Zachary Karabell is an author, commentator, and investor as well as the founder of the Progress Network. His next book, Inside Money: Brown Brothers Harriman and the American Way of Power, will be published in May 2021. You may follow him on Twitter @zacharykarabell.

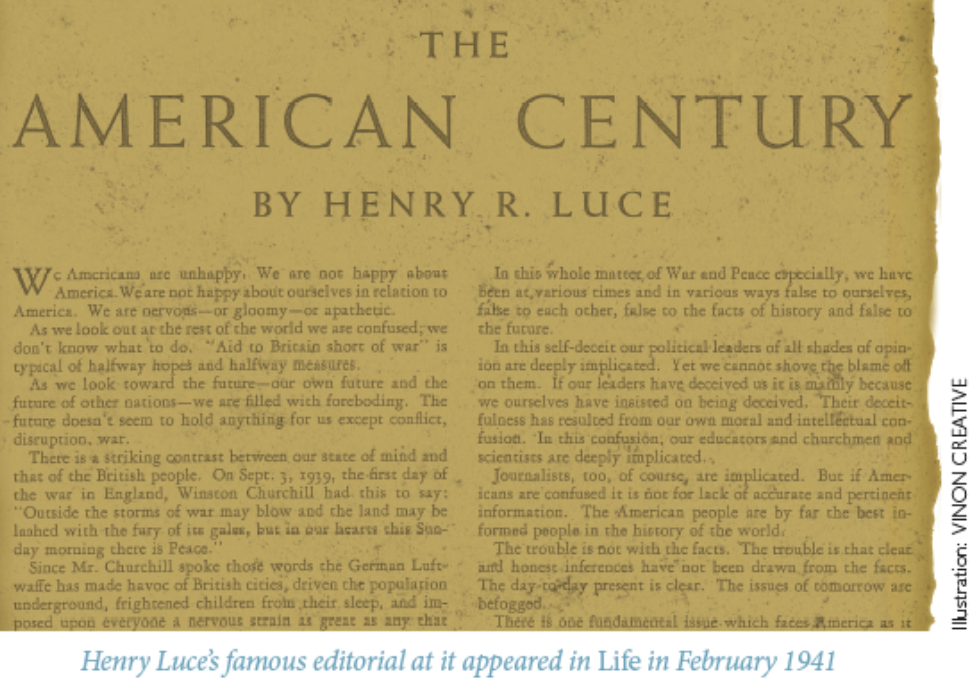

In 1941, Henry Luce—the founder of Time magazine and its sister publications Life and Fortune—famously announced that “the twentieth century is the American Century.” With unparalleled power and unquestioned resolve, the United States would make the world “safe for the freedom, growth, and increasing satisfaction of all.” And it would do so because of a combination of American power and prestige that would engender a near-universal “faith in the good intentions as well as the ultimate intelligence and ultimate strength of the whole American people.”

The remainder of the century saw the United States bestride the world as the dominant power, sometimes for better and sometimes for worse. But Luce was correct that it was the American Century (or at least half-century). As of 2020, though, the twenty-first century has become “the Anti-American Century,” an identity already well-advanced before the pandemic but certainly accelerated and cemented by it.

Necessary Antithesis?

The Anti-American Century may turn out to be aggressively hostile to the United States, but for now it is anti-American mostly in the sense of being antithetical to the American Century. The three pillars of American strength—military, economic, and political—that defined the last century have each been undermined if not obliterated. In this moment, those failures may seem like profound negatives. In his most recent book, the writer Robert Kagan laments that, without American leadership around the world, the jungle will grow back. In America’s absence, Beijing may be able to define a less liberal world order. In terms of domestic politics, the left and the right are oddly united in their despair at the erosion of the American Century, as the left bemoans the failure of the American experiment in an age of

racial divisions and government ineptitude and the right defends to the hilt the “Make America Great Again” redux.

