Atman Trivedi is Managing Director of Hills & Company, having previously served as the Bureau of International Security and Nonproliferation Chief of Staff at the U.S. State Department. You may follow him on Twitter @AtmanMTrivedi.

Atman Trivedi is Managing Director of Hills & Company, having previously served as the Bureau of International Security and Nonproliferation Chief of Staff at the U.S. State Department. You may follow him on Twitter @AtmanMTrivedi.

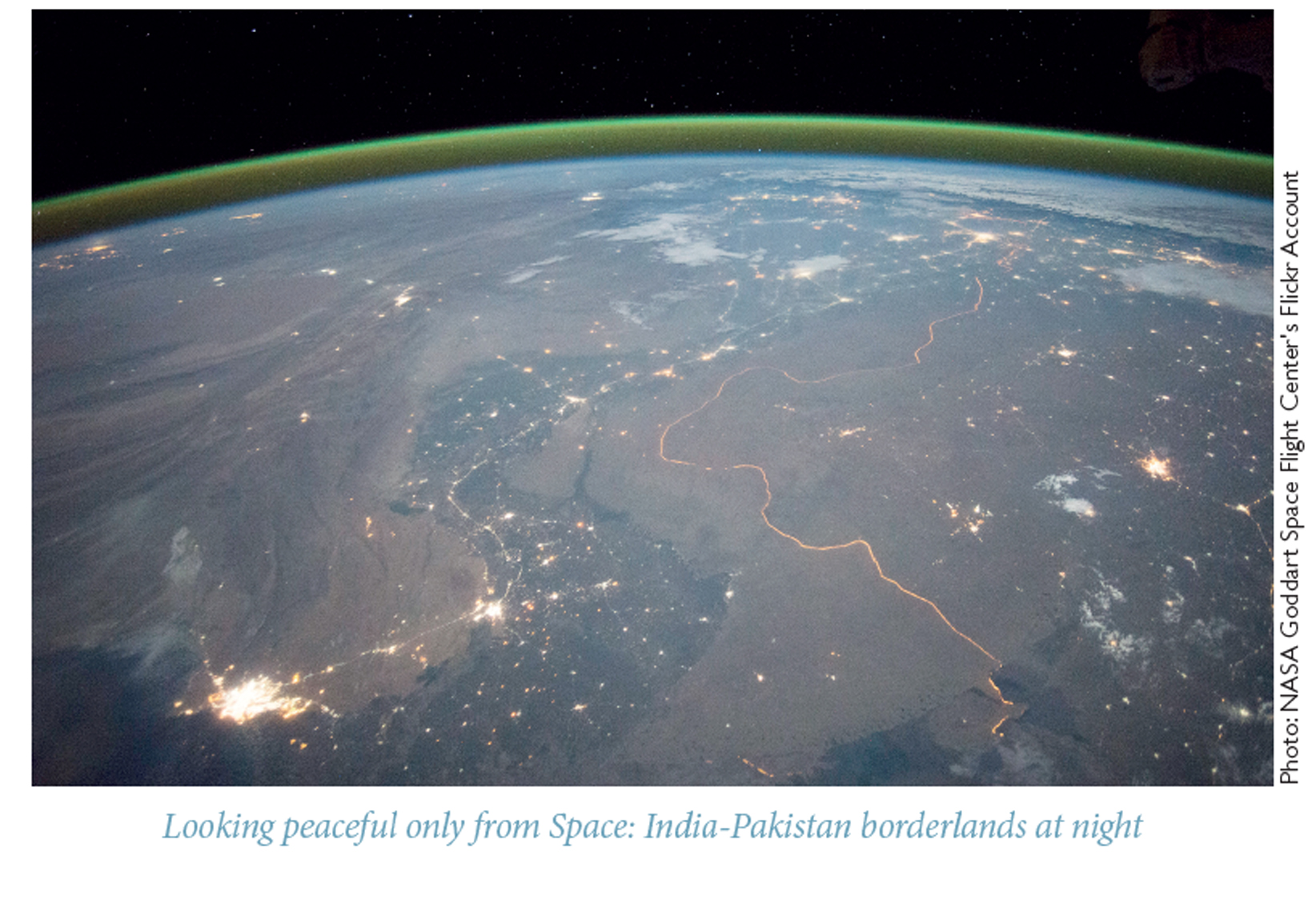

February 2019 witnessed a direct military confrontation between two nuclear-armed states. Fighter jets raced across enemy lines and engaged each other in aerial combat, as the world watched and waited. The moment of maximum danger between India and Pakistan has thankfully receded—for the time being. The concern now is that South Asia returns to business as usual, while the international community moves on to other pressing challenges.

