Stefan Antić is Managing Editor of Horizons and a Senior Research Fellow at the Center for International Relations and Sustainable Development. You may follow him on X @StefanAnticRS.

Stefan Antić is Managing Editor of Horizons and a Senior Research Fellow at the Center for International Relations and Sustainable Development. You may follow him on X @StefanAnticRS.

At the risk of resorting to clichés while describing the state of the world in early 2024, the words that come to mind are ‘fragmented,’ ‘de-globalizing,’ and increasingly ‘conflict-ridden.’ Yet, what matters more than slapping on an appropriate label is how the world’s actors—be it states, alliances, or organizations—will survive and prosper in its changing structure. The formats of cooperation that will emerge in the coming years as successful or failing models will be crucial in shaping the world order for the better part of the twenty-first century.

After a decade of unproductive summits that relied on the international system as we knew it during the height of the unipolar moment, the world of global multilateral formats is gone. Some relics of old multilateralism, which include the United Nations, will remain for the sake of preserving the bare minimum of communication required between main stakeholders, and maintaining the necessary contours of international law. However, these institutions will not fundamentally shape dynamics in different corners of the world, where ad hoc, issue- and interest-driven smaller partnerships have already emerged as more effective frameworks of conducting policy and projecting power. Somewhat appropriately titled “minilateralism,” this type of coordination among states holds promise of delivering on the pressing needs of various actors in the absence of a truly international structure.

A map of CEFTA participating countries

As of 2024, minilateralism already presents itself as a series of geopolitical rallying points. Minilateral arrangements are predisposed to exhibit a multitude of overlapping priorities, sometimes even inviting the participation of the very same actors in multiple rival projects. While such behavior is certain to occasionally annoy and disgruntle great powers, minilateral formats may enable the big and powerful to advance their international initiatives and protect vital interests where they may be endangered. But these minilateral arrangements, in turn, favor the policy visions of most middle powers even more, since their value increases exponentially within such groups. Furthermore, it provides them with the luxury to cherry-pick the best features of all worlds, selecting suitable partners for each issue without many repercussions for other relationships maintained by middle powers. Moreover, it shields them from the difficult position of having to choose sides in conflicts that will be supported, if not altogether ignited, by great powers.

But what about small states? How will the minilateral geopolitical trends affect them? Are they destined only to rally behind major security guarantors to preserve peace? Is joining major economic blocs the only hope such states have of achieving development? Should they be allowed to formulate minilateral partnerships of their own, or are these too unavoidably tied to supervision of the more powerful states and supranational blocs? These and other questions pose real dilemmas to the countries of the so-called “Western Balkans,” as transatlantic elites have often referred to non-EU states of Southeast Europe.

Besides its leftover reputation from the wars that accompanied the dissolution of Yugoslavia in the 1990s, the Balkans has also come to be known for its endless accession to the EU. The sheer fact that the region needed to be included in the European Political Community and compelled to accept the bloc’s “revised enlargement methodology” is—in the eyes of the Balkan elites and the general public—a formalization of the EU’s enlargement fatigue. While such developments are by no means “the end of the world” for the accession-weary Balkan nations, the region’s realities leave its people with very few other options to turn to. Yet, in an age in which minilateralism abounds across the globe, the answer may very well lie in turning to each other. Available evidence suggests that this is what Balkan countries are indeed attempting to achieve, although questions remain about how much of this occurs at their own initiative. The EU, which has long overseen and directed regional efforts on trade, tariff elimination, and administrative reform, completely surrounds the Balkan states that have not yet become its full members. Thus, while Brussels might not be ready or willing to drive further enlargement in the region, it certainly remains willing to engage with it and determine its future trajectory. In this, the EU is complemented by the efforts of the United States, which has maintained and expanded its role as the region’s security patron. As neither Brussels nor Washington are expected to abandon their formidable roles any time soon, the question remains whether one should expect Balkan minilateral formats to take an independent course.

CEFTA: Early Days of Economic Integration

Unsurprisingly, most post-Yugoslav initiatives in the Balkans started out as economically themed. On the one hand, this was indeed a pressing need for all the countries involved. Small and relatively isolated economies showed little potential for long-term growth and development on their own, especially with hard borders in place, their respective regulatory systems unadjusted for free market capitalism, and their individual sectors uncompetitive. On the other hand, doing political or any other form of integration bordered the impossible. In addition, most Balkan states had border disputes with each other, while some, like Serbia, couldn’t exercise sovereignty on the entirety of their internationally recognized borders—highlighting the much talked about Kosovo status issue that persists to this day. Furthermore, these countries maintained different narratives even about the region’s history, let alone the events during the conflicts of the 1990s. Whether the argument was purely economic or somewhat political, it was certain the region needed a mediator. It also needed guidance on free market practices with which it had no prior experience. Naturally, searching out a completely new model of market integration for troubled Balkan economies was beyond anyone’s ability at the time—be it in the Balkans, or the international community at large.

