Alicia Bárcena is Executive Secretary of the UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). You may follow her on Twitter @aliciabarcena.

Alicia Bárcena is Executive Secretary of the UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). You may follow her on Twitter @aliciabarcena.

The year 2015 witnessed the adoption of three landmark global agreements that set forth a transformational vision of sustainable development for the future. In the framework of the United Nations, and in a context of renewed impetus for multilateralism, countries endorsed the Addis Ababa Action Agenda of the Third International Conference on Financing for Development in July 2015, recasting development financing. Then, in September 2015, the world came together to adopt the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Lastly, just a few months later, a breakthrough was reached on climate change in Paris at the twenty-first session of the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP21).

These three multilateral agreements share a common track and root: the demand that emerged in the 1990s, under the leadership of the UN, for more sustainable patterns of growth and development. Each one has followed its own dynamics and now faces different but complementary dilemmas. For instance, the Financing for Development track is caught in the debate over whether it relies on traditional public and concessional financing or on a new enabling environment with innovative means of financing that include more coordination among governments and greater involvement of the private sector.

The global agreements reached in 2015 may not be perfect, but they represent the culmination of a process initiated by the United Nations in the 1990s that lays unprecedented foundations for the adoption of sustainable development pathways integrating the economic, social, and environmental dimensions. They have left behind the traditional trade-off approach, consisting of what one commentator defined as “growing and accumulating first, then seeking environmentally sustainable growth with equality.”

Instead, the three adopted sustainable development pathways have overcome this false dilemma and now clearly integrate the economic, social, and environmental spheres of development within a universal approach, aiming to “leave no one behind.” These three agreements call for the eradication of extreme poverty and greater equality in our societies; the promotion of inclusive growth with increased productivity and decent work; the mobilization of traditional and innovative financing from public and private actors; and the progressive decarbonization of production, consumption, and urbanization patterns—all under principles of intergenerational solidarity and common but differentiated responsibilities among countries.

As we enter 2016, leaders and decisionmakers from governments, the private sector, and civil society must now come together and turn this vision into reality by shifting into “implementation mode” in order to meet these objectives and achieve the global goals, with the year 2030 as their horizon.

Alicia Bárcena being sworn in as head of ECLAC / Photo: United Nations

For the countries of Latin America and the Caribbean, whose social and economic development is still hampered by historical structural gaps, this implies addressing major challenges of adjusting to unfolding global paradigm shifts, on the one hand, and tackling a complex growth and trade outlook, while avoiding the stagnation of social progress, on the other.

A Dampened Economic Recovery

Global growth has still not recovered from the effects of the economic and financial crisis of 2008–2009. Developed countries show a mixed economic performance: while the recent increase in the federal funds rate in the United States signals the return to more normal conditions, the Eurozone is still struggling to avoid deflation. The emerging and developing economies—China, in particular—show clear signs of a slowdown. Also, although current account imbalances have eased since the first decade of the 2000s, some countries are still running large surpluses that act as a drag on aggregate demand growth—which is badly needed to boost the world economy.

Moreover, global trade flows have lost momentum, slowing to levels below GDP growth. This is a result of the difficult global macroeconomic situation, weak global demand, and structural changes in global patterns of production and trade. They are now well below the average levels of the period spanning from the end of World War II to the global economic crisis that broke out in 2008–2009, during which export volumes grew more than world GDP.

The main factors boosting world trade over this period included the creation of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1947, the establishment of the European Economic Community—the predecessor to the European Union—in 1957 and its successive enlargements, the opening of the Chinese economy, from the late 1970s onwards, and the expansion of global value chains from the mid-1980s.

In contrast, the main factors behind the current low levels include global excess capacity in various industries, the decoupling of financial from real activity, high levels of public debt in several leading economies, a marked worsening of income distribution in most regions, and the recent slowdown in the Chinese economy, coupled with uncertainty about its ongoing rebalancing.

The rapid fragmentation of production that was a strong driver of world trade—especially for intermediate goods—now appears to have reached maturity. The new configuration could result in shorter value chains. For example, China has been substituting imported inputs with local ones in several industries.

