Mustafa Çıraklı is an Associate Professor of International Relations and Director of the Near East Institute at Near East University.

Mustafa Çıraklı is an Associate Professor of International Relations and Director of the Near East Institute at Near East University.

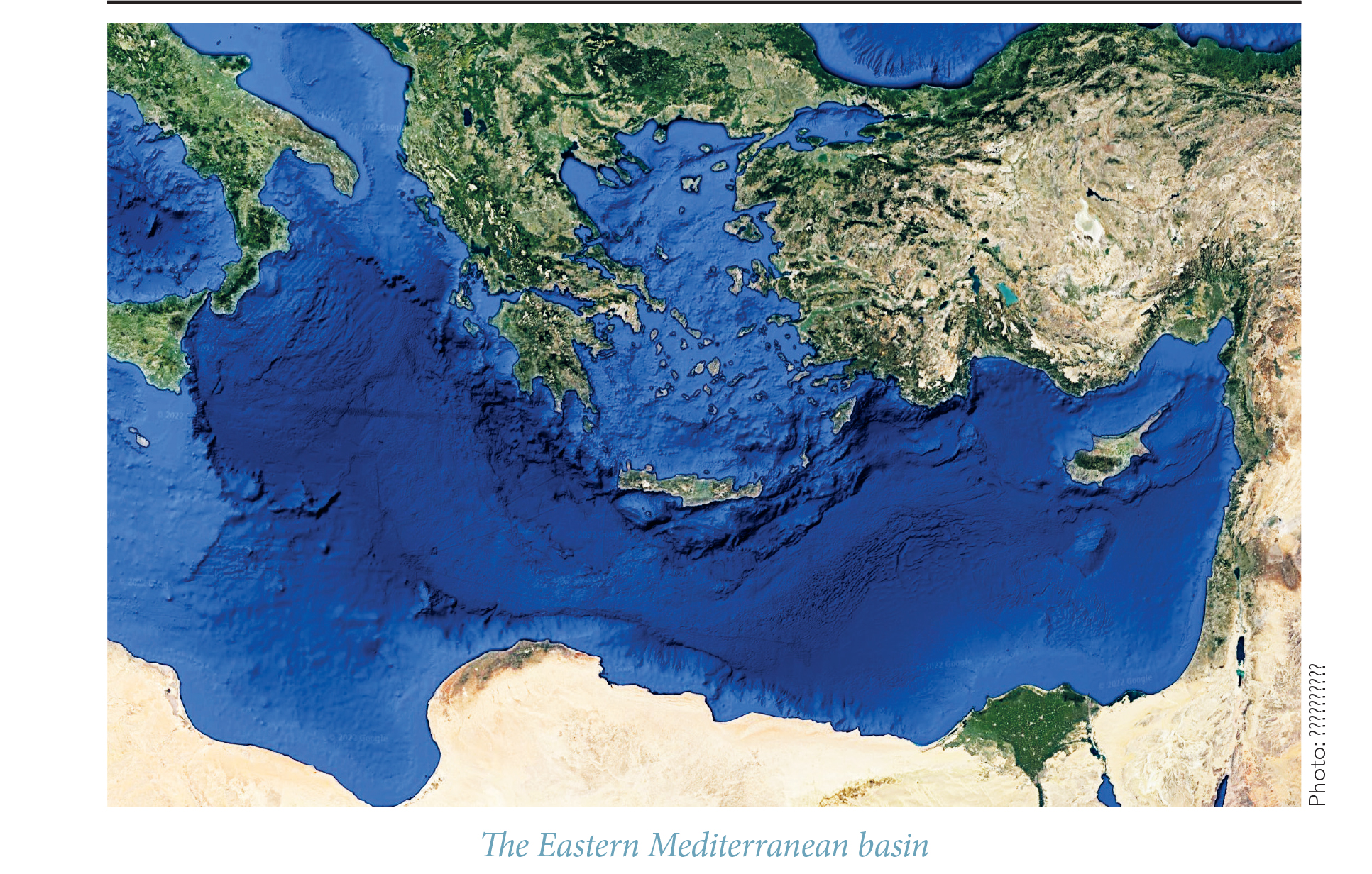

The exploration and discovery of offshore natural gas resources in the waters of the Eastern Mediterranean over the past two decades has been quickly followed by a resurgence in territorial disputes. This has turned the basin into a ticking geopolitical time-bomb that carries the potential for spiraling into a regional conflict with important spillover effects for Transatlantic relations.

