Kevin Rudd became President and CEO of the Asia Society in January 2021 and has been president of the Asia Society Policy Institute since January 2015. He served as Australia’s 26th Prime Minister from 2007 to 2010, then as Foreign Minister from 2010 to 2012, before returning as Prime Minister in 2013. This is an edited and updated version of a speech delivered in December 2020 titled “China Has Politics Too: The Impact of Chinese Domestic Politics and Economic Policy on the Future of U.S.-China Relations” and an essay published in the FT Chinese titled “The New Geopolitics of China’s Climate Leadership.” You may follow him on Twitter @MrKRudd.

Kevin Rudd became President and CEO of the Asia Society in January 2021 and has been president of the Asia Society Policy Institute since January 2015. He served as Australia’s 26th Prime Minister from 2007 to 2010, then as Foreign Minister from 2010 to 2012, before returning as Prime Minister in 2013. This is an edited and updated version of a speech delivered in December 2020 titled “China Has Politics Too: The Impact of Chinese Domestic Politics and Economic Policy on the Future of U.S.-China Relations” and an essay published in the FT Chinese titled “The New Geopolitics of China’s Climate Leadership.” You may follow him on Twitter @MrKRudd.

THE year 2020 was a devastating one, a year of plague, turmoil, and loss. It was also a year of great change and transformation, as the world adapted with difficulty to meet challenges largely unprecedented in living memory, and the trends of global power appeared to shift beneath our feet. Whether from fear or dark humor, it has even been described as the year of the apocalypse. This may be more accurate than most consider: the word apocalypse, after all, means “revelation,” stemming from a Greek word literally meaning to pull the lid off something, uncovering what lies beneath.

The year 2020 was like this in more ways than one. It pulled the lid off the true extent and meaning of our globalized, interconnected world; it revealed the dysfunction present in our institutions of national and international governance; and it unmasked the real level of structural resentment, rivalry, and risk present in the world’s most critical great power relationship—that between the United States and China.

The year 2020 may well go down in history as a great global inflection point. For that reason alone, it’s worth looking back to examine what happened and why, and to reflect on where we may be headed in the decade ahead—in what I describe as the “decade of living dangerously.”

For the dangerous decade ahead, several major themes emerge from this apocalyptic 2020. First, the descent of the U.S.-China relationship into Thucydidean rivalry as the balance of power continues to close militarily,

economically, and technologically, and with Taiwan and the South China Sea still looming as the most likely clash points. Second, the urgent need to find a new framework to manage these dangers, while providing room for full strategic competition as well as sufficient political space for continued strategic collaboration on climate, pandemics, and global financial stability. Third, the continued absence of global leadership as the great powers turned inward and against one another, leaving a vacuum waiting to be filled, as reflected in the failure of multilateral and international institutions at a time when they were needed most.

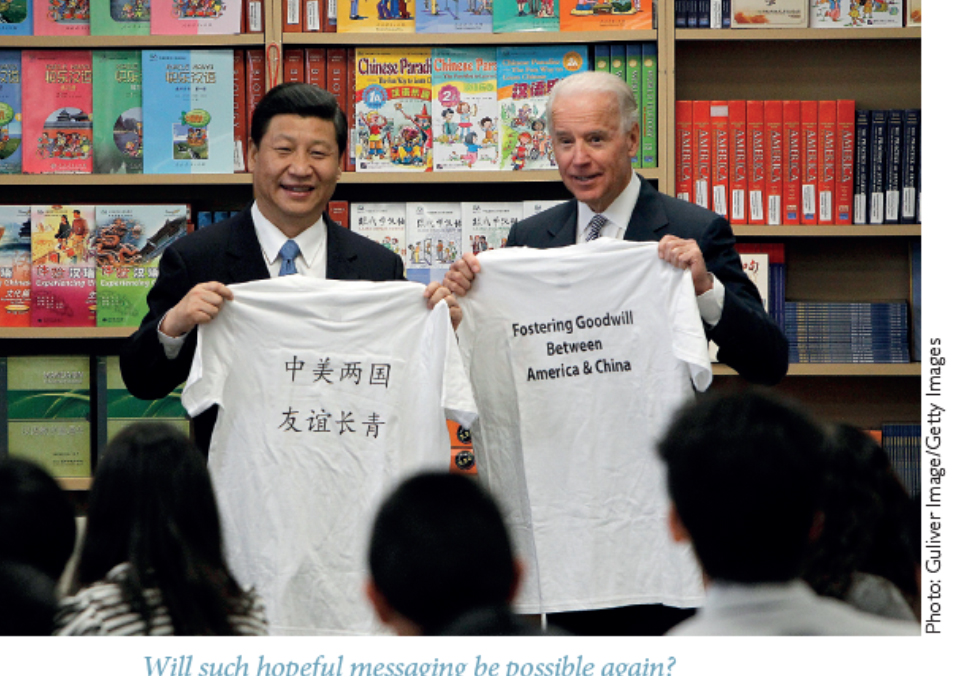

Fortunately, there are positive signs on these fronts. In Washington, the newly arrived Biden Administration has moved quickly to make effective multilateralism a key pillar of its foreign policy. In Beijing, Xi’s commitments on climate change and investing in a “sustainable recovery” from the global COVID-19 recession are welcome developments. But much, much work remains to be done.

