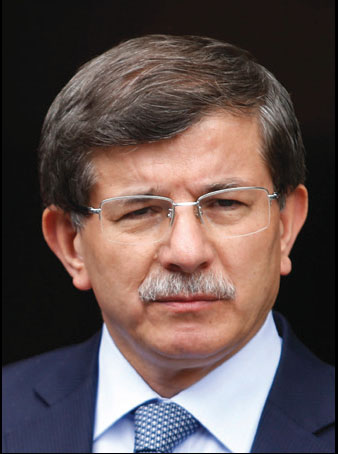

Ahmet Davutoglu is a former Prime Minister and Foreign Minister of Turkey. This essay is adapted from a chapter in his latest book, Systemic Earthquake: Struggle for World Order (2020) and is used by permission. You may follow him on Twitter @A_Davutoglu_eng.

Ahmet Davutoglu is a former Prime Minister and Foreign Minister of Turkey. This essay is adapted from a chapter in his latest book, Systemic Earthquake: Struggle for World Order (2020) and is used by permission. You may follow him on Twitter @A_Davutoglu_eng.

One of the most significant consequences of the fragilities created in national, regional, and global structures by the ongoing systemic earthquake process in geopolitics is unpredictability. Whatever the subject matter of these successive and dizzying seismic shocks, and at whatever level they occur, they do not facilitate our ability to make future projections.

The surprise effect and unpredictability mostly make an impact on the psychology of decisionmaking processes. Actors unable to make future projections and see far ahead are induced to accumulate power and take precautionary measures according to negative scenarios. This leads in turn to the weakening of the value dimension of national, regional, and global mechanisms and the proliferation of a general sense of pessimism.

Possibilities and Ideals

Looking at the general trend, we may state that we are walking towards the possibility of three different futures. The first possibility is a state of global chaos to the extent that the inability of actors to develop a common framework will leads to the disintegration of fragile structures in the natural course of events, and a large-scale and comprehensive war resulting from rivalries between powers taking account of this disintegration.

In this projection, which means a repetition of the scenario between the two World Wars, tensions and the effects of seismic shocks progressively intensify and a new global war becomes inevitable. In such a scenario, a new world order will only be established after this war, shaped around the principles adopted by its victors.

The second possibility is a global autocracy involving the establishment of an autocratic order or orders high in the power to control and low in participation levels by a group of countries or leaders exploiting the struggle to escape from an escalating and spreading state of chaos and the psychology of pessimism, and using the extraordinary possibilities presented by the technological communications revolution to bring their own populist and exclusionary claims to life.

The globalization of an authoritarian tendency of this kind, buttressed by a “worst state is better than no state” argument favored by traditional state structures to demonstrate the drawbacks of chaos and the importance of the continuity of order, means the delayed realization of George Orwell’s 1984 conceptualization. This scenario could occur as a single autocratic Leviathan, or the creation of a widespread and hierarchic order by a number of Leviathans resembling one another.

The third scenario, which we might call global democracy, could be the product of the motivational will of policymakers, politicians, thinkers, and opinion leaders with the backing of society, based on the centuries-long and bitter experiences of humankind and bestowed with the participatory virtues of shared values.

The sole prerequisite for such a participatory, embracing, and inclusive approach on the national, regional, and global scale is that it is realized this time without entering a new world war.

The truth is that when we examine the available data and the general stance of today’s politicians and policymakers, a realist would predict a future in a space where there is some kind of combination of the first and second scenarios. However, when asked what the scenario should be, the same observers would point to the third.

We thus find ourselves once again facing the most time-weary problematic of all, stemming as it does from the ideal/real, theory/practice dichotomies of humankind’s political quest down the ages. When our mental balance is weighted to the “real world” end of the scale, we are led to waiting for our inevitable fate, while when the balance swings to the ideal end of the scale we find ourselves at risk of being trapped in the idealist boundaries of our imaginary world. The first stance would detach us from our will, the second from the realities we experience. The state of shock induced by successive earthquakes threatens to imprison our will; an escape from existing realities, our mind. Therefore, what we need to do is release ourselves from the psychology of pessimism, establish a healthy balance between a normativism attached to reality and a realism that takes values into account, and then to create a new projection of order within the harmony of this balance.