More specifically, the lack of an agreement concerning the exploitation and equitable sharing of these resources, inextricably linked to the unresolved “Cyprus problem” and the competing claims over maritime jurisdiction areas between Turkey, Greece, and the Republic of Cyprus (RoC) has increased the chances not only for a dangerous Greek-Turkish clash. It has also increased the likelihood of a weakening of the Western alliance through an emboldened France ready to draw a separate course from NATO, both by taking sides in such a conflict and in relation to wider European security.

Turkey, for its part, has on numerous occasions called for an “Eastern Mediterranean Conference” to resolve pending issues and outstanding conflicts through peaceful means. In the same vein, the country’s foreign minister, Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu, reiterated that there are indeed only two choices: lock horns or find a “win-win formula” to define a mutually-beneficial way forward.

While an international conference may not deliver a panacea—given the multiple points of contention—diplomatic engagement would still help stabilize the Eastern Mediterranean through the resumption of dialogue. Seeking to contain the crisis, Turkey has already shown restraint in its response to what it views as the violation of its sovereign rights. With the encouragement of the United States and its European partners, Turkey also resumed exploratory talks with Greece and continues to explore backdoor channels to normalize strained relations with regional neighbors (with some success), including Israel and Egypt—the two countries that have expressed reservations toward the Turkish calls for the multilateral conference on the Eastern Mediterranean when the president of the European Council, Charles Michel, floated the idea in late 2020.

But Turkey needs more support and assurance to sustain its tentative de-escalatory approach. A renewed effort now by Washington and Brussels toward convening the aforementioned conference would go some way toward it.

A Dangerous Standoff

Turkey’s activities in the Eastern Mediterranean are based on a maritime agreement signed with the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) in 2011 and with Libya’s former Government of National Accord, which allowed Turkey to re-draw the EEZ and continental shelf zone boundaries within the Eastern Mediterranean.

The Turkey-Libya deal is widely dismissed by Greece and the RoC—but also by France and Egypt—as null and void. Licenses granted by the TRNC are also disputed, with the position of both Greece and the RoC being that the TRNC, which they and many other states consider to be a breakaway entity, has no authority to issue licenses.

Moreover, from a Greek and Greek Cypriot perspective, Ankara is to blame for the current escalation of tensions resulting from Turkey’s decision to pursue its own exploratory activities in the region. Asserting Greek claims to sovereignty over most of the Aegean, Greece and the RoC also accuse Ankara of illegally operating within each of their respective Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ). The RoC’s position is that it has a sovereign right to explore and develop all the island’s natural resources since it is the sole legal and legitimate government of all of Cyprus. In that vein, the Greek Cypriot government has been raising its objections with both the United Nations and the European Union (EU) over Turkey’s gas exploration and drilling activities in Cypriot waters, claiming that Turkish actions violate its sovereign rights. The RoC has also pointed out that “all Cypriots” would benefit from revenue that may come from drilling under its aegis. To that end, Nicosia has offered Turkish Cypriots a share of possible gas revenues, should Ankara recognize the RoC’s sovereign rights over the island’s energy resources.

For Turkey though, the territorial claims of both Greece and the RoC are groundless, with Turkish officials accusing both Athens and Nicosia of trying to exclude Turkey and its Turkish Cypriot kin from reaping the benefits of the region’s oil and gas findings. Also, the TRNC argues—as does Turkey—that the Turkish Cypriots have equal rights and should have a say in managing the island’s resources, independently of the outstanding Cyprus problem. To be more exact, Turkey objects to the EEZ claims of the Greek and the Greek Cypriot sides on the grounds that, one, these claims deny the co-ownership rights of the Turkish Cypriot community; two, they do not respect the rights and interests of all stakeholders; and three, they distort the equitable delimitation of maritime boundaries under the principles of international law.

