Dov S. Zakheim is a Senior Advisor at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. He served as U.S. Under Secretary of Defense from 2001-2004 and Deputy Under Secretary of Defense from 1985-1987. He holds a B.A. from Columbia University and a D.Phil. from Oxford. You may follow him on Twitter @dzakheim.

Dov S. Zakheim is a Senior Advisor at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. He served as U.S. Under Secretary of Defense from 2001-2004 and Deputy Under Secretary of Defense from 1985-1987. He holds a B.A. from Columbia University and a D.Phil. from Oxford. You may follow him on Twitter @dzakheim.

On September 10th, 2019—one day before the eighteenth anniversary of the destruction of New York’s Twin Towers and the plane that crashed into the Pentagon—U.S. President Donald Trump fired John Bolton, his third National Security Advisor. The proximate reason for the firing was the disagreement between the two men over Trump’s plan to invite the Taliban leadership and Afghanistan’s head of state Ashraf Ghani to the presidential retreat known as Camp David.

The meeting was to be a symbolic reprise of Jimmy Carter’s 1977 meeting at that location with Israel’s Menachem Begin and Egypt’s Anwar Sadat, which led to the 1979 peace treaty between their respective countries. In issuing the invitation. Trump decided to one-up his negotiator, Zalmay Khalilzad, who had spent months working out an “agreement in principle” between the Taliban and the United States, which was to serve as a prelude to an agreement between the Taliban and Ghani’s government. Instead, Trump wanted to finalize the agreement himself.

Bolton had opposed the meeting, arguing that if Trump’s objective was to create an environment for withdrawing American troops after 18 years of war in Afghanistan, he did not need an agreement with the terrorist gang in order to do so. Nevertheless, despite having worked directly with the president for nearly a year and a half, he apparently still failed fully to appreciate what motivated his boss.

It would seem that, as has often been the case throughout his presidency, Trump was at least as interested in appearances as in policy. By having both sets of Afghan antagonists at Camp David—and consummating the agreement that Khalilzad had negotiated—Trump could star in a photo-opportunity such as the one depicting Carter, Begin, and Sadat; or, for that matter, Bill Clinton’s similar event on the White House South Lawn with Yitzchak Rabin and the PLO’s Yasser Arafat.

The American president then abruptly not only cancelled the meeting, but suspended any further negotiations with the Taliban, thereby undermining Khalilzad’s painstaking efforts. In so doing, however, he created the appearance that Bolton’s view ultimately had prevailed. That was a situation that Donald Trump, who often sneers at “losers,” simply could not abide. Bolton had to go. And he did.

A Unique Role

The classic role of the Assistant to the President for National Security—colloquially termed the National Security Advisor—is best exemplified by Brent Scowcroft, who held the position twice (first under Gerald Ford and then under George H.W. Bush).

Scowcroft embodied a combination of coordinator of agency positions and confidential advisor to the president. He presided over Cabinet-level policy meetings; ensured that all views were heard, discussed, and evaluated; and then presented his boss both with policy alternatives and his own preferences.

Scowcroft never sought to suppress the views of others. Indeed, because of his firm commitment to collegiality and fairness, he famously worked hand-in-glove not only with his good friend President Bush, but also with another close friend of the president’s, Secretary of State James Baker, as well as with Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney.

Some presidents have had more National Security Advisors than others. Scowcroft served George H.W. Bush during his entire term. On the other hand, Ronald Reagan had six National Security Advisors: Richard Allen, William Clark, Robert (Bud) McFarlane, John Poindexter, Frank Carlucci, and Colin Powell. While Allen, McFarlane, and Poindexter essentially were hounded out of office—not necessarily because Reagan wanted them to go—the others served their president creditably. And they supported Reagan over a period of eight years.

In contrast, Donald Trump is now working with his fourth National Security Advisor in a period of less than three years. None of the three men who served as Trump’s National Security Advisor during his first 32 months in office were cut from the same cloth as Brent Scowcroft.