Even in the early days of their economic integration, the Balkan countries inherited a cooperation model previously practiced elsewhere: the Central European Free Trade Agreement (CEFTA). CEFTA was first established in 1992 as a mechanism for fostering economic integration among Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia. At the same time, the agreement played major roles in stimulating the transitions of these Central European systems towards free-market economies and preparing them for their integration with their wealthier Western European counterparts. As the list of aspirants to join the EU expanded, so did the involvement of new countries in CEFTA, each of which eventually left the agreement upon gaining EU membership. This was a logical step for the Balkans as well, with its countries following suit in 2006 as part of a rebranded CEFTA 2006 agreement. Importing this ready-made plan promised quick growth under clear rules and seemingly neutral supervision of a third party. Understandably, this was a perfect arrangement for everyone involved. While the region’s countries struggled to find common ground on a host of issues, they were united in a single political goal to eventually join the EU. For its part, the EU acted as an economic regulator in another region that couldn’t meaningfully affect its policies but could provide preferential access to a valuable emerging market. It is thus safe to say that EU member states, along with the bureaucrats in Brussels, held all the keys to the bloc’s relationship with the Balkans.

Indeed, this has by no means been a one-sided relationship. The years that followed also proved that CEFTA yielded substantial benefits for the previously fragmented Balkan economies. In a comprehensive 2015 paper for Acta Oeconomica, scholars Radmila Dragutinović-Mitrović and Predrag Bjelić observed a 44-percent increase in bilateral trade among Balkan CEFTA participants since the signing of the agreement. Similarly, the same paper found that CEFTA increased “trade by about 25.3 percent on average” between any two member countries only in the first five to six years since the agreement’s entry into force. More importantly, CEFTA has since truly unlocked the region’s investment potential, with billions of euros flowing in both from its participating states and third countries. Serbia holds the record as the largest economy in the region, having received €42 billion in foreign investment between 2007 and 2021 alone, according to its Development Agency. The Foreign Investment Promotion Agency of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the region’s second largest economy, documents a total of €8.8 billion invested over a similar period. Similar trends can be observed in North Macedonia, where its National Bank’s data indicates that €7.01 billion worth of investments have been made as of the end of 2022. Further, the U.S. Department of State claims that Albania, with a smaller-sized population than the two largest Balkan economies, has been receiving an average of $1.19 billion in annual investments between 2016 and 2021—a tangible achievement for a small-sized economy.

With economic indicators showing constant growth in investment and job creation, Balkan countries embraced the CEFTA integration project and have not officially abandoned it to this day. The trade and investment schemes initially exhibited very little downside, while the path forward appeared clear and unburdened by whatever mutual disputes the countries may have had on the political and security fronts. Yet, as time went on, the CEFTA arrangement began to show some structural issues. On the economic side, trade imbalances and reduced competitiveness of certain sectors emerged as the main problems. As Nina Vujanović, an economist at the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, notes in her 2023 report on the first 15 years of CEFTA’s implementation, “prior to the agreement, many economies had greater export competitiveness in the primary industries.” While she also notes that new advantages have been gained in the knowledge economy and services, the fact remains that certain advantages have been lost due to this integration project, leading to some restructuring and job loss.

In the Balkans, where relations between states are already strained, even simple market forces favoring the larger and more developed economies can be a source of tension. Needless to say, the tendency of such market forces to create long-term economic disparities may only add fuel to the fire. After all, it is no secret that smaller and less economically developed CEFTA signatories have been extracting fewer benefits as a result of this arrangement. According to the Serbian Government’s publicly available data, the country achieved a $2.71 billion trade surplus with CEFTA participants in 2023. While this is in itself a result of legitimate trading within the established rules, some smaller-sized economies of the region have been known to drag their political grievances into the project, bemoaning Serbia’s dominant position. Still, Serbia too grapples with enormous dependencies on the EU (as does the rest of the region). As Vujanović’s report points out, Serbia, the economy that is most “integrated with EU value chains,” relies rather heavily on goods, services, and components from the EU. Moreover, the share of Serbia’s exchange with the EU has increased exponentially over the years, reaching 54 percent of total trade this Balkan country conducted in 2022. A trend that CEFTA has only supported, and a tool that Brussels has been able to utilize for political conditioning if necessary.

From a political perspective, CEFTA has demonstrated vulnerability to pressures and unilateral actions. This has been most evident as tensions flare on the issue of Kosovo. The Provisional Institutions of Self-Government in Kosovo, a CEFTA participant as “UNMIK Kosovo” since 2007, unilaterally declared independence in 2008. As the world remains split on the legitimacy and legality of their attempted secession, so too is CEFTA, whose members Albania, Montenegro, and North Macedonia recognize it as an independent state, while Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Moldova do not. As an instrument to raise stakes whenever a dispute with Belgrade escalates, the Provisional Institutions in Priština have twice resorted to tariffs and trade blockades. Citing Serbia’s “destructive behavior” as a pretext, Priština first introduced 100-percent tariffs on products from both Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2018, which encountered harsh reactions from EU officials, who dubbed the move “a clear violation of CEFTA.” Similarly, in 2023, Priština reacted to the arrest of its three police officers in Central Serbia by imposing a trade blockade on Serbian goods. While the EU officials again called for de-escalation, the blockade remains in place at the time of this writing. This revealed the reality that such disputes cannot be adequately solved within the CEFTA framework.