A Pakistan-based terrorist attack set in motion a significant escalation of force by both capitals—one that could have resulted in disaster. That it was averted adds to the overconfidence in both countries regarding their governments’ respective abilities to manage conflict in the shadow of nuclear weapons. Divergent, nationalist narratives about what happened and why have become entrenched; to this toxic brew must be added the growing salience of nuclear weapons in military planning in Pakistan and, now, possibly in India, as well as a gradual regional arms race.

With both countries seemingly determined to draw the wrong lessons from this confrontation, the risk of nuclear war in South Asia is growing. Without steps being taken within the region to address its causes—starting with Pakistan’s tendency to light the fuse, supplemented by effective U.S. diplomacy, the next crisis in South Asia is more likely to involve the first use of nuclear weapons since 1945.

Setting the Scene

On February 14th, 2019, a young Kashmiri detonated suicide bombs in Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir (J&K). The attack killed about 40 Indian paramilitary soldiers in Pulwama. The young man was a local recruit of Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM), a Pakistan-based terrorist group designated as such by both the United Nations and the United States.

JeM immediately claimed responsibility. On February 26th, the Indian Air Force launched strikes inside recognized Pakistan territory (as opposed to disputed J&K, where much of the past fighting has occurred) to raze a suspected JeM training camp. The next day, Pakistan also conducted strikes on non-military targets in Indian-administered J&K. Pakistan downed an Indian jet that entered its airspace in hot pursuit, and captured the pilot.

The crisis was finally defused when, reportedly under pressure from the United States and others, Pakistan safely returned the pilot. Almost everything else about these events is shrouded in mystery.

Pakistan-based Terrorism

What is not obscured by the fog of contradictory facts and dueling national narratives is that JeM and other well-known terrorist outfits operate openly in Pakistan. In the recent past, they have served as useful instruments for the state’s military-intelligence complex to wage a proxy war against neighboring Afghanistan and India.

After Pulwama, Prime Minister Imran Khan repeatedly sought to convince the international community that Pakistan has turned the page on terrorism, telling foreign journalists in April that the country had “no use” for “armed militias” anymore. To match his words with action, Khan will need to convince the powerful Pakistan Army and the country’s premier intelligence service, the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), that jettisoning extremists is in their interest.

The PA and ISI have historically regarded militant groups as useful asymmetric tools. They can compensate for the relative weakness of Pakistan’s conventional military forces and the country’s lack of strategic depth. Terrorist operations planned by Pakistan-based organizations have spawned India-Pakistan crises in 2001-2002, 2008, 2016, and 2019. These attacks were orchestrated either by JeM or Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), another Pakistan-based terrorist group under UN and U.S. terrorism sanctions. Even as JeM claimed responsibility for the latest carnage, ISI’s public diplomacy arm suggested the assault was “some sort of [a] staged incident.”

Pakistan’s inveterate grievances against India over Kashmir and also other topics, the roughly one quarter of the state budget that the military commands to deal with the perceived threat, and the lack of civilian authority over the military combine to make a clean break between the military and terrorist groups unlikely.

The country’s deployment of nuclear weapons and, in particular, low-yield tactical bombs have allowed Islamabad to operate largely with impunity—that is, until India’s airstrike on Balakot. New Delhi found that, in responding to Pakistan-based terrorism, its hands felt unduly constrained, if not tied, by Pakistan’s possession of nuclear weapons and apparent willingness to use them. As described by long-time South Asia expert Ashley Tellis, New Delhi felt restricted over the years in at least two ways: Initially, it instinctively would exercise caution and practice “self-deterrence” to steer clear of a larger crisis. Subsequently, following the initial bout of terrorism, calls for restraint would inevitably cascade from a concerned international community.

Indian Retaliation

In 2008, heavily-armed LeT extremists laid siege to Mumbai over a four-day period, attacking a handful of landmarks and well-known sites. Yet, the specter of all-out war between the nuclear-armed combatants prompted then-Prime Minister Manmohan Singh to avoid firing a single shot. Singh’s Indian National Congress Party-led governing coalition was replaced in 2014 with a more nationalist and assertive government led by the Bharatiya Janata Party’s Narendra Modi. The new prime minister touted a more muscular approach to national security. (On occasion, literally: He has boasted of having a 56-inch chest.)