As we enter the second quarter of 2021, the world has many reasons to be hopeful that with effort a better path forward can be forged in the decade ahead. To understand where we might be headed, it is necessary to take a look back at how we got here.

This essay will focus on three crucial issues in the year of the apocalypse, aiming to uncover what lies beneath. First, by providing the necessary background to how Xi Jinping managed to strengthen his domestic political position. Second, the political ambition that came out of the Fifth Plenum meeting of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Central Committee in November 2020, which will likely go down in history as a major turning point for China and the world. And third, by examining how that boldness has translated into a new determination by Xi Jinping for China to make a bid for true global leadership for the first time—and why the issue he chose is climate change.

Xi’s announcement in September 2020 that China will aim to achieve carbon neutrality before 2060 marked an important new milestone, signaling that it was not just willing to be a participant in the international fight against climate change but now aspired to be seen as a global climate leader. Deng Xiaoping’s 30-year-old

dictum of “hide your strength, bide your time, never take the lead” is well and truly over. This marks an important new era for the geopolitics of China’s leadership, but also one in which Beijing must understand that it will be judged more sharply than ever before, including by its developing country compatriots. And with President Biden having taken office in the United States with a wide-ranging and ambitious program to tackle climate change both domestically and internationally, climate also looms as a test case for whether a new balance of cooperation and competition between Beijing and Washington is possible.

China Has Politics, Too

While both America and the world were transfixed by the U.S. presidential election on the third of November, very few people would have noticed that just five days before, China concluded a major meeting of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party that outlined the core elements of Chinese political and economic strategy for the next 15 years.

The truism is true: our Chinese friends do think in the long term. We in the West find ourselves captured by a combination of the electoral cycle and the news cycle. This highlights one critical difference between China, the United States, and the West: notably, the difference between what is tactical as opposed to what is strategic.

It is, of course, natural that the world would focus on who would become the 46th president of the United States. This is not just because of the political theater that U.S. presidential elections represent. It’s because U.S. domestic politics drives U.S. foreign policy, international economic policy, and strategic postures across the Asia-Pacific region and the world.

And if anyone thought that somehow domestic policy and foreign policy were clinically separate domains, I offer as “Exhibit A” the experience of Donald Trump as the classic counterproof. Trump’s politics and personality radically impacted American policy toward the world at large.

But just as American domestic politics matter, so too do Chinese domestic politics. The political systems may be radically different. But the truth is that the internal politics of the CCP also radically impact the course of Chinese economic policy, foreign policy, and national security policy. And should anyone doubt this proposition, I offer “Exhibit B” as the counterproof: the impact of Xi Jinping on China’s international posture over the past seven years.

Despite this fact, there is a predisposition, both in the United States and elsewhere in the world, to simply take Chinese politics as some sort of “given.” This is a wrong conclusion. Chinese politics has never been static. It is constantly changing, although the patterns of change may be less evident to the untrained eye.

We in the democratic world need to radically lift our understanding of what makes the CCP tick. Perhaps it’s because we are so obsessed with our own politics that we just don’t care. Or we assume that the CCP is monolithic, notwithstanding the fact it now has 92 million members and a multiplicity of factions. Or perhaps it is thought that Chinese statecraft is somehow eternal, somehow detached from the series of bloodbaths and political reversals that have colored the history of the CCP since its founding in 1921. Or maybe we just think it’s all too hard to make sense of Chinese internal politics, that it’s all too impenetrable and even inscrutable.

This mindset must change. China is on course to become the largest economy in the world this decade and is already a peer competitor with the United States militarily in East Asia. And what China now does with its economy, environment, and climate will also deeply shape the world for decades to come.

And all of the above are deeply influenced by the worldview of one man: Xi Jinping.

2020: The Year That Was

Xi Jinping, like China itself, has had a tumultuous year. For Xi, the year began appallingly with the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in Wuhan and its rapid spread to other parts of the country and then the world. Xi’s domestic political position came under increasing challenge. He was criticized internally for the failure of the initial efforts to contain the virus on the grounds that local officials were too hesitant to report the truth to central party officials under Xi for fear that they would be punished for being the deliverers of bad news. This was despite the fact that a supposedly “failsafe” system had been established after the SARS pandemic of 2003. This system was meant to immediately report any future coronavirus outbreaks to the center—just like the center had supposedly directed the closure of all Chinese wet markets following the SARS outbreak 17 years ago.

Xi Jinping was also under pressure for a slowing economy, not only because of the impact of the virus, which ground most of the economy to a halt in the first quarter of 2020, followed by a creeping recovery during the second quarter. Xi was also criticized for having brought on the trade war with the United States, which had also begun to slow domestic growth, as well as a range of other domestic economic policy settings after 2015 that had gradually eroded private sector confidence, contributing to collapsing private fixed capital investment, and slowing growth.

By the middle of 2020, with the world also rounding on China for having “exported” the virus to them, Xi Jinping found himself under considerable domestic pressure. But, if a week is a long time in politics, 12 months is an eternity. A year following the outbreak in Wuhan last November or December 2019, the virus has by and large been brought under control across China.

