Ian Bremmer is President of Eurasia Group and GZERO Media and author of ten books, most recently, Us vs Them: The Failure of Globalism (2018), a New York Times bestseller. You may follow him on Twitter @ianbremmer.

Ian Bremmer is President of Eurasia Group and GZERO Media and author of ten books, most recently, Us vs Them: The Failure of Globalism (2018), a New York Times bestseller. You may follow him on Twitter @ianbremmer.

THE Donald Trump era will go down as the most significant domestic stress test that the United States has endured since the Civil War. Trump spent the last four years pushing American democratic institutions to their limits; some buckled, a few broke, but others stood fast. All the while, political divisions in the United States deepened—not all of which can be directly attributed to Trump, though he certainly did not help matters. As the United States rounds into the 2020s, the country is more polarized than ever, and with some of its most critical political institutions severely weakened. If President Joe Biden aspires to return the United States to any kind of global leadership role, he must first begin by addressing the multiple domestic challenges the country faces.

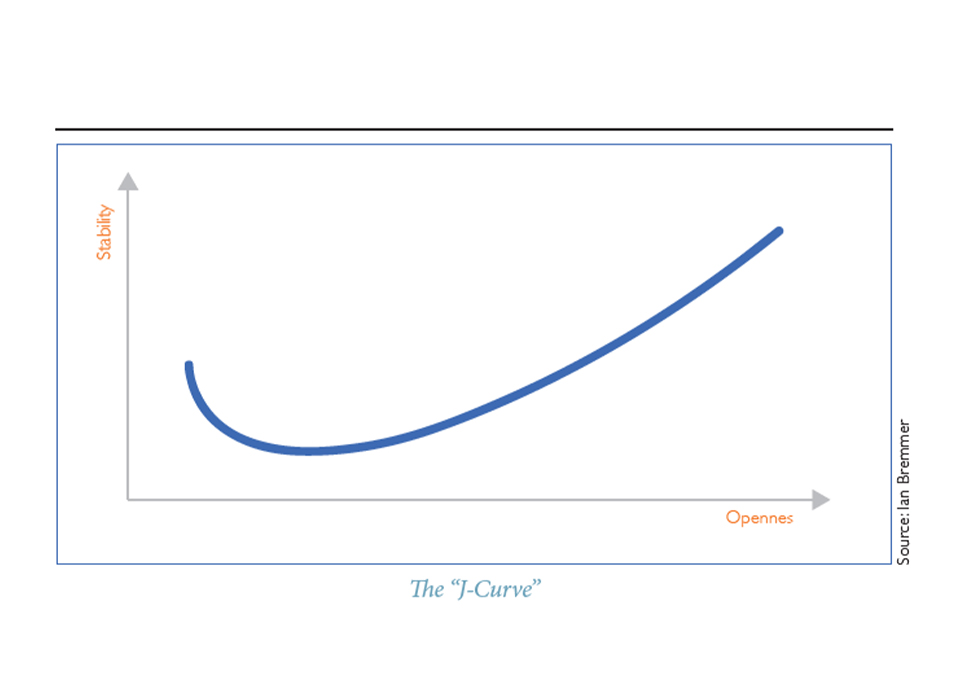

Many moons ago, I devised a method for understanding the relationship between a country’s political stability and its openness to the rest of the world. The fundamental observation that underpinned my analysis was this: there are some countries that manage to be politically stable because they largely avoid interacting with the rest of the world (think North Korea, and to a lesser extent Venezuela and Iran). Other countries are able to maintain political stability exactly because their extensive ties to the outside world mitigate the worst aspects of their domestic politics when things go awry. The “J-Curve” graph is the result.

Countries like North Korea, Venezuela, and Iran are on the left-hand side of the curve; the world’s advanced industrial democracies tend to be on the right-hand side. Moving from a closed system to an open one, or vice versa, is inherently dangerous for political stability, represented by the dip in the graph above. Up until the 2016 election, the United States was situated on the far right of the “J”, but the Trump years have seen it slowly begin to slide down, both in terms of openness and in terms of stability. Before discussing why the United States is so uniquely divided among advanced industrial democracies today—and it is, even without Trump leading it—it is necessary to examine the current state of American political institutions through a tripartite categorization: the standouts, the weakened, and the damaged. Each will be addressed in turn.