In 2016, in response to a JeM-planned attack in Indian-administered J&K that killed 19 soldiers, India retaliated with what it called “surgical strikes” by the army against militant launch pads across the de facto border dividing Kashmir (known as the Line of Control). In February 2019, India upped the ante further, scrambling fighter jets to hit targets inside undisputed Pakistani territory—the first such occurrence in about 50 years. The air raid also marked another “first”: a nuclear-armed country using air-power against another. Until then, both sides observed an important confidence-building measure that restricted planes and helicopters from flying within certain distances of the Line of Control.

Each prior crisis does not necessarily set the bar for the next. The leaders’ personalities, the nature of the provocation, the prevailing national mood, and other factors influence crisis decisionmaking. But the decisions made in the latest conflict serve as relevant benchmarks for political leaders, the security establishments, and citizens in both countries to consider if and when tensions next come to a boil.

The trend in India is moving towards progressively tougher responses. The ruling government cleared an important psychological and normative hurdle in escalating retaliatory action. And in the wake of Modi having won reelection decisively this spring, the jingoistic fervor consuming social media and rabid evening news programs have put India in a less patient and tolerant head-space after Uri and Balakot. The BJP government actively stoked Hindu nationalism by playing up its resolute response after Pulwama (and Uri) to the hilt, while doing or saying virtually nothing that would draw salutary scrutiny to the Indian military’s actual performance in the crisis. Playing to the crowd at a late April election rally in Rajasthan, Modi noted how security experts warned of Pakistan’s nuclear button, and asked his partisans: “Have we kept our nuclear bomb for Diwali?”

From Muslim-majority Pakistan’s perspective, the uncertainty surrounding the tactical effectiveness of India’s airstrikes will likely detract from their deterrent effect. Pakistani politicians, diplomats, and citizens may be in the dark about what happened at Balakot, but the military can assess what was accomplished. Thus far, no evidence has been presented to show any damage occurred to a terrorist training camp or that there were casualties, as asserted by the Indian government.

Competing Nationalisms

In Islamabad, many Pakistani elites regard the military exchange as “the country’s finest hour.” The view from the capital and surrounding parts is of a scrappy underdog more than holding its own on the battlefield, while appearing steady and even statesmanlike in de-escalating confrontation. Never mind that the security establishment’s ties to terrorists helped trigger the crisis, or have led to the international community’s growing weariness with Pakistan’s taste in friends.

Across the border in New Delhi, there is jubilation that a more powerful, rising India is finding its voice and finally acting decisively, rather than wallowing in victimhood. Understandably eager to point the finger of blame at Pakistan-based terrorism, the Indian public appears in no mood to consider the growing disaffection of majority Muslim, Indian-administered J&K, where the excesses of Indian security forces and lack of economic opportunity present an inviting environment for religious extremists.

Stoked by the martial tone and content of their press, the two countries’ triumphalism raises serious questions about whether current and future governments will underestimate the risks inherent in future clashes and grow overconfident about the careful, calibrated way in which each is said to have used military force.

Escalation in Crisis

For some knowledgeable observers, the limited Indian airstrike on targets in Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, just across the border from disputed Pakistan-administered J&K, did not constitute a severe reprisal. Similarly, the Khan government is also said to have launched a measured air response confined to disputed Indian-held J&K, declining to attack recognized Indian territory. Both sides’ public statements were cloaked in legalese, while emphasizing efforts to minimize casualties and collateral damage.

Yet, when cast in a broader light, despite the evident care shown in resorting to the diplomacy of violence, India and Pakistan displayed a virtually unprecedented degree of risk acceptance among nuclear-armed antagonists. India’s airstrike marked the first attack across the international border since the 1971 war that turned East Pakistan into Bangladesh (and which also predated India’s “peaceful nuclear explosion” in 1974, the first nuclear test in South Asia). The only other instance when nuclear-armed states have clashed occurred back in 1969, when China (an incipient nuclear power) and the Soviet Union skirmished along the Ussuri River. During those tensions, Moscow made discrete inquiries through Soviet diplomats to see how Washington would register a preemptive nuclear strike on China.