Yet the dawn of the Anti-American Century may be precisely what both the world and the United States need to meet the particular challenges of today. From the end of World War II though the first decades of the twenty-first century, the United States both maintained the global order and destabilized it when that suited its agenda. Whether one saw America as a force for good or a source of ill, it was the reference point as surely as the Roman Empire in its heyday and the British in its. The idea, however, that the world can only stay sane and stable if the United States remains the hegemon is a grim recipe. It assumes that the inevitable fate of nations is a state of nature, a Hobbesian world of power and dominance. That may indeed by inscribed on our collective history, but if there is one lesson of history, it is that things do change, slowly, messily, confusingly, but inevitably. So it ever was is not so it will ever be, and the idea that stability is dependent entirely on a hegemon, benevolent or not, is only one possible pathway.

The other is that a world of nearly 7.8 billion people demands multiple nodes of support, not one hegemon or two jockeying for power. That, after all, was the defining vision when the United Nations was established at the end of World War II. Yes, the structure of the UN also nodded to the fact that powerful nations such as the United States and the Soviet Union would have greater influence than Yugoslavia or Burma, but it also enshrined the idea that only a world defined by a congress of nations rather than hegemons running roughshod would see sustainable peace and prosperity.

Creepingly over the decades, the United States began to see itself as what 1990s Secretary of State Madeleine Albright termed “the indispensable nation,” the sole guarantor of international peace, stability and prosperity. With that came the patois of the United States as “the leader of the free world,” a phrase also liberally applied to the American president. Year by year, that led to a view that a powerful America was synonymous with a stable world, and that a less robust United States therefore spelled global disorder.

Narrative Challenged

The pandemic has deeply challenged that narrative, but move the lens out a bit further, and it’s clear that the pandemic is only the latest, albeit perhaps the most serious, blow to that idea of the United States as the necessary nation keeping the dogs of war at bay and the forces of totalitarianism in check. It may indeed have filled that role in the face of Stalinism in the 1950s, and it may have stood as a counter to the worst deprivations of Soviet Communism and its Eastern European variants. But even if that is largely true, with the end of the Cold War, American power became altogether more ambiguous in its global effects, and since 9/11, even more so. The past two decades culminating in the pandemic have altered the relative position of the United States, especially in diluting its mantle of global leadership even as it retains extraordinary wealth, military power, and a long history of robust—and chaotic—democracy.

If anything good comes out of the present morass, it may be that a United States of great affluence and great deficiencies needs to accept that it is not ordained to lead and that its past results are, as investors like to disclaim, no guarantee of future success. The fact that it was a hegemon is not a reason to continue being one, and behaving as if you are long after the structural realities have changed is the nation-state equivalent of an aged monarch believing that he remains as strong and inviolable as he did as a youth. The analogy is not exact: the United States is not on the verge of expiring, but it is evolving in ways that many Americans have yet to accept. The first step to solving a problem is acknowledging that you have one; failure to do so—to believe that one’s country is uniquely powerful and destined by history and culture for greatness—is a recipe for a fall.

The shift has happened both gradually and rapidly. At the dawn of the new millennium—a scant 20 years ago that feels like an eternity—the United States was able to say to itself and the world that it had found a uniquely potent formula for how to manage democracy. It pointed to its role as a global superpower and its resilient and flourishing economy. It asserted that it had excelled in advanced research, education, and innovation and stood as an example to countries everywhere. All that was never nearly as true as Americans wished it to be, but those strengths were, relative to much of the world, undeniable.

Twenty years into the millennium, the pandemic has exposed structural fissures and weaknesses in the United States. But those fissures were not created by the pandemic. And the power of the U.S. president and executive branch in foreign policy is not matched by commensurate power at home. In normal times, that is a recipe for considerable freedom relative to other countries and a substantial check on would-be infringements of that. But it is also a liability when faced with a threat that demands cohesive national domestic policy. Even had a more competent president been at the helm, these limitations would likely have hobbled an ideal response.

The past months have underscored that a country whose central government is constrained by the three-branch structure of an executive branch distinct from the legislative and in turn checked by the courts is also limited by substantial local and state autonomy is not particularly well-suited to marshaling a forceful national effort that isn’t an actual war. But the tut-tutting and eye-rolling abroad about the anemic American response to the COVID-19 pandemic (“The World is Taking Pity on Us,” went the line in one prominent column and in many other since) is also the next iteration of a process that has been unfolding for two decades. The United States was always likely to fall short in its response to a pandemic given the decentralized nature of its national government, but in the context of the past two decades, those failings have made it impossible to hold the United States as an exceptional nation.

