Franco Frattini is President of the Italian Association for the United Nations (SIOI–UNA), having previously served as Italian Foreign Minister and Vice-President of the European Commission. You may follow him on Twitter @FrancoFrattini.

Franco Frattini is President of the Italian Association for the United Nations (SIOI–UNA), having previously served as Italian Foreign Minister and Vice-President of the European Commission. You may follow him on Twitter @FrancoFrattini.

The main objective of the 1995 Barcelona Process was to transform the Euro-Mediterranean region into a common area of peace, stability, and prosperity encompassing the two shores of the Mediterranean. However, more than two decades later—and despite some positive improvements in terms of local reforms—we must admit that the objective of building a sphere of shared security and prosperity is still far from being achieved.

In recent years, the Mediterranean has moved from the periphery to the center of global security concerns. The deteriorating conditions in Iraq, Syria, and Libya confirm that the overall situation has become even worse in the wake of the Arab Spring.

Today, the region is a patchwork of unresolved geopolitical problems: from the Israeli-Palestinian conflict to the ongoing crises in Libya and Syria. Such factors are further damaging political, economic, and social development efforts in Southern Mediterranean countries. Moreover, the escalation of terrorism and irregular migration flows confirm that a large gap still exists between Western countries’ strategies and the needs of their Mediterranean partners—especially in terms of security and future opportunities for younger generations.

These two factors are not entirely disconnected, since the main problem at hand is that young people are becoming increasingly frustrated with the lack of job opportunities in their respective countries. Killing terrorists will not solve the ‘root problem’ that causes people to join terrorist organizations like Daesh.

To deal with this issue in a meaningful way and resolve it in the long run, local economic environments need to become more dynamic and able to offer more youth employment opportunities. Most young people in urban and rural areas hold a real desire to find jobs, advance their lives, and be of use to their families and communities. Otherwise, the permanent lack of gainful employment will compel too many of them to risk their lives in order to improve their status—either by trying to cross the sea or becoming involved with terrorist and criminal groups.

The arc of crisis in the region is even longer if we take into consideration the vulnerability of some specific countries, like the strip of land running from western Africa through the Sahel and the Horn of Africa, up to the Gulf of Aden and the Arabian Peninsula. Taking action in the context of the Mediterranean means strengthening a region that forms the crossroads of three continents: Europe, Africa, and Asia. If the Mediterranean breaks down, the global architecture of international relations will be compromised, with longlasting consequences—not just in the region itself, but for the West and the EU as well.

The many crises across the Mediterranean region pose difficult and unprecedented challenges to our European agendas and identity. They call into question our ability to act together and defend what we are, as well as our ability to affirm the right of others to a peaceful and prosperous life, free from fear and want.

The Mediterranean is vital to Europe’s own peace, stability, and economic growth. Our neighbors to the south and east look to Europe as a natural partner, because of geographical proximity and because these countries have always ranked highly in our external relations. That is the reason why the recent crisis is stressing, more than ever, the need for a stronger and more comprehensive cooperation policy that embraces the whole region.

European Response

In recent years, the European Commission has set out plans for a new results-oriented partnership framework that mobilizes and focuses EU action and resources in our external work on managing migration—the most urgent threat facing the poor in developing countries. The EU has sought tailor-made partnerships with key countries of origin and transit, using Brussels-based policies and instruments to achieve certain results. These include saving lives at sea, increasing the number of returns, enabling migrants and refugees to stay closer to home, and, in the long term, helping third countries’ development in order to address the root causes of irregular migration.

But these measures have not always attained their goals, in part because EU Member States always appear to be divided and unable to agree on common solutions.

What is happening at the borders of Europe is both a mirror of the political complexity of these societies and a manifestation of the failure of our attempts to save the Mediterranean after the Arab Spring revolutions.

Events in the Southern Mediterranean since the onset of the Arab Spring in 2010 have provided a unique opportunity for citizens in these countries to express a desire for democracy, human rights, and fundamental freedoms. Yet this “spring” quickly turned into a “summer of discontent,” characterized by violent revolutions, and, in some cases, civil war.

