Adm. James Stavridis, USN (ret.), served as NATO Supreme Allied Commander from 2009–2013 and Dean of The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy from 2013–2018. He is now an operating executive of the Carlyle Group and chair of the Board of Counselors of McLarty Global Associates. You may follow him on Twitter @stavridisj. Colin Steele is an AmeriCorps alumnus and PhD candidate at The Fletcher School. You may follow him on Twitter @bravo_xray12.

Adm. James Stavridis, USN (ret.), served as NATO Supreme Allied Commander from 2009–2013 and Dean of The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy from 2013–2018. He is now an operating executive of the Carlyle Group and chair of the Board of Counselors of McLarty Global Associates. You may follow him on Twitter @stavridisj. Colin Steele is an AmeriCorps alumnus and PhD candidate at The Fletcher School. You may follow him on Twitter @bravo_xray12.

In September 1862, with his government in turmoil and parliament refusing to pass a desired military budget, King Wilhelm I of Prussia was considering abdication. After several extremely tense weeks, he was persuaded that the solution to his problems lay not in fleeing the throne, but rather in appointing a formidable new prime minister who could break the deadlock. Within a week, the parliament was told in no uncertain terms that the time for talk was over: “Germany is not looking to Prussia’s liberalism, but to its power,” Otto von Bismarck told a budget committee on the last day of the month. “Not through speeches and majority decisions will the great questions of the day be decided […] but by iron and blood.” He was known widely as “the Iron Chancellor” for the rest of his long life, and functions even today as a kind of shorthand for authoritarianism.

As we look around the world today, turmoil and apparent legislative dysfunction seem once again to be threatening democratic processes. For the better part of two decades—since the geopolitical shock of the 9/11 attacks and their aftermath, and again since the economic shock of 2008—the world’s political, economic, and social life has been described by words like complexity, flux, and turmoil. Since at least 2016, notions of global order and even norms of democratic governance have been directly called into question. This line of thinking seems to imply that the great questions of today are too knotty, too chaotic, or too fast-moving to be addressed by messy processes, parliamentary speeches, and majority decisions—validating the views of the Iron Chancellor in this twenty-first century, perhaps?

In many ways, this is the abiding and overarching question of our times: does democracy work? Democracy has never been without its detractors, and specific critiques based on messiness, slowness, or torturous progress by half-measures and unsatisfying compromises are hardly new.

Happily—at least for those of us who believe that the benefits of liberal democracy outweigh the costs—democracy has proved itself remarkably resilient throughout history. The flame kindled in ancient Athens burns on, and its light has gradually expanded to encompass many people whom those early democrats never considered enfranchising. While those lights may feel as though they are flickering today, they remain a very reasonable bet. Democracy will prevail.

Democracy’s Detractors

The charge that democracy is incapable of meeting the challenges of the present day is hardly a new one. Democracy was introduced in the United States before the Industrial Revolution, to say nothing of the communications revolution of the twentieth century or the digital revolution emerging in this century. Though the American Founders surely felt the world was moving plenty fast, information in their day moved at the speed of a horse or a ship. Today, of course, it moves at the speed of a tweet—that is, at the speed of light.

The enormous increase in the speed and volume of communications over the past two and a half centuries could reasonably be expected to have strained the always-ponderous processes of governmental decision-making to begin with. Today, our on-demand culture only adds to the challenge: when many of us take for granted the ability to buy something with one click and receive it on our doorstep within two days, it is entirely understandable that potholes that go unfilled for weeks and months are all the more frustrating. When we can purchase, read, or watch virtually anything so effortlessly, it beggars belief that jobs as basic as road maintenance can go undone for so long.

Turning our attention from municipal public works to international relations, where events are always fast-moving, complex, and consequential, the scale of the challenges only grows. After watching the bloody and chaotic aftermath of the so-called “Arab Spring,” observers can be forgiven for yearning nostalgically for the authoritarian leaders who were overthrown: at least the roads were generally built, the borders somewhat secure, and the economy functioned at a reasonable level—albeit with much graft and corruption.

It is an oft-repeated truism that nobody captains a ship by committee, after all—least of all in stormy seas. In times as turbulent as these, might it not then make sense to streamline the public administration in order to make it more responsive to citizens’ desires and the demands of the fast-changing international arena.

