation in the region worse. Even businesses that survive the latest crisis will become more reluctant to hire youth, and instead fall back on the safety of more experienced workers, whose availability will increase as unemployment rates soar.

Looking past the havoc wreaked on human capital accumulation by closures of educational and training institutions to reduce the spread of COVID-19, much needed further investment in these institutions is likely to get short shrift as government budgets creak under the weight of all other demands to both combat the crisis and stimulate a recovery. Predictions of increased authoritarianism do not augur well for the easing of regulation and decentralization required to grow the private sector.

Facing even bleaker economic and political prospects, youth may be ever more likely to take to the streets perpetuating the cycle of conflicts and economic collapse.

Options

Addressing effectively the myriad challenges posed by youth employment is always complex. In the Middle East, an already bad situation has been made more dire by multiple crises. While there are aspects of the phenomenon we still do not fully understand—and evidence of effectiveness is mixed on some of the approaches that have been tried to increase youth employment prospects—there is a lot we do understand on strategies and policies that seem promising and worthwhile to pursue. This alone should give policymakers much needed hope.

Many initiatives have attempted to address the youth employment problem in MENA and elsewhere head on. For instance, Solutions for Youth Employment (S4YE) is a coalition of public and private sector and civil society organizations, government officials, think tanks, and youth organizations that provides thought leadership and resources for catalytic action to increase youth employment. The coalition’s “2015 Baseline Report” documents empirical evidence suggesting youth employment interventions, especially those that provide skills or entrepreneurship training, as well as interventions to promote entrepreneurship through access to finance combined with skills training, show promising results. It also notes that youth employment is an important enough consideration to figure in two of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (namely, SDG4 and SDG8).

Another of this coalition’s reports, written by RAND Corporation researchers, does a deeper dive into what we know about youth skills and employment programs for low- and middle-income countries.

That paper finds active labor market programs designed to overcome demand and supply market failures such as financial constraints and imperfect information suffer mainly from the failure of governments in not implementing them well, especially due to lack of accountability. The report also notes that while there are benefits to private sector involvement in training, such as designing market-relevant training curricula, it has been difficult to incentivize adequate participation. Lack of trust in the government by firms can prevent the formation of effective public-private partnerships. In addition to forging such trust, the government has a role in working with private employers to develop a national workforce system, instituting matching payments or vouchers for on-the-job training, setting up advisory councils to provide assistance to businesses in youth training and employment, encouraging the use of private providers for training and employee placement, and drawing upon a growing evidence of best practices from around the world in designing youth employment programs and initiatives.

At this juncture, when countries in the region are spending large sums as stimulus to economies battered by the COVID-19 crisis, the question arises whether they will be able to afford to spend on youth employment programs.

Some of the stimulus is aimed at businesses and will therefore help stabilize the employment situation. More importantly, addressing the challenges mentioned above—such as excessive regulation, inflexible labor laws, and lack of trust citizens and the private sector have in the government—will require resourcefulness and the political will to pursue even more than they require resources. There is a reason that much of the above discussion on what might seem a purely economic issue has centered on governance. Additionally, dropping oil prices can give a new impetus to oil-rich countries to diversify into other sectors and further create new job prospects for youth.

Is the aftermath of a global pandemic the right time to be tackling a longstanding issue such as youth unemployment? Actually, one can argue it is exactly the right time to do so. Why are actions to preserve and grow economies in the wake of the pandemic, and provide better services and accountability needed if not to improve the wellbeing and secure the future of the region’s youth? Especially in a region where over half the population is under the age 30?

An unprecedented crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic could actually become a catalytic moment for Middle East governments to reaffirm the empowerment of youth by improving their wellbeing and employment prospects. As we have seen, the costs of not doing so are huge. The ramifications go well beyond economics into society, politics, and security. Governments at this juncture can well do without the chaos and conflicts that could arise from youth feeling a sense of hopelessness. On the other hand, a credible commitment to the issue of youth employment can rally the population around a common and popular cause, and infuse much needed hope amidst all the grimness and bleak prognoses. It has the additional advantage of positively channeling the energy, innovation, and entrepreneurship youth naturally bring toward the task of reconstructing and reviving the region’s economies.

An unwavering commitment to fostering youth employment—and thus to overcome the crisis beyond the crises—seems necessary not only to ensure a prosperous future for the very youthful MENA region, but also critical to guarantee stability and security in the time to come.