The way it is structured today, the CEFTA Secretariat lacks the wherewithal to impose adequate measures against any party that violates the 2006 agreement. To avoid being perpetually tied down by consensus-based decisionmaking, CEFTA’s main proponents have endeavored to reform the framework’s Dispute Settlement Mechanism (DSM). According to the material released by CEFTA, a new DSM is meant to be “rule-based, independent, impartial, and ultimately able to achieve compliance and guarantee enforcement.” Whether such a DSM will be proven enough to extend the life of the current framework remains to be seen. In the meantime, known violations of the agreement continue with impunity. Failure to deliver on a feasible DSM is sure to eventually result in a replacement of the framework—a hint of which one can already observe in the Open Balkan initiative, despite claims to the contrary.

The Open Balkan Initiative

Circumventing inefficient deals has always been the force and motivation behind the establishment of new international formats, minilateral or otherwise. Such is the story of the Open Balkan initiative, borne out of inefficiencies of the EU accession process in the Balkans, and the fact that CEFTA does not offer much beyond free trade. Imagined, and at first introduced, as the “Mini-Schengen,” the Open Balkan was first revealed to the public in October 2019, when Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić, then Prime Minister of North Macedonia Zoran Zaev, and Albania’s Prime Minister Edi Rama met in the northern Serbian city of Novi Sad. After two more meetings in Ohrid, North Macedonia and Tirana, Albania, which followed in November and December of the same year, the three officials eventually signed an agreement inaugurating the initiative on July 29th, 2021, with Serbia, North Macedonia, and Albania as its founders. Since those days, much has been said about this seemingly minilateral initiative, ranging from cautious optimism to outright accusations of serving as a backdoor for Russian influence in the region. So, what signs has the initiative exhibited since its founding?