In a few short years, Egypt experienced its first democratic elections, the brief presidential tenure of Mohammed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood, another wave of protests over his misrule, a military coup, and, finally, a presidency under former army chief Abdel Fattah al-Sisi. Meanwhile, Syria descended into civil war, with parts of its territory still in the hands of Daesh. Yemen and Libya remain essentially failed states. Only Tunisia can claim to have successfully navigated the transition to a democratic government.

Frankly speaking, I have not seen Europe play a strong role in the Arab Spring. Reasons for this include the Old Continent’s own political divisions over Syria, the fact that the West left Libya to its own devices after the overthrow and death of Muammar Gaddafi, and Europe’s economic struggles. This failure also had as a consequence the onset of historically high migration movements—mainly from Southern Mediterranean countries towards their immediate neighbors, as well as towards the EU.

Chaos, a resurgence of terrorism, the rise of radical Islamism, the Daesh dilemma, and the massive flows of immigration towards Europe are just some of the threats to the EU’s vital economic interests that are now being identified. It is against this backdrop that we should take action to prevent the complete deterioration of the security environment. I stress the concept again: Europe’s primary aim for a new “Mediterranean Compact” must be to support growth and stability in the region as a whole.

A New Marshall Plan

he Marshall Plan at the end of World War II consisted of a financial aid package aimed at reconstructing and re-launching Western European economies in a bid to bolster their political stability. A similar aid program is essential for the Mediterranean region, which has been facing challenges over the past six years comparable to its 1948 western European counterparts.

Italy tried to accomplish such a program during my tenure as Foreign Minister, from 2008 to 2011. At the time, I stressed the importance of such a task to my European colleagues and asked for their help in shaping a new order in the Mediterranean region. Throughout this period, I made one principle very clear: democratic transitions in the Mediterranean have to be determined, of course, by each country; but Europe, acting respectfully, can and should help with instituting a new order through an ambitious development and stability pact based on three pillars: substantial (and visible) economic assistance; political partnership; and social inclusion.

The idea was very simple and suitable for the Mediterranean region. The first step—a goal that has yet to be achieved, regretfully—was to promote growth by improving the European Union’s neighborhood policy. We did, in fact, increase the availability of some resources for programs that stimulated growth and job creation, though it was not enough.

It is true that poverty has not been eradicated in the Mediterranean, despite having been significantly reduced in several countries. The institutional economic framework in the region remains deficient, except in a few countries that have experienced some progress. Human development is still low, while foreign investment remains well below international standards.

