Bret Stephens is an Op-ed columnist for The New York Times. He won the Pulitzer Prize for commentary in 2013 and is the author of America In Retreat: The New Isolationism and the Coming Global Disorder (2014).

There have been periods in history when the great challenge facing America has been to define its relationship with the world: the arguments between isolationists and internationalists on the eve of World War II come to mind. There have also been periods, such as the racial and generational struggles of the 1960s, when the great challenge for America has been to define its relationship with itself.

This year, America faces both challenges at once.

As I write, in September 2020, the United States has the feel of a country coming apart. That’s not an easy sentence to write—because of what it implies; because it could still be avoided; and because it would have seemed preposterous just a few months ago. Yet, ever since the horrific killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer on 25 May 2020, nearly every day has brought new scenes of urban unrest: a mixture of political fury and ordinary lawlessness that seem to connect like lightning and deadwood. And nobody in the political fray, right-wing or left-, seems to have any interest in either cooling off or backing down.

The scenario now likeliest to bring America to grief would begin on election night, with Donald Trump seizing on early results to declare himself the victor, even as mail-in ballots—which in recent years have leaned Democratic and which Trump has insisted are vulnerable to fraud—have yet to be counted (the reason is rooted in state legislation that prohibit counting mail-in ballots prior to election day, irrespective of when they are received).

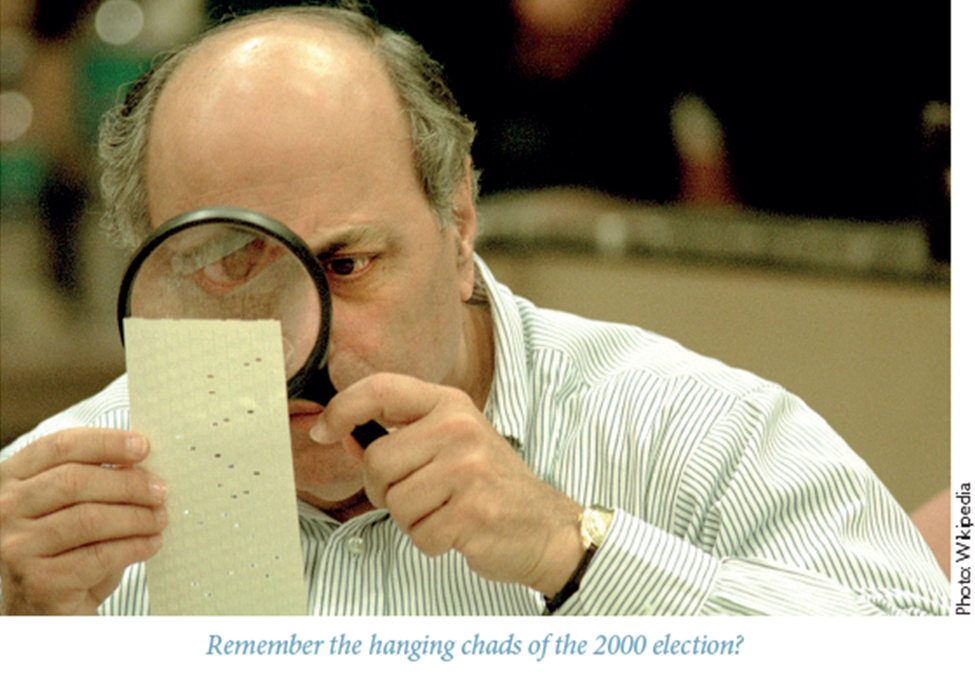

Next, the election could become mired in lawsuits reminiscent of the Florida recount contest in 2000, this time in a half-dozen states with sharply polarized and evenly divided electorates. Courtroom battles might then attract massive protests and counter-protests—which could quickly break out in brawls and shootings. Police might shoot and get shot. Should the police’s civilian masters fail to back them, many might go on silent strikes and refuse to maintain public order. Neighborhood vigilante groups would spring up in hundreds of neighborhoods to maintain security. Trump could declare a national emergency to federalize the National Guard, while Democratic state governors could respond by rejecting this Trumpian declaration and assuming command of their own National Guards.

