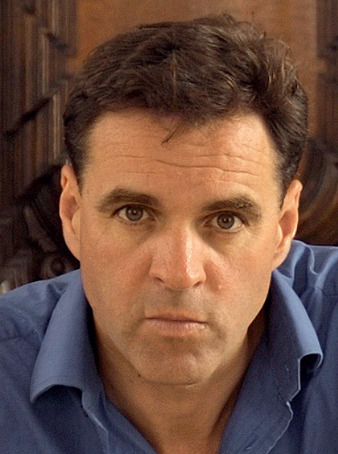

Niall Ferguson is the Milbank Family Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University, and a Senior Faculty Fellow of the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard University. He is also Founder and Managing Director of Greenmantle LLC, an advisory firm. He is the author of 16 books, including his most recent, Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe (2021). An earlier version of this essay appeared as a chapter in Hal Brands and Francis J. Gavin (eds.), COVID-19 and World Order: The Future of Conflict, Competition, and Cooperation. (2020).You may follow him on Twitter @nfergus.

Niall Ferguson is the Milbank Family Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University, and a Senior Faculty Fellow of the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard University. He is also Founder and Managing Director of Greenmantle LLC, an advisory firm. He is the author of 16 books, including his most recent, Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe (2021). An earlier version of this essay appeared as a chapter in Hal Brands and Francis J. Gavin (eds.), COVID-19 and World Order: The Future of Conflict, Competition, and Cooperation. (2020).You may follow him on Twitter @nfergus.

In Liu Cixin’s extraordinary science fiction novel The Three-Body Problem (2006), China recklessly creates, then ingeniously solves, an existential threat to humanity. During the chaos of Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution, Ye Wenjie, an astrophysicist, discovers the possibility of amplifying radio waves by bouncing them off the sun and in this way beams a message to the universe. When, years later, she receives a response from the highly unstable and authoritarian planet Trisolaris, it takes the form of a stark warning not to send further messages. Deeply disillusioned with humanity, she does so anyway, betraying the location of Earth to the Trisolarans, who are seeking a new planet because their own is subject to the chaotic gravitational forces exerted by three suns (hence the book’s title). So misanthropic that she welcomes an alien invasion, Ye co-founds the Earth-Trisolaris Organization as a kind of fifth column, in partnership with a radical American environmentalist. Yet their conspiracy to help the Trisolarans conquer Earth and eradicate humankind is ingeniously foiled by the dynamic duo of Wang Miao, a nanotechnology professor, and Shi Qiang, a coarse but canny Beijing cop.

The nonfictional threat to humanity we confront today is not, of course, an alien invasion. The coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 does not come from outer space, though it shares with the Trisolarans an impulse to colonize us. The fact, however, is that the first case of COVID-19—the disease the virus causes—was in China, just as the first messages to Trisolaris were sent from China. Similar to The Three-Body Problem, the Communist Party of China (CPC) caused this disaster—first by covering up how dangerous SARS-CoV-2 was, then by delaying measures that might have prevented its worldwide spread. Yet within a few months—again, as in Liu Cixin’s novel—China sought to claim credit for saving the world from it. Liberally exporting testing kits, face masks, and ventilators, the Chinese government sought to snatch victory from the jaws of a defeat it inflicted. Not only that, but the deputy director of the Chinese Foreign Ministry’s Information Department went so far as to endorse a conspiracy theory that the coronavirus originated in the United States. In mid-March 2020, Zhao Lijian tweeted: “It might be [the] U.S. army who brought the epidemic to Wuhan.” Zhao also retweeted an article claiming that an American team had brought the virus with them when they participated in the World Military Games in Wuhan in October 2019. And Beijing went on to export more than 200 million doses of its four homegrown vaccines to 90 countries—a bold attempt to engage in what used to be a mainly Western game of vaccine diplomacy.

It was already obvious early in 2019 that a new cold war—Cold War II, between the United States and China—had begun. What started out in early 2018 as a trade war—a tit for tat over tariffs while the two sides argued about the American trade deficit and Chinese intellectual property theft—had by the end of that year metamorphosed into a technology war over the global dominance of the Chinese company Huawei in 5G (fifth generation) network telecommunications; an ideological confrontation, in response to Beijing’s treatment of the Uyghur minority in China’s Xinjiang region and the pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong; and an escalation of old frictions over Taiwan and the South China Sea. Henry Kissinger himself acknowledged in November 2019 that we are “in the foothills of a Cold War.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has merely intensified Cold War II, at the same time revealing its existence to those who less than just two years ago doubted it was happening. Chinese scholars such as Yao Yang, a professor at the China Center for Economic Research and Dean of the National School of Development at Peking University, now openly discuss it. Proponents of the era of U.S.-China “engagement” since 1972 are now writing engagement’s obituary, ruefully conceding (in Orville Schell’s words) that it foundered “because of the CPC’s deep ambivalence about the way engaging in a truly meaningful way might lead to demands for more reform and change and its ultimate demise.” Critics of engagement are eager to dance on its grave, urging instead that the People’s Republic be economically “quarantined,” with its role in global supply chains drastically reduced. To quote Daniel Blumenthal and Nicholas Eberstadt, “The maglev from ‘Cultural Revolution’ to ‘Chinese Dream’ does not make stops at Locke Junction or Tocqueville Town, and it has no connections to Planet Davos.”

