- Home

- Horizons

- How Russia’s Quest for Influence Made It Embrace Chaos - Moscow’s Strategic Trajectory from Partner to Disruptor

Nikolas K. Gvosdev is Director of the National Security Program at the Foreign Policy Research Institute (FPRI), where he also serves as a Senior Fellow in the Eurasia Program and Editor of FPRI’s quarterly journal of world affairs, Orbis. He is a Professor of National Security Affairs and formerly the Captain Jerome E. Levy Chair in Economic Geography and National Security at the U.S. Naval War College. You may follow him on X @FPRI_Orbis.

Nikolas K. Gvosdev is Director of the National Security Program at the Foreign Policy Research Institute (FPRI), where he also serves as a Senior Fellow in the Eurasia Program and Editor of FPRI’s quarterly journal of world affairs, Orbis. He is a Professor of National Security Affairs and formerly the Captain Jerome E. Levy Chair in Economic Geography and National Security at the U.S. Naval War College. You may follow him on X @FPRI_Orbis.

The flight of Bashar al-Assad to Moscow in December 2024 has brought to a close Vladimir Putin’s second attempt to secure Russia’s position as one of the major powers of the global system. The pressures of maintaining the “special military operation” in Ukraine and the political and generational transitions now underway in Russia are inexorably generating the conditions that will usher in a new and distinct post-Putin Russian approach to international relations.

Over the course of his presidency and prime ministership, Vladimir Putin—and the Russian elite more broadly—has been guided in foreign policy matters by three principal imperatives. The first is that Russia must remain one of the agenda-setting powers of the international system. No one in the Kremlin leadership trusts that an amorphous “international community” somehow guided by a set of impartial “rules” will benevolently and altruistically protect core Russian national interests. As Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov observed in a 2007 speech, Russia’s position “is never guaranteed in an evolving international environment. We can preserve, as well as increase, our achievements only through our active involvement in international affairs.” This means that Russia must be one of those states that defines the global agenda.

This creates the second imperative: Putin and his team are adamant that Russia must have the ability to generate power and project influence beyond its borders in order to shape an international environment favorable to the Kremlin’s priorities. This begins with being able to exercise preponderant influence over an extended Eurasian space using all the tools of statecraft—that Moscow, not Brussels, Washington, or Beijing—should set the political, economic and security agenda of the region. In addition, a consistent demand over the course of Putin’s tenure in office has been that other countries in the region should not become members of Western institutions of which Russia is also not a member. The Kremlin worries about a future where its neighbors end up fully integrated into Euro-Atlantic structures—over which Moscow has no influence or veto—leading to Russia’s own marginalization and a direct threat to the maintenance of the Russian position in Eurasia.

Finally, the last imperative is to ensure that Russia can obtain the necessary resources—both technological and financial—for economic development and modernization. Indeed, as Iikka Korhonen and Heli Simola argue in a 2022 essay for Asian Economic Papers, “despite its aspirations for greater economic self-sufficiency in recent years, Russia still has substantial economic connections to the global economy through international trade and financial markets”—especially for capital goods, electronics, and critical technologies which are vital both for its domestic industries (including energy extraction) as well as its military-industrial complex. Thus, as a 2018 Jamestown Foundation analysis concluded, “Russia’s strategy pursues both a global power objective and a domestic economic objective.”