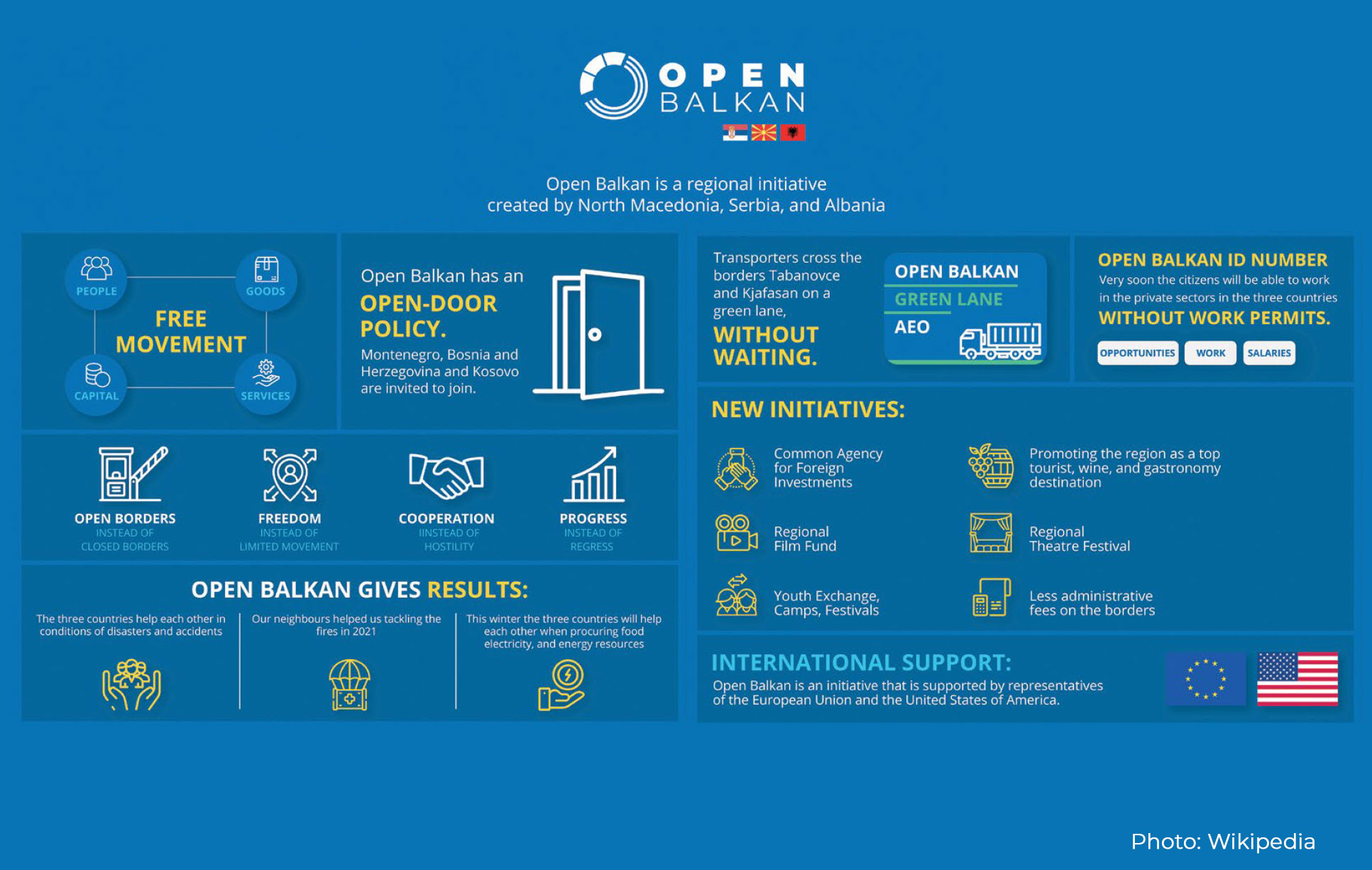

Features of the Open Balkan initiative

The creators of the Open Balkan initially presented the initiative as an attempt to replicate the four freedoms enjoyed in the European single market within a smaller regional format. Portrayed like this, the initiative should in theory impose itself as an upgrade of the CEFTA framework, eliminating residual barriers to a Balkan single market and opening a unified labor market—a step that had previously been envisioned only as a prerogative of EU member states. While the new framework also assumes the form of a minilateral arrangement—focusing on an interest-based set of goals and involving a limited number of partners—it too has enjoyed the support of the European Union and the United States. This in turn reinforced previously held suspicions that no independent geopolitical projects in the Balkans would come to fruition without the (at the very least tacit) approval of Washington and Brussels. Since the Open Balkan project overtly mimics best practices of Western institutions, this tripartite initiative already exhibits signs of strategic alignment with the West, irrespective of whether its efforts will result in full EU integration or a standalone Balkan project.

However, not everyone appears to be convinced of such a trajectory. Paradoxically, opposition to the initiative has been the most vocal among those parts of Balkan elites that have long advocated an uncompromising Euro-Atlantic path for the region. Their arguments have to some extent been that the project hinders further EU accession, giving it up in exchange for a smaller consolation union. Others have sought to influence the West and its position on the project by pointing to alleged Russian influence. For instance, Albin Kurti, currently serving as Prime Minister of Kosovo’s Provisional Institutions, argued in a 2021 interview for Montenegrin daily newspaper Pobjeda, that “the Open Balkans is more like the Balkans that is open to influences from the East, especially from the Russian Federation and China; open to autocracy, corruption, war criminals […] All of this [is] contrary to European values of democracy and rule of law.” Yet as Kosovo still maintains a significant NATO military presence and a large American base on its territory, Russian influence, especially in the shadows of a small regional initiative, is at worst a manageable problem. Kurti’s motivation to rally Western support likely lies in posturing for the ongoing Belgrade-Priština dialogue, where he is eager to extract as many concessions as possible from his interlocutors. In a similar vein, during his final year in office and facing a difficult election campaign, now former President of Montenegro Milo Djukanović labelled the initiative as “very controversial,” interpreting Serbia’s prospective economic gains within the project as a direct threat to Montenegrin statehood. But as evidence now shows, it was the former president’s deep-seated policy of division that aggravated the electorate to the point of demanding change at the top. As the 2023 election results have demonstrated, Djukanović may have appealed to people’s fears one too many times.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, where three dominant ethnic groups have traditionally struggled to come up with a unified position on any issue, the Open Balkan project has been no exception. This regional format was wholeheartedly welcomed by the country’s Serbs, while resulting in discontent among Bosniaks, and somewhat mixed signals from Croats. But as Bosnian economists of all ethnicities continue to lay out the benefits of the framework, there are signs that the mood in Sarajevo may shift. As is the case with other distrusting, post-conflict regions, the Balkans suffers from a chronic condition of confirmation bias. In other words, people tend to see what they want to see. Worse yet, they see what they fear most. To that end, Serbia has been widely acknowledged as the country that stands to profit the most from the Open Balkan initiative due to its ability to produce most high-value goods and the sheer size of its economy. For those with reservations about Belgrade’s intentions, this has amplified fears about growing economic disparities and dependence on Serbia, which eventually may be exploited for political ends. Still, Serbia too has had its share of skeptics. With ethnic Albanians being the only group with substantial population in all three Open Balkan states, some Serbian public figures have stoked fears of a reinvigorated “Greater Albania” project. Since the Open Balkan envisions no supranational structures to enforce such policies, it is worth recognizing that this mostly economic arrangement has many limits. The way it is structured, grandiose geopolitical projections are certainly not in the cards.

Fears and known economic trajectories aside, there are many things the Open Balkan is not. Despite its leaders boasting about a single labor market in the Balkans and the freedom of movement, nearly three years of the initiative’s existence have demonstrated its limits in upgrading existing forms of economic integration. In terms of conducting trade, what the Open Balkan does is reduce waiting times at the border crossings, streamline and centralize inspection systems, and ease the bureaucracy that usually accompanies inter-state transport. This easily translates into greater volumes of goods traversing borders more quickly and generating more profit for all the parties involved. The Open Balkan further helps create a common economic area, which in tangible terms comes short of a customs union, let alone an EU-style single market. Still, greater integration attracts more investment and access to the whole area, providing (especially foreign) investors with additional incentive to continue doing business in the Balkan market. On an individual level, citizens of the three founding member states are allowed to visit each country with their ID cards only, although their allowed stay has not been extended indefinitely. In fact, the previously established limit of 90 days within any 180 day period very much remains in place. Perhaps most importantly, the Open Balkan initiative strives to significantly simplify the procedures for obtaining work permits. Now available as an online procedure, all it takes is for a citizen of a member state to access their e-government account, fill out a form, and receive an ID number that allows them to look for work in another Open Balkan state. While this looks and sounds simplified, work permits have not been completely abolished, which is another discrepancy with EU practices.