Moves in the direction of economic quarantine are already happening. The European Chamber of Commerce in China said last year that more than half its member companies were considering moving supply chains out of China. Japan has earmarked 240 billion yen ($2.2 billion) to help manufacturers leave China. “People are worried about our supply chains,” Prime Minister Shinzo Abe said in April 2020. “We should try to relocate high added value items to Japan. And for everything else, we should diversify to countries like those in ASEAN.” In the words of Senator Josh Hawley of Missouri, a Republican: “The international order as we have known it for thirty years is breaking. Now imperialist China seeks to remake the world in its own image, and to bend the global economy to its own will. [...] [W]e must recognize that the economic system designed by Western policymakers at the end of the Cold War does not serve our purposes in this new era.” In early May 2020, Missouri’s attorney general, Eric Schmitt, filed a lawsuit in federal court seeking to hold Beijing responsible for the outbreak. The election of a new president has not significantly changed the trajectory of the superpower relationship. At his meeting with China’s Yang Jiechi in Alaska in March 2020, Secretary of State Antony Blinken stated: “The United States’ relationship with China will be competitive where it should be, collaborative where it can be, adversarial where it must be.”

To be sure, many voices have been raised to argue against Cold War II. Yao Yang has urged China to take a more conciliatory line toward Washington, by acknowledging what went wrong in Wuhan in December 2019 and January 2020 and eschewing nationalistic “wolf warrior” diplomacy. A similar argument for reconciliation to avoid the “Thucydides Trap” has been made by Yu Yongding and Kevin Gallagher. Eminent architects of the strategy of engagement, notably Hank Paulson and Robert Zoellick, have argued for its resurrection. Wall Street remains as addicted as ever to the financial symbiosis that Moritz Schularick and I christened “Chimerica” in 2007, and Beijing’s efforts to attract big U.S. financial firms such as American Express, Mastercard, J. P. Morgan, Goldman Sachs, and BlackRock into the Chinese market are proving successful.

Nevertheless, the political trend is quite clearly in the other direction. In the United States, public sentiment toward China has become markedly more hawkish since 2017, especially among older voters. There are few subjects these days about which there is a genuine bipartisan consensus in the United States. China is one of them.

It is therefore stating the obvious to say that Cold War II will be the biggest challenge to world order for most of President Joe Biden’s term in office. Thanks to revelations contained in John Bolton’s memoir, The Room Where It Happened—which revealed President Donald J. Trump to have been privately a good deal more conciliatory toward his Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinping, than he was in public—the Biden campaign was able to claim that their man would be tougher on China than Trump. Indeed, statements made during the race by people who were in the running for cabinet-level appointees in a Biden Administration (Michèle Flournoy’s June 2020 Foreign Affairs article, for instance) were so tough in places as to be indistinguishable from those of Trump’s Secretary of State Mike Pompeo. Biden’s key foreign policy appointments—Secretary of State Antony Blinken and National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan—have also been notable for the combative nature of their statements about China. In his April 2021 address to a Joint Session of Congress, Biden himself said that Xi Jinping was “deadly earnest about becoming the most significant, consequential nation in the world” and that America and China were in “competition” to “win the twenty-first century.”

Big Player Weaknesses

Commentators (and there are many) who doubt the capacity of the United States to reinvigorate and reassert itself imply, or state explicitly, that this is a cold war the Communist power can win. “Superpowers expect others to follow them,” Kishore Mahbubani told Der Spiegel in August 2020. “The United States has that expectation, and China will too, as it continues to get stronger.” In a April 2020 interview with the Economist, he went further: “History has turned a corner. The era of Western domination is ending.” This view has long had its supporters among left-leaning or sinophile Western intellectuals, such as Martin Jacques and Daniel Bell.

The COVID-19 crisis made it more mainstream. Yes, the argument runs, the fatal virus may have originated in Wuhan, whether in one of the local “wet markets” where live wild animals are sold for their meat or (as seems increasingly plausible) in one of two biological research laboratories located in the city. Nevertheless, after an initially disastrous sequence of events, the Chinese government was able to get the contagion under control with remarkable speed, illustrating the strengths of the “China model,” and then to bend the global narrative in its favor, recasting itself as the savior rather than scourge of humankind.