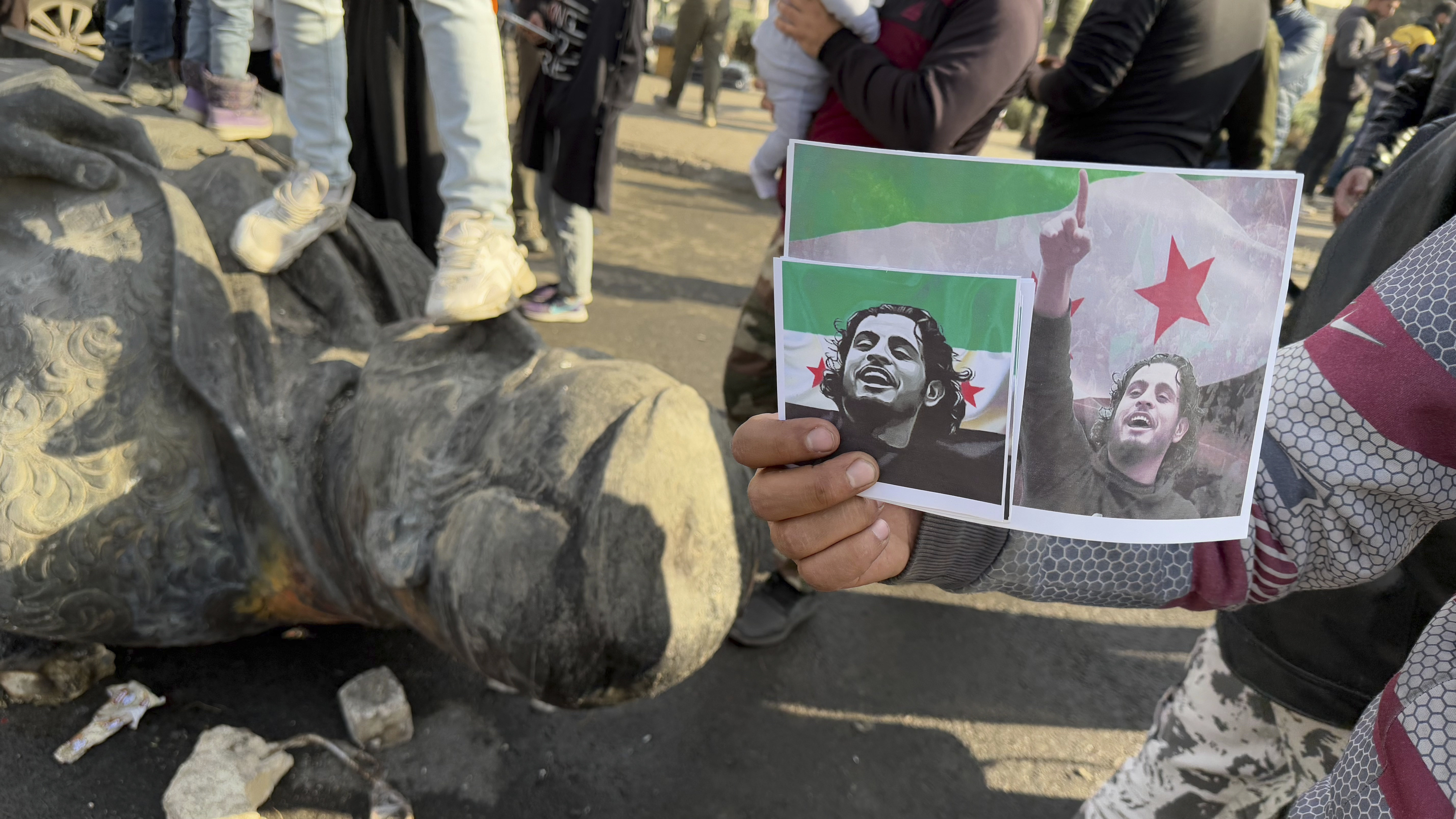

How the tables have turned: government supporters wave Russian flags (left); Syrian opposition supporters stand on the toppled statue of Hafez al-Assad / Source: Guliver Image

Immediately upon taking office as president in 2000, Putin signaled his willingness to work within an American-led concert of great powers—as long as Russia remained one of the countries that would help steer the international system. Putin and his team expected that Russia would be included in a new, twenty-first-century concert of powers to regulate global affairs. Putin’s calculation was that a Russia that demonstrated its willingness and ability to assist Washington in the stabilization of a post-September 11th world would, in turn, lead the United States to recognize Russia’s equities. In other words, by working with the United States, Russia could secure its principal foreign policy objectives and take its position as a vice-chairman of the U.S.-led board of global governance.

Putin expected that partnership with the West would lead to a voluntary cessation of the eastward enlargement of Euro-Atlantic institutions at the Vistula River and the Baltic littoral, with Russia taking the lead in organizing the Eurasian space. A Russian-led Eurasia (via the Eurasian Union and the Collective Security Treaty Organization) would then partner with the EU and NATO to realize the vision of a common space stretching from Vladivostok to Vancouver. However, when it became clear that, in pursuit of partnership with Russia, the West was not prepared to accede to any Russian sphere of influence, Putin’s approach became more controversial—as reflected in his 2007 Munich speech and his 2008 tête-à-tête with then U.S. President George W. Bush in Bucharest—and culminated in the 2008 Russian incursion into Georgia. The attempt to reset U.S.-Russia relations under the presidencies of Barack Obama and Dmitry Medvedev was a last effort to see whether Russian willingness to cooperate with the United States—and the West more broadly—could secure Russia’s foreign policy objectives. However, the Russian political elite came to the conclusion that U.S.-sponsored “rules of the game” for international affairs were increasingly “incompatible with Russia’s vital national interests,” and that the United States was not really interested in any role for Russia in co-managing the international system.

As this process played out, Moscow started its evolution in its foreign policy perspective from working with the West to preserve global stability to providing an alternative approach to world affairs. If the West was not interested in maintaining Russia as a great power to serve as a partner in global governance, the Putin and Medvedev teams began to envision Russia as a “coordinator and mediator between Western and non-Western centers of a multipolar world” where Russia would remain an agenda-setting state—and where the rising powers of the Global South and East would want Moscow to be able to play that role.