One of the main reasons the Open Balkan was formed in the first place was labor shortage. Coupled with existing unemployment levels, these issues continue to pose real dilemmas to Serbia, North Macedonia, and Albania. Since investors increasingly struggle to find qualified workers, importing workforce has long been on the minds of the region’s policymakers. Therefore, creating something resembling a single labor market was not just a logical choice but a necessity, as it clearly allowed importing labor both from other Open Balkan participants and third markets. Furthermore, ethnic structures and cultural backgrounds of the three countries significantly complement the single labor market idea. As ethnic Albanians inhabit both North Macedonia and Southern Serbia in large numbers, this population represents a valuable pool of talent for the Albanian market. Similarly, such exchanges had long existed between Serbia and North Macedonia before eventually being interrupted by the breakup of Yugoslavia. It only made sense for the two nations to re-establish them now.

Another important feature of this Balkan initiative is its intergovernmental format of cooperation. Since its official inauguration in 2021, the initiative’s founders have signed a series of agreements, protocols, and memoranda—some of which were bilateral. In the scope of these documents, Open Balkan states have regulated many areas besides trade and labor market access. These include cooperation in protection against natural disasters; veterinary and food security; trilateral cooperation of accreditation agencies; mutual recognition of academic qualifications; as well as cooperation in tourism, culture, and tax administration. Most documents have already been ratified in these countries’ respective parliaments, becoming embedded as national laws. While this form of cooperation appears less complex than a supranational structure, it helps protect the initiative from falling victim to political disagreements too early. In other words, as much as political issues between countries are prone to destroying common institutions, this cannot be done as long as there is no institution to be destroyed. As Serbian economist Mihailo Gajić explains, “these are individual sectoral agreements created between member countries. Therefore, [the] ‘Open Balkan’ would cease to exist only if the countries decide[d] to repeal the laws through which these agreements were adopted in parliaments…”

Convenient as the initiative’s methodology may be for preserving its past achievements, it’s difficult to imagine the Open Balkan evolving into a fully political union. The reason for this is simple: its members have just too many conflicting strategic aims. These differences exist even between its founding members. For instance, Serbia and Albania, which share the goal of eventually joining the EU, could not be more different on their security visions for the region. Albania has been a NATO member since 2009 and wishes to see the entire Balkans under the same security umbrella. Conversely, Serbia declared its military neutrality in a 2007 parliamentary declaration, a policy it maintains to this day. Despite making gains in regional economic cooperation, neither Albania nor North Macedonia share Serbia’s views on what its borders are. The Kosovo status issue poses additional problems for the future of the regional initiative. Absent Serbia’s full recognition of the Provisional Institutions’ claim to statehood, it would be hard to find a modality for the inclusion of Kosovo in the initiative. Since the Open Balkan currently prioritizes intergovernmental agreements as a primary mode of formalizing deals, such documents would continue to be signed between parties that recognize each other as equals. Besides Serbia, Kosovo would not be able to count on such arrangements when dealing with Bosnia either.

Additionally, there are plenty of international issues that the initiative’s current and prospective members disagree on. The region frequently attempts to align views when it comes to voting in the UN General Assembly, usually following the lead of most EU member states. Yet, here too, dissenting voices can be heard. As far as rhetoric and actual policy go, Balkan countries have shown vastly different attitudes towards the Israel-Hamas War and the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian conflict. On the UN General Assembly resolution proposed by Jordan in October 2023, calling for humanitarian aid to be delivered in Gaza, Bosnia and Montenegro voted in favor, while Serbia, Albania, and North Macedonia abstained. Just within Bosnia and Herzegovina, one can find irreconcilable differences on international conflicts. Unsurprisingly, the Serb majority entity Republika Srpska has repeatedly expressed its support for Israel after the October 7th, 2023 attacks. In the country’s capital of Sarajevo, however, signs of support for Palestine are regularly displayed, both in the streets and within institutions. The list goes on. Even as all Balkan states stand united in recognizing Ukraine’s territorial integrity, Serbia refuses to impose sanctions on Russia, despite its alignment with EU sanctions policy on a host of other states. Finally, as another nail in the coffin of irreconcilable political differences, Open Balkan states do not share the vision on what their joint initiative should become. With some goals of a common labor market already achieved, Albanian Prime Minister Rama has declared the initiative’s mission “accomplished.” Meanwhile, Serbia’s President Vučić continues to boast about a bright future awaiting the Open Balkan.