By contrast, the United States under Trump badly bungled its pandemic response. “America is first in the world in deaths, first in the world in infections and we stand out as an emblem of global incompetence,” then retired U.S. diplomat and now CIA Director William Burns told the Financial Times in May 2020. “The damage to America’s influence and reputation will be very hard to undo.” The editor-in-chief at Bloomberg, John Micklethwait, and his co-author Adrian Wooldridge wrote in a similar vein in April 2020. “If the twenty-first century turns out to be an Asian century as the twentieth was an American one,” wrote Lawrence Summers in May 2020, “the pandemic may well be remembered as the turning point.” Nathalie Tocci, who advises the EU’s High Representative, Josep Borrell, has likened this moment to the 1956 Suez Crisis. The American journalist and historian Anne Applebaum has written: “there is no American leadership in the world. [...] [T]he outline of a very different, post-American, post-coronavirus world is already taking shape. [...] A vacuum has opened up, and the Chinese regime is leading the race to fill it.” Those who take the other side of this argument—notably Gideon Rachman and Joseph Nye—are in a distinct minority. Even Richard Haass, who argues that “the world following the pandemic is unlikely to be radically different from the one that preceded it,” sees a dispiriting future of “waning American leadership, faltering global cooperation, great-power discord.”

Meanwhile, those who believe in historical cycles, such as hedge-fund-manager-turned-financial-historian Ray Dalio, are already writing the obituary for a dollar-dominated world economy. The historian Peter Turchin has made a similar argument on the basis of “structural demographic theory,” predicting in 2012 in a Journal of Peace Research article that the year 2020 would be “the next instability peak [of violence] in the United States.”

As Henry Kissinger argued in an April 2020 Wall Street Journal essay, the pandemic “will forever alter the world order. [...] The world will never be the same after the coronavirus.” But how exactly will the international system change? One possible answer is that COVID-19 has reminded many countries of the benefits of self-reliance. In Kissinger’s words: “Nations cohere and flourish on the belief that their institutions can foresee calamity, arrest its impact and restore stability. When the COVID-19 pandemic is over, many countries’ institutions will be perceived as having failed. Whether this judgment is objectively fair is irrelevant.”

Not everyone shares Daniel Bell’s ecstatic assessment of the performance of the Chinese Communist Party. True, the Chinese response to the pandemic is not going to be remembered as Xi Jinping’s Chernobyl. Unlike its Soviet counterpart in 1986, the Communist Party of China had the ability to weather the storm of a disaster and to restart the industrial core of its economy. True, Xi did not meet his goal of having China’s 2020 gross domestic product be double that of 2010: COVID-19 necessitated the abandonment of the growth target that was necessary to achieve that, although China was still the only major economy to post gains last year. But Premier Li Keqiang was able to announce in March 2021 a “target over 6 percent” growth for this year.

Nevertheless, Xi should not be regarded as unassailable, notwithstanding ceremonial events such as the centenary of the Communist Party of China celebrated in Tiananmen Square in early July 2021. Sentiment towards China generally, and Xi in particular, has become markedly more negative because of the pandemic, as international survey data published by the Pew Group has shown. All told, it was always a little naïve to have assumed that China was likely to be the net beneficiary of the pandemic.

However, that is not to say that the United States is somehow emerging from the pandemic panic with its global primacy intact—even with a new president who likes to say that “America is back.” The ineffective U.S. response to the pandemic was not simply a product of Trump’s bungling—and bungle he did, with tragically avoidable consequences. Much more troubling was the realization that the parts of the U.S. federal government that are responsible for handling a crisis such as this also bungled it. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services is a mansion with many houses, but the ones that were charged with pandemic preparedness appear to have failed abjectly: not only the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention but also the Food and Drug Administration, the Public Health Service, as well as the National Disaster Medical System. This was not for want of legislation. In 2006, the U.S. Congress passed a Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act, in 2013 a reauthorization act of the same name, and in June 2019 a Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness and Advanced Innovations Act. In October 2015, the bipartisan Blue Ribbon Study Panel on Biodefense, cochaired by Joe Lieberman and Tom Ridge, published its first report, calling for better integration of the agencies responsible for biodefense. In 2019 it was renamed the Bipartisan Commission on Biodefense “to more accurately reflect its work and the urgency of its mission.”