On the Aegean meanwhile, the ensuing war of words between Turkey and Greece over maritime rights nearly came to boiling point during the first summer of the COVID-19 pandemic. On 21 July 2020, Turkey announced that it was sending its Oruç Reis research ship to carry out a seismic survey in the South-eastern Aegean Sea claimed by both Turkey and Greece as part of their respective sovereign continental shelfs. A series of escalating moves and countermoves led to the longest and most fractious standoff between the two NATO allies in over 20 years.

A breakthrough appeared on 8 October 2020 when the two sides agreed under Germany’s mediation and with the full U.S. blessing, to resume exploratory talks for resolving their maritime disputes. But a few days later, on 11 October 2020, Turkey withdrew from the talks and released a NAVTEX—or a navigational warning—that it would be conducting surveys on the waters 6.5 nautical miles off the Greek island of Kastellorizo, which is located a few kilometers off the southwestern-most point of Turkey’s Turquoise Coast. After a brief battle of heated exchanges, another space opened for resuming exploratory talks when Ankara pulled back the Oruç Reis from the disputes zone in late November 2020 and announced a month later that the vessel would carry out seismic research in uncontested waters until 15 June 2021. In January 2021, following a meeting of delegations in Istanbul, the two sides announced that the high-level contacts would continue in Athens.

Tensions were ramped up again in March 2021, however, when an unexpectedly volatile press conference between the two countries’ foreign ministers, Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu and Nikos Dendias, saw the two men trading accusations on maritime borders, migrants, and the treatment of minorities. Calm was ensued after a more amicable meeting in May 2021 during Çavuşoğlu’s visit to Athens, which saw the two sides announcing that they had agreed to work together for better ties.

More recently however, on 18 September 2021, fresh tensions were sparked after Turkish frigates stopped the Italian-operated vessel Nautical Geo from conducting surveys on Greece’s behalf, 6 miles off the Greek island of Crete. Turkey subsequently asserted that it would resume its own surveys if the RoC proceeds with its planned drilling by the end of 2021. In early December 2021, Turkey threatened to block any unauthorized search for gas and oil in its economic exclusive zone in the eastern Mediterranean after the RoC awarded hydrocarbon exploration and drilling rights to a venture of Exxon Mobil and Qatar Petroleum in an area that lies in part in what Turkey claims is a part of its continental shelf.

Ankara’s Conundrum

Bickering over Eastern Mediterranean maritime boundaries were initially a local affair, revolving around competing sovereignty claims among the RoC, Greece, and Turkey. During the past six years however, the region’s offshore natural gas resources have witnessed high-stakes geopolitical jockeying not only among the three Mediterranean countries themselves, but also other littoral states and outside international actors.

A key turning point in this regard was the August 2015 discovery of Egypt’s Zohr natural gas field by the Italian energy giant Eni. Eni’s Zohr discovery, considered to be the largest Eastern Mediterranean gas find to date, increased the prospects that some of it could be exported. Eni, which is also the lead license-holder in the RoC’s gas fields, then began to drum up support for a plan to pool Egyptian, Cypriot, and Israeli gas and to fast track production by utilizing the existing natural gas infrastructure in Egypt —where it also holds a large equity share—to export it to the European Union as liquified natural gas (LNG).

Irked by the idea that it was no longer considered the only export hub for the Eastern Mediterranean gas, Turkey retaliated through a limited naval action. On 23 February 2018, the Turkish navy blockaded an Eni drillship before it could reach its destination on the east coast of Cyprus, forcing the vessel to withdraw. Eni responded by striking a partnership with the French energy giant Total in all its seven Cypriot licensing blocks, a move that catapulted France into the middle of the Eastern Mediterranean energy landscape.