In order to elicit a new order’s doctrinal basis, one needs to define the fundamental principles that will constitute the intellectual substructure for international, regional, and national-scale endeavors and guide practical applications. In this essay, we shall first determine the principles of such a projection of order, before moving to an initial discussion of the prospects for adapting these principles to the national, regional, and global structures, and what needs to be done.

The systemic earthquake process in which we now find ourselves calls for principles that are processual rather than piecemeal, integrative rather than disintegrative, feasible rather than hypothetical. Based on the experiences of the post-Cold War era and the requirements that have surfaced, we may assert the existential nature of five key principles in the reconstruction of national, regional, and international order: inclusiveness, internal consistency (the harmonization of values and mechanisms), interest optimization (the optimization of individual and common interests), implementation (of the power structure), and institutionalization.

The first two of these principles (inclusiveness and internal consistency) define the idealist foundation, the following two (interest optimization and implementation) the realpolitik framework, while institutionalization provides the bridge and transitivity between them. Experience shows us that while an approach defined by ideal values alone struggles to find implementational grounding, a realpolitik that is detached from values undermines its doctrinal grounding. A new understanding of order is attainable by overcoming the idealism-realism tensions experienced throughout human history. In this regard, the extraordinary communications potential that has now reached every level of society presents encouraging opportunities as well as serious challenges.

Inclusiveness

I believe that when we consider these principles—I call them the Five Eyes (as in the letter i)—one by one, the principle of inclusiveness is of primary importance, because any order that is not integrated into the system and fails to include all actors and elements—be it on a national, regional, or international level—cannot be effectively run or sustained. Every actor excluded from or rendered inactive by the order either seeks out an alternative order in alliance with similarly excluded parties, or becomes an element of potential chaos.

This principle has shown its impact not only in the modern era but at all stages of history. A look at the traditions and orders of the great empires shows that the Germanic tribes who were not included and internalized in the Roman order first disrupted this order and were then influential in establishing the Holy Roman-German order, which did include them. The Protestant princedoms excluded from the Holy Roman-German order shaped the course of history that led to the chaos of the Thirty Years War and then to the Westphalian order.

This phenomenon also finds reflection in the geography of the Middle East with the leadership of the non-Arab Muslims (Mawali), who were unequally treated in the clannish asabiyyah-based Umayyad order, in the emergence of the Abbasid order.

The non-Arab elements that had been excluded from the system for a period then took control of it, thus positioning themselves at the center of the political order. Ibn Khaldun, who had placed the concept of asabiyyah at the heart of his theory of political order, described this change as follows:

Then, the days of Arab rule were over. The early generations who had cemented Arab might and founded the realm of the Arabs were gone. The power was seized by others, by non-Arabs like the Turks in the east, the Berbers in the west and Christian Europeans in the north.]

Thus, for instance, the concurrent use of the four titles symbolizing the past orders of the classical age by Ottoman sultans who had drawn lessons from this historic experience (Caliph/Islam, Khān/Tūrān, Pādishāh/Iran, Caesar/Rome) was designed to emphasize their status as the continuation of the great orders of the past and therefore that all these different elements had legitimate authority. In this way, they symbolically demonstrated that their own orders had internalized and integrated all the communities that had previously been under the domination of different political traditions. As Amy Chua of Yale University’s Law School underlines, “the Ottomans derived great benefits from their strategic tolerance Indeed, when the Ottoman State lost its inclusive capacity, it initiated a process of chaotic division.”

This dialectic of inclusiveness also played a significant role in the dissolution of colonial empires, which by their natures observed no such principle or purpose. The main impetus of the independence movements in India and Algeria was the incapacity of the governing elite, which remained differentiated from the indigenous society in every respect, to incorporate an inclusive philosophy into their governance. This also applied in the case of the apartheid regime in South Africa, one of the last representatives of the logic of exclusionary colonial governance brought about by a lack of inclusiveness. And once again, it is the inability to be inclusive that lies at the root of the existential tensions in Israel, a state founded on a colonial rationale.