The Standouts

First, the military. No American institution proved itself as well as the military over the last four years. Military leaders in the United States consistently thwarted Trump’s worse impulses—from hastily withdrawing troops stationed in the Middle East to his threats of deploying soldiers onto American streets to quell Black Lives Matter protests. There were stumbles, of course, most notably the incident in Lafayette Park in Washington, DC where protestors were forced out in the presence of U.S. Defense Secretary Mark Esper and General Mark A. Milley, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, for the sake of a photo-op. But when Trump spent the last few months of his presidency trying to subvert the 2020 election results (leading to the January 6th, 2021 Capitol riots), the Joint Chief of Staff as an institution responded by issuing a tacit but firm rebuke of its Commander in Chief, reaffirming their oath to the U.S. constitution (“we support and defend the Constitution”) and ending any possible speculation that the military would intervene on Trump’s behalf (“On January 20th, 2021, in accordance with the Constitution, confirmed by the states and the courts, and certified by Congress, President-elect Biden will be inaugurated and will become our 46th Commander in Chief.”).

Second, the judiciary. Much like the military, the courts stand out for acting as a firm and consistent check on Trump’s most egregious policies; the last months of them swatting down attempts to overturn the election results further underscored that point. Plenty will complain about the process through which judges were confirmed during the Trump years, both at the federal and Supreme Court levels, but that is more a criticism of politics than anything else: once they took their respective places on the bench, judges exercised their judicial independence consistently, ruling in the direction that their interpretation of the law took them rather than bending to outside political influence.

The Weakened

First, the civil service. For all of Trump’s complaints about the “deep state” conspiring against him, much of his frustration was with the career bureaucrats whose positions in government are supposed to supersede allegiance to any one political party. Trump began and ended his presidency demanding unwavering loyalty from all he came in contact with, which made the relationship between him and the civil service fundamentally untenable; the decline in morale among officials at the U.S. State Department and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control was particularly notable. The election of Joe Biden and a return to more traditional American politics looks likely to stem the tide of defections and keep the country’s most capable and engaged civil servants still serving the public interest of the United States. But another president in Trump’s mold could very well change that.

Second, the U.S. Congress. The legislative branch of the American federal government had not just one but two opportunities to prove they were up to the task of executive oversight, and they failed both times to follow through on impeachment. But the erosion of Congress as an institution goes beyond the last couple of years; redistricting (or “gerrymandering,” depending on your political stance), a continuous need for fundraising, and the deep-seeded polarization of the American electorate has made it more difficult than ever for legislators to work on a bipartisan basis to sustainably address problems facing the American public. All this has had the effect of further delegitimizing the Congress, which helps explain why just 13 percent of the country has confidence in the institution today.

Third, the electoral process. Both nationwide elections in which Trump has been a candidate have been “rigged,” according to the losing side—a state of affairs that bodes serious problems for the future of American democracy. In 2016, it was Democrats who claimed that Trump was an illegitimate president, charges that ranged from criticism of the U.S. Electoral College (one that produced a U.S. president that lost the popular vote) to active interference in the electoral process from foreign actors. Four years later, it was Republicans crying foul with (baseless) claims of voter fraud. Yet while the process to certify Biden’s legitimate election victory was contentious (to put it charitably), it still worked, proving there is still some resilience left in the processes through which Americans elect their national leader.

The Damaged

First, the executive branch. More than any other American political institution, the executive branch of government is defined by the person leading it. And given Trump’s three most defining personality traits—corruption, incompetence, and a genuine affection for authoritarianism—the stature of the U.S. executive branch undeniably suffered over the last four years as Trump publicly fawned over strongman leaders and used the powers of his office to enrich himself in plain sight (e.g. taxpayer money spent at Trump properties). The good news? Those same Trump character traits (particularly incompetence) limited the amount of lasting damage he could really do while in office (alongside the civil service, the courts, and the military). The bad news? Trump conclusively proved that an executive branch constrained by norms and customs rather than laws is an executive branch that is barely constrained at all.

Second, the media. Did social media ruin our public discourse, or did our public discourse ruin social media? Wherever one comes down on that question, the reality is we now live in a world where algorithms are the most important driver of public information, a system that reinforces our prior political beliefs and makes it near-impossible to constructively engage with any information that runs counter to them. And there is no shortage of actors—both foreign and domestic—willing to take advantage of this reality to spread slanted news and misinformation for the sake of furthering their own political goals; or, frankly, just for capturing more advertising revenue. This is one of the biggest systemic threats facing the United States going forward—and one that is hard to overstate, as will be discussed further below.