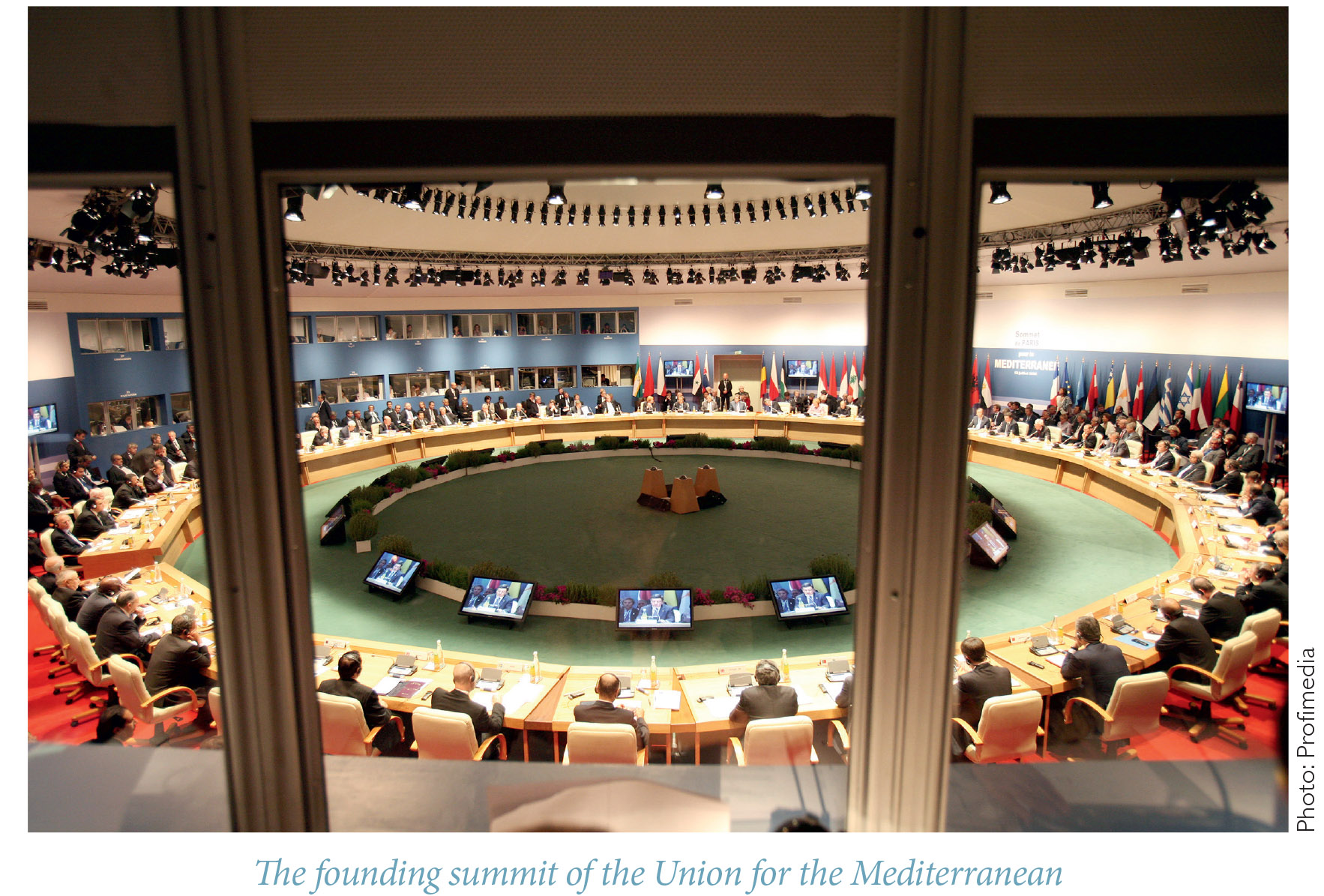

The Union for the Mediterranean (UfM), created in 2008, could accelerate the implementation of these projects. Despite this, too much time has been lost in setting up the institutions of this organization—a 44-member body incorporating the EU Member States and 16 Balkan, North African, and Middle Eastern partners. Without a doubt, the results of the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership have remained a dead letter in many domains—empty and unfulfilled promises that stand as a testament to the gap that exists between European rhetoric and European action.

Since UfM’s founding, it has become quite obvious that civil society activities can only develop broad and positive dynamics when accompanied by changes in the larger political framework, as has been the case in, for example, Morocco. There is no easy way out of these predicaments. In the long term, the only solution remains political reform.

A broader economic initiative is also sorely needed. I stressed this point to my then-colleagues many times. For example, in 2010, when I launched the Marshall Plan for the Mediterranean, I said:

The EU, other world powers, and international institutions, such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, should urgently develop an equivalent of the Marshall Plan for Mediterranean economic stability.

And again:

This plan must mobilize a critical mass of new European and international financial resources—in the order of billions of euros—to modernize the economies of the region and improve investment. The removal of trade and economic barriers between Mediterranean countries should also be a priority. The EU should work together on this strategy with the United States, whose role remains crucial in this region.

But I also emphasized some conditions: “My proposed development and stability pact would include a commitment from each country to improve governance, meet international obligations, and respect individual rights—including for women and religious minorities. Change in the Mediterranean is a test for Europe. But it is also an opportunity for European and Mediterranean countries to work together in the interests of all.” That’s what I said then, and I stand by it now.