This same dialectic, which has defined the fate of attempts to establish new orders throughout history, also applies to the nation-states that constitute the building blocks of today’s international order, and to the regional and international struggles for order that have shaped them. Nation-states that had been sustained by static external balances associated with the bipolar Cold War structure faced a severe test of their inclusiveness when these static balances began to lose their hold. States pursuing an inclusive approach embracing the entire range of identities within their boundaries as part of their concept of citizenship passed this test to enter the new era in a stable condition while those who were unable to do so fell prey to a chaotic course marked by division and conflict, as we have seen in the cases of Yugoslavia, Iraq, and Syria.

The inclusiveness principle influences more flexible regional structures as well. It is true that the EU has scored successes through its capacity for inclusiveness towards Central and Eastern European countries after the Cold War. Yet its postponement of Turkey’s full membership on the pretext of issues like Cyprus that are not directly related to Turkey, and its promotion of countries that are further from fulfilling EU economic and political membership criteria than Turkey based on an exclusionary resistance to Turkey’s accession process, have exposed weaknesses in the EU’s capacity for inclusiveness, as well as laying the ground for Turkey to develop a psychology of distancing itself from the EU.

If it had been possible to complete this process of inclusiveness in the first decade of this century before the global economic crisis and the Arab Spring, the course of history would doubtless have taken a different path; neither the Islamophobia now growing in the EU nor the anti-European sentiment now growing in Turkey would have found such fertile ground in which to flourish.

For the international system overall, the most serious sustainability challenge stems from weaknesses in its capacity for inclusiveness. The profound differences in structure and authority between the UN’s representative and decisionmaking bodies (the UN General Assembly and the UN Security Council, respectively) constitute a striking manifestation of this weakness.

The inclusive nature of the General Assembly is rendered virtually meaningless by the oligarchic decisionmaking mechanism resulting from the veto power of the five permanent members of the Security Council. For example, the veto of a single country on the Security Council renders decisions taken by the overwhelming majority of human society on the Palestinian issue entirely symbolic and bereft of any scope for implementation.

The most recent example of this was on stark display in the Security Council and General Assembly procedures in the wake of President Trump’s declaration of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel. Similar situations have arisen as a result of other countries’ veto powers, especially with respect to the Syrian crisis.

In terms of the sustainability of the international order, the frailty of inclusiveness in the international system is currently one of the most fundamental challenges facing not only the UN but the system as a whole. Today, the most significant obstacle to any future efforts to establish order are exclusionary methods and approaches in the international system and the geopolitical tension they generate

To be able to establish a new, sustainable order we should never forget this basic lesson of history: excluders get excluded.

Internal Consistency

The second principle directly related to inclusiveness is internal consistency. The idea and implementation of order harbors within it a condition for internal consistency. No order can be formed and made sustainable by a concept or structure lacking in internal consistency.

There are two minimum conditions for achieving internal consistency: the existence of an internally consistent system of values jointly espoused by the order’s actors, and mechanisms to ensure the practical implementation of these values. Even with an agreed system of values, in the absence of a proper mechanism they will remain abstract ideals without the capacity to form the philosophical, legal, and political substructure from which an order is constituted. On the other hand, when there is no agreed system of values, or when the essence and influence of these values is lost, any kind of mechanism turns into an interest-dependent tool.

Today, both the national and international order face weaknesses arising from a severe lack of internal consistency on both counts. First of all, values have been hollowed out by weaknesses in implementation mechanisms while the legitimacy that these values bestowed on the international order was undermined. Every value violation that occurred in front of the international community stretching from the genocide perpetrated in full view of UN forces in Srebrenica in 1995 to the use of weapons of mass destruction in the Ghouta area of Damascus in Syria in August 2013 served to destroy the meaning of those values.

In spite of the UN Secretary-General’s clear call in stating that “the international community has a moral responsibility to hold accountable those responsible and for ensuring that chemical weapons can never re-emerge as an instrument of warfare,” in the latter case no sanctions were applied against those who had committed war crimes in violation of international law and values. The apathy of the international community laid the ground for the subsequent and frequent repetition of these crimes. The failure to protect shared values has hollowed them out and led to a lack of internal consistency that has shattered the very soul and spirit of the order.