It is not hard to envision the recent tit-for-tat escalation leading to alternate endings. For instance, what would have happened if the Indian pilot, Abhinandan Varthaman, whose MiG-21 was shot down, had not survived that encounter, or had died while in Pakistani custody? Or what if Khan had opted against the timely return of the pilot as a gesture of good faith, or had not issued such a stark and sincere-sounding call for peace following

Pakistan’s airstrikes?

National Security Adviser Ajit Doval told his American counterpart, John Bolton, as well as U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, that India was prepared for the worst should Varthaman be harmed, according to the Hindustan Times.

Meanwhile, on the evening of February 27th, the heads of India and Pakistan’s preeminent intelligence agencies were allegedly also in communication about a potential escalation.

The two spymasters reportedly discussed the Indian army’s deployment of twelve short-range, surface-to-surface missile batteries in Rajasthan. Reuters reported that India threatened to fire half a dozen missiles at Pakistan, and Islamabad warned it would escalate with a larger conventional strike of its own. Khan himself stated on February 28th, “I know last night there was a threat [that] there could be a missile attack on Pakistan, which got defused.” He added, “I know [that] our army stood prepared for retaliation to that attack.”

Had the countries climbed these additional rungs up the escalation ladder, how close were they to a decision that might trigger the use of nuclear weapons (such as an Indian ground campaign into Pakistan proper)?

As things stand, Pakistan trumpeted a meeting of its principal decisionmaking body related to nuclear weapons, the National Command Authority, for the day after the Indian sortie, which was a move likely intended to intimidate Indian policymakers and force international diplomats to call for restraint. Both sides wanted to steer far clear of the nuclear brink, and tried to leave themselves off-ramps. The countries also apparently had key lines of communication open, yet neither could be sure that their shot was the last.

Neither army mobilized for combat during the crisis. But as tensions escalated, the Indian Navy operationally deployed its combat units, including its carrier battle group, nuclear submarines, and scores of other ships, submarines, and aircraft. Pakistan similarly increased the alert levels of its own naval and naval air capabilities.

Nuclear experts have documented how mobilizing forces in this manner can result in inadvertent escalation. As South Asia scholar Christopher Clary has noted, in August 1999, about a month after the Kargil conflict (so named for a district in J&K), an Indian MiG-21 shot down a Pakistan Navy plane near the international border. That event spawned accusations and counter-accusations about what happened, where, and who was to blame; it serves as a reminder that unplanned confrontations sometimes can and do happen in South Asia.

Learning to Love the Bomb?

India and Pakistan are walking the escalation tightrope in crises against the backdrop of a gradual nuclear arms race and potential changes in doctrine that lower the threshold for the bomb’s use in conflict. The antagonists are investing heavily in nuclear weapons and their delivery. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, Pakistan has roughly 140-150 nuclear warheads compared to India’s 130-140 warheads. Asia is the only continent where atomic arsenals are growing; although, to be fair, this still only accounts for 3 percent of the global total.

India’s nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine INS Arihant became operational in 2016, with several more to follow. Its induction gave the country a “nuclear triad,” namely the ability to launch nuclear strikes by land, air, and sea. India is developing long-range ballistic missiles capable of hitting targets throughout China.

Meanwhile, Pakistan is working on submarine-launched cruise missiles to secure its own triad, and it already possesses low-yield, nuclear warheads to target Indian troops and armored vehicles. Pakistan regards its nuclear capabilities as a “full spectrum” deterrent against any type of military attack by India, including in retaliation to Pakistan-based terrorism. The country’s nuclear umbrella provided a sense of invulnerability that was punctured by its archenemy at Balakot. If nuclear weapons were to be used in South Asia, the odds are that Pakistan would strike first.

During the height of the recent confrontation, Lieutenant General Tariq Khan, a former commander of Pakistan’s key land-based strike formation, the I Corps (located in J&K), advocated for an aggressive posture in comments posted on Facebook and reported on by Firstpost. In response to an Indian cross-border strike, Khan declared “[o]ur response should be to escalate and push the envelope of hostilities so that nuclear war is a likely outcome.”

To be clear, the retired general was not spoiling for nuclear war, but he was willing to wager his country’s survival on the view that “the rungs in the escalation ladder are so many” and that India—as the larger, wealthier state—would decide it had more to lose in an all-out war.

Historically, India has had a “no first use” policy not to strike first with nuclear weapons. The country’s pledge is consistent with its longstanding posture of maintaining a minimum, credible deterrent. However, Clary and scholar Vipin Narang argue in a recent piece for International Security that India may be developing nuclear forces that can attack Pakistan’s own preemptively. The pair raise sobering questions about whether India’s development of diverse and growing nuclear capabilities, alongside various public statements about the benefits of preemptive options against Pakistan, signal a new openness to targeting its neighbor’s longer-range nuclear systems in a conflict.