And on to the catastrophic denouement: Trump might call upon the military to intervene. Some generals would follow the president, but others might not. His opponent, Joe Biden, could declare victory as the United States hurtles toward an inauguration day in which two bitter rivals claim the right to take the oath of office.

I do not offer this scenario because I am fully confident that it will come to pass: political prediction is still a lousy science. But the fact that the scenario is even plausible tells us that something has gone terribly wrong in the United States. Diagnosing the disease must begin with the recognition that, whatever else one might say about him, Donald Trump is not so much a cause as he is a symptom.

The question is: a symptom of what?

Crisis of Legitimacies

The answer, in the broadest sense, is a crisis of legitimacy—or perhaps “legitimacies,” plural, is more accurate. It is a broad crisis. What follows is a partial enumeration of the elements of these crises.

The left questions the legitimacy of police departments, with calls to defund the police gaining traction nationwide. The right questions the legitimacy of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, claiming that the FBI used the mechanisms of the “deep state” to organize a conspiracy to bring down an elected president. The left questions the legitimacy of domestic capitalism, with widespread calls to “cancel billionaires” while democratic socialism becomes a surging ideological force. The right questions the legitimacy of global capitalism, which it derides as “globalism” and opposes by way of protectionist trade policies. The left is increasingly hostile to the principle of free speech, seeking to cancel appearances—and careers—of writers or speakers it deems offensive. The right is increasingly hostile to much of the news media, which Trump has described as “an enemy of the American people.” The left believes that Republicans intend to steal the election by means of voter suppression. The right believes that Democrats intend to steal the election by means of mail fraud. The left questions the legitimacy of America’s founding fathers, seeing them not simply as flawed but inspiring creatures of their time, but as inveterate white supremacists who should be knocked, often quite literally, off their pedestals. The right questions the legitimacy of the open society, including a repudiation of America’s traditions of welcoming immigrants and hostility to Constitutional principles such as the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of birthright citizenship.

At the most fundamental level, the left questions the legitimacy of the right in and of itself, and the right questions the legitimacy of the left in and of itself. Each camp sees the other not just as an opponent but an enemy, and not just as an enemy but as a mortal one. This is the delegitimization of the idea that alternations in power are essential for a healthy politics, not fatal to it. It’s the delegitimization of the democratic idea itself.

Such delegitimizations did not come about overnight, or even over the last four years. Nor did they stem from quarrels with the status quo that are themselves illegitimate. There is always “a great deal of ruin in a nation,” as Adam Smith famously observed, and that’s as true in the United States today as it has been at most other junctures in history. Many police departments do need reform; the FBI did not honor its own rulebook when it launched its investigation of the Trump campaign; there are dangerous wealth disparities. And so on.

But there are four significant differences between today’s discontents and past ones. The first is the growing appetite for destruction: significant social and political movements on both the right and left no longer seek to reform the traditional institutions of American life. Instead, they seek to eliminate them, usually without any clear idea of what ought to replace them. The second is that the things at risk of being destroyed are the very things that typically keep healthy societies together—the ties of history, citizenship, law, culture, enterprise, place, obligation, ideals, epistemology, and even the sheer entropy of our daily routines. The third is that all of these stresses are occurring simultaneously. And the fourth is that they are occurring simultaneously in the midst of a once-in-a-century pandemic, raw racial unrest, and the most severe economic crisis in over a generation.

Implausible Scenarios

And so the United States moves toward an election that, should the result be close and contested, could prove catastrophic.

Still, let’s assume that the margin of victory for either Trump or Biden is sufficiently wide as to leave no doubt about the legitimacy of the outcome, and the next inauguration takes place in relative peace. What happens then?

