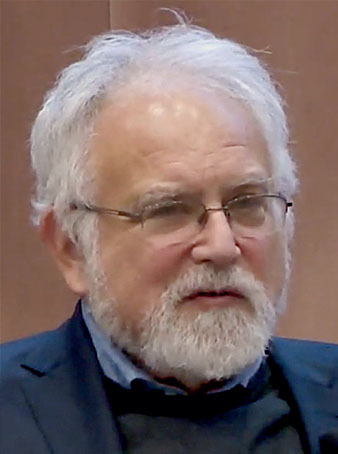

Barnett R. Rubin is Director of the Afghanistan-Pakistan Regional Project, Associate Director at the Center on International Cooperation at New York University, and Nonresident Fellow of the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft who has served as an advisor to both the U.S. Special Representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan and the Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General for Afghanistan. His next book, Afghanistan: What Everyone Needs to Know, will be published by Oxford University Press in July 2020. You may follow him on Twitter @BRRubin.

Barnett R. Rubin is Director of the Afghanistan-Pakistan Regional Project, Associate Director at the Center on International Cooperation at New York University, and Nonresident Fellow of the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft who has served as an advisor to both the U.S. Special Representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan and the Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General for Afghanistan. His next book, Afghanistan: What Everyone Needs to Know, will be published by Oxford University Press in July 2020. You may follow him on Twitter @BRRubin.

In late March 2020, after failing to broker an agreement between incumbent Afghan President Ashraf Ghani and his rival Abdullah Abdullah, both of whom claim the presidency after a disputed election, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced the State Department was slashing Afghanistan aid by $1 billion, threatening to cut another $1 billion in 2021. “This leadership failure poses a direct threat to U.S. national interests,” Pompeo charged in his statement that day.

America’s worsening economic problems will only reinforce Washington’s temptation to make more cutbacks. The impact on Afghanistan of coronavirus in the United States may rival or exceed that of the breakup of the Soviet Union at the end of 1991. In both cases, an economic crisis hit the Afghan state’s major patron at the very moment when Kabul was navigating a fragile peace process. To understand the dangers Afghanistan now faces, it’s worth remembering what happened 30 years ago.

The withdrawal of Soviet troops in 1989 was not the main reason for the collapse of the government of the ex-communist President Mohammad Najibullah in April 1992. The withdrawal of troops enabled the mujahideen resistance to consolidate its hold on the provinces and the regime’s supply lines. But it was the collapse of the foreign aid and natural gas exports that together paid for a third of the government budget that ultimately made the difference. Gas wells were capped when the Soviet troops left, and aid stopped following an agreement between the United States and the dying Soviet Union in September 1991. One third of the government’s finances, including support for food supplies, disappeared. Unpaid troops either deserted their posts or defected to the mujahideen, capturing customs posts and any other assets that could produce income. In April 1992, seven months after Soviet aid stopped flowing, Najibullah was forced to go into hiding as rival militias ravaged the capital. He was summarily executed by the Taliban when they captured Kabul in September 1996.

Avoiding a comparable outcome today requires not only planning but a degree of leadership that few in the world have shown in this crisis. Simply put, slashing aid, abandoning the peace process, or going it alone will imperil American interests in the world of 2020.

Insolvency

Today Afghanistan is even more dependent on foreign aid that it was at the end of the Soviet period. According to official statistics in 1988, 26 percent of the Afghan government budget was financed by foreign contributions and another 7 percent by sales of natural gas. Three decades on, the government’s dependence on aid has grown to more than 75 percent. Foreign aid currently amounts to nearly 20 percent of the country’s total gross national income: Afghanistan is the fourth-most aid-dependent country in the world except for five island micro-states.

Afghanistan has made progress increasing the domestic financing of its government budget—but such revenue gains are a long way from replacing the deficit financing that financed two thirds of Najibullah’s budget and to which Afghanistan no longer has recourse under its 2004 constitution. (The constitution imposes this no-overdraft rule by requiring that the central bank be independent.)

Despite massive capital flight by the private sector, the influx of foreign capital over the past two decades has left the central bank (as of the first quarter of 2020) with reserves of about $7.5 billion—equal to about 40 percent of GDP or 10 months of imports. This high level of foreign exchange reserves, however, is offset by a current account deficit (omitting official transfers) estimated at 19 percent of GDP, and years of capital flight. As long ago as 2012 the Central Bank imposed controls on the export of currency. In the third quarter of 2019, foreign direct investment declined by 88 percent from the previous year, while the outflow of net portfolio investment increased by 82 percent, strong indicators of accelerating capital flight. If foreign aid is cut, reserves would be drained rapidly, triggering collapse of the exchange rate and further acceleration of private-sector capital flight. Pressure on the government to print more money regardless of the constitutional ban on deficit spending could become irresistible, leading to dramatic rises in food prices and the collapse of the real value of Afghans’ wages.