The approach was appropriate, and the proposal to create a Euro-Mediterranean Investment Bank to help fund the transition to democracy in countries on the Mediterranean’s southern shore gained momentum at the March 2011 Union for the Mediterranean Plenary Assembly in Rome. As stated by the official press release at the conclusion of that meeting:

A new Marshall Plan should enable us to improve economic relations and development, but also improve security in the region. We cannot open a channel for a huge influx of desperate persons coming to Europe. We call for a new plan for the European Investment Bank to invest in the region, as was done by the EU to improve stability in the Western Balkans back in the 1990s.

This was the view that I put forth on behalf of Italy while it held the UfM’s rotating Presidency. The declaration was broadly welcomed and adopted. Unfortunately, that was the period in which the global economic crisis worsened, and it was generating suffering for European countries as well. As a consequence, European institutions remained too narrowly focused on the financial issue, slowly forgetting what was needed more broadly.

We grew to believe that conventional war was the only form of war. But the paralysis of all of the initiatives taken in the past for the Mediterranean relaunch has shown us that this belief was an illusion. The world has not changed for the better: we live in a less secure world than we did five years ago. Moreover, running away from the Mediterranean—disengaging on important issues—has not made things easier.

The Middle East has exploded. Muslims are often the first victims of terrorists and fanatics. The rise of Daesh, a terrorist group calling itself a state, is a reality of our era. It is a criminal organization with more resources, manpower, and ambitions than any other terrorist group in history. Europeans can no longer afford to disregard what happens to ‘faraway’ people.

The evidence of this can be seen in Europe’s worsened security situation. The sequence of terror attacks over the recent past has spared no symbol of Europe: from Madrid’s railway station, the London tube, and the subway and airport of Brussels, to the Paris office of Charlie Hebdo, the Bataclan attack, and the terror in Nice.

It is not enough to build walls to defend ourselves against these atrocities. Today, “Je suis Charlie,” “Je suis Paris,” “Je suis Dacca,” are refrains that also require the courage to act with strategy and unity to defend our values. We cannot stand by passively. No Member State of the European Union can consider itself a mere spectator of the tragedies that are playing out on the Mediterranean stage. At the same time, there is no country in Europe that is able to address these serious crises on its own. The only solution is for the whole of Europe to make a decisive contribution to their resolution.

The Refugee Crisis

In all honesty, however, in order to be successful, we need to make a U-turn of sorts, a change from what Europe has done so far—or refused to do. The record of European action in the Mediterranean is marked by failure, with the refugee crisis standing as the most vivid example of this.

Pushed by civil war and terror, and drawn by the promise of a better life, huge numbers of people have fled the Middle East and Africa, often at great personal risk. More than a million migrants and refugees crossed into Europe in 2015, as opposed to just 280,000 in 2014. The scale of the crisis continues, with more than 140,000 people arriving in the first six months of 2016.

This wave of migration is presenting European leaders and policymakers with their greatest challenge since the debt crisis. The International Organization for Migration has called Europe “the most dangerous destination for irregular migration in the world,” and has labeled the Mediterranean as “the world’s most dangerous border crossing.”

Yet, despite the escalating human toll, the European Union’s collective response to this current migrant influx has been ad hoc: it has never focused on the issue with a real, common, unanimous position. In the recent past, northern Europe believed that it was sheltered from modern geopolitical threats that predominantly came from the southern half of the EU. Likewise, following the Russo-Ukrainian crisis, Central European countries believed Moscow was the only possible threat to its security. But as facts have shown, these were just misconceptions.

Migration fluxes and Daesh’s terrorism are global issues that concern the whole of Europe. They must be tackled collectively, and everyone must contribute to a solution. To ignore such a demand, and to keep Europe divided into north, east, and south in a process of endless bargaining, is a political and historical mistake. Such self-representation weakens our standing in the world.

igration is a dramatic issue, but we should not call it an emergency; rather, it is a long term challenge. Many countries, far from the shores of the Mediterranean, mistakenly believed they would remain safe by ignoring what was going on just a few kilometers away from Southern Europe’s borders. The sad truth is that the majority of European leaders only started to take action when the tragedy began to hit home as a result of the refugee threat; or when hundreds of men, women, and children drowned off the coast of Lampedusa island; or when the picture of a dead child lying on a Turkish shore was published on the front pages of prominent publications. It was only when confronted by these situations that many Europeans realized the scale of the problem.