Moreover, the international principles and conventions that are primarily the reflection of shared values are applied selectively. This selectivity is generally shaped by the national preferences of the P5 countries.

For example, the United States, which with an international coalition has fought the Daesh terror organization, sees no issue in arming the YPG, which is organically linked to the PKK, a group the United States itself defines as a terrorist organization. By the same token, Russia, which legitimizes its military intervention in Syria through the thesis that it was invited in by the UN-recognized government of that country, is also able to grant itself the right to support separatist groups against the UN-recognized government of Ukraine.

The same P5 members that call on all countries to comply with the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT) and the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) and, if necessary, apply sanctions to enforce compliance, turn a blind eye to Israel’s remaining beyond such conventions. On the other hand, the nuclear weapons states, led by the United States, insist on compliance with non-acquisition of nuclear weapons while failing to comply with the Article VI obligation to seek nuclear disarmament in good faith, an obligation unanimously confirmed by the International Court of Justice in 1996.

These value-action and value-mechanism contradictions are also apparent in the internal structure of a number of nation-states, leading to problems of legitimacy. The ethnic, religious, and sectarian discrimination seen in various countries claiming to be founded on principles of common citizenship and the values of the rule of law constitutes one of the most significant risks to the sustainability of the nation-state order.

To summarize: the double standards present at every level today erode shared values and promote a lack of trust and confidence in the existing order. This state of distrust and insecurity leads to a “jungle order” in which everyone takes a stance based on their own interests and power rather than shared values, a path that only serves to intensify the systemic earthquake.

What is needed is a reappraisal of the existing conventions and body of knowledge that comprise the foundations of our shared values in a way that responds to new challenges. The attainment through such a reappraisal of a totality to create internal consistency in an updated system of values through appropriate mechanisms is one of the essential conditions of the struggle for a new order.

Interest Optimization

It is in the nature of the national and international order that concerned actors struggle to maximize the realization of their own interests. Shaped by all kinds of negotiation, reconciliation, tension, and war, the flow of history emerges in the area of competition and rivalry of these maximization struggles. Envisaging a new order that will eradicate this area is unrealistic.

Yet the existence of a competitive environment of this kind does not necessary entail a state of value-destroying chaos. Values determine this environment’s rules, define its boundaries, and fix its points of reference. The relationship between an idealist approach that highlights values and a realism based on the irreconcilability of conflicts of interest is itself determined by the relationship between the naturalness of a differentiation of interests and the rule-making characteristic of values.

When values lose the power to determine the rules of competing interests, rivalries first turn into tensions, then escalate into clashes, and ultimately wars. The substance of national and international order is measured by its capacity to prevent such escalation. In environments where order is functional, this area of competition is determined by peaceful means with diplomatic tools. In the transition from a state of order to one of disorder, the rules defined by these values first become blurred, then lose their effectiveness, and finally start turning into a state of nature in which the concept “man is wolf to man” (homo homini lupus) prevails.

The key point here is to create an environment that optimizes mutual interests by keeping competing interests within the scope of rational negotiation. The performance of national and international mechanisms in terms of establishing and conserving order is about ensuring this approach and environment, guaranteeing the sustainability of the order by providing the opportunity for rational negotiation that optimizes individual and common interests.

There are three options in the struggle to maximize interests, each of which has a different impact on the course of the competitive environment in the national and international system: the win–win, win–lose, and lose–lose options.

When the concerned parties achieve a win–win optimization of interests as a result of rational negotiation, confidence and trust in the rules grows and everyone experiences the satisfaction of getting their fair share under the order’s arbitration. Every time this option is repeated, the order consolidates itself and its sustainability is boosted. The success story of every diplomatically achieved resolution has a positive impact on the functioning of the order and the performance of its mechanisms as a growing atmosphere of optimism comes to fruition.

When the win–lose option recurs, the consistently losing side starts losing trust and confidence in the order. And when this loss of trust leads to alienation from the order, the losing party tends to bypass the rules it believes operate consistently against its interests. On the other hand, the winning party starts to develop a cavalier attitude to the binding nature of the rules, an attitude based on a psychology of excessive self-confidence and superiority and seeing the optimization of its own interests as a natural right without even feeling the need to negotiate with the other side. Thus, as a result of the winning party’s excessive self-confidence and the loser’s loss of confidence and trust, a tendency not to conform to the order’s values and the system’s rules manifests itself to such an extent that any shared belief in the sustainability of the order is destroyed.