One scenario: a decisive Biden victory leads to a cooling of political temperatures. Biden sets a moderate, inclusive tone for his administration, gently but clearly distancing himself from the Democratic Party’s radical fringe. A chastened Republican Party comes to terms with the blunder it made in embracing a reckless nationalist as its standard bearer and finds its way back to a better version of itself: Reaganesque in its optimism, Eisenhowerian in its prudence, Lincolnian in its commitment to the country’s founding ideals of equality and opportunity. The pandemic is overcome; racial tensions ease; life and politics return to more normal versions of themselves.

Another scenario: a come-from-behind Trump victory brings the left to grips with the realization that Trump is not an illegitimate president, and that efforts to destroy his administration through endless investigations are a fool’s errand. The left also comes to see the damage it has done itself by adopting an aggressive form of identity politics and political correctness that rubs many Americans wrong. Trump mellows his tone somewhat, the country recovers economically, and the country moves along.

Both scenarios, however, are implausible. An overwhelming Biden victory may chasten some Republicans about the perils of aligning their party behind a populist demagogue. But other Republicans will argue that Trump’s real mistake was that he didn’t go far enough, meaning the party should steer even further to the right. A Biden victory, particularly if accompanied by Democratic majorities in both houses of the U.S. Congress, could also lead to sweeping progressive legislation (e.g., the Green New Deal, Medicare-For-All) that would further alienate Republicans and polarize the nation.

As for the prospect of a Trump victory, large segments of the Democratic base will not accept it as legitimate under nearly any circumstances. The “resistance” will protest in huge numbers in the weeks following the election, and some of the protests may descend into violent rioting and looting. Trump will not be magnanimous in victory; he will raise the political temperature with his tweets and pursue a legislative agenda that will almost surely enrage the left.

In short, regardless of who wins in November, it is difficult to imagine a meaningful change in the course of American politics. Something else will have to happen. But what, exactly? And how?

Reclaiming the Center

The answer to the first question is that, somehow, Americans will have to find their way back to a set of once-cherished understandings about our national identity. The broad outlines of this understanding of national identity can be sketched out in the following manner.

The United States is a country in which our goals matter more than our origins. We cherish our personal liberty above the claims of ethnic, racial or tribal belonging. We welcome immigrants from all corners of the globe provided they live within the law and adopt our democratic values as their own. We honor our imperfect founders for championing ideals that were radical in their time and true for all time. Our pursuit of individual happiness does not blur our concern for social fairness. Our exceptionalism as a nation lies in the fact that we are not a nation, as nations are traditionally understood. We pursue prosperity not only for its own sake, but also so that we may be generous with it. We believe in equality of opportunity not outcome. Our differences don’t erase a shared sense of citizenship and an overarching sense of common destiny. We reward initiative and excellence, while also taking care of those who suffer tragedy and loss. We are a land of second chances. We see America in all of its failings and flaws and excesses and shortcomings—and care for it as the last best hope of earth.

In short, we believe, as Bill Clinton put it in his first inaugural, that “there is nothing wrong in America that can’t be cured by what is right in America.”

These understandings used to be commonplaces. Today the feel antiquated. The cultural and political shift that has overtaken much of the United States in recent years—captured in the archly dismissive Millennial line, “Ok, Boomer!”—is arguably no less sweeping than the shift that took place in the late 1960s, though it lacks much of the patriotic idealism and sheer courage of the civil-rights movement. Millions of younger Americans in particular have come to think of the United States as a country saturated by racism, run by a demagogue who is in turn controlled by a foreign power, founded by hypocrites, and benefiting the few at the expense of the many.

A second Trump term is almost certain to further entrench this view. A Biden Administration could do better and would enter office on a wave of relief at Trump’s departure. But it would face skepticism on the far left and entrenched, bitter, and probably ugly hostility on the right.

That is when America will come to its decisive crossroads—when a President Biden will have to make the choice between governing in the moderate and conciliatory vein in which he has campaigned, or in the increasingly leftist vein of the party to which he belongs. Biden has more than once described himself as a “transitional” figure, in reference to his age and the likelihood that, if elected, he will be a one-term president. But he has been vague on the question of what he thinks he should be a transition to: a new era of ambitious (and costly and controversial) government-led change, or the restoration of conventional governance, with at least occasional bipartisan legislative successes.