During the Trump Administration, Robert Kadlec, a career U.S. Air Force doctor, was Assistant Secretary of Health and Human Services for preparedness and response. In October 2018, Kadlec gave a lecture at the University of Texas’s Strauss Center on the evolution of biodefense policy in which he quoted from Nassim Taleb’s Black Swan (2010) as part of his argument for an insurance policy against a pandemic. “If we don’t build this,” concluded Kadlec, “we’re gonna be ‘SOL’ [shit out of luck] should we ever be confronted with it. [...] We’re whistling in the dark, a little bit.” The previous month, the Trump Administration had published a thirty-six-page report, National Biodefense Strategy (2018). Its implementation plan included as one of its five goals: “Assess the risks posed by research, such as with potential pandemic pathogens, where biosafety lapses could have very high consequences.”

As a consequence of the failure of the public health bureaucracy during the pandemic, the United States fell back on the 1918-1919 playbook of pandemic pluralism (states do their own thing; in some states a lot of people die) but combined it with the 2009-2010 playbook of financial crisis management. A significant part of the national economy was shut down by state governors in March and April 2020; meanwhile the national debt exploded, along with the Federal Reserve system’s balance sheet. By May 2020, lockdowns had become intolerable for most Republicans, but state governments were nowhere near having the integrated systems of testing and contact tracing necessary for economic reopening to be anything other than “dumb,” in the formulation of “grumpy economist” John Cochrane. As this debacle played out, it was like watching all my earlier visions of the endgame of American empire—in the trilogy Colossus (2004), Civilization (2011), and The Great Degeneration (2012)—but speeded up.

Admittedly, things have improved since the inauguration of Biden. For example, the country easily met the goal of achieving 100 million vaccinations in the first 100 days of the new administration. This was, in fact, a success partly inherited from the Trump Administration, which had done a surprisingly good job of supporting and expediting the development of vaccines (Operation Warp Speed). Yet only a few months later, the White House had to admit it would not meet its ambitious COVID-19 vaccination goal of administering at least one jab to 70 percent of adults by its July 4th Independence Day holiday.

The truth is that this crisis has exposed the weaknesses of all the big players on the world stage: not only the United States but also China and, for that matter, the European Union. This should not surprise us. History shows that plagues are generally bad for big empires, especially those with porous frontiers (witness the reigns of the Roman emperors Marcus Aurelius and Justinian); city-states have tended to be better at limiting the spread of pathogens. In 2019 the new Global Health Security Index ranked the United States first and the United Kingdom second in the world in terms of their “global health security capabilities.” It proved otherwise.

A league table of coronavirus health safety published in early April 2020 by the Deep Knowledge Group put Israel, Singapore, New Zealand, Hong Kong, and Taiwan at the top. (Iceland deserved an honorable mention, too. And some second-tier great powers—notably Germany and Japan—also did relatively well, minimizing infections and deaths without inflicting severe damage on their economies.) Taiwan belatedly had a COVID-19 outbreak in May-June 2021 but swiftly brought it under control. The key point is that there are diseconomies of scale when a new pathogen is on the loose. Four of those countries, in their different ways, had reasons to be paranoid in general as well as focused on the specific danger of a new coronavirus. Israel, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Taiwan had learned the lessons of SARS and MERS. By contrast, the big global players—China, the United States, and the EU—all did quite badly in 2020, each in its own distinctive way. The winners in the short run were none of the above empires. The winners were today’s equivalents of city-states.

The question is: Who gains from this demonstration in Israel, Singapore, and Taiwan that, in a public health crisis, small can be beautiful? On balance, I would say that the centrifugal forces unleashed by the pandemic are a much bigger threat to a monolithic one-party state than to a federal system that was already in need of some decentralization. And to which of the three empires do the successful city-states feel most loyalty? That is the real question.

Trump’s Actions & Objectives

As Kissinger observed last year, “No country [...] can in a purely national effort overcome the virus. [...] The pandemic has prompted an anachronism, a revival of the walled city in an age when prosperity depends on global trade and movement of people.” Ultimately, Taiwan cannot prosper in isolation; no more can South Korea. “Addressing the necessities of the moment,” Kissinger writes, “must ultimately be coupled with a global collaborative vision and program. Drawing lessons from the development of the Marshall Plan and the Manhattan Project, the U.S. is obliged to undertake a major effort [...] [to] safeguard the principles of the liberal world order.”

After the Trump Administration’s ignominious political end—capped by a second impeachment for inciting a domestic insurrection on January 6th, 2021—its reputation unsurprisingly remains at rock bottom in the eyes of most scholars of international relations. Trump continues to be seen as a wrecking ball who took wild swings at the very institutions on which the liberal world order supposedly depends, notably the World Trade Organization and the World Health Organization, to say nothing of the Joint Plan of Action on Iran’s nuclear program and the Paris Agreement on the climate. Yet reasonable questions may be asked about the efficacy of all of these institutions and agreements with respect to the Trump Administration’s core strategy of engaging in “strategic competition” with China, as defined by the 2017 National Security Strategy of the United States. If an administration is judged by its actions in relation to its objectives, rather than by presidential tweets in relation to some largely mythical liberal international order, a rather different picture emerges. In four distinct areas, the Trump Administration achieved, or stood within striking distance of achieving, meaningful success in its competition with China. The fact that the Biden Administration largely continued Trump’s China strategy was the ultimate testament to this success.