In lose–lose cases, the order’s gravitational force begins to fade. The extensive recurrence of this situation entices the parties either to relapse into a state of disorder or to advocate a new set of rules that they believe will maximize their interests. The increasing occurrence of this situation in national orders is observed in fragile states where de facto areas of dominance take shape. Nation-states that constitute the center of power of the common order thus begin to unravel, leading to the emergence of a chaotic process that also has an impact on the international order. By the same token, the recurring “non-success story” of the lose–lose option in international relations first shakes trust in the order and then leads to the domination of an ever-expanding psychology of pessimism over the process.

When we look at the actual functioning of the national and international order today, we observe that the first (win–win) option is the exception, the second (win–lose) is dominant, and the third (lose–lose) is on a progressively rising trend. This has led to a growing sense of pessimism about the functioning of the current order as actors lose hope that they will emerge as beneficiaries. Such a state of pessimism and insecurity drives every actor to act unilaterally to protect its own interests to the extent that its power permits.

Attempts to optimize interests through unilateral action rather than rational negotiation first stretch the rules, then render them meaningless, and ultimately invalidate them. We may discern four phenomena as both cause and reflection of this spreading sense of insecurity and pessimism.

The first phenomenon is the almost total absence of any success story in terms of reaching final resolutions, in spite of the accumulation of dozens of problems in the wake of the earthquakes that have shaken the world in the quarter-century that has passed since the end of the Cold War. Efforts to reach such resolutions have achieved either provisional ceasefires (Nagorno-Karabakh, Abkhazia, Ossetia, et al.), fragile states of peace (Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo), or limited conjunctural deals (the Iran nuclear deal).

Concerns that fresh chaotic developments might take place even in the event that conflicts are somehow halted, and that one side might act to attain a win–lose position to its own benefit if appropriate circumstances arise, only increases fragility in the order.

The second phenomenon is the prevailing sense that parties have been treated in a discriminatory manner in efforts to resolve crises arising from conflicts of interest in the operation of the international order. And in a manner of speaking, the theoretical value that “all parties are equal in the international order” has become a case of “some are more equal than others” when it comes to practical implementation.

In negotiations the “more equal” side is protected and rules are interpreted in such a way as to protect that side’s interests. This leads the protected party to disengage from agreement until such time as a solution that maximizes its own interests in absolute terms is fashioned.

Two examples help illustrate this second phenomenon: that of the Israeli-Palestinian peace process and the Cyprus issue.

The most striking case of this kind is the inability of the Oslo Process, launched with the hope that the Palestinian people would finally be free to live in their own country, to achieve the objectives it set itself at the outset of a process that began a quarter-century ago. In spite of the fact that the Declaration of Principles (Oslo I) clearly refers to “a transitional period not exceeding five years, leading to a permanent settlement based on Security Council Resolutions 242 and 338,” this transitional period has not been completed in the intervening twenty-five years; nor is it expected to be completed in the foreseeable future.

The fundamental reason for this lies in the fact that the situation described is not one in which the two parties have an equal negotiating position that might force a win–win position. Underlying this is one party’s belief that it has the support of a veto that will prevent the imposition of any penalty or sanction come what may, as well as that same party’s exploitation of all the advantages of being a state. Israel’s knowledge from the very beginning that any decision or resolution contrary to its interests will be vetoed by the United States has encouraged that country to say ‘no’ to any solution that fails to maximize its own interests while miring the Palestinian side in an ever-deeper sense of pessimism and despair.

The trauma inflicted on the objective functioning of the international order in this process has spilled beyond the Palestinian side, having led to an intensification of mistrust in the international system first in the Middle East and then in the Muslim world as a whole. The effects of the psycho-political trauma resulting from Muslim societies’ belief that they have been marginalized from the international system are manifest in almost every field.