The political temptation for Biden will be to move left. Democrats will want not only to undo the legacy of Trump’s tax cuts and deregulatory agenda, but also to underwrite a massive expansion of Medicare and an ambitious climate agenda. If achieving this requires an end to the Senate filibuster, they will want to do that as well, even as they know it might cost them dearly once Republicans control the White House and Senate.

But the more meaningful opportunity for Biden—which ought to tempt him all the more if he can govern for history’s sake, rather than for the sake of re-election—will be to reclaim the political center, and to do so in a manner that allows the country to rediscover its own center once again. As a matter of politics, he can set a tone by appointing Republicans to his cabinet, not just those who supported him, like former Ohio Gov. John Kasich, but even—perhaps especially—those who currently oppose him. As a matter of domestic policy, he can pursue viable bipartisan immigration reform, trading increased border security for a viable path to citizenship for undocumented workers. As a matter of foreign policy, he can craft a bipartisan security doctrine that takes the threats of Russian irredentism and Chinese expansionism seriously and seeks to counter it by forceful diplomatic, economic, and, if necessary, military means.

But the largest opportunity for Biden is neither a matter of politics nor policy, but rather one of pedagogy. In the spirit of presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and John F. Kennedy, Biden needs to remind ordinary Americans of why patriotism matters and how it should be practiced—not boastfully but purposively; not selfishly but generously; not un-self-critically but with a view toward national repair and renewal.

It is one of the oddities of American life that we simultaneously venerate great political oratory while treating it as superfluous at best to the core task of governance. In fact, the two are intimately linked: great oratory is how nations give meaning to their past and purpose to their future. Such oratory needs to be connected to a new emphasis on civic education and greater opportunities for public service, civil as well as military. A Biden Administration that inaugurated a twenty-first century version of the Civilian Conservation Corps with a focus on environmental stewardship, or that created opportunities for short-term military service (including for those past the age of military service), would leave a national imprint that would last far longer than a four-year presidential term.

Restoring Social Trust

All this may seem far afield from America’s immediate crises. What, after all, does great patriotic oratory or robust civic education have to do with ending a pandemic, reducing unemployment, or easing racial tensions? My answer is that it is essential to their resolution, because no nation can address any challenge without social trust.

A Biden presidency will succeed or fail based on that criterion alone. The question can be formulated this way: will it lead to increased levels of social trust that allow a diverse set of political actors and movements to behave somewhat more cooperatively? Or will it be yet another centrifugal force in American politics, leading to ever-greater levels of social distrust and animosity?

What goes in America’s domestic politics goes also for its relations with, and position in, the wider world. Although the Trump Administration has had occasional successes abroad—brokering peace between Israel and both Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates being the most obvious example—its most notable contribution to American diplomacy has been to discredit the idea that the United States deserves its place as the world’s premier power because of the inherent attractiveness of its ideals and the decency of its purposes. The Ugly American has been much spoken about in the past, but in the administration of Donald Trump he has definitively arrived.

A Biden presidency alone will not repair the breach that the Trump presidency has created between America and the world. Though it’s rarely commented on today, the Obama Administration also did its part in alienating longstanding allies (particularly in the Middle East) and undermining confidence in American security guarantees (particularly in eastern Europe).

But Biden needn’t be beholden to Obama’s cramped vision of American foreign policy. It is possible to match realism about the necessity of American power in a world of near-peer competitors with renewed idealism about the purposes of that power. Such idealism can, in turn, restore global faith in American leadership, at least when it’s accompanied by habits of close consultation, fair dealing, burden sharing, and shared faith in liberal-democratic ideals.

Today, in an era of waning confidence in democratic institutions and open societies, rising populism and public misinformation, and revisionist regimes with revanchist aspirations, American leadership, steadiness, and self-confidence have never been more necessary. But as it was proverbial 2,000 years ago, so it remains today: “Physician, heal thyself.” For the United States to again find its footing in an uncertain world, it must first find a way to restore its shaken faith in itself.