Stephen Lew, DPhil (Oxon) is a Senior Fellow at the Council of Presidents of the UN General Assembly and Director of a nascent think tank, Qonduct Institute, focusing on responsible governance and applications of technologies such as AI towards advancing the Sustainable Development Goals. He served as a Senior Advisor at the federal government of the UAE, as an academic at premier institutions, and as a quantitative analyst at various financial institutions and collaborated with several Nobel laureates throughout his career. Dr. Lew can be reached at [email protected].

Stephen Lew, DPhil (Oxon) is a Senior Fellow at the Council of Presidents of the UN General Assembly and Director of a nascent think tank, Qonduct Institute, focusing on responsible governance and applications of technologies such as AI towards advancing the Sustainable Development Goals. He served as a Senior Advisor at the federal government of the UAE, as an academic at premier institutions, and as a quantitative analyst at various financial institutions and collaborated with several Nobel laureates throughout his career. Dr. Lew can be reached at [email protected].

Much has been said about the existential threat that artificial intelligence (AI) poses. Efforts are being made, however, to encourage positive use of AI as well. AI is at something of a sensitive inflection point where the proper use and governance of it could bifurcate into two radically different lobes, to use a non-linear dynamics metaphor.

In this essay, I aim to make the argument that youth could play an important role in determining which lobe AI might evolve towards. On the one hand, youth could be a formidable force in harming society by way of, for example, AI-enhanced hacking if their empathy and sense of societal responsibility were unchecked, as they might be unaware or even nefariously pleased by any negative societal impact of their actions; on the other hand, they could ensure that the development, deployment and applications of AI are for the good of society, thereby ‘saving AI.’ However, this would require that empathy in general is properly instilled and they have a greater sense of awareness about the consequences of their actions in the cyber and AI realms.

I draw upon a mathematical concept known as “positive definite,” i.e. certainly not negative, and not even neutral, numbers (x > 0), if we were to quantify societal impact of one’s actions: it is precisely this variety that the shape of youth’s involvements in AI should take. Imagine a whole generation of humanity who are both aware of the directions of AI evolution and are intent on ensuring that the direction is positive! With that in mind, I shall make the following observations:

-

AI governance and cybersecurity need to be considered holistically: one of the key manifestations of poor AI governance would be cyberattacks, and well-governed AI might greatly benefit mankind.

-

Cyber-attackers are often young people, and AI tools are making it easier to make these perturbations (who see it as sources of amusement, means for getting attention, puzzles to solve and so on) with often unforeseen consequences.

-

Alongside technological defenses against such attacks, it would be incumbent upon members of society at various levels to imbue greater sense of empathy in general, and specifically, raise awareness about the potential consequences of these attacks.

-

Accompanying the overall empathy education above, there are specific programs and training regimens that are specific to AI governance and cybersecurity. It is incumbent upon educational institutions, state actors and multilateral bodies to consider and implement them.

-

It has often been said that humans are the “weakest link” when it comes to cybersecurity. If or when youth are in fact more empathetic and aware of the consequences of their actions, this would mean that humans become the ‘strongest link’ in AI governance and cyberdefense. Youth might in fact turn their talents towards applying AI for the good of society and nature, the combined impact of which could be tremendous indeed.

A Holistic Approach to AI Governance & Cybersecurity

Some of the most pressing and complex challenges in the digital realm are multifaceted, involving both AI governance and cybersecurity. If AI were to go amok, its attack would assume some form of cyberattack in the first instance, and cyberattacks are being increasingly facilitated and augmented by AI. The AI revolution is well on its way in many aspects of life, this includes the landscape of cybersecurity, enhancing both defensive and offensive capabilities in unprecedented ways. In other words, artificial AI and cybersecurity are increasingly becoming inextricably intertwined.

The potential of AI to detect, predict, and respond to cyber threats is immense, but so is its capacity to be exploited for malicious purposes. Thus, we need to consider the governance of AI more holistically by augmenting the theme that is inclusive of cybersecurity. Understanding and navigating these dual aspects is a prerequisite for any meaningful and robust governance of AI.