Furthermore, China’s economy in the second half of 2020 recovered rapidly, with annual economic growth coming in at 2.3 percent, which made it the only major world economy to grow in the year of the pandemic. China is now distributing its vaccines to countries across the developing world at a time when the United States does not appear to have yet turned the corner on its comprehensive COVID disarray.

Indeed, from Beijing, America’s political system has been seen as dysfunctional, its economic recovery questionable, and its overall international standing undermined as a consequence of its comprehensive mishandling of the pandemic.

The net effect of all the above is that Xi Jinping, whose domestic political position was in considerable difficulty earlier this year, now finds his position strengthened. Xi Jinping’s continued political ascendancy was underlined by the Fifth Plenum Meeting of the Central Chinese Committee, which concluded on October 29th, 2020. Judging by the Plenum’s outcome, Xi’s political ambition to remain in power for the next 15 years looks increasingly secure.

China also looks to be in a better position to surpass the American economy over the course of the 2020s, accelerated by the rapid pace of the Chinese recovery.

And the 2020s increasingly appear to be the decade when Xi Jinping will want to see the realization of reunification with Taiwan. Indeed, a little noticed op-ed by a senior party official in early November 2020 stated, “It may be difficult to achieve the goal of cross-strait unification without using military force.” No one has used that sort of language about Taiwan at senior levels in Chinese politics for more than 40 years.

For these reasons, the 2020s loom as the make-or-break decade for the future of Chinese and/or American power. Whatever each country may publicly declare as being its strategic objectives in relation to the other, the reality is that deep strategic competition between Washington and Beijing is already well underway.

And the prize at stake is who gets to write the rules of the international order for the rest of the twenty-first century—not just in the rarefied world of foreign policy, and not just for the international institutions that form the current rules-based system, but also who gets to set the standards for the new technologies that will drive and, in some cases, dominate our lives for decades to come. In many ways the test case, so to speak, for all this ambition is climate change—China’s first-ever bid for true global leadership on any issue.

The 2020s therefore will be very much the decade of living dangerously for us all.

Chinese Politics During 2020

The Fifth Plenum of the 19th Central Committee in October 2020 was ostensibly about economics. It was to approve the party’s formal recommendations for the content of the 14th Five-Year Plan, which will be formally considered by the National People’s Congress in March 2021. And while the economic content of the next Five-Year Plan is important, the primary significance of the Plenum was politics. It laid the foundation for the 20th Party Conference in November 2022, which will formally determine whether Xi Jinping will become, in effect, leader for life.

What the text of the Plenum communiqué reveals is that Xi Jinping’s political position has become even further entrenched. The adulatory language used at the Plenum about Xi Jinping was deeply reminiscent of that used for Mao. Xi was referred to as China’s “core navigator and helmsman.” The last time the word “helmsman” was used to describe a Chinese political leader was in reference to the “great helmsman” (Weida de Duoshou) Mao Zedong himself at the height of the Cultural Revolution.

Central Committee members also showered Xi Jinping with praise, including Xi’s “major strategic achievement” in the handling of the COVID-19 pandemic. Most important, however, beyond the public sycophancy toward Xi, was the fact that the Plenum did not nominate a successor. In recent decades, it had become “normal” practice for China’s leaders to use the Fifth Plenum of the Central Committee during their second term in office to indicate who was most likely to succeed them. For example, under the previous party General Secretary Hu Jintao, at the Fifth Plenum of the 17th Committee in 2010, Xi Jinping was appointed vice chairman of the Central Military Commission, thereby making it plain to all that he would be inheriting Hu Jintao’s mantle.

No comparable appointments were made during the Fifth Plenum in 2020. It is, therefore, the most formal indication so far that Xi Jinping will seek to remain in office for a third term and probably beyond, thereby finally breaching the convention laid down by Deng Xiaoping that party leaders should only remain in office for two terms, thereby avoiding the problem that arose with Mao in the last 20 years of his career.

Xi Jinping had already paved the way for this change back in 2018 when the National People’s Congress formally amended the constitution to allow the Chinese president to exceed a two-term limit. However, the decision by this Plenum not to appoint a successor to Xi Jinping provides the final formal proof that this is now his clear intention.

Lest there be any doubt on this question, Xi Jinping has also spent a large part of 2020 eliminating any real or imagined political opponents. There have already been a range of purges, imprisonments, arrests, removals, or demotions of individuals who have been critical (or at least seen to be critical) of Xi Jinping’s policy course.

Most spectacular among these was the investigation of Vice President Wang Qishan’s former chief of staff, Dong Hong, who had worked closely with Wang for 20 years between 1998 and 2017. This has been a remarkable development. Wang Qishan and Xi Jinping had previously been regarded as close, with Xi entrusting Wang with the leadership of the party’s anticorruption campaign between 2013 and 2018. Indeed, Dong Hong worked for Wang in this capacity. Dong’s arrest is a shot across the bow for any potential political challenger to Xi’s authority, including those closest to him.