Democracy’s Advantages

The line of thinking sketched out above has a certain seductive power. This is true both in the abstract, as when headlines proclaim democracy in worldwide retreat; or in the petty frustrations of daily life, when it seems that no parking meter ever expires without a traffic officer waiting to dash off a ticket, while the roads themselves are perpetually poorly maintained. Especially when so much of life moves so fast, efficiency has a powerful appeal—particularly as represented in the public imagination by the private sector in general, and the high-tech sector in particular.

Before succumbing to that appeal, however, it is worth pausing to examine it in greater detail, and to ask if it is really so desirable as it might appear.

The first issue we should consider in this respect is the old tension between efficiency and effectiveness. Our culture tends to strongly prefer efficiency: we are drawn to what is fast, shiny, and new. We demand that commerce be as frictionless as possible; we insist that automakers substantially redesign their entire product lines each year.

Sometimes, however, this preference causes us to conflate efficiency with effectiveness. In that case, we not only look for what is moving fast, but also assume that anything moving fast must naturally be moving in the right direction. In real life, as anyone who has ever missed an exit on the highway knows all too well, this is frequently not the case. And, when pointed in the wrong direction, speed quickly goes from an asset to a liability. Democracy forces us to have a second look at the trade-offs, because there are competing voices at play.

A second consideration is the sheer scale and complexity of a democratic government’s work. Unlike a business, a democratic government cannot really choose to serve only a specific niche of its citizens. Instead, it has to negotiate and tack between competing visions of which policy programs will best serve all of its constituents. In practice—especially in a two-party system like that of the United States—this means that only crablike progress is achieved, with lots of scuttling sideways for any forward movement.

Think of democracy as an ungainly creature with a thousand legs that has a hard time moving in a coordinated way. Creating real cooperation is hard without direction from above. But the advantage is that many, many more interests are involved in the ultimate progress of the nation.

It is unquestionably frustrating to feel unable to walk directly towards a goal that seems to be right before our eyes. This back-and-forth is an essential part of democratic governance, however, and is rooted in an important insight about the way people function.

One of the fundamental premises of democracy is that no one person or group has or can ever have all the answers. Checks and balances are not only enshrined between the different levels and branches of government; they have also evolved between political parties such that a government may drag a country in one direction for some years, and the next will often drag it back towards the center. Slow and difficult as this method can be, it remains the best hedge yet devised against the inherent flaws of any governing party, as well as the general population’s tendency toward boredom and frustration with whomever is in power at the moment.

In this way, democracy protects both people and governments from themselves and each other, and provides important safety valves for dissent and change. For another important premise of democracy is that the great questions of government are never truly settled, but are rather in a state of perpetual negotiations.

Think of the Civil Rights movement in the United States, for example: in the first place, we could rightly say that it was a long time coming, and that it required enormous outside pressure before the government was willing to take some steps that appear downright basic today. At the same time, though, we also have to appreciate, first, that change was in fact possible and, second, that the legislative achievements of 60 years ago did not close the conversation once and for all. We need look no further than the push for equal rights for transgender individuals or the Black Lives Matter movement in our own time to see that the language and logic of civil rights are still alive and well in the land, pushing us to construct a “more perfect union” than the one we have inherited.

Democracy in Time

Beyond its accurate presumptions about the character of both citizens and government, democracy’s greatest advantage might well be its accurate reflection of government’s relationship to history. The idea of forming “a more perfect union” is planted deep in the American psyche, deposits left by our founding fathers. The same impulses came from the Enlightenment in Europe. That unusual syntax (“a more perfect union”) contains a striking insight into how governments work over historical time.

With enough hindsight, even the most progressive government will almost always be seen later as having been behind its own times. The contradictions and compromises laced through the American experience illustrate the point: the Founders certainly brought forth a new and “more perfect” form of government than the one they had been born into; but, more than two centuries later, they can rightfully be criticized for having been so badly wrong on slavery, for failing to enfranchise women, or for setting the new country on course to obliterate the native population of North America.