Meanwhile, the economy of the United States—which is now Afghanistan’s principal patron—is also suffering a downturn of unforeseeable duration and dimensions. At the time of writing, almost 50 percent of the U.S. population (myself included) are currently living under lockdown orders, and that number may increase in the days ahead. Unemployment could reach 30 percent in the coming months. The U.S. economy will contract at historical levels notwithstanding trillions of dollars—amounting to more than 10 percent of GDP—earmarked for domestic relief, with more likely to come.

The amount of money needed to keep Afghanistan solvent is miniscule compared to the funds to be injected into the contracting U.S. economy. Americans who appreciate how interdependent the international social order has become must try to save as many of these expenditures as possible, but they will probably fail—even if Ghani and Abdullah manage to reach some kind of agreement on how to govern Afghanistan. Afghans and their neighbors must therefore start planning for the rapid decline of aid and other foreign capital.

The consequences could include inflation; food scarcity and shortages of other essential commodities; even higher unemployment, especially among educated youth; and a massive exodus, as thousands of Afghans attempt to flee to the Persian Gulf, Central Asia, or elsewhere. The proportion of migrants infected with the coronavirus will increase exponentially.

Prolegomena to Peace

As long as American and other NATO troops remain in Afghanistan, Afghan military and security services are likely to continue receiving foreign funding. But the opposite is also true: cuts in funding to Afghan forces will likely accelerate the withdrawal of foreign troops. The continuation of that funding will depend on both an agreement between Ghani and Abdullah and the implementation of the framework of the U.S.-Taliban peace process. Given the likely economic consequences of the pandemic in the United States, there is almost no chance the country will remain committed to Afghanistan in the long term. Progress on the presidential election and the peace process that drastically reduce security expenditures are the only alternative to collapse.

The week before signing the peace process framework agreement with the United States in late February 2020, the Taliban implemented a seven-day reduction in violence. The start of intra-Afghan negotiations on a cease-fire and a political transition within ten days of the signing was key to maintaining the reduction in bloodshed, but the Afghan government’s reluctance to release Taliban prisoners under an agreement to which it was not a party delayed the start of the intra-Afghan talks—just as the spread of the pandemic made the travel needed for diplomacy nearly impossible.

With the help of Qatar and the United States, in late March 2020—12 days after the deadline for starting intra-Afghan negotiations—technical teams from the Taliban and the Afghan government held a Skype conference call to discuss prisoner releases. On his way back from Kabul soon thereafter, Pompeo stopped in Doha, where he met Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, the Taliban’s chief negotiator and deputy leader. The two men reaffirmed their commitment to the February 2020 agreement. Pompeo announced that the Taliban were carrying out their obligations and emphasized the importance of proceeding with prisoner releases. This contrasted with his expression of disappointment in the United States’ erstwhile allies in Kabul, whom he accused of threatening American interests.

A day after Pompeo’s Doha stopover, another videoconference was held with the Taliban, with the Kabul government agreeing to start releasing Taliban prisoners by the end of March 2020.

Prisoner releases are urgent, as it is only a matter of time until the pandemic starts spreading in Afghanistan’s overcrowded detention centers, which would increase the risk of either releasing prisoners or keeping them in captivity. As a result, one day after the videoconference, the government announced it would release up to 10,000 prisoners over the next ten days. This group does not include security detainees, including Taliban. The Taliban sent a technical team to Kabul to monitor the releases but withdrew from the process in early April 2020, claiming the government was not cooperating.

Every day that passes without the release of prisoners or the start of intra-Afghan negotiations provides a chance for additional violence—such as a late March 2020 Taliban attack that killed 25 Afghan police and soldiers in a pre-dawn raid. The delays also hinder planned cooperation against the Islamic State branch in Afghanistan, which opposes the peace process. IS claimed responsibility for a late March massacre of 25 Sikh worshippers in Kabul, the last remnants of a once vital minority.

The Afghan government delayed negotiations by refusing to release prisoners and demanding a cease-fire as a condition for talks; the Taliban have delayed them by insisting on prisoner release as a pre-condition and refusing a cease-fire. The government had agreed to release prisoners but then imposed additional conditions that led the Taliban to withdraw from the process.

