Stephen M. Walt is the Robert and Renée Belfer Professor of International Affairs at Harvard University and a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. You may follow him on Twitter @stephenWalt.

Stephen M. Walt is the Robert and Renée Belfer Professor of International Affairs at Harvard University and a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. You may follow him on Twitter @stephenWalt.

Having won the Cold War and achieved a position of primacy unseen since the Roman Empire, why did America’s leaders decide to maintain a military establishment that dwarfed all others and expand an already far-flung network of allies, client states, military bases, and security commitments? Instead of greeting the defeat of its principal rival as an opportunity to reduce America’s global burdens, why did both Democrats and Republicans embark on an ill-considered campaign to spread democracy, markets, and other liberal values around the world?

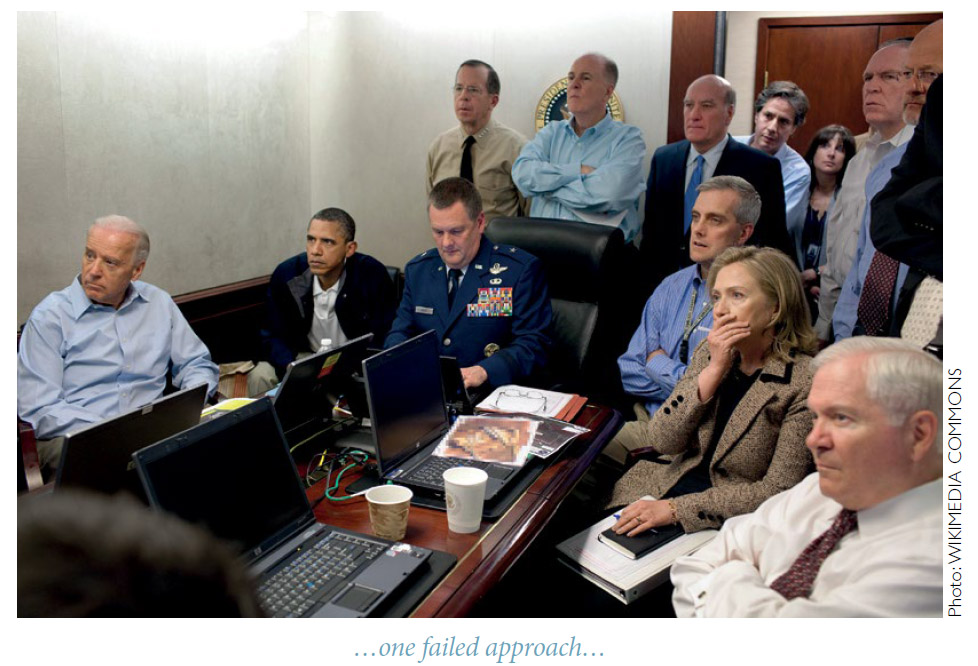

This strategy—sometimes termed “liberal hegemony”—has been a costly failure. Yet three successive American administrations—under Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama—clung to it, even as the costs mounted and the quagmires multiplied. Why did Washington persist in the face of repeated setbacks, and how did the foreign policy establishment convince the American people to support policies that were neither necessary nor successful?

Part of the explanation is America’s remarkable combination of wealth, power, and favorable geography. Because the United States is the world’s most powerful nation, faces no threats in the Western Hemisphere, and is protected from the rest of the world by two enormous oceans, it can intervene in distant lands without placing its immediate survival in jeopardy. Yet this explanation is not the whole story, because those same favorable circumstances would also permit the United States to reduce many of its overseas commitments and focus more attention on problems at home.

Instead of pursuing a more restrained grand strategy, American leaders opted for liberal hegemony because the foreign policy community believes spreading liberal values is both essential for the security of the United States and easy to do. They convinced ordinary citizens to support this ambitious agenda by exaggerating international dangers, overstating the benefits that liberal hegemony would produce, and concealing the true costs. And because members of the country’s foreign policy elite are rarely held to account, they were able to make the same mistakes again and again.

The American foreign policy establishment deserves much criticism, but the nature of my critique needs to be properly understood. America’s foreign policy elite is not a conspiracy of privileged insiders who are consciously seeking to advance their own fortunes at the nation’s expense. On the contrary, America’s foreign policymaking institutions are filled with dedicated public servants who genuinely believe that American dominance is good for the United States and for the rest of the world. At the same time, however, the pursuit of liberal hegemony appeals to this elite’s sense of self-worth, enhances their power and status, and gives them plenty to do. These individuals also operate in a system that rewards conformity, penalizes dissent, and encourages its members to remain within the prevailing consensus.

In short, most of the men and women who play a role in formulating and executing U.S. foreign policy have tried to advance the national interest as they saw it. Unfortunately, the strategy they pursued with such energy and dedication was fundamentally flawed, and their mistakes were sometimes egregious.

And now we come to Donald Trump.

Being President is Hard WorkDonald Trump’s unexpected victory in November 2016 was an awkward surprise in more ways than one. Both as a candidate and chief executive, Trump had challenged, albeit haphazardly, many enduring orthodoxies about U.S. foreign policy, and he was openly dismissive of (and dismissed by) Democratic and Republican foreign policy experts alike.