Bequeathing to us the dream of a “more perfect” union certainly does not absolve the framers of their mistakes, but they do deserve credit for recognizing that they would make mistakes and leaving the responsibility to correct them to future generations. Even if American history (or that of virtually any other nation) can be uncomfortable, healthy democratic governments (and their citizens) are like boats making their way along the stream of time rather than rocks planted against the current. The river of history is full of rapids, and those can make for a bumpy ride.

As a result, one of the great false hopes dangled by autocrats (and some unhealthy democrats) across time has been an offer to get off the raft and onto the rocks. Knowing people are tired of being tossed along by the current, the would-be autocrat offers easy answers and promises to restore a comfortable, numbing sense of consistency. Over time, this has failed again and again to be a sustainable system of governance.

Of course, the river of time cannot be made to flow backwards, nor can anyone build something completely impervious to erosion. No leader can restore to us life the way we remember it, which is never the way it actually was in the first place. But autocracies have a tendency to make the bold claims of Ozymandias in Percy Bysshe Shelley’s famous and deeply ironic poem:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

The king (and autocrat) and his works no doubt appeared impressive in their day; but Shelley’s poem pricks the absurd pretension that an authoritarian rule either would or could last forever. Recalling the ruined statue that bore the defiant blazon, the poem’s narrator concludes:

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

The Long Throw of History

Ultimately, democracy succeeds because it is better suited to withstand the buffeting winds of history. A healthy and functioning democracy may live long enough to pull down some of its own statues as perspectives on history change, but this itself is testament to democracy’s ability to tolerate and adapt to the changes of history. As long as the great conversation continues between competing visions of the future, and progress continues to be made (however haltingly), democracies should both eschew Ozymandias’s pretensions of immortality and escape his desolate fate.

At the moment, of course, the river of history seems to have hit an especially rough patch—one that will test democracies and autocracies alike. But we need to keep at least one eye fixed firmly on the distant horizon: just as the stock market can move dramatically from day to day and yet show unparalleled growth over the long term, democracy will endure the present stress test and emerge plenty viable on the other side. And, any time an autocrat touts the efficiencies of his system, we should critically examine its trajectory. We should also realize that the acceleration of events and transparency of action, both driven by the internet, will over time prove more of a challenge to conservative authoritarian regimes.

Democracies, for all their messiness, have a built-in flexibility that permits them to sway in the wind. Authoritarian regimes, stiff and unyielding, will eventually fall like the statues of Ozymandias.

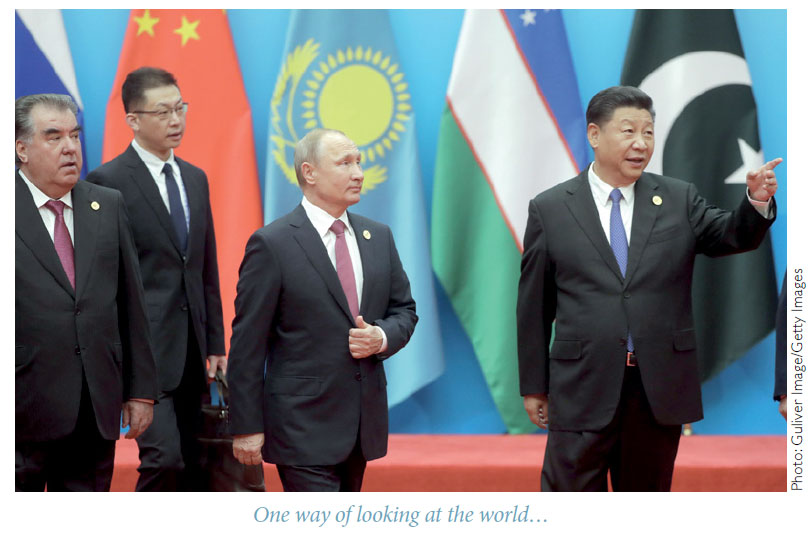

Even in difficult times, democratic countries tend to offer dramatically better quality of life than any putative competitors (even given some exceptions). Russia and China are certainly fast-moving global players, and both have made impressive gains in recent decades, but they remain woefully behind democracies large and small on the metrics that really matter.