In June 2020, Xi also launched a new “Party Education and Rectification Campaign” targeting the Party’s legal and security apparatus in particular. Chen Yixin, the secretary-general of the party’s Political and Legal Affairs Commission—which oversees China’s law enforcement bodies—was more explicit. In his words, the goal of the campaign was “pointing the blade inward, to completely remove the cancerous tumors, remove the evil members of the group, and ensure that the political and legal team is absolutely loyal.”

In October, Chen said that the “three month pilot program” of the rectification campaign was ending, but only to consolidate so that a “nation-wide rectification can begin next year.” He highlighted that, so far, 373 officials had been put under formal investigation and 1,040 others disciplined. “Rectification of political and legal teams has entered a critical period of investigation and correction,” he said.

Therefore, in 2021, the year during which preparations for the critical Party Congress of 2022 will be most intense, the party’s internal security apparatus is about to be reminded that Xi Jinping means business.

The series of purges that have occurred across these security-related institutions over the past seven years reflect the fact that Xi Jinping has never believed that this central part of the Chinese Communist Party’s internal machinery was fully under his control. Indeed, in Beijing, it was widely believed that these institutions had been the last redoubt of former General Secretary Jiang Zemin, despite Jiang having left office in 2002. One of Xi Jinping’s political hallmarks is that he never leaves anything to chance.

As soon as Xi Jinping took power, he conducted widespread purges of the senior leadership of the People’s Liberation Army with the anticorruption campaign, replacing them with his own appointments of people he believed to be “absolutely loyal” to his command. Xi had earlier also brought the People’s Armed Police (China’s massive paramilitary force) under the direct control of the CCP, removing it from the control of the State Council, where it had long enjoyed a level of institutional autonomy.

Finally, Xi Jinping succeeded at the most recent Plenum in promoting six new members of the Central Committee. All six are very much Xi Jinping’s men. These are the party’s secretaries in Hubei, Zhejiang, Shaanxi, and Liaoning and the governors of Shanghai and Shandong. The promotion of “Xi’s people” has been unfolding rapidly in the six weeks since the Fifth Plenum.

These actions build on a range of measures already implemented by Xi Jinping in his first seven years in office that consolidated more and more political power in his own hands. Xi has been described as “the chairman of everything.” He is personally chairman of all the major leading groups of the party that in any way deal with significant policy questions. He has also relegated the status of Premier Li Keqiang and the State Council (China’s cabinet) to a secondary and sometimes peripheral role. Under Xi, power has been relocated to the center.

This is also consistent with Xi Jinping’s more general assertion of the centrality of the party’s political and ideological rule over the country, the economy, and society at large. The opportunity for any form of policy, let alone political dissent, outside the internal organs of the party has now been severely circumscribed. This now also extends to the universities, civil society, the media, and even international organizations (e.g., the investigation of the most recent president of Interpol, Meng Hongwei).

National Security Prioritized

Afurther innovation of the recently concluded Party Plenum, and the recommendations for the 14th Five-Year Plan that the communiqué outlines, has been the large-scale expansion of the party’s security control machinery. The communiqué states: “We will improve the centralized, unified, efficient, and authoritative national security leadership system, [...] improve national security legislation, [...] and strengthen national security law enforcement.” Tellingly, the communiqué also explains that the party now sees security as the key factor in China’s future development. As it states: “We have become increasingly aware that security is the premise of development and development is the guarantee of security.”

This was also visible when Xi hosted a November 2020 meeting on crafting new national security directives, when Xi stressed the necessity of achieving “security” in every facet of China’s existence, including “economic security, political security, cultural security, social security, and ecological security.”

Minister of Public Security Zhao Kezhi gave a much more detailed explanation in a long People’s Daily op-ed published on November 12th, 2020. “The public security organ,” he said, is the most “important tool of the people’s democratic dictatorship and a ‘knife handle’ in the hands of the party and the people. Politics is the first attribute and politics is the first requirement.” It was their job to “firmly grasp the eternal root and soul of loyalty to the party” and to “focus on building and mastering public security organs politically, and to earnestly implement absolute loyalty, absolute purity, and absolute reliability as the only thorough and unconditional political requirements” along with being “absolutely loyal to the CCP Central Committee with Comrade Xi Jinping as the core.” Zhao concluded that would require giving “full play to the role of ‘knife handle’” to “resolutely defend the long-term ruling status of the Communist Party of China.”

Xi Jinping’s determination to extend security control across most aspects of Chinese life has also been reinforced by rising geopolitical tensions with the United States. Guo Shengkun, the Politburo member who heads the party’s Central Political and Legal Affairs Commission, drew an explicit link between the party’s internal and external security challenges in another article in November 2020. He stated that “we must firmly safeguard the state’s political safety, regime safety, and ideological safety” and “we must defend against and strike hard on sabotage, subversion, and splitism by hostile forces.”

For Xi Jinping, the reality of geopolitical tension with the United States has both fortified and, to some extent, helped justify domestically his preexisting determination to assert maximum control over Chinese politics, media, business, academia, and society.