That can seem like a decline; it may actually be a sign of maturity that augurs well for the future of the country and for the globe. If you believe that the world needs hegemons or everything will descend into chaos, then that shift is indeed troubling, If, however, you believe that the twenty-first century will only be stable if multiple nations take responsibility for the world order, then a United States as a normal, albeit immensely powerful, country is to be welcomed.

Three Pillar Knockdown

The first pillar of the American Century to be knocked aside was military. The U.S. invasion of Afghanistan after 9/11 enjoyed considerable support internationally as a justified response to the Taliban’s sheltering of al Qaeda and Osama bin Laden. But the subsequent invasion of Iraq in March 2003 with a paucity of international support followed by a bungled occupation and years of guerrilla war against American troops evoked the Vietnam War.

Initial misgivings were exponentially magnified by revelations of American-sanctioned torture in Iraq, at the Guantánamo Bay detention facility, and at various sites around the world, in clear contravention of the Geneva Conventions that the United States had long defended. Add to that revelations of spying on domestic citizens in the name of national security and the war on terrorism, and many of the pieties of American strength crumbled. By 2008, the United States emerged from its Iraq imbroglio with its military still second-to-none in size and capacity but with its image severely undermined.

The second pillar to crumble was economic. One of the central conceits of Luce’s American Century was that the unique virtues of the American economic system would act as a powerful rebuke of communism. And even after the fall of the Soviet Union, the flourishing American economy was a magnet for talent and innovation, with U.S. technology firms defining the first internet boom of the 1990s and then the next wave in the 2000s.

Meanwhile, the Washington Consensus that coalesced in the 1980s about how to structure free markets was the blueprint for post-1989 reconstruction of Eastern Europe and Russia. It was also used as a loose framework by both the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank in their efforts to push countries around the world to drop trade barriers, end state-run businesses, and open up their capital accounts to global flows. While some countries, especially Russia, suffered mightily from this medicine, the sheer economic power of the United States left little alternative for most nations. China was the notable exception, and its size and the widespread perception that it would eventually move toward the American model after joining the World Trade Organization allowed it to evolve along its own path.

China’s economic success eroded American dominance, but it was the financial crisis of 2008-2009 that truly knocked away the economic pillar. For years, the question in investors’ minds had been: “When would the bad loans on the books of China’s state-owned banks lead to a crash in China?” It turned out that it wasn’t China’s banks that were the problem; it was banks in the United States. And they were a contagion that went global. The U.S.-led financial system survived, but the economic reputation of the United States—the prestige that Luce understood as a key element of its power—was devastated.

The final pillar was democracy. For decades, the United States could boast that it was the oldest and most established democracy in the world, with a singular system for preserving individual freedoms and harnessing collective energies. It routinely nudged and sometimes coerced allies and adversaries to open up and democratize. That in no way precluded dealing with dictators, but the presumption was that democracy was the best bulwark against autocracy and the best path to affluence. The United States, whatever its flaws, got democracy about as right as anyone. It was never quite the “strongest democracy” according to those who measured such things: the Scandinavian countries led there. But America was undoubtedly the strongest of the large and dynamic democracies, which in combination with its other two pillars (military and economic) created the American Century. Then Donald Trump was elected president.

Already by 2016, American democracy was showing signs of strain. Public faith and participation in government had so declined as to put the system on notice. But the election of Trump severely eroded the ability of Americans to say either to themselves or to the world that their process was uniquely able to withstand the pressures of populism and nascent authoritarianism that Americans for decades had preached against. Arguably, Trump has done much less damage than his many critics aver, and that may indeed reflect a domestic system of checks and balances that makes it devilishly difficult for any one president to commit major abuses of power.

But the strength of American democracy in the world was also as a symbol and a beacon, one that drew immigrants and talent because of the opportunities that the United States offered and nurtured. On that score, the Trump Administration dramatically eroded the United States’ global standing. Yes, the image of the United States also suffered mightily in the 1970s, with the humiliation of Vietnam and the revelations of American anti-democratic policies in much of what was then known as the Third World. It is possible that had the economic revival of the 1980s not happened, the American Century would have ended then. It didn’t, but then came the pandemic.