This process was aided by two developments. The first was Russia’s own economic and political recovery during the 2000s, which made it more feasible for Russia to move “from a relatively passive refusal to accept Western initiatives… into an activist foreign policy with an ambitious global scope,” as articulated by Julia Gurganus and Eugene Rumer in a 2019 paper for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. The second was the emergence of a major gap between sweeping U.S. pronouncements about reshaping the global order, especially with regards to the Middle East, and the willingness of the United States “to follow-through on its grandiose promises”—especially given the reluctance of any U.S. presidential administration to commit large amounts of U.S. personnel or resources to “end tyranny” or “spread democracy.” Playing on fears of U.S. unreliability and unpredictability created a “propitious external environment” for Russia to offer itself as an alternative to “chip away at the U.S.-led international order.”

The Russian intervention in Syrian affairs, starting with Putin’s efforts to forestall U.S.-led military intervention after the usage of chemical weapons in 2013, to the limited direct military intervention in September 2015 to save the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad from being forcibly overthrown, became the most prominent showcase of this new Russian approach to world affairs. By rejecting the demand of the Obama Administration that “Bashar al-Assad must go,” Putin demonstrated Russia’s reliability and its willingness to stand by its partners and honor its commitments, even in the face of U.S. demands. Having prevented Assad’s defeat, however, the Russians wanted to highlight that, in contrast to the chaos unleashed by the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003—and the subsequent failure of American “large-scale” visions for remaking the Middle East, including the 2011 Libya intervention—Moscow’s efforts could bring stability. Instead of promising transformation, the Russian approach would focus on small-scale, jury-rigged, patchwork compromises between rivals and foes—backed and guaranteed by the judicious application of limited amounts of Russian power. It would be rooted in a nineteenth-century vision of spheres of influence and balances of power. If the United States was not prepared to use its overwhelming preponderance of power to impose a solution, then Russia’s “patchwork of de-escalation zones and spheres of influence” offered to every major power in the region the ability “to salvage some of their position and investment in an eventual end game.” Not only countries like Iran, but America’s Cold War-era allies—like Israel, Turkey, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia—now viewed Moscow as the essential linchpin holding the process in place.

As Russia appeared to succeed in Syria, Moscow attempted to take this model and use it in other parts of the world, from sub-Saharan Africa to East Asia. In particular, this approach also showed possibilities for de-escalating tense situations in Central Asia and the Caucasus—particularly over the Caspian Sea and the Karabakh frozen conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan. Russia promoted its efforts as a way to create interim compromises that could lead to greater stability over the long run.

But Moscow’s interventions—notably in Syria—were not pursued by Putin as a vanity project or altruistic gesture. Rather, the Kremlin hoped that Russia could demonstrate its indispensability in achieving “better results than reliance on American power and intervention.” In turn, the Russian government expected that governments around the world which might otherwise be negatively impacted by the disorder that Russian efforts were helping to keep tamped down—the threat of a regional war spreading and drawing in more countries, the problems associated with mass migration, or the security of critical supply chains—would compensate Moscow.

Beyond validating Russia as a global power, the Russian calculation is that a return to playing a more active role in Middle Eastern affairs can create demand for Russian goods and services, starting with arms and nuclear power plants, and particularly technologies that the United States does not want to provide. The Middle East is critical to Russia’s geo-economic strategy: Turkey is set to become Russia’s replacement for Ukraine as a transit country for energy shipments to Europe, while Russian investments in Iraq and Libya are designed to further Russia’s ability to supply Europe with oil. Meanwhile, Russia wants to create a new north-south route that will connect the Russian heartland with the Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean. Most significantly, Russia has used its new-found influence in the region to thwart the U.S. effort to use Saudi Arabia as a pressure point against the Russian economy. Now, instead of competing against Moscow, Riyadh has actively coordinated with the Russians in an effort to set a stable price “floor” for energy, to help guarantee revenues for both of their treasuries. In addition, given the continued uncertainties that Western sanctions create for European and U.S. financial institutions to consider lending to Russia or facilitating investment, Moscow hopes to continue the trend of securing funds from Middle Eastern sources into its economy.

So, by the beginning of the 2020s, Moscow believed it had found a formula to retain its great power position. Yet as the crisis over Ukraine heated up—with the interim cease-fire arrangements after the 2014-2015 annexation of Crimea and forcible separation of parts of Southeastern Ukraine from Kyiv’s control unable to pave the way for a permanent settlement—Putin discovered the limits of Russia’s indispensability. Russia’s demands for a recession of Euro-Atlantic influence in Eastern Europe were rejected, and Putin decided to use military force to try and create new facts on the ground.