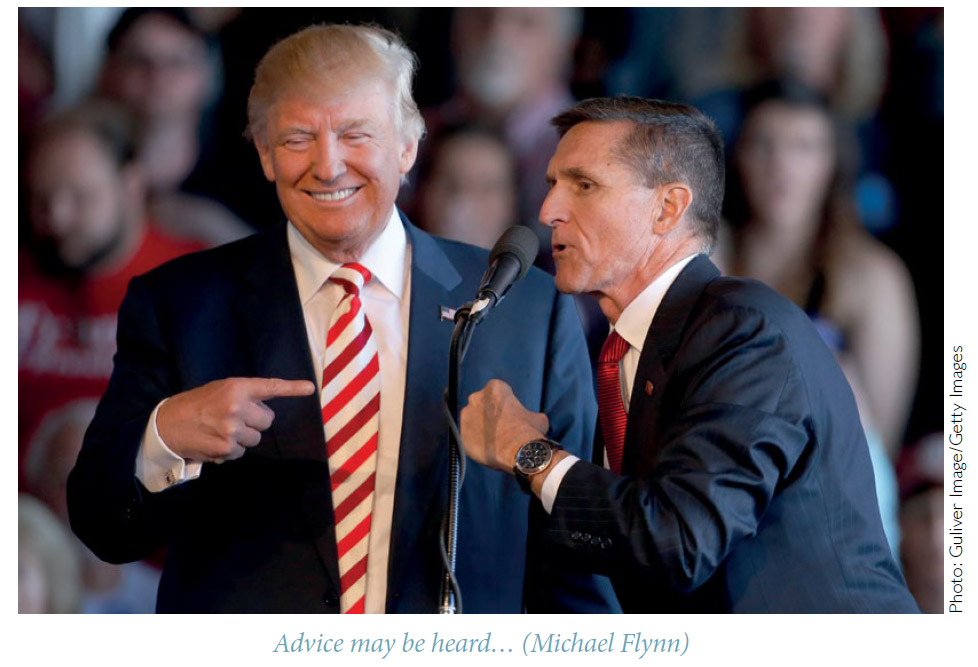

Michael Flynn

Michael Flynn, who, like Scowcroft, was a retired general, was the opposite of his self-effacing predecessor. A former head of the Defense Intelligence Agency who had been dismissed by Barack Obama, Flynn played a major role in the 2016 election, stirring up crowds by leading anti-Hillary Clinton chants of “lock her up.” He espoused unflinching support for Israel as well as exceedingly hawkish views on North Korea, China, and Iran—but, notably, not Russia.

Shortly after his election as president, Trump announced that Flynn would be his National Security Advisor. Between November 18th, 2016 (when Trump made his announcement) and January 20th, 2017 (when he took office), Flynn maintained his consulting practice, lobbying on behalf of Turkey, and accepting funds from Russia. By then he was under investigation by the Defense Department’s Inspector General, since Flynn, as a former senior intelligence official, was not permitted to lobby for a foreign power without express governmental permission.

In the meantime, however, Flynn began to construct a staff that reflected both his views and his image. Several of them had reputations that were built more on their roles as commentators on the Fox television channel than as national security professionals.

Flynn’s tenure lasted less than four weeks, the shortest tenure of any of his predecessors. Press reports surfaced regarding his financial ties to both Moscow and the Turks. It was further claimed that he had improperly made promises to the Russians after the election but while the Obama Administration remained in office, and that Obama had expressly warned Trump not to hire Flynn. When he lied to Vice President Mike Pence regarding his financial ties, he was forced to resign.

Trump reportedly continued to keep in contact with him some time after his departure from the West Wing, even as it became clear that Flynn would be prosecuted for making false statements regarding his communications with Russian Ambassador Sergei Kislyak. On December 1st, 2017 Flynn reached a plea bargain agreement with Special Counsel Robert Mueller, wherein Flynn acknowledged he had lied about his conversations with Kislyak. His sentencing has been postponed several times and has yet to be delivered as of the time of this writing.

H.R. McMaster

H.R. McMaster, Trump’s choice to succeed Flynn—after other candidates had turned the job down—hardly resembled his predecessor in personality, style, or substance. McMaster was a genuine war hero. Accounts of his victorious exploits as tank commander in the Battle of 73 Easting during the first Gulf War, often described as the most intense tank battle of all time, had become required reading for students of military history and tactics. So too was his own volume, Dereliction of Duty (1997), the published version of his doctoral thesis at the University of North Carolina. The book lambasted the military leadership for not standing up to Lyndon B. Johnson during the Vietnam War.

McMaster had long been a controversial figure within the United States Army and had once obtained promotion only through the direct intervention of then-Secretary of Defense Robert Gates. Having attained the rank of Lieutenant General, McMaster concluded that he would rise no further, and began to discuss retirement with his friends, including this writer. When Trump appointed him National Security Advisor, however, McMaster chose to remain on active duty. Technically, as a three-star general, he was outranked by some of the civilian and military personnel that were the principal participants in the Situation Room meetings that he chaired. Military protocol later proved to be an element in his undoing.

