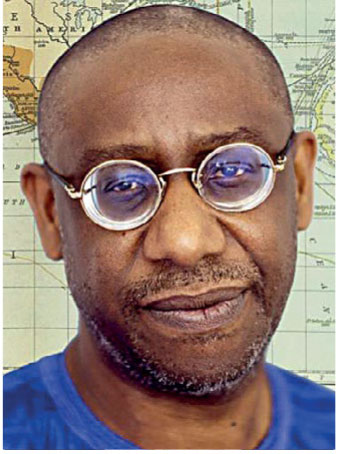

Professor Adekeye Adebajo is a Senior Research Fellow at the University of Pretoria’s Centre for the Advancement of Scholarship in South Africa. He is the author of Building Peace in West Africa: Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea-Bissau (2002) and The Eagle and the Springbok: Essays on Nigeria and South Africa (2023). He served on United Nations missions in South Africa, Western Sahara, and Iraq.

Professor Adekeye Adebajo is a Senior Research Fellow at the University of Pretoria’s Centre for the Advancement of Scholarship in South Africa. He is the author of Building Peace in West Africa: Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea-Bissau (2002) and The Eagle and the Springbok: Essays on Nigeria and South Africa (2023). He served on United Nations missions in South Africa, Western Sahara, and Iraq.

Between 1960 and 1990, 37 out of 72 (about 50 percent) military coups d’état in Africa occurred in West Africa. The subregion remains a turbulent neighborhood as instability continues to spread across Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Nigeria, Ghana, Togo, Benin, and Côte d’Ivoire. The military—a group that British scholar, Samuel Finer, described as “the Men on Horseback” six decades ago—has recently returned to power across the subregion through the barrel of a gun. Coup-making colonels and captains have, in the last two years, seized power in Mali, Burkina Faso, Guinea, and Niger, with the 15-member Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS)—founded in 1975—and the 55-strong African Union (AU) predictably suspending these military regimes from their institutions, and often announcing economic, legal, and other sanctions.

Military juntas have overthrown largely elected but sometimes increasingly illegitimate civilian governments. Several other civilian dominos could be toppled by future putschists, as harassment of opposition parties continues in countries like Senegal, Togo, and Sierra Leone. These developments suggest that regional and global powers must clearly understand the complex dynamics that are driving these coups. This should in theory enable them to respond effectively in ways that strengthen rather than weaken West Africa’s security architecture.

Not equally welcoming of all foreign influences: protesters during the 2023 Niger coup

Mali’s Colonel Assimi Goïta—who has expelled French troops from his country and replaced them with Russian Wagner mercenaries—is struggling to contain a decade-long insurgency in which Islamic militants have taken over large parts of north and central Mali, displacing about 575,000 people. A 12,000-strong UN force, with a limited mandate, has struggled to keep the peace, and is withdrawing its peacekeepers by February 2024, at the request of the military junta in Bamako. There are also reports of the presence of Wagner “guns-for-hire” in neighboring Burkina Faso—led by Captain Ibrahim Traoré—which, like Mali, has similarly halted its military cooperation with France. Traoré has lost half of his country to Islamic jihadists, with two million people displaced. Niger, with a $100 million American drone base and a 1,100-strong U.S. military presence, also continues to suffer from jihadist attacks. The new military regime of General Abdourahamane Tchiani in Niamey further announced the end of defense accords with France, demanding that Paris withdraw its 1,500 troops from among its last Gallic staging posts in the Sahel. Guinea’s Colonel Mamady Doumbouya has, however, largely avoided the scourge of jihadists that are bedeviling his neighbors.

This situation has been complicated by a geopolitical rivalry between France and Russia. French leadership of the Group of Five (G5) Sahel countries since 2013—Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Mauritania, and Chad—has now spectacularly collapsed. Military regimes in Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger, and Guinea have become hostile to Paris, with many protesters across francophone Africa waving Russian flags in opposition to the former colonial power. Russian mercenary group, Wagner, is currently assisting the military regime in Mali to battle militants, which governments in Niger and Burkina Faso are also struggling to contain.