A similar imbalance in the Cyprus issue—of all the problems left over from the Cold War, it is the closest to a lasting solution—has prevented the emergence of an otherwise feasible success story. Following the successful conclusion of rational negotiations under the coordination of then-UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, the permanent peace settlement signed by the parties in Bürgenstock in April 2004 was approved by the Turkish Cypriot population but rejected by the Greek Cypriot population in a subsequent referendum; a potential success story was stillborn.

In the case of Cyprus, a successful negotiation process took place with the contributions of all parties, especially the UN, with a view to achieving a resolution of a Cold War-era legacy issue—both for itself and as a precedent and example for numerous other frozen crises. My own cold-blooded assessment of events—as someone who participated in negotiations in advisory and ambassadorial capacities—from the past to the present day is that the most significant factor in the ultimate failure of this process as a result of its rejection by the Greek Cypriot side is the state of inconsistency and inequality that stemmed from the inability of certain international actors (the EU and the Security Council, in particular) to adopt a balanced stance between the two sides.

The main factor in the Greek side’s rejectionism was the effective manipulation in the referendum by opponents of the peace settlement of a sense that “the Greek side won’t lose anything if they say ‘no’; they can get peace on more favorable terms for themselves when they join the EU.” While the Greek side went to the polls safe in the knowledge that they would lose nothing if they rejected the Annan Plan, the Turkish side voted under the threat that ongoing embargoes might be tightened even further. The Greek side encountered no sanction whatsoever in the wake of their saying “no” but was rewarded with EU membership the following month. On the other hand, the embargo implemented against the side that had said ‘yes’ was maintained unchanged despite Annan’s report on the process, which clearly suggested lifting sanctions and restrictions against Turkish Cypriots:

The Turkish Cypriot leadership and Turkey have made clear their respect for the wish of the Turkish Cypriots to reunify in a bicommunal, bi-zonal federation. The Turkish Cypriot vote has undone any rationale for pressuring and isolating them. I would hope that the members of the [Security] Council can give a strong lead to all [Member] States to cooperate both bilaterally and in international bodies, to eliminate unnecessary restrictions and barriers that have the effect of isolating the Turkish Cypriots and impeding their development.

This privileged status has induced the Greek side to steer clear of a permanent settlement until their interests are maximized in the next rounds of negotiation. Had a balanced approach achieved a lasting solution to the Cyprus issue in 2004, the upbeat momentum of this success story would have had a positive domino effect on the search for solutions to other problems.

The third phenomenon as both cause and reflection of the aforementioned sense of insecurity and pessimism is that the emotional political atmosphere dominating today’s international environment has led to reflexive position-taking based on emotional impulses instead of a rational negotiation psychology.

This has rendered rational interest optimization impossible and caused parties to focus more on which of their supporters’ emotions can be satisfied than on what they might achieve rationally. In a sense, “interest optimization” has given way to “emotion maximization.” Escalating heroic rhetoric combined with micro-ethnic and micro-nationalist emotions have completely bypassed any negotiation psychology based on rational give and take and laid the ground for the spread of a polarizing “all or nothing” approach that raises tensions.

The fourth phenomenon is that even areas of shared values and interests impacting on the future of all humanity have been sacrificed to the confrontational language of national positions.

Continuing to take positions that are reduced to individual national interests even in matters that concern the common future of mankind, such as climate change and nuclear armament, threatens not only the international order but also the living spaces of future generations. Yet unfortunately today, the prioritization of highly individual interests even in global issues that concern all our futures is making it impossible to entrench a benevolent consciousness of international order.

It is not possible to develop an understanding of international order that embraces all humankind without a harmony and balance between the shared destiny of mankind and individual national destinies.

Implementation of the Power Structure

One of the important realpolitik principles of national and international order is the need to maintain a power structure that ensures the protection of values and the enforcement of rules.

In the event of a failure to combine internal consistency of values with the power structure in a meaningful and integral manner, there will either be no implementation area for values and rules, or it will become impossible to form a control mechanism that will keep power elements within legitimate boundaries. The former condemns the national and international order to remain on paper as an unrealized utopia; the latter makes it inevitable that all kinds of power relations will influence and transform the order in an uncontrolled manner.

Looked at from the perspective of the international order, three issues are significant in terms of power–order relations; (i) the legitimacy of uses of force designed to protect or restore order, (ii) the reflection of national power structures on international institutions, and (iii) how power–representation and power–justice balances are to be achieved in the international order.