Then, in March 2019 leaders from Greece, Cyprus, and Israel—with U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo at their side—signed an agreement on the proposed “EastMed pipeline.” The project took on institutional form in September 2020 when the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF) was established as an international organization by Greece, Cyprus, Egypt, Israel, Italy, Jordan, and the Palestinian Authority. The final step to setting up the EMGF and its Cairo HQ was cleared after Egypt ratified its founding charter in October 2019. Turkey has insisted that it was left out purposefully and has blamed the EMGF for taking Greece and Cyprus’s side.

Also alarming for Ankara, in December 2019, U.S. President Donald Trump signed the Eastern Mediterranean Security and Energy Partnership Act, which put Greece and the RoC at the forefront of US policy in the region—a role historically played by Turkey.

This was the context in which Turkey shifted in its foreign policy preference towards a more assertive diplomatic posture in the Mediterranean basin. Turkey expressed its displeasure at these developments by engaging in a series of limited countermeasures (e.g., sending exploration and drill ships into Cypriot waters, with naval escort). In late 2019, Ankara also signed a security and maritime border agreement with the Tripoli-based Government of National Accord, which was followed by the deployment of Turkish troops against the Haftar forces backed by the UAE, France, and Russia. Most remarkably, the new maritime border agreement introduced a vertical line across the Mediterranean: it re-drew the EEZ and continental shelf zone boundaries and marked the Turkish-Libyan economic zone. The aim was to delay the pipeline plans put forward by Greece, Cyprus, Egypt, and Israel.

Another Turkish grievance relates to the situation in Cyprus. There is a growing conviction in Turkey that the RoC’s refusal to discuss Cypriot gas resources with the Turkish Cypriot side reflects a wider Greek Cypriot unwillingness to accept the Turkish Cypriots as co-equal partners in government. The general mood in Turkey also seems to be that Turkey and the Turkish Cypriots did what they could and that the proposals they tabled, together with the TRNC, for the joint development of the island’s natural gas resources gave the Greek Cypriots ample room for compromise. Successive rounds of talks—held in 2017 and 2018 between the two sides, along with the guarantor nations of Greece, Turkey, and the United Kingdom—ended in deadlock. Turkish and Turkish Cypriot warnings regarding what they saw as unfair actions by the RoC fell onto deaf ears. At that point, Ankara began trying to counter these developments by acquiring research and drilling ships and sending them, often with naval escorts, into contested waters.

From a security perspective too, Turkish actions are not surprising. Turkey aspires to have regional clout, and hosting the Eastern Mediterranean pipeline would cement that. But its positioning within the Eastern Mediterranean energy landscape is also strategically important for the country’s geopolitical reach, and for its ability to act. In this sense, Turkey confronts the possibility that joint action by the Greek and Egyptian navies could, in theory, close off the Mediterranean to Turkey by forming a blockade from the outer islands of the Dodecanese (Rhodes, Karpathos, Kasos) to Crete and then to the North African coast at the Eastern Libya/Western Egypt border region.

The French Connection

In the same vein, Ankara sees the initiation of a new, anti-Turkish axis (with France at its helm) in two other developments, aside from the deepening security cooperation between the Mediterranean countries: the trilateral RoC-Greece-Egypt defense relationship and the strengthening military cooperation between the RoC, Greece, and France. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s recent assertion that “it is absolutely not a coincidence that those who seek to exclude us from the eastern Mediterranean are the same invaders as the ones who attempted to invade our homeland a century ago” underscores such Turkish anxieties of being ‘boxed up’ or put under siege.

Moreover, France’s involvement in the Eastern Mediterranean is viewed by Ankara as a reflection of the French desire to fill the power vacuum created by decreasing American interest in the Middle East and Mediterranean basin as the latter shifts its focus to threats in the Asia Pacific. Examples include the fact that it is deepening its strategic and defense cooperation with the regional actors; sending its warships and planes to take part in joint exercises with Greece and Cyprus; and is venturing its research vessels (together with naval escort) into disputed waters.