The first was financial. For many years, China toyed with the idea of making its currency convertible. This proved to be impossible because of the pent-up demand of China’s wealth owners for assets outside China. More recently, Beijing sought to increase its financial influence through large-scale lending to developing countries, some of it (not all) through its Belt and Road Initiative.

The crisis unleashed by the COVID-19 pandemic presented the United States with an opportunity to reassert its financial leadership in the world. In response to the severe global liquidity crisis unleashed in March 2020, the Federal Reserve created two new channels—swap lines and a repo facility for foreign international monetary authorities—by which other central banks could access dollars. The first already applied to Europe, the United Kingdom, Canada, Japan, and Switzerland and was extended to nine more countries, including Brazil, Mexico, and South Korea. At its peak, the amount of swaps outstanding was $449 billion. In addition, the new repo facility made dollars available on a short-term basis to 170 foreign central banks. At the same time, the International Monetary Fund—an institution the Trump Administration showed little inclination to undermine—stepped in to manage a spate of requests for assistance from around 100 countries, canceling six months of debt payments due from twenty-five low-income countries such as Afghanistan, Haiti, Rwanda, and Yemen, while the G20 countries had agreed to freeze the bilateral debts of 76 poorer developing countries. As international creditors braced themselves for a succession of defaults by countries such as Argentina, Ecuador, Lebanon, Rwanda, and Zambia, the United States found itself in a much stronger position than China. Since 2013, total announced lending by Chinese financial institutions to Belt and Road Initiative projects amounted to $461 billion, making China the single biggest creditor to emerging markets. The lack of transparency that characterized these loans long ago aroused the suspicions of Western scholars, notably Carmen Reinhart, now chief economist at the World Bank.

It is one thing to lament the dominance of the dollar in the international payments system; it is another to devise a way to reduce it. Unlike in the 1940s, when the U.S. dollar stood ready to supplant the British pound as the international reserve currency, the Chinese renminbi still remains far from being a convertible currency, as Hank Paulson and others have pointed out. Chinese and European experiments with central bank digital currencies pose no greater threat to dollar dominance. As for Facebook’s grand design for a digital currency, Libra, it “has about as much chance of displacing the dollar,” one wit observed, “as Esperanto has of replacing English.”

The most that could be said is that the United States lags worryingly behind Asia, Europe, and even Latin America when it comes to innovations in financial technology. But it is hard to see how even the most ambitious scheme—the projected East Asian digital currency consisting of the Chinese yuan, Japanese yen, South Korean won, and Hong Kong dollar—will come to fruition, in view of the profound suspicions many in Tokyo feel toward the financial ambitions of Beijing. The most plausible threat to the dominance of the dollar would be if China’s new central bank digital currency (e-CNY or e-yuan) begins to be used for significant cross-border transactions, but that still seems a distant prospect.

The second area where U.S. dominance was reasserted in 2020 was in the race to find a vaccine against SARS-CoV-2. Starting in May 2020, leading private vaccine research projects received U.S. government funding as part of the Trump Administration’s Operation Warp Speed, the White House program for accelerating vaccine development. These included AZD1222, first developed by researchers at Oxford and Vaccitech, and six others. True, at the time there were also five vaccines in clinical trials in China, but four of them are inactivated whole-virus vaccines—an earlier generation of medical science than Moderna’s mRNA-1273 or BioNTech’s mRNA vaccine, developed in partnership with Pfizer. An early April 2020 survey in Nature noted that “most COVID-19 vaccine development activity is in North America, with 36 (46 percent) developers of the confirmed active vaccine candidates compared with 14 (18 percent) in China, 14 (18 percent) in Asia (excluding China) and Australia, and 14 (18 percent) in Europe.”

It was also worth remembering the recurrent problems the People’s Republic has had in recent years with vaccine safety and regulation, most recently in January 2019, when children in the province of Jiangsu received out-of-date polio shots, and before that in July 2018, when 250,000 doses of vaccine for diphtheria, tetanus, and whooping cough were found to be defective. It was only less than 15 years ago that Zheng Xiaoyu, the former head of the Chinese State Food and Drug Administration, was sentenced to death for taking bribes from eight domestic drug companies.