Russia’s “special military operation” in Ukraine has fundamentally changed Russia’s approach to the world. A key part of its strategy in places like Syria has been compromised as Russia’s ability to sustain its operations and projection of power has been depleted by the demands of a difficult and challenging campaign in Ukraine. After 2022, the jury-rigged arrangements, especially in Syria, began to buckle. In turn, this created new facts on the ground. By 2024, Assad was quietly reaching out to his former regional foes—and even the United States—to explore new options. Russia’s growing weakness also accelerated the entropy within the Syrian armed forces as Moscow’s ability to prop up Assad began to be questioned.

For countries like Turkey and Syria, the acceptance of the Russian role was predicated on power relations circa 2019—a condition increasingly non-operative after 2022 and certainly in the aftermath of the October 7th, 2023 Hamas attacks against Israel. Moscow could not sustain its delicate balancing act between Iran and its proxies and Israel; between the Syrian government and opposition groups backed by Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and the Gulf emirates, and ultimately even the United States. Russia was now increasingly becoming dependent both on Saudi Arabia to maintain the OPEC Plus arrangements and on Turkey to serve as one of the most critical “roundabouts” for circumventing Western sanctions.

The extent to which key European and East Asian powers have sanctioned Russia challenged the assumptions that these countries would never risk their equities in their relationship with Moscow (starting with the supply of energy and commodities, and to maintain Russia as that hedge against both U.S. unpredictability and fears of a Chinese diktat). Moreover, the rising powers of the Global South are assessing the extent to which they need Russia to facilitate their own ascendancy as Russia faces further setbacks. Moscow has thus begun to reconsider the value of continuing to play a role—even a limited one—of contributor to international stability, especially if the beneficiaries of those efforts were not willing to support and compensate Russia in its “time of need.”

One might conclude that the collapse of the Assad government—Bashar al-Assad ultimately did comply with Obama’s injunction to leave, albeit some 12 years later—represents a crisis for Russia. But, paradoxically, the recession of Russian power represents the start of a new approach.

The first two iterations of Russia’s role in the world—Putin’s efforts to cooperate with the West, and then to provide an alternative to the United States—were based on the calculation that a Russia that played a role in promoting global stability could secure its own national interests. The emerging and as yet unclear third phase, however, seems to have a very different starting point. Rather than Russia working to help stabilize hot spots around the world—and be compensated for it—the new approach seems to be to let disorder reign. A renewed period of chaos might work to Moscow’s advantage. If for the first 25 years of the Putin era, Russia sought to promote its membership in a concert of great powers—first seeking recognition from the West, then trying to create an alternate concert with the rising powers of the Global South and East—it may now be more willing to stand by and let chaos disrupt the global system. In other words, to wash its hands of efforts to bring stability to different hotspots around the world.

Under the old Syria model, and in pursuit of its larger Persian Gulf strategy that Russia announced in 2019, Moscow might have tried to broker a deconfliction arrangement in Yemen that would guarantee the freedom of maritime movement in the Red Sea. In contrast, the effective Houthi blockade has created real problems for the global economy more broadly and the European economy in particular. That, in turn, makes it more difficult for Europe to completely disconnect from Russian energy while raising energy costs that contribute to economic difficulties (which over time may complicate sustained European support for Ukraine). More disorder in more parts of the world creates the “Eurasian simultaneity” dilemma for Washington, where multiple simultaneous crises stretch thin American resources and attention. A more chaotic international system also creates problems for other states that might seek to constrain, limit or pressure Russia.

Unsurprisingly, in its annual report identifying the most acute risks facing the world, Eurasia Group sees trends towards a G-Zero reality in 2025, an “endemic geopolitical instability that will weaken the world’s security and economic architecture, create new and expanding power vacuums, embolden rogue actors and increase the likelihood of accidents, miscalculations, and conflict.” It explicitly concludes that “No other country in the world is doing more to directly subvert the global order than Russia” and that “its efforts will intensify.”

The next generation of the Russian political elite is grappling with an assessment that there will be no place for Russia within the decisionmaking institutions of the Western world, and that the West seeks to isolate Russia from the main pathways of the current global system to constrain Russia’s economic, political, and military power. If that is the case, then Moscow has nothing to lose by washing its hands of its efforts to bring short-term stability to different troubled regions of the world and letting the rest of the world absorb the costs of disorder and disruption. The Kremlin understands that this will introduce a much greater degree of turbulence in its foreign relations and that outcomes may be suboptimal—but that in a more fractured, chaotic world, Russia has a better chance of forging a series of transactional relationships with key powers of the Global South that can ensure Moscow retains a significant degree of strategic autonomy in a mid-twenty-first century that will likely be dominated by the United States (and its allies) on one hand and China on the other.