Moreover, a shift in aggregate demand towards less import-intensive components has also had a negative impact on trade. On the financial side, efforts to enhance regulation remain insufficient, whilst financial volatility remains significant; these, along with dampened demand conditions and the absence of coordination, are helping to fuel a climate of greater uncertainty.

Regional Weaknesses Exposed

Within this context, the Latin American and Caribbean countries are encountering significant difficulties in increasing exports, output, and investment. In particular, the economies whose production and export structures are anchored in natural resources are experiencing a slowdown in output and employment, as well as significant challenges in tackling their current situation through countercyclical policies. In fact, the mounting deficits and, in some cases, increased debt levels, as well as the consequent reduction of fiscal space, have limited the scope for using public spending as a countercyclical instrument. These have forced the adoption of tighter monetary policies.

As noted previously, the weakness of global aggregate demand has negative implications for a region whose growth has historically been limited by external constraints that have led to stop-and-go situations and frequent foreign-exchange and external debt crises. A production and export structure—concentrated in low-productivity sectors—concerned with a lack of technological dynamism, means that the region remains highly vulnerable to the vagaries of international demand. After temporary relief during the recent commodity supercycle, the weakness of the region’s export structure is now again apparent.

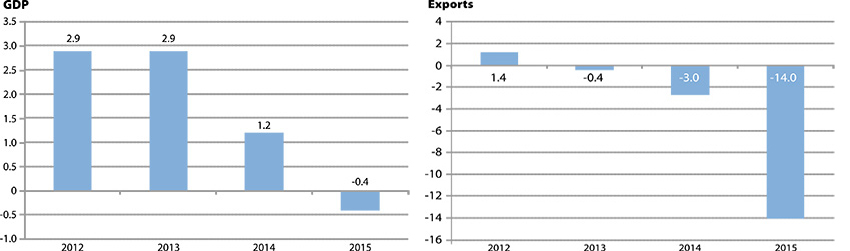

Against this backdrop, the UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) has estimated that the region’s economies contracted collectively by 0.4 percent in 2015 and will grow by just 0.2 percent in 2016, while the value of the region’s goods exports dropped by 14 percent in 2015.

This has been the third consecutive year of falling export value, making 2013–2015 the worst three-year stretch for the region’s exports since the Great Depression. The export contraction in 2015 reflects a sharp drop in prices (-15 percent) that was not offset by a less than 1 percent increase in the volume exported.

Meanwhile, the region’s imports are projected to drop 10 percent in value—also their third consecutive year of decline. The performance of both total exports and intraregional exports was negative, especially in South America, owing to its heavy commodity dependence and weak economic growth in 2015 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Latin America and the Caribbean: annual variation in GDP and merchandise export value, 2012–2015 (percentages)

Source: ECLAC

Financing for Development

In terms of financing for development, meeting the SDGs will require not only an unprecedented mobilization of resources, but also a reassessment of the way in which resources are obtained, organized, and allocated.

A first important issue is how to foster the mobilization of domestic resources, which is the single most important source of funding for development. Yet in vast parts of our world, it is highly constrained by insufficient revenues, tax evasion and elusion, and illicit flows.

In the particular case of Latin America and the Caribbean—notwithstanding the fact that tax reforms undertaken in the region in the past two decades have modestly increased the tax burden and shifted fiscal policy towards improving redistribution—tax evasion remains very high by international standards (the rate of VAT evasion is between 17.8 and 37 percent of total revenue in the region, whereas it reaches between 10 and 22 percent in OECD countries).

In addition, governments are facing new challenges, including illicit flows, which account for a massive outflow of financial resources from developing economies. In Latin America and the Caribbean, illicit outflows surpass FDI flows, while representing twice the amount of remittances and 15 times the amount of official development assistance (ODA) received by the region. Thus international cooperation in fiscal matters becomes a key issue to overcome the challenges of domestic resource mobilization. International and regional agreements should be the basis for common international tax rules and standards to improve transparency, as well as prevent the erosion of tax bases.