The issue of migration flows has been on the agendas of Euro-Mediterranean policymakers for a long time, and with good reasons, given its importance: the Mediterranean Sea has been called the “barometer of world politics” in places as far apart as New York, London, Geneva, Brussels, Moscow, and Tehran. Three continents meet on the Mediterranean basin: Africa, Asia, and Europe. Diverse political systems, socio-economic conditions, three great monotheistic religions, and three continents share this common space, which makes it one of the world’s most interesting and tense areas.

But what is the reality? Words of solidarity consistently follow the tragedies that occur; but most of the time, Italy and its fellow south European neighbors have been left alone to cope with the influx of hundreds of thousands of desperate asylum seekers.

The farther European countries are from the Mediterranean, the more they demand the strict implementation of the Dublin regulation—an obsolete system of rules that requires the first country of entry to deal with asylum applications by itself.

In June 2016, the European Commission announced a new Migration Partnership Framework to reinforce cooperation with external countries and better manage the migrations. Here is what was said, in part:

The EU will seek tailor made partnerships with key third countries of origin and transit using all policies and instruments at the EU’s disposal to achieve concrete results. Building on the European Agenda on Migration, the priorities are saving lives at sea, increasing returns, enabling migrants and refugees to stay closer to home and, in the long term, helping third countries’ development in order to address root causes of irregular migration. Member State contributions in these partnerships-diplomatic, technical and financial-will be of fundamental importance in delivering results.

This is good news, and perhaps, for the first time in the past five years, this declaration acknowledges serious political awareness on the issue of migration in the EU’s institutions. But this is hardly enough. Europe has to strengthen partnerships with nations in which modern challenges originate, instead of leaving them to their destiny. This is simply because if the Mediterranean region explodes, the EU as a whole will explode too.

Leadership Needed

A comprehensive Mediterranean compact is badly needed, where all global and regional players sit at the same table alongside international financial institutions.

This means that political leadership is a necessary precondition, because the present reality is devoid of comprehensive vision and leadership linking internal and external security to global challenges. We need to invent a new global governance. Let us remember that we are talking about human beings, not numbers or pieces of paper. This is the key leading value that should guide us.

The current crises in Libya, Syria, and Iraq will not be fixed immediately. For this reason, we must act rapidly to set the foundation for a future solution. We have the political responsibility and the moral duty to draft a long term comprehensive strategy that will contribute to the stabilization of the entire Mediterranean—a region increasingly exposed to the threat of jihadist organizations.

Establishing security in the Mediterranean has always been a great challenge. But let me emphasize again that there is no real security if we do not encourage socio-economic development. Only a stable environment—with the rule of law enforced by a functioning state, the respect of human rights and the rights of minorities, job prospects for youth, a culture of inclusiveness, and the promotion of the role of women—can be the real gateway to stability and peace in the Mediterranean.

We are going through a kind of asymmetric world disorder, where humanity is simultaneously the founder, perpetrator, and victim of today’s global chaos. Such a vicious cycle has to be broken. Hundreds of millions of people live in desperate poverty and frustration, while global powers continue to pollute the environment, thereby aggravating their social condition. For instance, are global powers talking about access to water, which in some regions can easily become the inciting factor for war? Not enough—if at all.

What we do see is the absence of EU institutions on the international scene, America’s disengagement from the wider Middle East (with a few exceptions), and the role of the BRICS countries growing stronger. But global governance in the United Nations system, the sole institution that can represent every nation, still represents a world that no longer exists anymore, with Africa and the Muslim world deeply underrepresented. Furthermore, some representatives still think that the G7 can represent a strategic meeting, while even the G20 plays a scarce and purely economy-oriented role.

The world has changed, and we must adapt our strategies and responsibilities accordingly. As Alcide De Gasperi once said, the way we are going to deal with these crises will influence not just the next election, but also how future generations will grow and judge us. I am deeply convinced that, as history has taught us, we can only win if we work together and stay united.