McMaster brought some coherence to the national security process, as well as to the management of the National Security Advisor’s staff in the wake of the chaos that resulted from Flynn’s sudden departure. He dismissed many of Flynn’s appointees, including his deputy K.T. McFarland, replacing her with Dina Powell, who had been widely respected while serving in George W. Bush’s White House. He continued the traditional practice of maintaining an inter-agency process, chairing Cabinet-level meetings and assigning his deputies to chair meetings of sub-Cabinet officials.

Most important, observers and analysts viewed McMaster as an “adult.” They asserted that together with Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis and Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, McMaster was a restraining influence on the president. No less important, McMaster, together with his deputy Nadia Schadlow, authored the Trump Administration’s National Security Policy report that assigned greater priority to coping with a rising China, as well as an aggressive Russia, than to the war on terror or, for that matter, the Middle East.

Nevertheless, McMaster soon found himself increasingly isolated. He had considerable difficulty relating to Mattis, who as a retired four-star general outranked him, and whom McMaster reportedly perceived was not treating him with the respect he was due. For his part, Mattis was uncomfortable with McMaster’s temper, which flared up far too often for the Secretary’s taste. McMaster’s relationship with Trump’s then Chief of Staff John Kelly—like Mattis, a retired Marine four-star general—likewise deteriorated. In the meantime, Tillerson, the third leading member of the national security triumvirate, was himself falling out of favor with Trump, leaving McMaster in a precarious position vis-à-vis a president whose preference increasingly was to rely on his own instincts rather than on the advice of staff.

McMaster also had been under attack from hardline conservatives, including the president’s erstwhile political guru, the ultra-nationalist Steve Bannon, virtually from the day he took office. They viewed him as excessively soft regarding Iran, North Korea, and Islamic terrorists, not to mention being hostile toward Israel, all of which they asserted were policies more closely associated with Barack Obama than with Donald Trump. Moreover, the nationalists bitterly resented McMaster’s firing several Flynn’s key staffers, who more closely reflected their own ideological predilections.

It quickly became apparent that McMaster’s policy disagreements were as much with the president as with the far-right or colleagues in government—and certainly of far greater consequence. In particular, he and Trump were not on the same page regarding the president’s hard line on Iran. McMaster argued that Tehran was complying with the terms of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), colloquially known as the Iran nuclear arms deal, while Trump clearly was itching to walk away from an agreement that he had bitterly criticized during the 2016 election campaign and that the Obama Administration had claimed as one of its crowning achievements. McMaster was also openly more hostile toward Russia, whereas the president appeared to make every effort to cozy up to Russia’s President Vladimir Putin.

McMaster’s style, akin to that of a military briefer, did not fit well with the president’s notoriously short attention span and his widely reported indifference to detail. Trump reportedly would tune out the man who was supposed to be his top advisor on national security matters. McMaster’s days were therefore numbered and rumors of his imminent dismissal surfaced early in March 2017. Trump dismissed him later that month; McMaster had served in his position less than fourteen months.

John Bolton

Having rejected McMaster, a man who looked and sounded the image of the tough military man that he was, Trump turned to someone very different. The president had passed over John Bolton after Flynn had imploded, supposedly because he could not stomach Bolton’s walrus mustache. On the other hand, Bolton’s aggressive style and instincts, which were on constant display on the Fox News channel, seemed at the time to be very much in line with the president’s views, and the mustache no longer stood in the way of Bolton’s appointment.

Bolton was a long-time skeptic regarding both international agreements and institutions of all kinds. In this regard his views meshed with those of the president, who constantly disparaged the European Union and had little time for NATO and for the majority of its members who failed to contribute what he felt should be their “fair share” toward the common defense. Bolton was a long-standing supporter of Israel and of a hard line toward both the Palestinians and Iran, to the degree that the Israelis considered him their best friend in government apart from the president himself.

Bolton replaced McMaster’s team with his own acolytes, all of whom reflected his own aggressive, virtually warlike stance vis-à-vis Tehran, Pyongyang, and Moscow. He found a kindred spirit in Mike Pompeo, the Director of the Central Intelligence Agency, who replaced the hapless Tillerson as Secretary of State within weeks of his own appointment. Pompeo, had finished first in his class at West Point, and after a stint in the Army and a successful if short business career, had been elected to the House of Representatives as a member from Kansas, a state that overwhelmingly supported Trump in the 2016 election. Pompeo shared Bolton’s distrust of Iran, as well as his unswerving support for Israel. But having served under Trump for two years, Pompeo had got the measure of the man, and, unlike Bolton, was both able to trim his ideological sails to suit the president’s fluctuating policy positions, and, perhaps as a result, influence the president in a manner that Trump did not find to be threatening.