It is important to note that no previous Chinese Five-Year Plan document has ever included a section dedicated specifically to national security. That has now changed. Of itself, this underlines China’s worsening external environment; the threat (in Beijing’s mind) now posed to China’s future national development; and the justification, therefore, for the securitization of everything.

Major Turning Point

As noted, the Fifth Plenum is remarkable for what it says about both Chinese politics and economics. The Plenum celebrates the fact that China has now achieved the first of its twin centenary goals—that is, for China to become “a moderately prosperous society” by the centenary of the

establishment of the Chinese Communist Party in 1921. The second of the centenary goals, scheduled for 2049 on the centenary of the People’s Republic itself, is for China to achieve the status of a fully developed economy.

Over the past year or two, however, Xi Jinping has been advancing a new intermediary goal for 2035. And for the first time, in the October Plenum document, Xi outlined his blueprint for turning China into a “great modern socialist nation” over the course of the next 15 years.

The plenum document indicates that Xi now intends to accelerate China’s second centenary goal—making China into “a modern socialist country that is prosperous, strong, democratic, culturally advanced, and harmonious” by the end of 2049—to at least majority completion by 2035.

This was underlined a week before the Plenum by Li Junru, former vice president of the Central Party School of the Communist Party, who said that Xi believed China’s economic success “allows us to now have a very good foundation for the basic realization of modernization proposed by Deng Xiaoping 15 years ahead of schedule.” He also indicated that the Fifth Plenum would be “a major turning point” for China’s path to modernization.

In 2035, Xi will be 82. This is the same age as Mao at his death. Therefore, it seems Xi is aiming to see his vision realized before his own passing—and quite possibly before the end of his own time in power.

Finally, Xi Jinping’s campaign to continue in office for another three five-year terms, his expansion of party control across Chinese politics and society, as well as his broadening of the powers of the party’s national security apparatus have been reinforced by a parallel campaign to ramp up popular nationalism.

In a strikingly fiery speech on October 23rd, 2020, Xi used the commemoration of China’s entry into the Korean War to harness Chinese nationalist sentiments against future external threats.

Xi quoted Mao calling China’s “victory” in the Korean War against the United States as “a declaration that the Chinese people had stood firm in the East, and an important milestone in the Chinese nation’s march toward the great rejuvenation.” Xi also stated that the correct lesson from the Korean War was that “seventy years ago, the imperialist invaders fired upon the doorstep of a new China, [...] that Chinese people understood that you must use the language that invaders can understand—to fight war with war and to stop an invasion with force, earning peace and respect through victory and that the Chinese people will not create trouble, but nor are we afraid of trouble, and no matter the difficulties or challenges we face, our legs will not shake and our backs will not bend.”

In the same speech, Xi added that “Once provoked, things will get ugly,” and that China will “never allow any person or any force to violate and split the motherland’s sacred territory [...] for once such severe circumstances occur, the Chinese people shall deliver a head-on blow.” And finally, in a pointed jab at the United States, he declared that “Any country and any army, no matter how powerful they used to be” would see their actions “battered” by international sentiment if they stood against China.

Earlier, on September 3rd, 2020, Xi had spoken at a ceremony commemorating the 75th anniversary of the end of the war against Japan, where he declared the five things the CCP could “never allow.” First, for anyone to “smear” the party or its history; second, for anyone to “deny and vilify” the party’s achievements; third, for anyone to “impose their will on China through bullying, or change China’s direction of progress”; fourth, any obstruction of China’s “right to development”; and fifth (and most importantly), any attempt to “separate the CCP from the Chinese people.”

In a new book of previously unpublished Xi speeches released on September 6th, 2020, titled Discourses on Preventing Risks and Challenges and Responding to Emergencies, Xi also warns of “the treacherous international situation” that China faces, and “an intensifying contest of two ideologies,” with the United States desperate to Westernize and split China as the global balance of power shifts in China’s favor.

To conclude, Chinese domestic politics over the course of 2020 went through its own radical cycle: from a leadership that was, in many respects, reeling from the impact of COVID-19 and economic implosion in the first part of the year to a leadership that by year’s end was committed to the further consolidation of Xi Jinping’s power as well as the strengthening of the overall control of the party.

This does not mean that internal opponents to Xi Jinping’s political, economic, social, and foreign policy measures have disappeared. They have not. But they have been placed in check by Xi Jinping’s superior political craft. As I’ve written many times before, within the brutal politics of the Chinese Communist Party, Xi Jinping is both a master politician and a master Machiavellian. His ability to identify where the next political challenge will come from, and how to prevent it and/or outflank it, has proven to be formidable.

History Is on His Side?

The China of the future is becoming increasingly different from the China of the pre-Xi Jinping past. And he well may prevail, particularly if U.S. strategy continues to fail.

Alternatively, many factors are still at work within China itself that could cause Xi’s domestic strategy to unravel: a radical polarization of domestic political opposition as a result of the harshness of the party rectification campaign to be unleashed in 2021; a Chinese private sector that embarks on a private investment strike in response to diminished business confidence; a large-scale, system-wide financial crisis, driven by excessive indebtedness and bank and corporate balance sheets that are no longer able to cope; further natural disasters, including a possible repeat coronavirus pandemic, given that these have occurred periodically in China’s recent past; or an unanticipated national security crisis with the United States that erupts into a premature conflict or even war.