The future of the Open Balkan does not need to be bleak though. While deeper political integration may be off the table for the time being, economic integration has already shown promising signs. The fact that minilateral arrangements are anything but uniform leaves one wondering about how the Open Balkan initiative should be classified. As a project enjoying overt support (and at times guidance) of the EU and the U.S., it lacks the necessary autonomy for a twenty-first-century minilateral format. However, as an economic initiative, it displays a degree of courage and self-interest needed for a small group of states attempting to elevate their status. What makes this initiative unusual as a minilateral framework is that its main aim is not to augment power but to rescue an otherwise untenable situation. For all its faults, the Open Balkan could serve as a testing ground for other minor powers that might—or already do—find themselves with very few geopolitical options. Even as a middle step towards a larger alliance or structure, such minilateral initiatives provide valuable insights into what it takes to make a small nation’s voice heard and its goals more prominent. In a fragmented world of shifting geopolitical realities, alternatives may eventually rise to replace old arrangements. In the meantime, even survivalist minilateralism will be worth serious consideration.

Weighing Alternatives

Navigating minilateralism is an exceedingly complex endeavor, especially when participants lack sufficient strategic autonomy or sovereignty to spearhead larger-scale geopolitical projects. The question that naturally presents itself is what minilateral avenues can minor powers carve out for themselves? The reality is that some options are available, but as previous paragraphs have demonstrated, they often come predetermined by more influential states or blocs. The continuing challenge for small states engaging in minilateralism lies in the necessity of assembling a truly sizable coalition to wield substantial influence on the international stage. The Balkan context would thus uncompromisingly require the inclusion of all of its actors. However, as the number of participants grows, so does the complexity of aligning future policies. In the Balkans, where strategic alignment borders the impossible, this challenge is particularly pronounced.

Agreeing on minilateral security arrangements remains a formidable obstacle in such contexts, as there is simply no mini-security pact to be had in the Balkans. NATO’s dominant presence in the region, with all but Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina as members, highlights this problem even more. Paradoxically, Serbia’s potential accession to the alliance is hindered by one of the latter’s best achievements. NATO prides itself on providing security guarantees under Article 5 and safeguarding territorial integrity of its member states. But Serbia cannot count on such support while an overwhelming majority of NATO countries opposes its sovereignty over Kosovo. Similarly, multiple hurdles exist in political integration. Disagreements abound on most major issues, pushing the region into dependencies on third parties that stand to gain a lot in exchange for their “impartiality.” With the EU guiding the region through the Berlin Process—whose stated goal is the region’s integration in the bloc—it has positioned itself as a de facto patron of the Balkans, regardless of whether the region ever becomes part of the EU.

All this leads to the conclusion that Balkan states are not well disposed for high-impact minilateralism. As I have previously argued in a 2022 essay for The National Interest, the region’s countries have already been on a trajectory to cementing their status of “associates.” The European Political Community, which embodies this concept, has begun to institutionalize associate states, knowing that this is perhaps the most potent method of engagement in the absence of full integration of the region with the West. Should the EU fail to renew itself in the face of its own challenges, its policy of commercial engagement and political patronage towards the Balkans will only continue. Accordingly, any new regional initiatives that may come to light will inevitably face more of the same limitations. This, however, is not to say that other forms of cooperation can’t and shouldn’t be attempted. What is certain is that they would all require significant diplomatic skills of the countries involved. Additionally, they would all be immensely risky.

As is the case with other cooperation formats, the Balkans does not need to completely invent a new framework for political and security cooperation. One model of security cooperation that has already produced a desired effect is the Turkish-Azerbaijani format. Long before minilateralism started to take its present shape, Türkiye and Azerbaijan concluded the Agreement on Strategic Partnership and Mutual Support. Signed in 2010, the agreement substantially expanded the two countries’ military-technical cooperation, but more importantly vouched that each would support the other by “using all possibilities.” In reality, this translated to a replica of NATO’s Article 5, with each party committing to support the other in the event of a military aggression. As the Second Karabakh War broke out in 2020, Türkiye offered substantial assistance to Azerbaijani military operations while denying direct involvement in the conflict. However, the Turkish military played a pivotal role in supplying its ally with Bayraktar UAVs, improving Azerbaijan’s drone warfare capabilities, and ultimately defeating their Armenian adversary. The two countries have since upgraded their security pact in the scope of the 2021 Shusha Declaration, which affirms and advances the previously established guarantees. Of course, the impact of the Turkish-Azerbaijani mini-pact is much broader. By tying its security to a middle power—and also a NATO member—Azerbaijan has been able to emerge victorious in a direct conflict with Armenia and protect its sovereignty for the foreseeable future. With powers like Russia and Iran on its border, Azerbaijan’s approach to Türkiye has established a security equilibrium in the South Caucasus.

For the Balkans, there is a lesson to be learned from the Azerbaijani experience. All Balkan countries are minor powers, and most of them have resultingly sought (and found) refuge in a Western-style, zero-sum alliance that is NATO. For those that are still looking to carve out the best security outcomes for themselves, answers lie either in neutrality or minilateral arrangements.