Bolton simply could not match Pompeo’s subtlety. Moreover, unlike his predecessors, of whatever political persuasion, he did not even attempt to coordinate the inter-agency process in any sort of coherent fashion. Meetings of principals were few and far-between; Bolton increasingly sought to centralize decisionmaking in his office.

Not surprisingly, Bolton clashed with Secretary of Defense Mattis, who not only had a much less ideological approach to national security, but also had a marked preference for a more structured national security process. With time, however, he also found himself at odds with Pompeo as well. Bolton had never been able to shed his reputation from his days in the George W. Bush Administration as a man who did not work well with others, and his behavior as national security advisor indicated that he had not undergone a character change. However, it was Mattis who left the Trump Administration, not Bolton. The Secretary of Defense had differed sharply with the president’s constant belittling of America’s allies, and, when Trump announced the withdrawal of all American troops from Syria (a decision he later rescinded), Mattis had enough and resigned.

Bolton’s position appeared to be secure. He and Pompeo appeared to have congruent policy preferences. As for the Defense Department, it was now being led on an “acting” basis by Patrick Shanahan, Mattis’ former Deputy, whose open desire for formal nomination to the top job led him to take a back seat to the other two national security principals.

It was inevitable, however, that Bolton and his team would at some point fall out of favor with President Trump. In contrast to Bolton, whose bedrock commitment to long-held principles underpinned his approach to national security issues, the president was not in the least ideological. Instead, what drove him was an all-encompassing concern for his image and his prospects for re-election. He therefore could veer from the hardline Flynn to the more balanced McMaster and then back to the hard line that Bolton espoused. The only question therefore was how long it would take before the president altered his views once more, and thus ultimately precipitate a complete break between the two men.

There can be little doubt that even as he took the job, Bolton was fully aware that there was something peculiar about his new boss’ relationship with Vladimir Putin. Trump had held a private hour-long meeting with Putin on the fringes of the July 2017 G-20 meetings that was so private that Trump allowed no note takers to be present. Moreover, Trump would continually downplay any effort to demonize his Russian counterpart. That Trump had sought for nearly two decades to obtain Putin’s support for the construction of Trump hotels in Russia contributed to widespread suspicion about just what passed between them. Bolton also was aware that it was in part because of their clearly diverging views of Putin that Trump had fired McMaster.

Despite these concerns, Bolton was prepared to work for Trump. Perhaps he convinced himself that either he could alter the president’s views of Russia, or simply work around them. Similarly, Bolton appears to have explained away, at least to himself, the president’s March 2018 decision to meet with the North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un. Kim, like his father before him had always sought to meet with the incumbent American president, in order both to sidestep the South Koreans and Japanese, and to establish North Korea’s position as a viable interlocutor with the American superpower. It was for precisely those reasons that all of Trump’s predecessors had refused to grant Kim, père et fils, that privilege.

Bolton had always advocated the hardest possible line against Pyongyang. He had argued that sanctions had failed to halt Pyongyang’s march toward a nuclear capability, and advocated attacking the North so as to defang it once and for all. Thus, when only weeks before he replaced McMaster with Bolton, the president announced his intention to meet with Kim, Bolton supported the meeting on the ground that it would demonstrate that Kim was a liar and a fraud.

It soon became clear, however, that despite Trump’s seeming belligerence—at one point insulting Kim by calling him “little rocket man”—the president genuinely intended to reach an understanding with the North Korean leader. When he and Kim met in Singapore in June 2018, Bolton was forced to swallow hard as the two men issued a joint statement that seemed to allow the North Korean considerable wiggle-room regarding the North’s dismantling of its nuclear weapons capability.

One month later, another cloud appeared on Bolton’s horizon when Trump met with Putin in Helsinki. To the amazement of virtually everyone, Trump rejected the unanimous view of his own intelligence community and accepted Putin’s assertion that Russia had not interfered in the 2016 presidential election. Once again, Bolton kept his own counsel, seemingly valuing his job over his long-held hardline attitudes.

Then came the Venezuelan crisis, which has yet to be resolved. Bolton had openly advocated the overthrow of Venezuelan strongman Nicolas Maduro. Trump appeared be on the same page, having stated as early as August 2017 that he would not rule out military intervention against Maduro’s government. But Bolton was far more vociferous than the president about dethroning Maduro and replacing him with Juan Guaido, leader of the Venezuelan Congress.