Xi Jinping, however, believes that history is on his side. Xi is a Marxist determinist who believes in the twin disciplines of dialectical and historical materialism. For these reasons, he believes that China’s continued rise is inevitable, just as the relative decline of the United States and the West is equally inevitable.

The critical variable for the future is what the Biden Administration and its friends, partners, and allies around the world now do. The recent record of U.S. policy has been less than impressive. But President Biden has assembled a formidable domestic, economic, and international policy team. They certainly have the intellectual capacity to grasp the complexity of the interrelated challenges (both foreign and domestic) that they face.

The question is whether, as Alexis de Tocqueville observed in a previous century, the politics of this curious American democracy, and its permanent predilection for divided government, will accommodate the strategic clarity and resolve that will be necessary for America to prevail.

An early test case is turning out to be climate change.

Geopolitics of Climate Leadership

The origins of China’s newfound desire to play a leadership role in the global fight against climate change can be traced back to 2014, when Xi Jinping and U.S. President Barack Obama made a landmark joint announcement on climate change. This event took place less than three weeks before CCP’s Central Conference on Work Relating to Foreign Affairs in the same year, which is when China embarked on a new era of confident, independent international policy activism under Xi’s leadership.

Since then, China has shown a steady determination to demonstrate its own climate credentials, which increasingly has become a bright spot in China’s position on the world stage. Yet, Xi’s announcement in September 2020 that China will aim to achieve carbon neutrality before 2060 marked an important new milestone. For the first time, China has signaled it is not just willing to be a participant in the international fight against climate change, but that climate leadership has crossed the geopolitical Rubicon in Beijing’s eyes. In other words, it has become a central priority for China irrespective of the steps taken by other countries, including the United States.

This marks an important new era for the geopolitics of China’s climate leadership but also one in which Beijing must understand that it will be judged more sharply than ever before, including by its developing country compatriots. This is especially the case as President-elect Joe Biden takes office in the United States with a wide-ranging and ambitious program to tackle climate change both at home and abroad.

To best navigate these newfound expectations and responsibilities, China will need to significantly bolster its short-term efforts to reduce emissions through its 2030 Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) under the Paris Climate Agreement, especially with regard to its future use of coal. Piecemeal steps forward, such as those foreshadowed by Xi in December 2020, will be insufficient in the eyes of the international community. At the same time, China must demonstrate a propensity to achieve Xi’s vision of carbon neutrality as close to 2050 as possible and start to seriously reorient its support for carbon-intensive infrastructure overseas through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Without these steps, any goodwill generated by Xi’s September 2020 announcement risks quickly becoming a thorn in China’s side because of the geopolitical benchmarks it has now set for itself. The lack of any such evidence of a shift in short-term thinking towards Xi’s long-term vision in the recently published 14th Five Year Plan does not therefore bode well in this regard.

Ecological Civilization

While it was President Hu Jintao who first used the phrase “ecological civilization” in 2007 to describe China’s own brand of environmentalism, it is Xi who has made it part of the party’s lexicon and a key pillar for the country’s development. In doing so, Xi has deliberately sought to differentiate China’s approach from traditional Western notions of liberal environmentalism. This includes by underscoring the economic importance of environmental action, as evidenced by his regular pronouncement that “clear waters and green mountains are as valuable as mountains of gold and silver,” a phrase Xi first used in 2005 when he was party secretary in Zhejiang province.

Until now, domestic imperatives have been driving China’s creeping environmentalism. The single greatest inspiration for the change in behavior between the China the world grappled with at the UN Climate Conference in Copenhagen in 2009 and the China that was instrumental in the securing of the Paris Climate Agreement in 2015 was rising concerns among the Chinese population about the level of air pollution in their cities. Declaring a “war on pollution” during the opening of the 18th National Party Congress in March 2014 underscored this.

However, that same year, Xi’s rhetoric also started to emphasize the international

imperatives of climate action. This included his declaration that “addressing climate change and implementation of sustainable development is not what we are asked to do, but what we really want to do and we will do well.” Nevertheless, China remained cautious, as demonstrated by Xi’s decision not to attend a climate summit convened by former UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon in September 2014, which was billed as the most important moment in the lead-up to Paris.

Nevertheless, in 2015 and 2016, Xi embarked on an intensive environmental reform effort within the party, including through embedding the concept of “ecological civilization” in the 13th Five-Year Plan and pitting it alongside the concepts of the “Chinese Dream” and the “Two Centenary Goals,” including doubling China’s GDP by 2020. China’s vision of ecological civilization was also a central concept in the 2015 NDC it tabled as its first commitment under the Paris Agreement.

This helps demonstrate why, by January 2017, just days before the inauguration of President Donald Trump (who was elected on a platform that included withdrawing the United States from the Paris Climate Agreement), Xi was prepared to use an address to the World Economic Forum in Davos to signal China would nevertheless stay the course with the agreement. The significance of Xi’s statement at the time should not be underestimated. If China had chosen to use Trump’s formal confirmation in June 2017 of his intention to withdraw America from the agreement as an opportunity to obfuscate on its obligations—or worse to also seek to withdraw from the agreement altogether—it is unlikely that the agreement would remain intact today. For that, the world owes China a debt of gratitude.