Examples of AI facilitating cyberdefense capabilities include cloud-based and AI-enhanced software tools that detect threats behaviorally and statistically, rather than relying on raw dictionaries of viruses, malwares, ransomwares, and other codes that pose as threats. Such dictionaries have inherent limitations in having to keep up with the speed at which the threats are generated, which is being increasingly facilitated by large language models-based AI tools.

Enhanced by AI or not, such cyberdefense tools are not fool-proof, and there are times that an IT network does not even require an external attack for it to malfunction at a spectacular scale. If I were to write that some software glitch caused worldwide disruptions at hospitals, airports, banks, broadcasting services, and so on, one might not find it particularly believable. It may seem like a scene straight out of a sci-fi movie. After all, a scene like that is something of a staple from such movies where the mock BBCs and CNNs of the world would cover such global disruptions.

At the time of writing, exactly this type of global disruption happened: a cybersecurity provider for a large tech organization was doing a routine update and the patch had a “glitch” in it. That glitch conflicted with the operating system (Windows 11), and all the goods and services that relied on the operating system suffered outage worldwide.

Now the ‘fortunate’ thing about it, so to speak, was that it was not a deliberate cyberattack but a ‘glitch’ of a third party, ironically, by a cybersecurity software provider. However, the effects are not too dissimilar in terms of disruption and the loss of productivity from a ‘normal’ cyberattack. An aspect of this glitch that might not be as fortunate could be that it may well serve as a fodder for inspiration for a potential cyber-attacker or a hacker. After all, they have identified a useful attack vector which they might be able to exploit from now on.

On the offensive front, there are myriad possibilities where AI facilitates such attacks, e.g. the aforementioned large language models that are dedicated to generating harmful codes and phishing scripts for gaining unauthorized access to secure facilities, interfere with elections, or destabilize financial markets. When it comes to deliberate attacks, there are a plethora of real-life cases where critical infrastructures were hacked into and caused significant damage, facilitated and augmented by the aforementioned tools.

An added ‘bonus’ with AI is that AI can have agency and may launch attacks out of its own accord. It does not need to be ‘malicious’ as we would attribute to it, it could simply be an outcome of an optimization calculus as far as the AI could surmise. This gives all the more reason to consider AI and cybersecurity as an inextricable whole. By extension, we should eventually consider the kinetic realm also as part of the AI-cyber ecosystem in that it often only takes a small perturbation to wreak massive, tangible, kinetic havoc in the system.

The Havoc-Wreaking Youth in Popular Culture and Real Life

As early as the 1980s, hackers hacking into critical infrastructures have become something of a staple in the sci-fi film genre, and many of the said hackers tend to be youth, often just teenagers still in school. There was one such movie in the 1980s, where the protagonist thinks that he hacked into some type of a game but it turns out that it was the Pentagon’s nuclear launch network and nearly launches the U.S. nuclear arsenal and narrowly misses.

Another movie in the 2000s features a young hacker who gets ‘recruited’ by law enforcement personnel so as to thwart a series of cyber-attacks on citywide critical infrastructures. At one point, the recruited hacker refers to a mythical cyberattack protocol to which he refers as “firesale,” as in “everything must go” by attacking first the transportation, financial network, utilities, nuclear and other critical infrastructures—anything that is networked and run by computers, which today is “pretty much everything.”

Yet another scene is from a well-known UK spy franchise, where the new Quartermaster (Q) introduces himself to James Bond. Bond cannot believe that he is the new Q, not because Q is not wearing a labcoat as Q surmises, but because he is just a young man. After some exchange about neither age nor youth guaranteeing either competence or innovation, Q goes to say “I hazard a guess that I could do more damage on my laptop in my pajamas before I finish my first cup of early gray [tea] than you can on the field in an entire year.”