India’s March 27th, 2019 anti-satellite test shows it can place China’s space assets at risk if its own are threatened, but New Delhi can also leverage that technology as part of basic missile defense against Pakistan to hit incoming nuclear warheads in space. Antimissile systems would offer India cold comfort against a nuclear first strike by Pakistan, but New Delhi may think it can mop-up residual nuclear forces left behind after an initial, disarming Indian attack.

In short, the test could put Pakistan on edge about its second-strike capability, cause the country to accelerate its bomb-making activities, and make it think harder about going nuclear first in a conflict.

Interestingly, neither the Congress Party nor BJP national election manifestos made any reference to nuclear weapons. In its 2014 platform, BJP devoted an entire section to promising to “revise and update [India’s nuclear doctrine and] to make it relevant to [the] challenges of current times;” at the same time, the platform stated that India under a BJP government would “[m]aintain a credible minimum deterrent.” Does today’s silence speak volumes about a desire to expand the size and roles of its stockpile to maximize flexibility?

The overall trajectory in South Asia points to Pakistan, and now perhaps India, seeking greater room to maneuver around the logic of Mutual-Assured Destruction, just as the United States and Soviet Union did, at times, during the Cold War. In those days, there were near-misses, such as crises in Berlin in 1958-1961 and Cuba in 1962. Long-term scholar Scott Sagan and others have shown over the years how the two countries were fortunate to avoid nuclear catastrophe resulting from breakdowns of command and control and accidents. Each superpower sought the capability to target the other’s bombs, while protecting their own. In the 1970s and ‘80s, both sides eventually gave up on diversifying their battlefield nuclear weapons, rejected “nuclear warfighting” doctrines, and accepted the inescapability of mutual vulnerability. Neither ever felt confident enough to directly attack the other with even conventional forces, because of the lingering fear of massive retaliation.

In South Asia, India and Pakistan crossed this threshold in 1999, 2016, and 2019.

Pakistan has already shown a willingness to ratchet up tensions through the use of terrorist proxies. Will both now seek the upper hand through the further escalation of future crises? With Pakistan pushing to the brink and India entertaining forward-leaning doctrines, the countries’ increasing confidence in exploring the limits of deterrence through finely-calibrated violence represents a concerning new phase in South Asia’s nuclear evolution.

Getting Ready for the Next Crisis

The path to reducing nuclear threats in the region runs through Rawalpindi, the general headquarters of the Pakistan Army. Prime Minister Khan has issued several positive and clear denunciations of extremism and taken some initial steps to reign-in terrorists based in Pakistan.

But any serious policy shift will require the unequivocal support of the Chief of Army Staff and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee, as observed recently by South Asia expert Peter Lavoy. Khan needs to find out how much his good relationship with the military is worth. Pakistan’s refusal to blacklist JeM’s founder and leader Masood Azhar (who operates freely in the country), backed until recently by its “iron brother” China, should temper anyone’s expectations regarding a reduction in tolerance of terrorist groups.

India’s policy options are limited, but it can ill-afford to opt out of diplomacy. The country is successfully gathering international support for isolating Pakistan in response to its ties to terrorists. New Delhi and its democratic allies in the Americas, Europe, and Asia are, alone, unlikely to produce a change in the Pakistan military’s short-term behavior, as long as countries like China, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE invest heavily in the nation. As Tellis has argued, India must therefore focus in large part on what it can control: investments in counter-terrorism, preparedness for the next attack, and national resilience.

Contrary to Islamabad’s claims, the root causes of the fraught India-Pakistan relationship extend beyond the deteriorating J&K situation. Their calamitous history, growing power asymmetries, virulent nationalism, and the powerful bureaucratic imperative for the Pakistan military to justify its centrality to the state all present daunting obstacles to peace.

Nevertheless, India should expect Pakistan to continue pointing to the steadily intensifying alienation and resentment in the Kashmir Valley as the main source of their interstate rivalry. Freedom House has actually found that political rights and civil liberties in Pakistan-administered J&K are more restricted than in its Indian counterpart. The fact remains, however, that an overly-militarized Indian policy has enabled the conditions for extremist groups like JeM to maneuver in J&K, and has facilitated opportunities for Rawalpindi to pick at a festering wound through proxies.