A second fundamental concern stems from the recognition that public flows, including traditional development flows such as ODA, will simply be insufficient to meet the demands of the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. They must be complemented with private flows, which constitute the bulk of external financing for middle-income countries (MICs), as emphasized by ECLAC in our March 2015 report entitled Financing for Development in Latin America and the Caribbean: A Strategic Analysis from a Middle-income Country Perspective.

The fact that private capital is driven by profit rather than developmental concerns can lead to underinvestment in areas that are crucial for development if the expected return—on a risk-adjusted basis—underperforms. The challenge is to mobilize private resources and blend private and public resources in order to achieve the leverage required to maximize the impact for development financing. Since private flows respond to market incentives, appropriate incentives and public policies are needed at both the national and global levels in order to define the role of public and private flows and their different levels of interaction.

A third challenge is the fact that mobilizing an adequate volume of combined public and private funds is made more complex by the significant changes to the development financing landscape in recent decades. While these changes increase the options of funding for development, they also increase the complexity of coordinating and combining the variety of actors, funds, mechanisms, and instruments under a coherent development financing architecture.

Additionally, while national policies must play a key role in a renewed financing for development architecture, they are a necessary, but not a sufficient, condition to make this architecture effective in responding to countries’ development needs. An enabling external environment must address the asymmetries in the international financial architecture and reflect, in its institutional structure, the shift in global economic and political power towards developing countries and MICs. It must also point out the inconsistency between the importance of developing economies and their share in world trade, and enhance their opportunities for market access, technology transfer, and knowledge acquisition.

The scale and role of foreign direct investment (FDI) must also be put into perspective. FDI should complement domestic capital, given its substantial impact on the domestic economy. The majority of investment in Latin America and the Caribbean is local, and the ratio of FDI inflows to gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) is approximately 20 percent in most countries. While the two magnitudes are not exactly comparable (FDI includes cross-border mergers and acquisitions, which are not included in GFCF), this ratio gives a rough estimation of the weight that FDI has over total investment.

But FDI is not free: as stocks of FDI have grown across the region, the profits that transnational corporations make have also grown, with a great impact on the current account deficits that have expanded in the past five years. Countries should target the types of FDI that can boost their productive capacity and contribute to structural change in their economies towards more knowledge-intensive sectors.

Being Left Out?

Among the unfolding global paradigm shifts, the “fourth industrial revolution”—which includes the current digital revolution—is transforming the production, trade, and distribution of goods and services. It is also affecting all economic and social activities, with significant impacts on human capabilities, skills, and labor markets.

Production will be increasingly concentrated in a few large enterprises with a global presence, while markets will become increasingly fragmented. Among the drivers of increased concentration are economies of scale obtained from the operation of large data centers, network effects and technological progress in robotics, and the application of the digital economy to ever more sectors. This reduces the wage component in costs and thus tends to bring production activities back to more developed countries.

Meanwhile, increased fragmentation is brought about by the personalization of products, services, and content, which generates niche markets in which economies of scale lose their relevance. This latter trend could spread out the production of goods and services geographically, thereby opening up opportunities for countries distant from the technological frontier, as well as for small and medium-sized enterprises.

Regarding climate change and the green economy, the terms of the Paris Agreement have sent a strategic message that the world has to make a critical longterm structural change towards environmental sustainability. Governments must now provide powerful incentives for public and private actors to become key driving forces in generating cleaner patterns of production and consumption, given that research and development for the new low-carbon economy is expected to come largely from the private sector, in close coordination with governments, academia, and research centers.

Moreover, urban development in Latin America and the Caribbean—as the most urbanized region in the world, with over 80 percent of its population living in cities—could offer new opportunities in areas such as smart urban public transport and traffic management, solid waste and waste-water treatment, and low-carbon and low-energy buildings. It could thus enable the region to tap into the digital, technological, and data revolutions. Greening the economy through lower-carbon production systems in industry, improved energy management, enhanced spatial location, lighter vehicles, and a “big push” for the development of renewable energies—such as solar and wind power—enshrines huge potential, including at the transnational level.