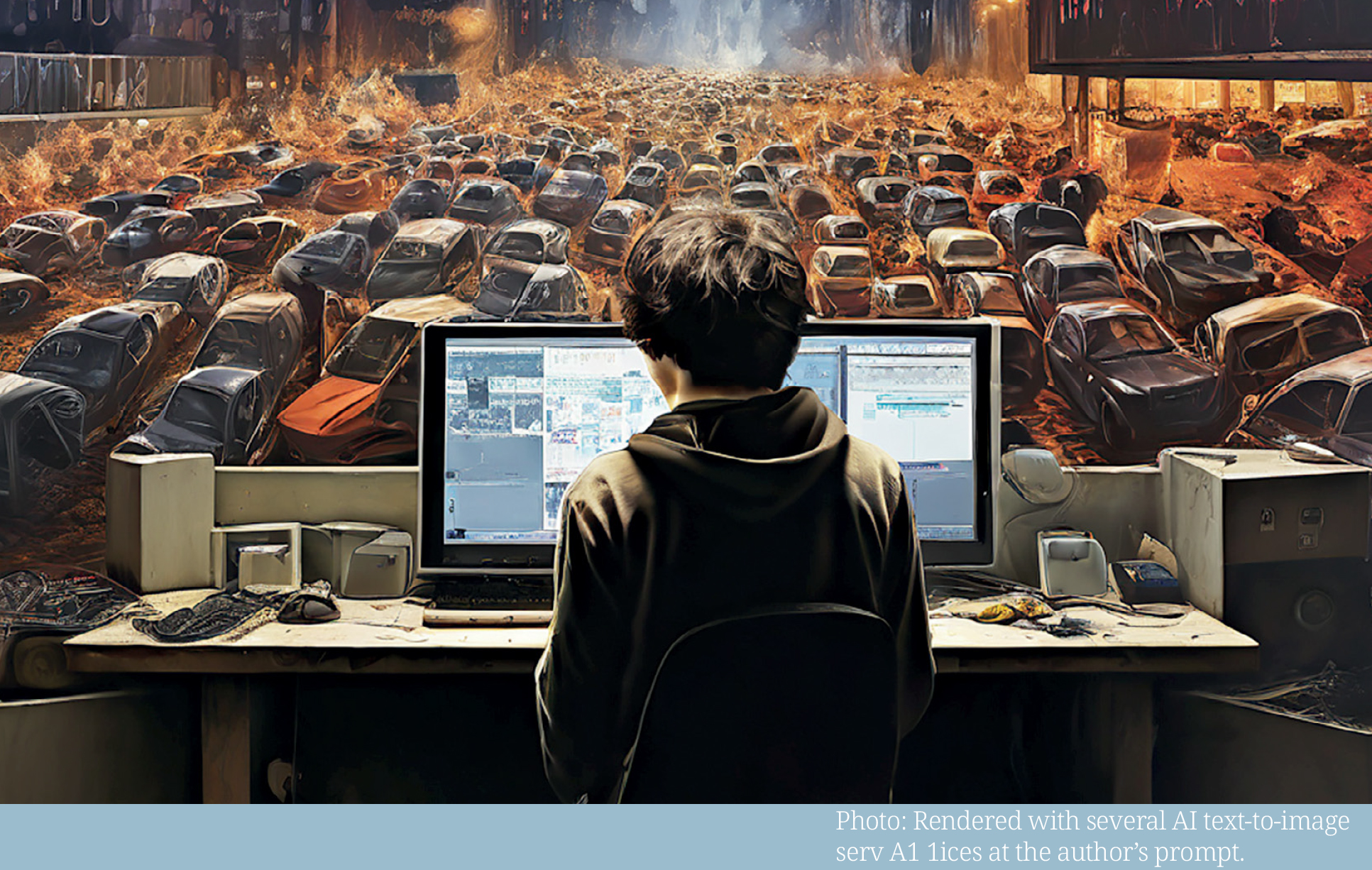

A youth, still a teenager, casually hacks into a traffic control network for amusement, with AI augmenting his abilities to do so.

Figure 1. A youth, still a teenager, casually hacks into a traffic control network for amusement, perhaps to brag about his exploits, or to see if he could do it. The helping hand provided by AI is augmenting his abilities to do so. The youth may be entirely oblivious of, apathetic towards, or even draw some enjoyment out of ‘beating the system’. A whole traffic of cars driving into each other and piling up at a busy intersection would be but one of the potential scenarios [Source: rendered with several AI text-to-image services at the author’s prompt].