True, at least two of the Chinese contenders beat the odds and produced COVID-19 vaccines: Sinovac Biotech brought CoronaVac to market and Sinopharm’s Beijing Institute of Biological Products produced two other vaccines. But even China’s most successful vaccines have underperformed the leading Western ones. Recent outbreaks in Mongolia, Bahrain, Chile, and the Seychelles—even after majorities of their populations have been vaccinated—have raised hard questions about how well the Chinese vaccines work.

Third, in important ways the United States pulled ahead of China in the “tech war.” The Trump Administration’s pressure on allied countries not to use 5G hardware produced by Huawei yielded rather impressive results. In Germany, Norbert Röttgen, a prominent member of Chancellor Angela Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union, helped draft a bill that would bar any “untrustworthy” company from “both the core and peripheral networks.” In Britain, Neil O’Brien, Conservative member of Parliament and founder of the China Research Group, and a group of thirty-eight rebel Tory backbenchers succeeded in changing Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s mind about Huawei, much to the fury of the editors of China Daily. Perhaps more significant were the U.S. Commerce Department rules announced in May 2020 that cut Huawei off from using advanced semiconductors produced anywhere in the world using U.S. technology or intellectual property. This includes the chips produced in Taiwan by the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, or TSMC, the world’s most advanced manufacturer. These restrictions posed a potentially mortal threat to Huawei’s semiconductor affiliate HiSilicon.

Finally, the United States’ lead in artificial intelligence research, as well as in quantum computing, would appear still to be commanding. One recent study showed that, while “China is the largest source of top-tier AI researchers, [...] a majority of these Chinese researchers leave China to study, work, and live in the United States.” Writing in Foreign Affairs, Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne concluded their June 2020 survey of the tech war as follows: “If we look at the 100 most cited patents since 2003, not a single one comes from China. [...] A surveillance state with a censored Internet, together with a social credit system that promotes conformity and obedience, seems unlikely to foster creativity.” If Yan Xuetong, Dean of the Institute of International Relations at Tsinghua University, is correct in contending that Cold War II will be a purely technological competition—without the nuclear brinkmanship and proxy wars that made the first one so risky and so costly—then the United States is the favorite to win it.

At the end of the day, no one in the Trump Administration wanted to claim that it was, in Kissinger’s words, “safeguard[ing] the principles of the liberal world order.” It would nevertheless be fair to say that, in practice, that the Trump Administration was quite effective in at least some of the steps it took to execute its stated goal of competing strategically with China. This policy and its achievements have been inherited by the Biden Administration, which appears in important respects to wish to continue to implement it.

Less Success Ahead?

The great achievement of the various strategies of containment pursued by the United States during the Cold War was to limit and ultimately reverse the expansion of Soviet power without precipitating a World War III.

Might strategic competition with China prove less successful in that regard? It is possible. First, there is a clear and present danger that information warfare and cyberwarfare operations, honed by the Russian government and now being adopted and enacted by China, could cause severe disruption to the U.S. political and economic system.

Second, as Christian Brose has argued, the United States could find itself at a disadvantage in the event of a conventional war in the South China Sea or the Taiwan Strait, because U.S. aircraft carrier groups, with their F-35 fighters, are now highly vulnerable to new Chinese weapons such as the DF-21D, the world’s first operational anti-ship ballistic missile (“the carrier killer”).

Third, the United States already finds it difficult to back up words with actions. China imposed new national-security laws on Hong Kong, dealing a blow to the territory’s autonomy and surely violating the terms of the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration, which guarantees a “one country, two systems” model until 2047. Adding various Chinese agencies and institutions to the U.S. Commerce Department’s entity list did not deter Beijing from going ahead. Nor have similar economic sanctions threatened by indignant U.S. senators.

The case of Taiwan is different, because the island is de facto an autonomous democratic polity, even if Beijing insists that it is a province of the People’s Republic. U.S. Secretary of State Pompeo went out of his way to show friendliness toward the Taiwanese government in 2020, publicly congratulating President Tsai Ing-Wen on her reelection in January 2020. The April 2021 visit to Taipei by former U.S. Senator Chris Dodd and two former Deputy Secretaries of State, James Steinberg and Richard Armitage, was a further sign of continuity with the Trump era. Indeed, in some ways, Biden has gone farther than Trump. For instance, for the first time in four decades, a serving U.S. ambassador has visited Taiwan. Right after the inauguration, Blinken’s State Department issued a clear statement of support for Taiwan in response to a large incursion by Chinese military aircraft. Subsequently, the U.S. Navy conducted several rounds of patrols in the Taiwan Strait and even signed a coastguard agreement with Taipei. Moreover, U.S. arms sales to Taiwan are on track to increase in 2021.

Yet how effectively could the United States react if Beijing decided to launch a surprise amphibious invasion of the island? Such a step is openly proposed by nationalist writers on Chinese social media as a solution to the threat that Huawei will be cut off from TSMC. One lengthy post on this subject, published in 2020, was headlined “Reunification of the two sides, take TSMC!”