World’s Most Divided Democracy

This is not all to say that the United States is in danger of sliding so far down the J-curve that it is about to become an authoritarian state; it isn’t. But there is no denying that American political stability has taken a significant hit in recent years.

One of the things most useful about the J-Curve is that it is an assessment that accounts for differences between political systems; democracies can rise and fall along the J-Curve just like authoritarian states can. But what happens individually within countries matters plenty as well. And there are features of American society that gives further cause for concern, and underscores the current place of the United States as the world’s most divided advanced industrial democracy.

We can begin with the media landscape, as mentioned above. While all democracies with open internet have to contend with the way social media and algorithms are reshaping their citizenry and the information flowing to them, the United States has a harder task than most given that the West’s great technology powers are all based in America. That means more lobbying and capture of politicians in Washington; it also means more involvement in day-to-day politics.

For example, while multiple world leaders have said noxious things over social media, it was Trump’s incitement of the January 6th, 2021 Capitol riot that made him the first world leader banned from Twitter, a move that has generated criticism across the political spectrum. Tech companies are embroiled in US politics like nowhere else, and their economic size and importance to social discourse makes extricating them from US politics particularly difficult. All the while, their echo chambers drive political divisions ever-deeper.

Another feature of US politics dividing the American electorate is the country’s reluctance to earnestly grapple with its history of structural racism. There are plenty of countries with their own shameful pasts of racism and repression of minorities, but the United States stands out for avoiding any serious reckoning with that legacy for generations, particularly in the country’s South. This has given rise to both legitimate grievances among the country’s black population (a consequence of which is the rise in popularity of Black Lives Matter), while more recently also giving rise to fears of displacement among the traditionally privileged white class that fears being shunted to the side.

The emerging reality is a system of deepening identity politics that will take generations to address earnestly, while we just saw that these very real divides took a single U.S. presidential term to inflame. And there are plenty of opportunistic politicians who will attempt to seize on these divisions to further their political aims even it causes serious harm to the country as a whole.

Finally, there’s the evolving nature of capitalism, and the unique nature of its American variant. Broadly speaking, labor is being increasingly disassociated from capital across the world, largely a result of technological advances and the continued pursuit of more profits. But the rise of automation and AI does not just take away factory jobs; it has also given rise to a gig economy that over time will come to define an increasingly large share of our day-to-day economic lives. That is a problem the whole world faces, not just the United States.

But the American version of capitalism—one that deifies and promotes the brilliant individual and visionary over the collective well-being of workers—exacerbates the dangers that are inherent in this economic transition. The traditional “American story” has been one of pulling yourself up from your bootstraps: of refusing government assistance to persevere and “make it on your own.” On the one hand, this popular conception of American capitalism has resulted in the United States becoming the world’s largest economy and coming to stand at the forefront of global technological innovation. On the other hand, it led to an economic system in which healthcare and social safety nets are treated as secondary concerns by the United States government rather than being understood as constituting some of its most critical functions. This has also led to the political capture of these issues by big business and special interests, which in turn has fueled the kind of economic anxiety that we have seen repeatedly spill into the country’s politics.

This will continue happening as we go forward.

The last four years have exposed many of America’s key frailties. And while the vulnerabilities of the political institutions of the United States have existed for years, they required an unorthodox leader like Trump to throw them into sharp relief. Those institutional vulnerabilities—paired with the socioeconomic challenges posed by race, capitalism, and the media—will take longer than a single presidential term to be addressed in earnest. This means that the United States is going to spend much of the 2020s focusing inwards more than it has in any of the decades since World War II, as it begins to address its own issues and systemic challenges.

That is a problem for the rest of the world—whatever you think of American global leadership abroad, at least it provided some form of stability and direction. But when the world’s most powerful country—in terms of military strength, in terms of economic might, in terms of innovation—is divided among itself, it cannot lead abroad. This will invariably make addressing key global challenges requiring global cooperation that much more difficult. The not so roaring 2020s indeed..., but if the United States is serious about looking inwards and addressing its own shortcomings, the 2030s may not be too bad.