If the reader gained an impression that such youth-driven cyberattacks are purely the stuff of fiction, the reality is not quite so: some of the hacker groups that have carried out some of the most publicized (and damaging) cyberattacks in recent history are composed of young people, those that are aged 16-21. The “mastermind” of one such group was not older than 16 years of age by the time he was apprehended, after they had hacked into a well-known chipmaker, telecoms company, electronics manufacturer, and so on. The motivations of hackers and hacker groups differ, but often it is for “amusement” or some type of “mental challenge,” or in some cases, to seek attention.

Empathy as Crucial Part of Education

It is one thing to enact a small action and the consequences being much larger in scale only, as in start a small ripple and it becomes a larger ripple, qualitatively identical, but larger only in size. It is also that the consequences tend not to be sequential, predictive, or in mathematical terms, ‘linear.’ As the American meteorologist Edward Lorenz discovered in the early 1960s, a complex system like the weather is highly sensitive to initial conditions where the system evolves in a non-linear manner. Dubbing it the “butterfly effect,” a phrase which has entered the daily vernacular, he discussed the idea that the sensitivity to initial conditions and the non-linear subsequent evolution of the weather system would be such that if a butterfly flaps its wings in China, it would cause drastic changes in weather in the U.S. several days thereafter.

It is not just in weather that this type of divergent consequences upon one’s small actions, which renders long-term forecast of its evolution nearly impossible, occur. Indeed, life in general is like this, not lending itself to an obvious assessment of the trajectory of one’s actions. Effects can be non-linear, multiple, exponential in any which direction. Thus, it behooves the individual to act in a manner that has, at least, the best intentions - when in fact, even this might generate unintended consequences. What if one sets out to actively cause harm? There really is no justification for this. In other words, the action one takes needs to be positive definite, at least in its intent. And even then, due to non-linear effects and the systems design itself, there will be unintended consequences. This is perhaps the key idea that the young people need to understand and institutions need to do their best with which to imbue them.

So what might engender such a positive definite turn of intents? What is required, perhaps above all, is education so as to instill a stronger sense of empathy from an early age. Youth need to be conscious of the idea that it is “not cool” to hack into things, they can literally ruin or destroy lives, that “it is not a game” and that an action like hacking has real-life and sometimes catastrophic large-scale consequences. At this stage, the education would not be about governing AI or cybersecurity per se. It is a larger, perhaps a more philosophical question of how do we imbue our young people with a stronger sense of responsibility bearing towards society and nature at large so that they stop and think twice before they take on a ‘challenge’ from their peers, or indeed, impose challenges upon themselves?

Karl Marx proposed that one of the most grievous failure modes of capitalism is what he termed Entfremdung, or, “alienation”. Although not the context in which this was intended, it might be that the resulting damages of the cyber-attacker’s actions are ‘alienated’ from the perpetrator. In the critique of capitalism, the laborer is alienated from various aspects of the means of production (e.g. positive effect, human potential, and mental challenge) or the product itself.

In the cyberattack context, often the attacker is alienated from the damage they inflict, or in an ironic sense, the “product of his labor.” The attacker often sees it as a source of amusement, some type of puzzle, challenge, or game. They might be skilled at exploiting human vulnerabilities, creating and disseminating malware, or launching DDoS attacks, but they often do not witness the real-world consequences of their actions. They might not see the financial losses, the disruption of services, or the emotional distress caused to victims. This detachment from the impact of their actions can contribute to a sense of alienation.

The attacker is alienated from the human victims as well as other humans at large. As pointed out above, cyber-attackers derive satisfaction from overcoming technical obstacles, demonstrating their skills, and outsmarting security systems. This focus on the technical challenge can lead to a detachment from the human implications of their actions. Furthermore, they often act in isolation or by communicating with others via pseudonyms in order to hide their identities on online forums or underground communities, fueling further sense of isolation and alienation and corroding their sense of empathy and ability to empathize with other humans.

Cyber-attackers alienate themselves from their own potential. Had they cultivated meaningful social connections and put their computer skills to positive use, they might have been able to make positive contributions to society. Instead, some of the most skillful hackers get locked up, never to be allowed to go near computer terminals or access the Internet ever again.