The reunification of Taiwan and the mainland is Xi Jinping’s most cherished ambition and is one of the justifications for his removal of term limits. During his early July 2020 Tiananmen Square address, Xi Jinping was unambiguous. China, he said, maintained an ”unshakable commitment” to reunification with Taiwan. In what appeared to be a clear signal to the United States, he added that “no one should underestimate the resolve, the will, and the ability of the Chinese people to defend their national sovereignty and territorial integrity.” While the Pentagon remains skeptical of China’s ability to execute a successful invasion, the People’s Liberation Army is rapidly increasing its amphibious capabilities. With good reason, Graham Allison warned in a 2020 essay in The National Interest that America’s ambition to “kill Huawei” could end up playing a role similar to the sanctions imposed on Japan between 1939 and 1941, culminating in the August 1941 oil embargo. It was economic pressure that ultimately drove the imperial government to gamble on a war that began with a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor.

Cold wars can deescalate in a process we remember as détente. But they can also escalate: a recurrent feature of the period from the late 1950s until the early 1980s was fear that brinkmanship might lead to Armageddon. At times, as John Bolton has shown in his aforementioned memoir, Trump inclined to a very crude form of détente, and important members of his administration leaned in that direction, too. We even heard occasional melodious mood music about the phase one trade deal announced in late 2019, despite abundant evidence that it was being honored by Beijing mainly in the breach.

Yet the language of Trump’s Secretary of State remained consistently combative. For instance, his meeting with Yang Jiechi, China’s most senior foreign policy official, in Hawaii in June 2020 was notable for the uncompromising harshness of the language used in the official Chinese communiqué released afterward. So far, as we have seen, the Biden Administration has continued this approach. If anything, the tone was even worse in March during the meetings in Anchorage, Alaska, between Yang Jiechi and Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi, on the one hand, and Blinken and Sullivan, on the other.

Persuading Allies

It is generally agreed by scholars that in Cold War I allies played a crucial role in ensuring that the United States prevailed over the Soviet Union. It mattered a great deal that the North Atlantic Treaty Organization was formed and endured as a deterrent against Soviet aggression in western Europe. How likely is the same thing to be achieved if this is indeed Cold War II? Can Americans appeal to Europeans as they did in the 1950s and 1960s?

In some quarters, the answer is clearly no. The Italian foreign minister, Luigi Di Maio, was one of a number of Italian politicians all too ready to swallow Beijing’s aid and propaganda back in March 2020, when the COVID-19 crisis in northern Italy was especially bad. “Those who scoffed at our participation in the Belt and Road Initiative now have to admit that investing in that friendship allowed us to save lives in Italy,” Di Maio declared in an interview. The Hungarian prime minister, Viktor Orbán, was equally enthusiastic. “In the West, there is a shortage of basically everything,” he said in an interview with Chinese state television. “The help we are able to get is from the East,” he continued. “China is the only friend who can help us,” gushed the Serbian president, Aleksandar Vučić, who actually kissed a Chinese flag when a team of doctors flew from Beijing to Belgrade.

However, other European attitudes, especially in Germany and France, have been very different. “Over these months China has lost Europe,” Reinhard Bütikofer, a German Green Party member of the Bundestag, declared in an interview in April 2020. “The atmosphere in Europe is rather toxic when it comes to China,” said Jörg Wuttke, president of the EU Chamber of Commerce in China. In April 2020, the Editor-in-chief of Germany’s biggest tabloid, Bild, published an open letter to Xi Jinping titled “You are endangering the world.” In France, too, Chinese “wolf warrior diplomacy” was a failure.

One reason for this failure is that, after an initial breakdown in early March 2021, when sauve qui peut was the order of the day, EU institutions rose to the challenge posed by COVID-19. In a remarkable interview published in April 2020, the French president declared that the EU faced a “moment of truth” in deciding whether it was more than just a single economic market. “You cannot have a single market where some are sacrificed,” he told the Financial Times. “It is no longer possible [...] to have financing that is not mutualized for the spending we are undertaking in the battle against COVID-19 and that we will have for the economic recovery.” He continued: “If we can’t do this today, I tell you the populists will win—today, tomorrow, the day after, in Italy, in Spain, perhaps in France and elsewhere.” His German counterpart agreed. Europe, declared Angela Merkel, was a “community of fate” (Schicksalsgemeinschaft).