The use of force is one of the order’s main parameters that will take shape on every plane. But the questions of how the decision to use this force is taken, the processes by which it is legitimized, and how this is reflected in the field have a decisive influence on the character of the order. Legitimacy is brought into question as the number of participants in the process that decides on using force to protect the order decreases.

For example, there was a significant difference in the legitimacy of the use of force between the processes that led up to the first (1990-1) and second (2003) Gulf Wars, be it in terms of the decisionmaking or implementation processes. In the first Gulf War, 12 resolutions were adopted by the Security Council between early August 1990 when Iraq invaded Kuwait and late November of the same year; Resolution 678 finally decided on the use of force in order to end the occupation of Kuwait and return to a legitimate state of affairs. This resolution authorized member states cooperating with the government of Kuwait to use “all necessary means” to restore international peace and security in the area unless Iraq fully implemented the previous eleven resolutions relating to the invasion and occupation of Kuwait, by a given date. In this way, the intervention to restore the pre-existing order was legitimized.

The implementation of the second intervention against Saddam Hussein in 2003 without any similar Security Council resolution(s) led to a debate on the legitimacy of the use of force that continues to this day. While the first intervention, carried out after gaining international legitimacy, achieved the ending of the occupation of a UN member-state, namely Kuwait, and the restoration of the pre-existing order, the second intervention laid the ground for developments that were to threaten the regional order as well as shake the national order in Iraq to its core.

The fact that the international institutions charged with maintaining the international order reflect the power hierarchy between nation-states to some degree may be seen as natural or even essential, as these are the only means by which measures to protect the international order can be implemented.

However, this reflection needs to be sensitive to changes in the balance of power and should not contradict the principles of representation and justice.

Looking at the power structure in the international order today, it is obvious that a serious gap has developed on these issues. With respect to the structure of the United Nations, the post-Second World War “victors’ balance” has been preserved intact in spite of the passage of three-quarters of a century, with two distinct power categories: the privileged P5 equipped with their veto power, and other countries.

The failure to reflect changes in the economic-political and military power hierarchy over this time in institutional structures has challenged the ability of emergent powers to contribute to the restructuring of the world order. In addition, while Europe is represented by three of the five permanent members of the UNSC (France, Russia, and the UK), Africa and Latin America lack any representation at all; with the exception of China, the non-Western and non-Christian cultural and civilizational basins that represent vast sections of humanity have been more or less totally ignored.

Although efforts have been made to close this gap with the G20—the platform where the world’s economic order is discussed—it offers no representation whatsoever to the least developed countries (LDCs). And while the holding of an LDC meeting parallel to the 2015 G20 Summit—hosted by Turkey in 2015, and based on the principle of inclusiveness—represents a sensitive and sensible exception, the creation of a permanent consultative mechanism like the G8/LDC or G20/LDC that oversees justice and representation, as had been planned, has remained beyond the realms of possibility.

t will be extremely difficult to form an inclusive order unless the principles of justice and representation are implemented in the power structure reflected in the international order today. This topic inevitably brings us to the principle of institutionalization.

Institutionalization

One of the indispensable principles and qualifications of any order, at any level, is institutionalization. Values find their practical manifestation through institutional structures. In the absence of institutionalization, values remain at the personal and subjective level and cannot be transformed into an order that functions through objective rules.

The most important point to note during periods in which the national and international system is on a dynamic course, institutionalization needs to be based on a dynamic process of restructuring, not a static perception of order. When the flow of history picks up speed, institutionalization’s continued reflection of the old order’s features and its adoption of a static character eventually render it anachronistic and out of tune with history. The dynamic flow of history challenges static structures and in the event that institutional resistance persists, cracks appear at first, followed by severe fissures.

The functioning of states is akin to that of the musculoskeletal system in people. In order for a person to be able to adapt to external impacts, the musculoskeletal system that gives the body form, support, resistance, stability, and movement needs to have precisely the optimum gold-standard degree of flexibility. Excessive flexibility in the musculoskeletal system (hypermobility syndrome) restricts the body’s ability sufficiently to withstand external impacts and gives rise to problems of continuity and sustainability, while a rigid, inflexible musculoskeletal system risks being suddenly fractured by external impacts.