In a way it is a reverse process of Entfremdung we discussed above, where the product of labor and means of production are alienated from the part of the laborer. It could be that a conscious effort to de-alienate or familiarize the laborer with his or her product and means of production could raise awareness about the societal implications of their products, by corollary.

In other words, the individual would own their ‘products’ by understanding and being cognizant of the potential impact of their actions (whether it be a cyberattack or a positive application of AI); rather than launching an attack, they would seek to forge meaningful connections with other humans so as to make positive contributions to society, thereby fulfilling the potential afforded by their prodigious computing-related skills.

Linking Empathy with AI & Cyber Governance

As important as it is to imbue youth with greater empathy and sense of social responsibility in general, the rubber has to meet the road, if we are to focus on AI governance and cybersecurity. Furthermore, it is incumbent upon institutions (whether it be academic, national, multilateral, and so on) to look into implementing programs that might systematically and institutionally do the imbuing within the AI and cybersecurity context.

Academic institutions such as primary and secondary schools as well as institutions of higher learning could all contribute towards raising awareness about the consequences of abusing AI. For example, part of the curriculum could be dedicated to introducing examples where they discuss real-life consequences of cyberattacks enhanced by AI. At a multilateral level, the United Nations, through initiatives like the Summit of the Future, has a unique opportunity to lead this educational transformation. While the UN has pursued the drafting of the Global Digital Compact and the resolution on cybersecurity, policies and regulations typically tend to lag behind technological developments.

As a practical matter in addressing youth directly, some strategies which educational establishments, governments around the world and a multilateral body such as the UN could implement to foster a greater sense of societal impact and empathy among youth in AI governance might include hands-on workshops, hackathons, joint research projects so that young innovators have opportunities to come up with applications of AI towards pressing global challenges such as climate change, species conservation, healthcare outcomes and socioeconomic inequalities. Resources such as online courses on responsible AI and talks by experts on AI ethics, governance, and policymaking and small research grants could facilitate the above. “Bug Bounty” Programs where youth could engage in finding bugs and vulnerabilities of simulated networks could also be held.

The idea in all cases would be to a) let youth associate the act of applying AI towards something, including accessing various networks, with something ethical and responsible, and b) to let them experience solving challenges intentionally and explicitly for the good of humanity be rewarding, rather than harming humanity.

From the Weakest to the ‘Strongest Link’

It is said that of the many attack vectors in cybersecurity, the human often is the “weakest link.” By converse, turning the table on this occurrence that is often observed, by addressing the youth and imbuing them with a sense of responsibility for their actions, they could perhaps be the ‘strongest link.’

There are avenues through which a cyberattack could occur: it could be the DDoS attack, worm or a virus, zero-day exploits, and so on. Every one of these has been and can be exploited by a cyber-attacker. However, often nothing beats fooling the hapless insider by so-called “social engineering,” which stands as one of the strongest attack vectors in cyberattacks. In other words, as has been often said, humans often present the weakest links.

They come in several flavors: they can be unwitting accomplices to gaining unauthorized access to something via an attack known as “pretexting” where the attacker creates a credible story or scenario to convince someone to provide them with sensitive information. Even many of the more ‘techie’ attacks such as the worms or ransomware are activated by the human in the first place, e.g. the human clicking on the suspicious link and downloading them via processes such as phishing. Or the attackers can be ‘insiders’ themselves of an organization, such as employees at an intelligence agency or military stealing classified information and leaking or selling them for financial gain.

If we were to have done that job correctly, we might just be able to get our youth to be more socially conscious and responsible about their actions. What might the converse of the weakest link look like, within the AI and cybersecurity context? One possibility might be that the young people would not hack into things for “amusement” in the first place. If they did, it would be to alert the ‘powers be’ of the said infrastructures, for example. They would be far more interested in using AI for the net good of mankind. The whole narrative of young people as hackers to harm society could change into young people that use technologies as a force for good, thereby contributing towards averting the existential threat of AI and, in a manner of speaking, ‘save’ AI.