It is no secret that the French President Emmanuel Macron has the ambition to restore France’s power and leadership over the Mediterranean, an area that Paris considers as part of its traditional sphere of influence. In the spirit of his predecessors’ projects for the southern European neighborhood, President Macron wishes to set a Pax Mediterranean: a regional Mediterranean order that gravitates around Paris.

But perhaps the bigger judgment here—one that has gone relatively unnoticed so far—is whether the French involvement in the Eastern Mediterranean is only about the gas reserves (i.e., protecting Total’s interests) and curbing Turkish influence in the Eastern Mediterranean; or whether it is instead driven by the wider quest to redesign Transatlantic relations, and, by extension, Europe’s security architecture.

In this regard, the defense pact that Paris signed with Athens in October 2021, hard on the heels of the AUKUS submarine fallout, can be seen as a worrying indication that French plans in the Eastern Mediterranean parallel its efforts to consolidate European military structures such as EUFOR (European Union Force) or the PESCO (Permanent Structured Cooperation). Macron has so far insisted that the Franco-Hellenic deal—first of its kind to originate from within NATO—is not “an alternative to the United States alliance.” His assertion that the move is needed to “take responsibility of the European pillar within NATO” also appears to be in sync with the longstanding U.S. position regarding “burden sharing.”

Yet, it is the subtext that matters here. As one seasoned observer puts it: “Macron is the man who described NATO two years ago as ‘brain dead.’ He will not have changed his mind now.”

It is true that the Trump Administration maintained a rather aggressive attitude toward the Atlantic Alliance, and the realization on the part of France that “Europeans must step up” is not bad news. Having said that, a hastily drawn plan for “strategic autonomy” on the back of ongoing disputes among NATO allies carries the risk of detaching Europe from the United States.

Will Germany Step Up?

Until now, the EU’s engagement with the Eastern Mediterranean was overshadowed by France, Greece, and the RoC, on the one hand, and marked with an unrelenting focus on its volatile relationship with Turkey, on the other.

While Turkey’s actions in the region—and around Cyprus in particular—are seen in many European capitals as both an example of “gunboat diplomacy” and as an act of aggression towards an EU member state, there is also an overall feeling that the EU needs a more functional partnership with Turkey. There is also a feeling that Brussels may also see advantage in forging a new deal with Ankara—one that would legitimize and solidify the arrangements that were stipulated in the Eu’s offer to Turkey of a “positive agenda”—including high-level dialogue—the upgrading of the Customs Union agreement, and the renewal of the 2016 refugee deal.

Germany—now with a new government headed by a new chancellor—could use this opportunity to provide the leadership needed to mend fences with Turkey. Tackling the problems that are found in the Eastern Mediterranean would also stop the dangerous Transatlantic rift in its tracks.

Indeed, more is expected now of Germany and of the country’s new chancellor in foreign policy leadership, after a series of successful diplomatic interventions with Angela Merkel at the helm. For instance, during what became known as the “refugee crisis” too, Germany relied on its extensive societal, economic, and political ties with Turkey to take the lead in EU-Turkish relations and negotiate the ‘refugee deal’ with Ankara. And at the height of the 2020 Greece-Turkey standoff, it was German diplomacy that averted a complete breakdown of relations. It is also well-known that Athens and Berlin clashed at a EU Council meeting when Athens demanded a statement to welcome the eleventh-hour deal it had reached with Egypt, demarcating the two countries’ exclusive zones. The deal was announced much to Germany’s fury a day before the scheduled announcement of exploratory talks between Ankara and Athens that Berlin had brokered.

It is true that Germany’s leadership in the EU is based on the constant interaction and consensus-seeking between Berlin and the other member states, France in particular. But this makes the German leadership in EU foreign and security policy a diplomatic affair, and an important counterweight to France’s often belligerent and hawkish approach. More to the point, France’s involvement in military exercises or more recently in exploration alongside Greece in disputed waters, as well as its push to join the East Mediterranean Gas Forum, has added to tensions at times when Berlin was engaged in talks aimed at reducing them.