A New Era

Xi’s announcement in September 2020 that China will achieve carbon neutrality before 2060 marks an important new era for the geopolitics of China’s climate leadership. Xi’s announcement was his most important speech on climate change since his January 2017 address in Davos and his November 2014 joint announcement with Obama.

For most of the Trump era, China’s approach to the international fight against climate change had been akin to that of a substitute teacher. Beijing had never signaled a desire to do more than simply cover the field in Washington’s absence. Important initiatives such as the establishment of the Ministerial on Climate Action (MoCA) alongside the EU and Canada were more at the behest of Brussels than Beijing. And for Beijing, this was an easy win until the breakdown in relations with Ottawa beginning with the arrest of Huawei’s Meng Wanzhou in late 2018, which made the optics of cochairing this forum difficult.

However, the September 2020 announcement demonstrated that China’s diplomatic calculation had changed. With a deadline looming later this year for countries to respond to the Paris Climate Agreement’s invitation to develop long-term decarbonization strategies for mid-century, and to enhance their short-term climate targets (NDCs), few expected China to make any serious pronouncements on either before the outcome of November’s U.S. presidential election was clear. And in the event of a Biden victory, Beijing would still have a sweet spot between November and January to make announcements to head off future pressure from a Democratic administration in Washington. The fact Xi decided China should nevertheless be prepared to adopt—for the first time—a clear pathway to decarbonize its economy was therefore hugely significant.

The fact that Xi’s announcement also made no reference to China’s traditionally hard-held bifurcation

between developed and developing countries’ responsibilities—or indeed linked China’s actions in any way to the actions of others—was also very significant. Xi’s dismissal of the Europeans’ attempts to extract such an announcement just a week earlier during a virtual EU-China leaders’ meeting underscores that he clearly now sees greater geopolitical value in China’s preparedness to signal its desire to act alone compared with the domestic value of being seen to use minor steps by China as a lever for extracting stronger commitments from the developed world in return.

New Geopolitical Benchmarks

The challenge for China now is to live up to the new geopolitical benchmarks it has set for itself in the eyes of the international community. This includes among its G77 developing country compatriots, not the least of which the many island nations whose very existence hinges more than anything else now on the actions of developing countries such as China, but also India (with Xi’s announcement, India is now clearly forecast—for the first time—to become the world’s largest emitter). In other words, China will now be judged on an increasingly level playing field with the United States, the European Union, and regional powers like Japan, rather than simply rewarded for coming to the table.

At the same time, China will need to be conscious that any goodwill it has built up in recent years for staying the course with the Paris Climate Agreement will quickly be eclipsed by the weight of Biden’s own ambitions. This includes his determination to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050, aggressively ramp up U.S. short-term action through a new 2030 emissions reduction target, and completely decarbonize the domestic energy system by 2035.

China would be wise not to cut against this, given the troubles with the wider bilateral relationship. It is in both countries’ interests to rebuild the cooperative relationship on climate change they established under the Obama Administration, and which Biden—and his Special Presidential Envoy for Climate, John Kerry—played a key role in creating. From Biden’s perspective, any attempt to address climate change without China doing more will inherently remain limited.

From Beijing’s perspective, a cooperative relationship will help take the heat out of U.S. attempts to extract additional efforts by China, including with regard to its domestic use of coal and the Belt and Road Initiative—as well as potentially the implementation of carbon border tax adjustment policies and the like. Through a new framework of managed strategic competition, this can also be achieved while the overall relationship remains difficult. Indeed, climate change can be the topic that protects against the “decoupling” narrative across the board, and which builds a cooperative bridge to the United States and the broader West.

This will require a sophisticated approach by China, including overcoming its traditionally tin-eared response to the views of the international community on its climate credentials, and instead to demonstrate a willingness to understand genuine areas of geopolitical weaknesses on climate and to seek to overcome them.

Mid-Century Ambition

First, China would be well advised to confirm through its formal depositing of a long-term strategy with the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change that Xi’s September 2020 announcement will cover all greenhouse gas emissions and not just carbon dioxide. According to modeling by the Institute of Climate Change and Sustainable Development at Tsinghua University undertaken during Xie Zhenhua’s leadership (before his recent appointment), and a separate study by the Asia Society Policy Institute and Climate Analytics, this would put the goal squarely in-line with the global temperature limits set by the Paris Climate Agreement, especially if coupled with deeper cuts in the short term to avoid higher cumulative emissions over time.

Ideally, China would also join the Biden Administration and the European Union, plus every other G7 economy, including Japan (and now also South Korea), in committing to reach this goal closer to 2050. Few governments have as strong a propensity for effective and centralized long-term planning as does China. The celebration of the centenary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 2049 provides a ripe milestone for Beijing to have in mind.

Short-Term Ambition

At the same time, China must be prepared to do much more to reduce emissions in the short term, including through depositing a new NDC later this year in the lead-up to COP26 in Glasgow. President Biden signed the paperwork for the United States to rejoin the Paris Climate Agreement on his first day in office, and America is likely to deposit its own new NDC in April 2021.