For a time it seemed as if Guaido would successfully overthrow Maduro, with Bolton urging military intervention to support the Congressional leader. But an attempted “revolution” fizzled, and Bolton’s advocacy notwithstanding, Trump appeared to have lost interest in Venezuela’s political chaos.

Finally there was the question of Trump’s dealings with Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky. Bolton evidently was unaware of the contents of Trump’s conversation with the Ukrainian leader, which subsequently led the Democratic Party controlled U.S. House of Representatives to launch an impeachment enquiry. To the extent that Bolton knew what was happening, he could not have been very happy about it, as it appeared that for reasons not yet revealed, the White House was holding up aid to Ukraine, contrary to Bolton’s own preferences.

In the event, the break between Trump and Bolton came after just over sixteen months, two months longer than McMaster’s tenure. Having been side-stepped on Russia (and, apparently, Ukraine as well), ignored on Venezuela, and overruled on the future of relations with both North Korea and Iran, by September 2019 Bolton’s days clearly were numbered. His inability to work with colleagues, even those like Pompeo who generally shared his hardline views, and his temerity in debating policy with a president who abhorred pushback from his staff, finally led to Bolton’s departure.

Trump opined that he missed McMaster, and indeed, had told the retired general as much around the time that Bolton was on his way out. In the event, just over a week later, the president named Robert O’Brien as his fourth National Security Advisor. O’Brien had been serving as Special Envoy for Hostage Affairs; during the George W. Bush Administration he had served alongside Bolton on the American delegation to the United Nations.

Robert O’Brien

O’Brien is no Bolton, however. Unlike his immediate predecessor, O’Brien appears to have the ability to work amicably with conservatives of all stripes. For example, he supported Governor (now Senator) Mitt Romney’s 2012 presidential campaign. Though Romney is a far more Republican establishment figure than Bolton, both men contributed blurbs for O’Brien’s most recent book on national security issues (it was his third), entitled (as per John Kennedy’s volume on pre-World War II Britain) While America Slept: Restoring American Leadership to a World in Crisis (2016). So too did former Senator Jim Tallent, another establishment figure, and Richard Grenell, currently Ambassador to Germany, who is cut from the same cloth as Bolton.

It is also noteworthy that in his volume O’Brien not only argued for a strong American defense posture, but in so doing invoked the spirit of Ronald Reagan, that “it is time to return to a national security policy based on ‘peace through strength.’” And, he added, rather like McMaster and Mattis, “a strong America will be a nation that our allies will trust and our adversaries will not dare test.’

O’Brien, a senior partner in a successful law firm, appears to have the lawyerly knack of keeping his clients happy. As the State Department’s chief negotiator for the release of hostages, he nurtured Trump’s seemingly insatiable desire for the limelight. Accordingly, although O’Brien led negotiations for the release of a number of hostages, including three Americans hostages held by North Korea, as well as the body of Otto Warbier, who had died after being tortured by his North Korean captors, he seems to have been content to have Trump receive all the credit.

Prognosis

Trump’s choice of O’Brien appears to indicate that the president remains determined to avoid the sorts of military adventures that Bolton advocated. Nor does Trump wish to engage in overly aggressive posturing against putative adversaries, unless circumstances dictate that he has no other alternative.

The Iranian attack on Saudi oil facilities provides a case in point. Trump initially rattled his rhetorical sabre against the Tehran regime. Ultimately, however, he appears to have chosen to forego a kinetic military response, instead imposing more sanctions and possibly also employing other non-kinetic means to punish Tehran. That approach, which McMaster but not Bolton might have advocated, is one that, if his record is any indication, O’Brien could easily support.

O’Brien is likely to resurrect the more orderly national security process that withered away under Bolton’s leadership. His background as a veteran international arbitrator points to an ability to listen to all sides before making a decision, which should serve him well in his new position.

How long O’Brien will remain in Trump’s favor is, of course, an open question. Trump’s mercurial approach to national security policy, coupled with his at times demeaning treatment of senior staff, is sure to test the patience of even the most accommodating individual. But O’Brien’s background points to a more positive prognosis about his fortunes than Bolton ever had. Like Pompeo, it appears that O’Brien will be able to advise his boss in a non-threatening manner. In effect, he is much closer to the Scowcroft model of a successful national security advisor than any of his three predecessors. He thereby not only will support Trump as the only star of his own political show, but also ensure that his own tenure as National Security Advisor will extend to the final days of Trump’s current term of office, and, if Trump is re-elected in 2020, well into the next one.