The China Question

Much as Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai once famously said of the legacy of the French Revolution that it was too soon to make final judgments, it is premature to start ranking nations conclusively by how well they met a pandemic that is still raging. It is clear, however, that what may be American strengths in other contexts are in this moment a panoply of weaknesses: decentralized domestic governance, highly contested politics, and immense cultural variations across states and regions. All of those inoculate Americans against autocracy and government overreach but leave the country vulnerable to national crises that require a unified response.

Coming in the midst of the Trump Administration, the American pandemic response has deeply dented if not utterly crushed the image of the United States as an ambassador for good governance and democracy—and with it, the last pillar of the American Century.

Many in both the United States and throughout the world may believe that the end of the American Century is tragic, but the dawn of the Anti-American Century holds the promise of better times for the globe and represents an opportunity for Americans to finally confront their country’s structural problems. After all, unless one believes that the United States has a monopoly on the desire for peace, individual rights, and prosperity, 7.8 billion people and nearly 200 nations large and small are just as capable as Americans of acting in those collective interests. To believe otherwise is to hold that the only formula for international stability and prosperity is an endless continuation of the American Century.

All this inevitably leads to the question of China and its status as an emerging global power, especially as the United States retreats or is forced to retreat. True, China defines rights differently than the United States, and many outside of China may not find that template an appealing one. But the Chinese template remains a Chinese one, propagated by a government that seems quite interested in keeping the global peace even while asserting its power.

One can argue that China is slowly inching its way toward becoming a new global hegemon, but outside its immediate sphere in East and Southeast Asia, it seems uninterested in the internal affairs of other countries and uninterested into extending itself beyond an interest in securing resources through economic policy. That may change as China becomes more powerful, but for now, China is less a threat to most other countries than a threat to the continued American assertion of its status as the most powerful country. In that sense, China is an existential threat to the United States, but in that sense as well, the threat is almost only existential: the rise of China doesn’t much threaten the United States or any other country economically, other than Taiwan and its own embattled internal minorities such as the Uigurs and Tibetans. Those are real issues, but do not in themselves make the case that a rising China proves the need for the United States to remain a hegemon or else the stability of the world is imperiled.

And whatever one thinks of China’s future, it remains true that one would have to think that the United States is somehow a freakish and exceptional nation alone committed to peace and prosperity to believe firmly that the end of the American Century spells a backward step for humanity.

As for the United State domestically, decades of global preeminence have not done Americans well at home in recent years. Standards of living have stagnated and not kept pace with those in numerous other countries. Racism persists. None of the countries that have excelled at education, healthcare, and standards of living are as large or complicated as the United States, but even by its own standards, the country has fallen short of what it once achieved. It spends massively on education, infrastructure, poverty alleviation, healthcare, and defense—but it does not manage to spend smartly. Yes, material life is better now for almost everyone than it was 50 years ago: people live longer, have more healthcare, eat better, are more educated, live in safer cities and towns; but that is true everywhere in the world. The United States cannot toot its own horn here.

The simple fact is that success and strength—military, political, economic, and to that add cultural—are not birthrights. The United States doesn’t get to be great or powerful just because it used to be, although it certainly can help to have a head start. If the country was ever truly exceptional, it was exceptional because successive generations worked and fought and struggled to make it so, not because those generations patted themselves on the back. There have been acute moments of hubris and overreach during the decades of the American Century, but never has the disconnect between what the United States is and what Americans say it is been so profound.

Out of this moment, therefore, should arise the promise not of American exceptionalism but American humility, a moment of recognition that, to move forward, the United States has to let go of the American Century, say goodbye to exceptionalism, and accept that it is a normal country like any other, just richer and with a massive military arsenal and multiple wells of strength and multiple areas of self-delusion. The end of the American Century offers the opportunity to look at where the country falls short and start fixing what is broken. Who knows whether Americans will seize that opportunity. But this end is not a tragedy; it is the beginning of something new.