To the surprise of skeptical commentators, the result was very different from the cheese-paring that characterized the German response to the global financial crisis. The NextGenerationEU plan, presented by the European Commission on May 27, proposed 750 billion euros of additional EU spending, to be financed through bonds issued by the EU and to be allocated to the regions hardest hit by the pandemic. Perhaps even more significantly, the German federal government adopted a supplementary budget of 156 billion euros (4.9 percent of gross domestic product) followed by a second fiscal stimulus package worth 130 billion euros (or 3.8 percent of gross domestic product), which—along with large-scale guarantees from a new economic stabilization fund—was intended to ignite recovery with a “ka-boom,” in the words of Finance Minister Olaf Scholz. Such fiscal measures, combined with large-scale asset purchases by the European Central Bank, did much to dampen support for the populist right in most EU member states. European politics shifted back towards the middle ground—a change personified by former ECB president Mario Draghi’s appointment as prime minister of Italy.

Yet this successful step down the federalist road within the EU—made easier by the departure of the United Kingdom from the intra-EU negotiating table—has had an unexpected consequence from the vantage point of Washington. Europeans, especially young Europeans and especially Germans, have never since 1945 been more disenchanted with the transatlantic relationship. In one pan-European survey conducted in mid-March 2020, 53 percent of young men and women from EU countries said they had more confidence in authoritarian states than democracies when it came to addressing the climate crisis. In a German poll published by the Körber Foundation in May 2020, 73 percent of Germans said that their opinion of the United States had deteriorated—more than double the number of respondents who felt that way toward China. Just 10 percent of Germans considered the United States to be their country’s closest partner in foreign policy. And the proportion of Germans who prioritized close relations with Washington over close relations with Beijing went down to 37 percent—roughly the same share as those who preferred China to the United States (36 percent). These numbers have improved slightly better since Joe Biden took office, but they remain worse than they were before the Trump presidency.

In the Cold War with the Soviets, it is sometimes forgotten that there was a Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), which had its origins in the 1955 Bandung Conference hosted by Indonesian president Sukarno and attended by the Indian prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, the Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser, his Yugoslav counterpart Josip Broz Tito, and the Ghanaian president Kwame Nkrumah, as well as the North Vietnamese president Ho Chi Minh, the Chinese premier Zhou Enlai, and the Cambodian prime minister Norodom Sihanouk. Formally constituted in 1956 by Tito, Nehru, and Nasser, NAM’s goal was (in the words of one of Nehru’s advisers) to enable the newly independent countries of the Third World to preserve their independence in the “face of [a] complex international situation demanding allegiance to either of the two warring superpowers.” For most Western Europeans and many East and Southeast Asians, however, nonalignment was not an attractive option. That was partly because the choice between Washington and Moscow was a fairly easy one—unless the Red Army’s tanks were rolling into a country’s capital city. It was also because NAM’s geopolitical nonalignment was not matched by a comparable ideological nonalignment, a feature that became more prominent with the ascendancy of the Cuban dictator Fidel Castro in the 1970s, finally leading to a near breakup of the movement over the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

Today, by contrast, the choice between Washington and Beijing looks to many Europeans like a choice between the frying pan and the fire or, at best, the kettle and the pot. As the Körber poll mentioned above strongly suggests, “the [German] public is leaning toward a position of equidistance between Washington and Beijing.” Even the government of Singapore has made it clear that it “fervently hope[s] not to be forced to choose between the United States and China.” Moreover, “Asian countries see the United States as a resident power that has vital interests in the region,” the prime minister of Singapore, Lee Hsien Loong, wrote in the July/August 2020 issue of Foreign Affairs. “At the same time, China is a reality on the doorstep. Asian countries do not want to be forced to choose between the two. And if either attempts to force such a choice—if Washington tries to contain China’s rise or Beijing seeks to build an exclusive sphere of influence in Asia—they will begin a course of confrontation that will last decades and put the long-heralded Asian century in jeopardy. [...] Any confrontation between these two great powers is unlikely to end as the Cold War did, in one country’s peaceful collapse.”

Lee Hsien Loong is right in one respect at least. The fact that both world wars of the twentieth century had the same outcome—the defeat of Germany and its allies by Britain and its allies—does not mean that Cold War II will have the same outcome as it predecessor: the victory of the United States and its allies. Cold wars are usually regarded as bipolar; in truth, though, they are always three-body problems, with two superpower alliances and a third nonaligned network in between. This may indeed be a general truth about war itself: that it is seldom simply a Clausewitzian contest between two opposing forces, each bent on the other’s subjugation, but more often a three-body problem—reminiscent of Liu Cixin’s book—in which two large bodies with strong gravitational pulls complete to attract potentially neutral third parties.

The biggest geopolitical problem facing the President of the United States of America today—and for years to come—is that many erstwhile American allies are seriously contemplating nonalignment in Cold War II. And without a sufficiency of allies, to say nothing of sympathetic neutrals, Washington may well find Cold War II to be unwinnable.