After Pulwama, India

faces two kinds of temptations to preserve the upper hand in the next potential crisis. It can call its neighbor’s nuclear bluff again, but this time seek to deter Pakistan-based terrorism through an even more robust conventional response. At the same time, India can intentionally introduce greater ambiguity over its nuclear weapons policies moving forward. Both steps present nuclear risks. The former increases the threat of conflict spiraling out-of-control towards the unthinkable; the latter creates incentives for Pakistan to lower the threshold for using the bomb or entertain a disarming nuclear first strike in response to the added uncertainty.

External Actors

In today’s environment, the United States remains the only global power that can play a significant role in avoiding a nuclear catastrophe. China is too pro-Pakistan while Russia has, at least historically, been too pro-India (and is most comfortable playing the spoiler); Europe, of course, is too divided and distracted. Even America’s scope in facilitating prudent decision-making may be shrinking.

As the recent confrontation wore on, and in its immediate aftermath, Washington faced criticism for being too passive as the missiles started to fly. Early in the crisis, the Trump Administration asserted India’s “right to self-defense” (as Bolton put it). As the conflict unfolded, its circumspection in public pronouncements contrasted with concerted, behind-the-scenes pressure on Pakistan (allowing Islamabad to sue for peace without a humiliating climbdown). In a mid-March piece in Reuters, senior American officials sought to convey a well-coordinated effort at the highest levels of government to get Pakistan to exercise restraint. India, on the other hand, was afforded latitude in conducting what was generally regarded by the administration as a counter-terrorism operation in Balakot.

The American response in the days after Pulwama represents the next step in an ongoing shift from being an “honest broker” in India-Pakistan conflicts to one that stands decisively with the world’s largest democracy and against violent extremism. That evolution started in Kargil back in 1999, and accelerated after the horrific 2008 Mumbai siege. Following India’s “surgical strikes” after the attack at Uri, a senior White House official (for the Obama Administration) said “we do empathize with the Indians’ perception that they need to respond militarily.”

The bipartisan shift constitutes sound policy. Hope springs eternal that it will help force Pakistan to reassess the costs of allowing terrorists to operate in plain sight. But this clarity does not come without a price, as former White House official Joshua White has pointed out. The willingness of the United States to back Indian retaliation in a time of crisis might embolden New Delhi to raise the stakes, while simultaneously imposing new limitations on Washington’s ability to get Islamabad to stand down. Having observed or participated in over a dozen war games simulating India-Pakistan conflicts, White noted the difficulties in assessing whether and how each step draws the countries closer to the nuclear threshold.

Questions over the future role of the United States in a crisis—at a time when India’s impatience with Pakistan may be seeping into its nuclear policies—underscore the urgency and immediacy with which America and its allies should pressure Pakistan anew to crackdown on terrorism.

In some respects, the Trump Administration is well-positioned to do this. Long before the latest confrontation, it decided to get tough on Pakistan. If the Pakistan Army and ISI are unwilling to change, the United States should press for the Financial Action Task Force to blacklist heavily-indebted Pakistan—a step that may lead to a downgrade with global lenders and ratings agencies. The country should be investing in its people, not violent groups like JeM. Over time, the costs associated with the country’s isolation may produce a reassessment in Rawalpindi.

Pakistan’s security establishment is seen by American negotiators as central to a peaceful settlement with the Taliban that would end the Afghan war. Recently, the military has been playing a constructive role in helping move the Afghan Taliban; the international community must insist it do the same with militants eyeing its eastern border with India. Only demonstrable signs of progress in fighting terrorism will

produce conditions under which a resumption of a broader India-Pakistan dialogue can, in turn, lead to lasting peace.

Finally, the greater risks associated with a future conflict underscore the importance of careful, discrete U.S. nuclear diplomacy with India—and, to the extent it is possible, separately, with Pakistan. Experienced, high-level security professionals should regularly exchange views on crisis decision-making, escalation dynamics, and the role of nuclear weapons. These sensitive, small group discussions should be insulated from swings in bilateral relations, and must be kept quiet.

Without serious efforts by policymakers and a thoughtful public debate in South Asia on the recent conflict’s lessons, existing trends and tendencies will be reinforced. A return to normalcy makes the next crisis only a matter of time—and likely more dangerous. The United States needs to do what it can to help push off that confrontation and assist now in managing its attendant risks.