This is especially true in Bosnia and Herzegovina, where key political actors fear either the disappearance of the country or that of their identity. Such a country is in desperate need of a security equilibrium. This can be achieved only by inviting new partners into more inclusive security agreements, which would in turn relieve the concerns of main stakeholders—both in the country and its immediate neighborhood. Bosnia’s largest neighbors, Croatia and Serbia, have long been the sources of insecurity for Bosniak political elites in Sarajevo. Crafting a security arrangement with those countries only would thus achieve the unintended effect. But as other key stakeholders of the broader region become more interested in overcoming deep-seated impasses in Bosnia, the country’s elites would be well-suited to consider their involvement for the sake of long-term stability.

Under this wildly theoretical scenario, Bosnia and Herzegovina’s security may find optimal assurances in a minilateral agreement involving NATO and non-NATO members. With no middle powers in the region wielding sufficient influence to defy major powers, this would require disciplined rallying of smaller nations. Besides Croatia and Serbia—which already serve as guarantors of the Dayton Agreement—such an arrangement would likely include Montenegro, Hungary, and possibly Romania, Bulgaria, and North Macedonia. An arrangement of this kind could address Bosniak concerns about territorial integrity, alleviate Serbia’s anxieties regarding NATO encroachment, and provide Croatia with a valuable platform of security guarantor for Bosnia’s Croats. Nonetheless, as NATO appears poised to complete its enlargement in the region, achieving this remains a daunting challenge that might never receive any consideration.

In a 2022 edition of Horizons, professor Dejan Jović argued that “the reality of being surrounded by NATO, an enemy that bombed it in 1999 […] feeds frustrations and the sense of insecurity in Serbia.” This is an accurate assessment of the collective psyche in Serbia and a reality that burdens strategic decisionmaking. In an environment consisting of minor powers, Serbia is the only Balkan country with the capability to strategically consider a self-interested initiative that could achieve its goals. Despite itself being a minor power, the national mindset, especially among the Serbian elites, has always viewed the country as something greater—and much closer to a middle power. If there was ever to be a more just, and less zero-sum, security framework in the Balkans, one could assume that Belgrade would play a most central role in it. Still, during the unipolar moment and the time since its ending, Serbia missed some opportunities to create a safer environment for itself.

The need for defense pacts arose mostly during times of crisis. In 1999, at the peak of NATO’s relentless bombing campaign against Serbia, the country (then as the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia) announced the decision to join the Union state of Russia and Belarus in a desperate bid to stop the bombing. Once the war was in full swing, the decision did not spur excitement in Moscow, for Russia’s leadership knew better than to engage in a direct military confrontation with the West. The fall of the Milošević regime that followed in 2000 brought about Serbia’s major course reversal, setting the country on a Euro-Atlantic path. Still in the union with Montenegro, the new Serbian leadership attempted to preserve the country’s territorial integrity by actively pursuing NATO membership. The years that ensued proved this to be a difficult task. Montenegrin independence was in the making, and the elites in Washington and across Western Europe were setting the stage for negotiations on the status of Kosovo, which eventually led to the unilateral declaration of independence in 2008. Since minilateral initiatives became a thing of the leaderless world in late 2010s and early 2020s, no such frameworks existed during unipolarity. From today’s perspective, however, greater leeway to advance bilateral defense and security cooperation would have been a groundbreaking development for Serbia.

Today, Serbia finds itself trying to navigate NATO-dominated Balkans, where its options are severely limited. Much like Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia’s strategic choices come down to neutrality or minilateralism, albeit with much bleaker prospects for the latter. Culturally tied to Russia and dependent on its diplomatic support to keep Kosovo out of international institutions, Serbia remains under constant Western scrutiny and criticism. However, in terms of security, its cooperation with Russia has in the past primarily revolved around procurement and emergency assistance during natural disasters. Since 2022, this too has stopped. Since Russia’s geographical distance has always made it an unlikely security partner, Serbia has utilized its membership in the Partnership for Peace program to advance cooperation with NATO members.

Going back to Azerbaijan’s experience, Serbia’s optimal minilateral partners could hypothetically be Romania and Greece, given their geographical proximity and longstanding support for Serbia’s territorial integrity. Yet, even in this theoretical scenario, the effectiveness of such partnerships is dubious. Romania and Greece lack the necessary strategic leverage to independently initiate agreements that may run counter to American strategic interests. NATO’s position in the Black Sea, to which Romania is crucial, focuses on deterring Russian hard power. Providing a backdoor of this sort to a country that is perceived susceptible to Russian influence makes it unlikely for leading NATO powers to ever support. Furthermore, as tensions frequently rise around Kosovo, Romania and Greece have no incentive to place themselves in harm’s way for the sake of Serbia. Moreover, doing so would put them at odds with many of their allies that already support Kosovo’s unilaterally declared independence. For both Bucharest and Athens, pressing priorities lie elsewhere. Besides, losing their favorable positions in the Black Sea and the Mediterranean for the sake of a minilateral arrangement was never an option.