The Taliban should agree to a cease-fire and both sides should start intra-Afghan talks as quickly as possible in whatever format is feasible. Every day that passes without the release of prisoners or the start of intra-Afghan negotiations provides a chance for additional violence—eroding what little trust might be built among the parties.

The Afghan government is delaying negotiations by failing to release prisoners and demanding a cease-fire as a condition for talks; the Taliban delay them by refusing the much-needed cease-fire and continuing to demand prisoner release as a precondition for talks. Both sides should abandon all of these conditions, declare a cease-fire, release prisoners, and start intra-Afghan talks as quickly as possible. In such an emergency situation both sides should concede unilaterally and codify agreement afterwards. Mediation is urgently needed to facilitate this process.

Pandemic Delays

The pandemic will inevitably have a direct impact on the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan, which is the main goal of both the Taliban and U.S. President Donald Trump. The commander of U.S. and NATO forces in Afghanistan, General Austin S. Miller, has announced that new deployments as well as some departures are being delayed by quarantines and other measures. In late March (the same day as Pompeo’s Doha stopover), NATO announced that four service members recently arrived in Afghanistan had tested positive for the coronavirus and were in isolation. An additional 1,500 recent arrivals, including 38 with symptoms, were still quarantined and in isolation, respectively.

Around the same time, the Pentagon ordered a 60-day freeze on all overseas troop movements, except withdrawal from Afghanistan. Congressional clamor over the safety of the forces is mounting. Such concerns could lead to an accelerated troop withdrawal. Afghanistan’s health minister has estimated that half of Afghanistan’s population of around 32 million might be infected by the coronavirus. The likelihood that the United States will sustain military forces in a pandemic-struck Afghanistan is near zero.

A complete drawdown of American aid and military support for the Afghan government could well lead the country to collapse. But that fear should not be wasted. No one in today’s Afghanistan celebrates the fall of the Najibullah government, which led to the collapse of the state and the metastasis of war. If all sides of the current Afghan conflict understand that such an outcome is likely once more, and that there will be no return to normalcy, they might think more seriously about concessions to cease hostilities for humanitarian reasons, and work together to maintain order and minimal social services, above all public health.

Achieving such cooperation will require authoritative mediation. The day of Pompeo’s announcement, UN Secretary-General António Guterres called for an “immediate global cease-fire” to focus on “the true fight of our lives.” To implement this appeal, Guterres should appoint a personal representative for Afghanistan with a strong background in humanitarian affairs. To help that person succeed, the United States and its partners must maintain consistent aid to the Afghan state, even as they withdraw troops under their commitments in the February 2020 agreement.

Broader Cooperation?

Accepting UN or other international mediation and pivoting to global cooperation would require a massive turnaround by the United States. Washington has become accustomed to leading on Afghanistan and has elevated “great-power competition” to a strategic goal. American sanctions on Iran are hindering relief to that stricken nation, helping to spread the pandemic into neighboring Afghanistan and ultimately to U.S. military forces.

If the United States abandons the peace process, Washington’s fears of great-power competition could become real. Russia had previously started a “Moscow process,” which convened the Afghan government, the Taliban, and regional powers. If the United States cuts off aid and withdraws from Afghanistan, Russia could restart its initiative with the support of China, Pakistan, and Iran, as well as of much of the Afghan political elite.

After originally boycotting the Moscow process, however, the United States participated in a meeting in November 2018. Washington and Moscow pivoted to cooperation on the Afghan peace process after that. American and Russia broadened the process to include first China and then Pakistan. Iran declined to participate, but its inclusion is now more necessary than ever. Sanctions relief for Iran could serve humanitarian goals while also advancing strategic cooperation on Afghanistan. Iran almost immediately announced its support for the UN Secretary-General’s initiative and “declared its readiness to participate in political initiatives for the settlement of Afghanistan issues after implementation of the global ceasefire.”

This nascent process could serve as a model for broader cooperation. The United States could continue to use pressure to keep the peace process on track, while expanding its cooperation with Russia, China, and Pakistan, extending that cooperation to include Iran, and supporting the UN Secretary-General’s initiative for a humanitarian cease-fire. The same day that the Secretary-General issued the appear, the U.S. National Security Council account tweeted that “the United States hopes that all parties in Afghanistan, Syria, Iraq, Libya, Yemen, and elsewhere will heed the call of Antonio Guterres.” If so, America should urge the United Nations to convene the relevant global and regional powers. It will take urgent efforts to prevent the collapse of Afghanistan.