What is already clear is that Xi’s other announcement in September that China will now aim to peak emissions “before”—as opposed to “around”—2030 will simply not cut it in the eyes of the international community that will be looking for China to reach this milestone by 2025, while also taking action to address the three other quantitative targets contained in its existing NDC and the one to come.

China has an opportunity to ground its new NDC in a government-wide process, rather than simply present it as an effort by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE). In other words, the new NDC could help reinforce, rather than be seen to detract from, Xi’s vision of carbon neutrality. However, much of this will rest even more immediately on the decisions China continues to take as part of its economic response to COVID-19. The approval of a large number of new coal-fired power plants in 2020 does not augur well for ensuring there is a green economic recovery, even with Beijing’s investment in so-called “new infrastructure” such as electric vehicle charging stations and rail upgrades. Indeed, the total capacity of coal-fired power generation now under development in China is larger than the remaining operating fleet in the United States. And while many had hopes that the delivery of the 14th Five Year Plan would bring with it additional ambition in the short-term to reduce emissions, the reality is that it did not go any further than a number of incremental improvements Xi announced in December 2020 to China’s existing 2030 goals. The development of a special FYP for climate later in 2021 provides another important window of opportunity. The possibility of the U.S. and China forging a cooperative lane for engagement on climate change also has the potential to help deliver additional ambition.

The Belt and Road Initiative

A third area that will require a sophisticated reset by Beijing concerns the Belt and Road Initiative, and especially China’s support for large amounts of carbon-intensive infrastructure around the world, including coal-fired power stations. By some estimates, China is currently involved in the construction of more than 100 gigawatts of coal-fired power stations around the world, including in South East Asia, Africa, and even Eastern Europe.

While some would counter that China’s support of coal actually extends far less than that of Japan or South Korea, this is not the case when considering foreign direct investment alongside development financing and the exporting of equipment and personnel. In fact, most estimates would put the ledger at least two-thirds in the direction of China, and only likely to get worse as Japan announced in July 2020 that it would not finance any new coal projects abroad. South Korea’s parliament is also looking to put in place a ban on its own financing, including after the state-owned utility Kepco announced it would scrap two coal projects in the Philippines and South Africa.

Beijing should be careful not to underestimate the extent to which this has the potential to significantly impinge on BRI—the jewel in the crown of Xi’s foreign policy—in the years ahead. Already moods are shifting in many recipient countries. The awarding of the prestigious environmental Goldman Prize to Chibeze Ezekiel for organizing his fellow Ghanaians against plans for a Chinese-supported coal plant in that African nation provided a powerful example of this. And this attitudinal shift will only accelerate once additional and more accessible sources of clean energy financing become available.

President Biden has not only pledged on the campaign trail to shine an uncomfortable light on China’s offshoring of emissions through BRI, but his commitment to massively ramp up America’s overseas clean energy investments also has the potential to result in a sophisticated diplomatic squeeze on China. If China does not want to be seen to be moving only at the behest of U.S. pressure, it would be well advised to begin to make these reforms earnestly.

While the recent effort ostensibly overseen by MEE to establish a “traffic light” system for new BRI projects is welcome, it will require more teeth to be effective. Ultimately, the most powerful thing China could do would be to follow Japan’s and South Korea’s lead and halt its overseas support for coal entirely. The economic hard heads in China will find that difficult, especially as the country winds down its domestic coal sector and seeks to redeploy its human and financial capital in the sector elsewhere. But the extent to which China can at least extend many of the laws and regulations it has put in place domestically in recent years to equally apply to its overseas projects will be an important first step.

None of this should take away from the fact that Xi’s announcement in September 2020 marked a new era for the geopolitics of China’s climate leadership. Gone are the days when China would be lauded for simply coming to the table, or for holding the table together in the absence of the United States. The decisions that China takes now as the world’s largest emitter will be judged increasingly on the same playing field as those that the United States is prepared to take, as well as the rest of the international community.

Whether China’s leaders understand this new geopolitical paradigm remains to be seen. The decisions they take in the period ahead with regard to China’s 2030 NDC and toward Xi’s vision of reaching carbon neutrality will be the clearest indicators of this, as will the reforms they are prepared to put in place around the Belt and Road Initiative. Piecemeal steps forward will no longer cut it, including in the eyes of their developing country compatriots.

Xi’s legacy as a climate leader in China may be assured. But his legacy as a climate leader internationally is not yet guaranteed. This is a key international opportunity for China and a key international opportunity for Xi. It is also one that aligns with the country’s domestic interests of upgrading its economy, cleaning up its environment, and shoring up its energy security.

We will see how this plays out in the 2020s—our decade of living dangerously in which the contest between the United States and China will enter a decisive phase that will be characterized by growing tension and intensified competition. Even amid the inevitable escalation to come, there will be some room for cooperation in a number of critical areas. One of the most mutually advantageous surely ought to be climate change, a common planetary challenge. Certainly, Xi Jinping hopes that greater cooperation on this issue will help stabilize the U.S.-China relationship more generally—a common planetary hope if there ever was one.