For its part, Turkey also knows too that it is ultimately the EU that holds the key to unlocking the Eastern Mediterranean conundrum. Cyprus and Greece are member states, and Turkey itself is still within the EU accession framework. The EU countries have already offered Turkey a “positive agenda,” and there is no reason for Brussels not to continue pressing on with a wider, regional dialogue in the Eastern Mediterranean while advancing cooperation with Turkey within that positive agenda.

Having said that, Berlin and Paris must bridge their differences and work together to advance common EU positions. In this regard, Paris would do well to compartmentalize its differences with Turkey, as the latter has done in other cases. Paris could also use its close ties with Athens and the other EMGF states to emphasize the importance of dialogue. Germany, meanwhile, should continue to use its economic and political leverage over Turkey to ensure Ankara remains committed to its de-escalatory approach, and seek ways to inject a positive dynamic to the overall EU-Turkey relationship that is sorely lacking.

Convening the Conference

The maritime standoff among Turkey, Greece, and Cyprus in the Eastern Mediterranean has already torn through Europe and divided NATO. Paris, for its part, has thrown its weight behind Greece and Cyprus by promoting punitive and escalatory measures toward Turkey in the Eastern Mediterranean. Germany on the other hand, together with Spain, Malta, and others continues to push for dialogue.

This is no time for Berlin to back down. In fact, to ease tensions that exist, avert a new standoff, and start a dialogue, more engagement on the part of Germany may just be what is needed. By taking a leadership role, Germany could renew efforts toward convening an Eastern Mediterranean Conference, which remains the only concrete proposal that both EU and Turkey say could reduce tensions and open a channel for dialogue.

And no matter how ambitious it sounds, if the EU (or, more precisely, its key member states) succeeds in mediating a wide-ranging deal with Turkey on the Eastern Mediterranean through the aforementioned conference, it could help reset the Eastern Mediterranean states’ troubled relations with Turkey whilst also paving the way for sorting out some of the other problems the two sides currently have with each other. Such leadership would, in turn, provide an important way for the EU to flex its diplomatic muscles and significantly contribute to the EU’s broader agenda for re-engagement with the United States.

At the same time, the United States too should leverage its allies on the EMGF (Egypt and Israel, in particular) to arrive at more flexible positions towards Turkey, recognizing its legitimate rights and interests in the region. As Washington pivots to Asia, U.S. President Joe Biden may prefer not to invest too heavily in resolving the Eastern Mediterranean’s maritime disputes. It is also true that relations with Turkey are at a precarious state due to its purchase of Russian S-400 missile in 2017. But Washington should nonetheless be concerned about the possible fallout from the dispute—considering its repercussions for the NATO alliance.

In this regard, American policymakers would do well to recognize that China and Russia will be eager to capitalize on any void and conflict among the allies in the Eastern Mediterranean. Those two powers are already able to maneuver well in the region, taking advantage of the increasing disorder. The hasty notion of strategic autonomy, promoted on the back of the souring of relations with Turkey, also risks turning the NATO into a bifurcated alliance. Turkey remains an important NATO ally and host to U.S. bases; pushing it more toward Russia will bear its own perils.

Now that Turkey has strengthened its position in the Eastern Mediterranean through robust countermoves, it has also adopted a tentative de-escalatory approach. It has indicated that it is open to working with the EU and NATO in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Syria, and Ukraine—showing a good degree of alignment with Western interests. The very recent Turkish request to purchase a fleet of F-17 fighter jets from the United States should also be seen in this same context of reconciliation. On the Mediterranean front too, Ankara has recently reached out to Israel to normalize relations, and to Italy in seeking alternative arrangements that could benefit Turkey economically. Back-channel discussions with Egypt are also ongoing.

The U.S. and the entire EU membership should also embrace this de-escalatory approach, recognizing that a strong Greece-Turkey relationship is in the interest of the entire Transatlantic community. Convening the Eastern Mediterranean Conference at the earliest opportunity would be a good step in the direction of demonstrating that it is possible for the Transatlantic community to solve the disputes that surround the sharing of the Eastern Mediterranean’s energy resources through dialogue. This would truly constitute a “win-win” situation for all parties.