This essay uses the case study of Niger’s putsch of July 2023 to assess the domestic, subregional, and external dimensions of West Africa’s recent insecurity, before making some suggestions on how to strengthen the subregion’s security architecture.

Niger: Of Political Godfathers and Military Brass Hats

The military coup d’état in Niger in July 2023 is a microcosm of West Africa’s security dilemmas. This was the fifth putsch that the country of 26 million people has experienced since its independence from France in 1960. General Abdourahamane Tchiani’s coup thus repeated a historical pattern. Landlocked Niger is among the poorest countries in the world, despite the oil-rich nation being the world’s seventh largest producer of uranium. Both civilian and military governments in Niamey have, however, failed to develop the country, and have often been accused of corruption.

Niger has remained stubbornly stuck at the bottom of human development league tables. But despite widespread claims of the country benefitting from huge sums of aid, it is clear that much of this assistance has not gone towards poverty reduction, but instead disproportionately benefitted foreign interests who tend to channel such assistance through their own citizens and institutions (as well as through international bodies like the UN), selling goods and services produced in their own countries to states like Niger.

President Mahamadou Issoufou held power in Niger for a decade from 2011, before handing over to his protégé: the deposed Mohamed Bazoum. A political godfather, Issoufou unsuccessfully sought to mediate this dispute between his successor and the former head of his presidential guard, General Tchiani. Bazoum had narrowly survived a coup attempt on the eve of his assumption of office in controversial elections in April 2021. His savior at the time was ironically Tchiani, the decade-long head of the 700-strong presidential guard who overthrew him in July 2023. Bazoum had caused discontent within the military by sacking chief of staff, General Salifou Modi, and reportedly preparing to replace Tchiani. The putsch thus appears to have been a pre-emptive strike, with Tchiani able to mobilize support within the military and broader population by exploiting grievances over continuing challenges in battling jihadists across the Niger-Mali-Burkina Faso tri-border area, as well as over the rising cost of living.

Nigeria: Gulliver’s Troubles

It is often said that whenever Nigeria sneezes, West Africa catches a cold. The subregional Gulliver accounts for nearly 70 percent of West Africa’s economy and half of its population. Nigeria is thus a bellwether state for measuring the subregion’s security temperature. Abuja has historically been the pillar around which security has been built in West Africa. Veteran politician, Bola Tinubu, was declared president of Nigeria in May 2023, before subsequently being elected as ECOWAS chair. Led by Abuja, the subregional bloc announced the severance of trade and electricity to Niger after the July 2023 coup, banned flights, froze financial assets, and—without apparently having properly consulted military defense chiefs who met a week later—ineptly gave Niger’s military junta a week to surrender power to Bazoum or face a subregional military intervention. This ill-conceived ultimatum has now come and gone, leaving ECOWAS with egg on its face. In August 2023, ECOWAS leaders contradictorily ordered a subregional force to restore constitutional order in Niger, while simultaneously stressing the need to use peaceful means to achieve this outcome.

Nigeria, under the military dictatorships of Generals Ibrahim Babangida and Sani Abacha, had acted as a regional hegemon in the 1990s, deploying troops to Liberia and Sierra Leone under the ECOWAS Ceasefire Monitoring Group (ECOMOG) in which it provided 80 percent of the troops and 90 percent of the costs. Both peacekeeping missions cost Abuja at least $2 billion, while the country suffered about 1,500 fatalities. Even these two praiseworthy missions, however, represented “hegemony on a shoestring,” eventually requiring UN interventions to stabilize Liberia and Sierra Leone. Nigeria, with its armed militants in the northeast operating with groups across Niger, Cameroon, and Chad, has, however, now metamorphosed from being the bulwark of West Africa’s security to becoming an exporter of insecurity across the Lake Chad basin.