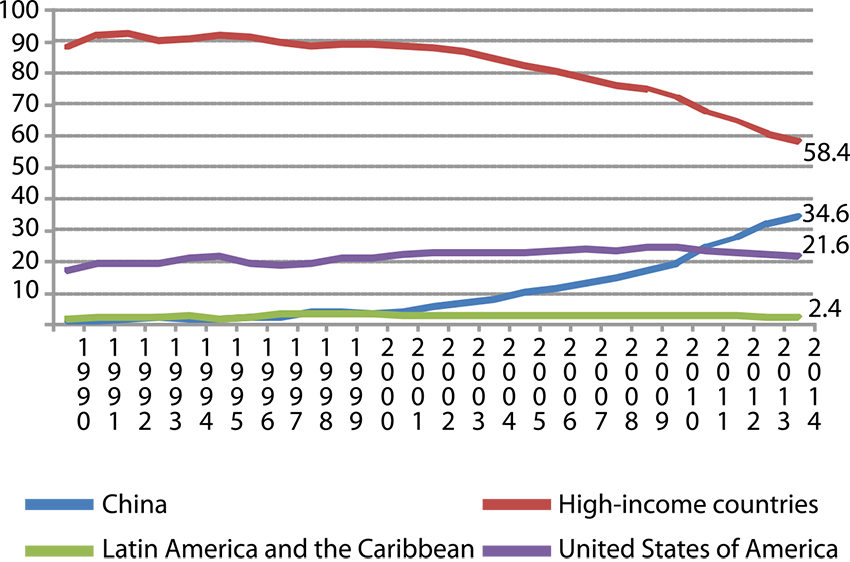

However, this will not be possible unless the countries develop the capabilities for the new technological and environmental paradigm, such as data centers, broadband networks, and, especially, a skilled workforce. But the Latin American and Caribbean region still has a long way to go to become an innovation-driven region (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Latin America and the Caribbean: share of total patent applications, 1990–2014 (percentages) / Source: ECLAC, on the basis of information from the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO).

Since the creation of more advanced technology basically occurs outside the region, Latin America and the Caribbean will need structural changes in tune with the current industrial revolution in order to catch up. Growth and employment will depend on the level of integration with the global digital economy, which requires the development of a digital ecosystem, improved infrastructure, human capital, and a better business environment. The definition of global standards, regulation of data flows, intellectual property rights, security, and privacy are critical elements for creating a single Latin American digital market.

Against this backdrop, the ongoing global paradigm shift calls for a fundamental rethinking of relations between governments, the private sector, civil society, and multilateral organizations. These shifts include the unaddressed challenges stemming from the economic and financial crisis of 2008; the reconfiguration of economic, trade, and manufacturing relations (including the emergence of new mega-regional trends); the rapidly unfolding knowledge, technological, and data revolutions; and the new social demands of empowered citizenship.

Regional Economic and Technological Integration

The Latin American and Caribbean region is facing its bleakest international economic outlook since 2009. The entrenching of its natural resource specialization and its persistently low-tech production structure with environmental externalities are making it hard for the region to find a way out. Although some traction could be gained from the nominal depreciation of several countries’ currencies, this effect is limited by a narrow export basket.

The region must also deepen its economic and technological integration. A common bloc with a uniform normative and institutional framework would significantly support regional efforts to expand the digital economy, which covers diverse areas—from telecommunications infrastructure (fixed and mobile broadband networks) to information and communications technology industries (hardware, software, and ICT services), including the appropriation of those technologies by users. In our 2015 document The New Digital Revolution: From the Consumer Internet to the Industrial Internet, ECLAC proposes moving towards a regional digital single market, which will allow taking advantage of network and scale economies to compete in a world of global platforms.

Progressing towards an integrated space with common rules is vital to promoting production linkages, strengthening intraregional trade, and supporting environmentally sustainable production and export diversification. Despite the shrinking fiscal space, the region must take bolder strides in designing and implementing smart industrial and technology policies in order to diversify and increase productivity. Such policies are crucial to raising the region’s longterm growth potential and improving its sustainable development prospects.