Reflecting on Türkiye’s example in the Caucasus may lead one astray, as no neighboring country possesses the capacity to offer Serbia or Bosnia and Herzegovina the terms of the Turkish-Azerbaijani partnership. Strategic maneuvering of Balkan states thus remains constrained by geopolitical realities and the reluctance of its potential allies to challenge established Western security frameworks. The main reality that one needs to grapple with is just how powerful the middle powers are relative to the small states. India, arguably the world’s most formidable middle power, currently participates in the G20, BRICS, the Quad, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, the Asian Development Bank, the Non-Aligned Movement, and a host of other organizations—many of which have conflicting priorities and goals. While significant middle powers can hedge their bets or engage in competing geopolitical projects, no such freedom will be allowed for small states within the existing world order. The Balkans, populated exclusively by small states, seems destined to stick with Western zero-sum arrangements.

The only set of semi-minilateral projects that have shown promising signs in the Balkans are economically-themed initiatives and agreements. Yet here too, some parts of the region possess greater potential than other. Not all countries in the Balkans share such similar backgrounds, nor do they share as much history as some do. Serbia, Montenegro, and Bosnia and Herzegovina are all territories where the Serbo-Croatian language is dominant, albeit referred to in different terms due to political distinctions. Additionally, in North Macedonia, the Macedonian language bears high similarity and mutual intelligibility with Serbo-Croatian. This, among other things, is part of the reason why fluctuation of workers between Serbia and North Macedonia has been the most intensive in the scope of the Open Balkan initiative. As it’s widely known, business flourishes where language barriers don’t exist. With the exception of Albania, which stands out as culturally different, these states share a unique commonality: they all originated from the same place (Yugoslavia) and are heading to the same place (the EU)—however unlikely the latter may now appear. Thus, any economic integration mirroring the EU’s four freedoms in the region should be accompanied by cultural cooperation. This model, inspired by the pre-EU Benelux, should prioritize administrative flexibility, featuring open borders, a unified labor market, and an intergovernmental institution overseeing administrative tasks and providing employment opportunities for a new generation of Balkan civil servants.

While this initiative would not aim to exclude Albania altogether, starting without it would be easier. Unresolved issues that Albania holds with the region’s two largest economies—Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina—include divergent views on Kosovo’s status, pressing international issues, disputes on minority rights, and a wide variety of differing historical narratives. Besides, Albania is the only country with a completely different linguistic background, hindering efficient administrative collaboration. Furthermore, Albania’s geographical remoteness and divergent administrative practices from those inherited from Yugoslavia further complicate integration with other Balkan societies. While the Open Balkan initiative is commendable, its achievements are already cemented in national laws, making its legacy safe. Indeed, a new initiative such as the “Balkan Benelux” would not necessarily contradict or undermine the Open Balkan initiative. As far as minilateral arrangements go, it’s not uncommon for them to overlap and reinforce each other. This overlapping nature sometimes strengthens their effectiveness, allowing them to serve varying purposes while at some level working in concert. While the Balkan Benelux may offer a unique approach to regional cooperation, it can coexist with and even enhance the outcomes of the Open Balkan initiative. While proposed only in Serbia, where leaders of the liberal-conservative People’s Party have championed the Balkan Benelux format, its constructive nature and benefits promise swifter outcomes for all participating states. The proposed project is thus far the only one offering a pragmatic and inclusive path forward for Balkan nations, while striving to safeguard their interests, as opposed to those of third parties. Whether the project ever reaches the top levels of decisionmaking will depend on a complex web of political events in the region that are by definition all but predictable. For what it’s worth, it certainly wouldn’t be the first great idea that never saw the light of day in the Balkans.

Minilateral formats in the Balkans have faced significant limitations, primarily centered on economic themes due to irreconcilable political disagreements and the region’s security dominantly falling under the NATO umbrella. While CEFTA has been the most inclusive economically, it has struggled to adequately respond to crises and violations of the agreement. The Open Balkan initiative, which aims to create a common labor market, has shown promise, supported by both the EU and the United States. Despite some challenges that it encounters, the region continues to integrate into EU value chains, grappling with trade deficits and seeking ways to maintain economic growth and supply the regional market with enough workforce to attract further (foreign) investment. However, in spite of being proven to drive GDP growth and facilitate trade among its participants, none of these initiatives really embody minilateralism.

True minilateralism holds many advantages for middle powers, which can strategically select in which interest-driven groups to participate and how to refuse dictates of great powers on certain policy fronts. Similarly, minilateral formats allow great powers to maintain influence in specific regions and address pressing issues through “coalitions of the willing.” However, such benefits are not readily available to small states. Such examples abound in the Balkans, a region that lacks minilateral frameworks—and strategic clout needed to create them—that would allow it to increase international influence. Instead, the Balkans remains unable to escape Western zero-sum arrangements on security, while it mimics existing EU practices on economics. Despite this, some optimism remains when it comes to prospects for improvement within the existing framework, with the potential for more functional structures—like the Balkan Benelux—to emerge over time. Minilateralism appeared as a feature of a leaderless world. The fact that it remains only partially available in the Balkans signals that the region is by no means leaderless at this point. Whether and when this will change will depend on the processes that are taking place on a much larger scale.