Unlike Babangida and Abacha, President Bola Tinubu needs to contend with parliament and public opinion in launching what would clearly be a deeply unpopular military intervention in Niger. Amidst a $100 billion debt and cost of living crisis triggered by the removal of the country’s fuel subsidy, Nigeria’s ill-equipped and under-funded military is now a shadow of its former self, struggling to pacify Boko Haram and Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) militants in Nigeria’s northeast, as well as to stem attacks by Fulani herdsmen and kidnappers across the country. Abuja has thus massively scaled back its peacekeeping activities, also following the constant breakdown of its armored personnel carriers in the AU/UN peacekeeping mission in Darfur. A Nigerian-led military intervention has been vociferously opposed by the general public, as well as by several Nigerian legislators and religious leaders, with the country sharing a 1,600-kilometer border with Niger, and many Hausa groups—an ethnicity to which General Tchiani belongs—in Nigeria’s Kano and Sokoto states enjoying close family ties and lucrative trading links across the two countries’ common border.

ECOWAS: Subregional Friends and Foes

Given this complicated context, understanding the regional dynamics of this conflict is essential. With ECOWAS threatening to launch a military intervention to restore the deposed president Bazoum to power, one of General Tchiani’s first acts after declaring himself president in July 2023, was to announce a renewal of military cooperation with anti-French military regimes in Mali and Burkina Faso. Bamako and Ouagadougou reciprocated by announcing that they would regard any ECOWAS military intervention in Niger as a “declaration of war” on them, promising to come to Tchiani’s aid, and all three military juntas subsequently signed a tripartite mutual defense pact. The military regime in Guinea has more quietly been supportive of Niger’s putschists.

Amidst these profound subregional divisions in which a quarter of ECOWAS states are now under military rule, the viability of the recently completed Niger-Benin pipeline set to transmit oil to Europe, could be under threat. Chadian leader, Mahamat Idriss Déby, has tried rather unconvincingly to mediate this dispute. But having himself assumed power through a French-backed coup, he continues to commit gross human rights abuses by killing protestors and jailing opponents of his rule. In the Maghreb, Algeria’s military-dominated regime—which has a 1,000-kilometer border with Niger—has publicly cautioned against an ECOWAS intervention, and also offered to mediate.

ECOWAS has been split into four broad camps and is facing an existential crisis. Nigeria as the subregion’s “Limping Leviathan”, has a recently elected president Bola Tinubu, who has so far lacked a sure touch in foreign policy, and has been forced into an embarrassing climbdown from threats of a military intervention. The second group of “hawks” within ECOWAS, which has, like Nigeria, rejected the Niger junta’s proposed three-year transition to civilian rule, include Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal, Ghana, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, and Benin, whose civilian leaders—some with poor governance records—themselves fear coups by their own militaries. Many opposition parties and publics across these countries have, however, condemned any subregional military intervention by ECOWAS. The third group of “muddlers” include Liberia, Sierra Leone, Togo, and Cape Verde, some of which have expressed concerns about the viability of a successful intervention to restore Bazoum to power, with Togo even being accused of collaborating with the military junta in Niamey. A fourth group of military putschists has seen governments in Mali and Burkina Faso (and more quietly Guinea) pledge military support to soldiers in Niger to confront any ECOWAS intervention. The African Union remains ambivalent towards any armed subregional operation. In January 2024, the military regimes of Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso announced their withdrawal from ECOWAS, leaving the subregional body facing its most serious challenge to its five-decade existence.