Likewise, the survivability of institutional structures is endangered if they are overly flexible to international shocks and earthquakes, while excessively rigid institutional structures face the risk of collapse as a result of sudden fracture. The collapse of the Soviet system, which had an extremely rigid institutional structure, is a striking example of such a phenomenon. The key factor here is that institutional structures should have sufficient flexibility to facilitate the restructuring process that is required for their adaptation to new conditions.

One of the underlying causes of the earthquakes underway in the national and international system today is the fact that no restructuring process has been instigated with the capacity to adapt these structures to the dynamic course of history. The fundamental dilemma for nation-states during the Arab Spring also stemmed from this. Culturally it was anyhow difficult for harsh, exclusionary ideologies like Ba’athism (based on a Cold War rationale) to sustain themselves in an environment where revolutions in technological communications are forcing the societies of regimes that rely on tight economic-political control to open up to the outside world. The ultra-conservative struggle of these states to preserve the old order, while reform processes restructuring their institutions were needed to adapt to the flow of history, led to a considerable degree of destruction.

The international order has been prone to a similar dilemma. In spite of the earthquakes of the past quarter-century, the institutional structure of the international system has not undergone any serious process of reform and restructuring. If an evolutionarily progressive process of institutional restructuring had been undertaken starting from the geopolitical earthquake of 1991, the damage wrought by subsequent earthquakes could at least have been kept under control. However, the fact that any decisions on this restructuring process can be vetoed by the leading actors of the old order has made the system highly status quo-oriented and closed to internal change.

This leads the international institutional architecture to shake even more violently with every new earthquake. Like bones in a musculoskeletal system that have lost their flexibility, institutions that lack the flexibility to absorb shocks start to fracture. As a result, crises began to arise not from external factors but elements from within the system itself. This is why we call the widespread state of crisis in which we find ourselves a “systemic crisis/earthquake.” The institutional resistance that supported the status quo has rendered the post-Cold War crisis structural and systemic.

Institutionally, both the national and international order today perceive the need for a serious process of restructuring. Any further delay may well pave the way for an intensification of the systemic earthquake and the proliferation of destructive tensions and wars. The infrastructure for a lasting order is prepared with the presentation of a new concept of participatory, inclusive institutional architecture with a visionary perspective.

Keeping three things about this process of institutional restructuring in mind during intellectual and operational endeavors will increase the chances of success. The first is to draw the necessary lessons from past historic experiences. There are many examples of long-established imperial orders unable to adapt to and take the pulse of the dynamic currents of history being abruptly shaken. And in the modern era, it is evident from the experience of the League of Nations that weaknesses caused by inadequate institutionalization made it unable to thwart the build-up to the Second World War.

The second thing is that the new institutional architecture must reflect current balances of power—not those that prevailed in the middle of the last century—and be flexible enough to meet today’s needs. Institutionalization that fails to reflect current balances of power cannot be effective and functional in establishing order and managing crises. Likewise, an institutionalization that lacks the flexibility to include all elements in the order can hardly be all-embracing. It follows that the architecture of the new institutionalization must have the flexibility to incorporate all elements within its decisionmaking processes as well as providing a reflection of current balances of power to ensure the implementation of those decisions.

The third thing to bear in mind is that institutional restructuring must possess an intellectual infrastructure capable of anticipating potential challenges to building the order, and the operational tools to withstand them. Proactive crisis management is only possible by means of an institutional infrastructure of this kind.

One of the underlying causes behind today’s systemic earthquake is the fact that national, regional, and global institutional architecture has lost the power to withstand fresh tremors. National and international orders whose institutions have been hollowed out and rendered meaningless are like edifices made of cardboard. No matter how impressive they may appear from outside, the slightest quake leaves them in ruins.

Every step taken towards the creation of a new order requires a new institutional architecture. Instances of institutionalization that have the capacity to build sound theoretical and practical bridges between ideal values and living reality constitute the most robust buttresses for the establishment and protection of a new order. And today, efforts to establish a new order through a process of institutionalization grounded on values and made functional by living realities maintain their prospects for success.