For example, Russia and China rank 49th and 90th respectively in the UN Human Development Index (HDI), a good composite metric for national quality of life. For comparison, Norway and Australia lead the table; Canada and the United States hold ninth and tenth positions, respectively. China might have achieved more than five times the average annual HDI growth of the United States from 1990–2015, but it still has a long way to go before it can credibly offer a better all-around quality of life. Speed is impressive, but direction and destination are the metrics that really matter.

The other reason to keep an eye on the horizon of history is to keep both successes and failures in perspective. An appreciation for the long throw of history is one of the best antidotes to the natural human tendency to personalize events in both observation and experience. Much of the hand-wringing about the state of democracy in the United States either conflates the systemic flaws of our society and government with the flagrant personal flaws of our president—or skips right over the former to bemoan the latter.

By the same token, we tend to talk about the apparent dynamism of Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping as though they are accurate proxies for their countries’ own long-term fortunes. Leaving aside the question of whether it would be desirable to live under a government headed by either of those men, the really interesting question is what government will look like after them.

All governments have to account for the problem of succession, and democratic ones do so by instituting regular and frequent succession at the cost of short-term efficiency. It is a built-in safety valve of critical importance. Monarchy bets that a family line will continue to produce able leaders (and no dynasty has lasted forever), and autocracy—with its focus on the here-and-now—tends to duck the question altogether.

The more power that leaders like Putin, Xi, or the Philippines’ Rodrigo Duterte personally accrue, the murkier their succession plans become. After all, any leader holding immense personal power should be loath to give a subordinate the impression that the only thing standing between the subordinate and the levers of power is the leader himself.

If the historical problems of succession in Russia or China provide any foretaste of what may follow Putin or Xi, we should be much more afraid for those countries and their citizens than we are afraid of them.

History also strongly suggests that all people—and all leaders—have their flaws, and that a decisionmaking process tends to more closely reflect the flaws of a leader as it becomes more closely controlled by that leader. It might be impossible to run a tight ship by committee, but autocratic captains never run the happiest or most effective ships, either.

The best leaders, like the best captains, understand that the entire crew is quite literally in it together. They also understand that keeping open and honest counsel with fellow leaders does not detract from their responsibility, but rather improves the quality of their decisionmaking. By nature, autocracies tend to push decisions inward and upward rather than downward and outward, and are invariably warped by this process as the decisions become too dependent on one person’s judgment.

The Great Questions of the Day

In conclusion, let us return to Bismarck and ask whether his methods were indeed successful in addressing the great questions of his day. In our view, the answer depends on whether we limit the scope of judgment to his own lifetime. On the one hand, it would be true to say that Bismarck rapidly and almost single-handedly righted the Prussian ship of state, and indeed found an answer to the problem of German unification that had eluded generations of his predecessors. Having successfully remade the international system in Europe, he spent the rest of his time in government directing the system he had built with similar dexterity and decisiveness.

On the other hand, Bismarck’s success contained the seed of Germany’s ruin. The prospect of failure hove into view even within his own lifetime: after Wilhelm I’s death, Bismarck found himself out of favor and soon out of power, and he spent the rest of his life darkly warning that his less-competent successors’ clumsy operation of the Bismarck system would lead to calamity. Two world wars later, Germany was shattered and divided once again—and Bismarck and his balance-of-power diplomacy remain in the conversation as contributing causes of World War I. And after a long period of war and trials, the 2,000 years of Germanic history have landed firmly within the democratic camp—Chancellor Angela Merkel is clearly the value-driven democratic leader in the world, and the ideological leader of modern Europe.

The clear lesson is a common one in history: it is always worth being careful what we wish for, and never more so than in times when some purported Ozymandias comes along peddling a one-person solution to all of our problems. All forms of government involve trade-offs, and, in the long run, democracy’s preference for speeches and majority decisions is far preferable to—and far more sustainable than—the in-the-moment decisiveness of autocracy. Admitting that a “more perfect” world is always possible might mean that none of us will live to see the great questions of government settled in our own times. Yet this provides each of us with the freedom and responsibility to seek the best answers we can in our times and trust that those who follow us will do even better in theirs. The odds are strongly in favor of democracy.