External Actors

We next turn to examine the three main external actors operating in West Africa’s security architecture: France, America, and Russia. These countries’ interventions have often damaged rather than strengthened subregional security. Françafrique has historically represented a sordid relationship between Paris and its former African colonies involving corrupt political dealings, and secret military agreements that have traditionally kept assorted autocratic clients in power in countries like Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal, Togo, Gabon, Central African Republic (CAR), and Chad. During their military intervention in Mali in January 2013, French troops were sent to guard uranium mines in neighboring Niger. At the time of the Niger coup in July 2023, French soldiers were still protecting uranium mines in northern Niger controlled by the Orano Group which has 17 industrial sites in France. These actions continued an exploitative pattern in which French companies have monopolized economic interests in its former colonies. Before the 2023 putsch in Niger, Paris had kept 1,500 troops and an airbase in the country. French leadership of the G5 Sahel countries subsequently crumbled, having effectively used regional soldiers as cannon-fodder to fight jihadists, while itself adopting a more cautious but domineering approach. Very noticeable in pro-junta street protests in Niger after the 2023 coup—as earlier seen in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Guinea—was the waving of Russian flags, and strong condemnation of the former French colonial power.

When four American soldiers were killed in an October 2017 ambush in Niger, many Americans were wondering what U.S. troops were doing in the country. Twenty-four years earlier, the Bill Clinton administration had crippled UN peacekeeping in Africa after 18 American soldiers were killed in a similar ambush in Somalia (in which over 1,000 Somalis died), resulting in the withdrawal of American troops from the East African country amidst loud cries of “No boots on the ground.” U.S. President George W. Bush’s global “war on terror” from 2001, was enthusiastically continued in Africa by his successor, Barack Obama, who massively expanded America’s military presence, establishing a military footprint in a dozen African countries, while constructing drone bases in Djibouti, Ethiopia, and Seychelles.

The Kenyan-Kansan also initiated the $110 million drone and air base in Niger, which now has 1,100 American troops. Uncle Sam thus, at first, committed himself, after the July 2023 coup in Niamey, to restoring Bazoum to power. The ousted president penned a clearly ghost-written piece in the Washington Post, seeking American assistance to restore his mandate, while unsubtly raising the specter of Russian interventionism through Wagner mercenaries. The U.S.-dominated World Bank subsequently cut off annual aid of $600 million to Niamey, while Washington froze military cooperation with the Niger military. With strong anti-Western sentiment in Niger, a Franco-American backed ECOWAS military intervention would have been widely perceived as a subregional Trojan Horse to protect Paris and Washington’s military and economic interests in Niger.

American policy appears to be in disarray in a country that U.S. Secretary of State, Antony Blinken, had described as a “model of democracy” just six months before the Niger coup. Washington has, however, sensibly avoided the openly hostile French posture towards Niger’s military junta. It must now halt its traditional deference to Paris on Sahel matters to avoid being tarred with the same neo-colonial brush. Uncle Sam should instead strongly back regional mediation efforts by ECOWAS and the AU, bolstered by the UN. Facing a tough re-election battle in 2024, the incumbent President Joe Biden will be keen to avoid another “Somalia-style” military disaster in Niger.

Russia, like China, adopted the majority African position that criticized the 2023 Niger coup, while calling for a return to constitutional order. Its late Wagner chief, Yevgeny Prigozhin—whose mercenaries are supporting the regimes in Mali and the Central African Republic—however welcomed the junta, offering assistance to the putschists in battling what he portrayed as “Western neo-colonialism” in Niger. Prigozhin died in a suspicious plane crash in August 2023, though his mercenaries continue to operate in Mali and CAR. Speculation continues as to whether Niger’s military brass hats will turn to Wagner mercenaries to bolster the country’s counter-insurgency efforts.

Whither Pax West Africana?

ECOWAS leaders held their annual summit in the Nigerian capital of Abuja in December 2023. They agreed to set up a troika of heads of state (Togo, Sierra Leone, and Benin) to mediate with the junta in Niger, before calling for the release of ousted president Mohamed Bazoum, and the progressive easing of ECOWAS sanctions on Niger based on progress by the military junta towards a swift transition to civilian rule. While noting the successful holding of elections in Nigeria, Guinea-Bissau, Sierra Leone, and Liberia in 2023, subregional leaders were brutally honest about the need for “deep reflection” on “actionable recommendations” to improve the transparency and credibility of subregional elections, as well as the need to forge inclusive development and accountable governance. West African leaders further extended the mandate of ECOWAS peacekeeping missions in Guinea-Bissau and Gambia, condemned a November 2023 coup attempt in Sierra Leone, and called for the urgent activation of an ECOWAS Standby Force to undertake counter-terrorism missions across the subregion.

Given continuing instability in the subregion fueled by external actors, strengthening West Africa’s security architecture remains critical. To achieve this, subregional governments must—as they themselves recognized at their recent summit—address the root causes of conflicts, with the international donor community generously supporting genuine democratic reformers in such efforts. Furthermore—building on legendary Ghanaian leader Kwame Nkrumah’s idea of a supranational continental African High Command—an effective 25,000-strong African Standby Force (with a 5,000-strong West African brigade, endorsed again at the recent ECOWAS summit) needs to be urgently operationalized to work alongside the UN, and be funded by the world body through assessed contributions. This would avoid having to create a fire-brigade from scratch each time a local brushfire erupts.

Some studies have noted that in half of conflict cases, countries like Liberia, Mali, and Guinea-Bissau have tended to relapse into war within five years as a result of inadequate peacebuilding. Typically, over 80 percent of funding for UN peacekeeping missions goes directly to support the salaries and other needs of the operations, not to rebuilding war-torn countries. Much more funds therefore must be put into peacebuilding efforts in conflict-afflicted West African countries, while the UN Peacebuilding Commission should be urgently strengthened, as UN Secretary-General, António Guterres, suggested in his July 2023 report entitled “A New Agenda for Peace.”

A strong and revived Nigeria will also be critical for bolstering West Africa’s security architecture. The regional hegemon has conducted seven elections since 1999, and has managed to avoid a return to military rule for the last 24 years. It is important to remember that Nigeria’s first two democratic experiments lasted just five (from 1960 to 1966) and four (from 1979 to 1983) years respectively, while military brass hats have ruled the country for 29 years. The stakes are thus extremely high. With rumors of efforts to derail Nigeria’s electoral process in February/March 2023 and impose a military regime, these are not theoretical concerns that can be taken lightly. As military rule has returned to Mali, Guinea, Burkina Faso, and Niger, it is important that Nigeria sets a good democratic example by keeping its soldiers out of politics.

The challenges of the West African Gulliver are, however, enormous, and will clearly require dynamic leadership: 138 million poverty-stricken citizens, a $100 billion national debt, and 37 percent unemployment, are just part of lackadaisical and languid president Muhammadu Buhari’s difficult legacy (from 2015 to 2023), despite some of his infrastructure-building efforts. His septuagenarian successor, Bola Tinubu—a political godfather who has emerged from the shadows to sit on the throne—is similarly frail, often slurring his speech. Nigeria is clearly no country for old men. But West Africa’s Gulliver appears to be stuck with yet another Lilliputian member of the geriatric “Old Guard.” Could this be the last throw of the dice for contemporaries that Nigeria’s Nobel literature laureate Wole Soyinka once dubbed “The Wasted Generation?”

The Niger coup has glaringly exposed the fragility of many West African governments. As U.S. president John F. Kennedy famously noted in 1962: “Those who make peaceful revolution impossible will make violent revolution inevitable.” Many democratically elected governments across the subregion have traditionally closed off political systems by autocratically clamping down on genuine opposition—what West African civil society activists have often termed “civilian coups d’état”—making the military the only viable alternative for political change. Self-serving soldiers have, however, failed as spectacularly as politicians over the last six decades to transform West African societies. Within ECOWAS itself, current regimes in Senegal, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea-Bissau, Gambia, Togo, and Sierra Leone could all be vulnerable to future coups if democratic governance is not properly practiced. Even the kleptocratic regional Gulliver, Nigeria, must get its own house in order to ensure that the military “Men on Horseback” remain in their barracks.