Milo Lompar is a Professor in the Department of Serbian Literature at the Faculty of Philology of the University of Belgrade. This essay is based on a lecture delivered in November 2019 at Israel’s Ono Academic College on the occasion of the launch of its Studies of Serbian Language, Culture, and History of Serbian Jewry program.

Milo Lompar is a Professor in the Department of Serbian Literature at the Faculty of Philology of the University of Belgrade. This essay is based on a lecture delivered in November 2019 at Israel’s Ono Academic College on the occasion of the launch of its Studies of Serbian Language, Culture, and History of Serbian Jewry program.

As the world recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic, questions concerning the future of national cultural identities risk being subsumed by what is understood in some circles to be more pressing matters. Without getting into the thorny issue of rank-ordering, as Nietzsche would put it, relegating such questions to the margins of contemporary public discourse not only does a great disservice to the future of all nations but in fact may also pose a grave danger to those that, for one reason or another, are not fully masters of their own destiny. And such nations are in the majority: throughout history, the great powers have been few in number. This essay is intended to help us come to grips with such questions through the prism of a particular example—that of the cultural identity of the Serbian nation—at what may very well turn out to be an inflection point in more ways than one.

As in the history of any other nation, for the Serbs there are a certain number of nodal points in the past that have shaped its national identity under different influences and circumstances. In his book Topographie des Fremden (1997), German phenomenologist Bernhard Waldenfels explains why: “in the lives of individuals, as in the lives of entire nations and cultures, there are certain events ‘that are not forgotten’ because they establish a symbolic order, imprint meaning, revive history, demand answers, generate obligations.” When we compare how German newspapers wrote about the Serbs in 1914-1918 and how they did in 1990-1995, we can observe a striking similarity in terms of both typology and content. The characteristics of Serbian culture, of the Serbian nation, and of Serbian behavior were presented in virtually the same way, whether in caricatures or satirical and analytical texts. The airplane has changed greatly from 1918 to 2000; so has the automobile. But symbolic and cultural conceptions in people’s minds last much longer.

Unlike technological changes, symbolic and cultural conceptions do not undergo rapid change. Even the uncontrolled circulation of information in the virtual world—or even technological and cybernetic changes that have marginalized artistic and spiritual life—cannot rapidly or easily change the invisible action of cultural factors. For it was such changes that created today’s world in which—to quote the Norwegian historian of ideas Trond Berg Eriksen—“symbolic transactions form an important part of social, political and cultural life.” For these same symbolic transactions belong to inherited or altered cultural contents. Culture is not only the fruit of an individual’s spiritual experience—great spiritual achievements in poetry, art, and architecture. In these fields Serbian culture has achieved significant results, some of which are in fact global results. However, there is also something called “cultural policy” and something called the “cultural contribution to collective self-understanding.”

It is all this that creates the world of culture in the broadest sense, because it provides a roadmap for interpersonal communication and the basis for understanding the widest possible variety of things. It is a decisive factor in shaping both national identity in particular and human identity in general—obviously, national identity does not represent human identity as a whole. The human personality is much broader than any identification—national or religious. However—also obviously—national identity is a component of the totality of human identity. To truncate one’s nationality means to truncate something from one’s personality.

This refers to coercive acts. However, if an individual acting alone chooses his pattern of existence—including choosing his national identity—such a choice is associated with individual freedom, and not with the nation. But we often find ourselves amidst collective movements on which social and cultural engineering has a decisive impact. Thus, we face a question that concerns itself with understanding Serbia’s cultural and national existence as two wholes—as categories of their own. This question is older than the question of a legal or state framework (or other frameworks of existence, for that matter); yet at the same time it is not separate from that question. However, the cultural existence of the Serbian nation, at this moment, is a decisive factor in thinking about and determining our overall national survival, understood as constituting our collective survival.

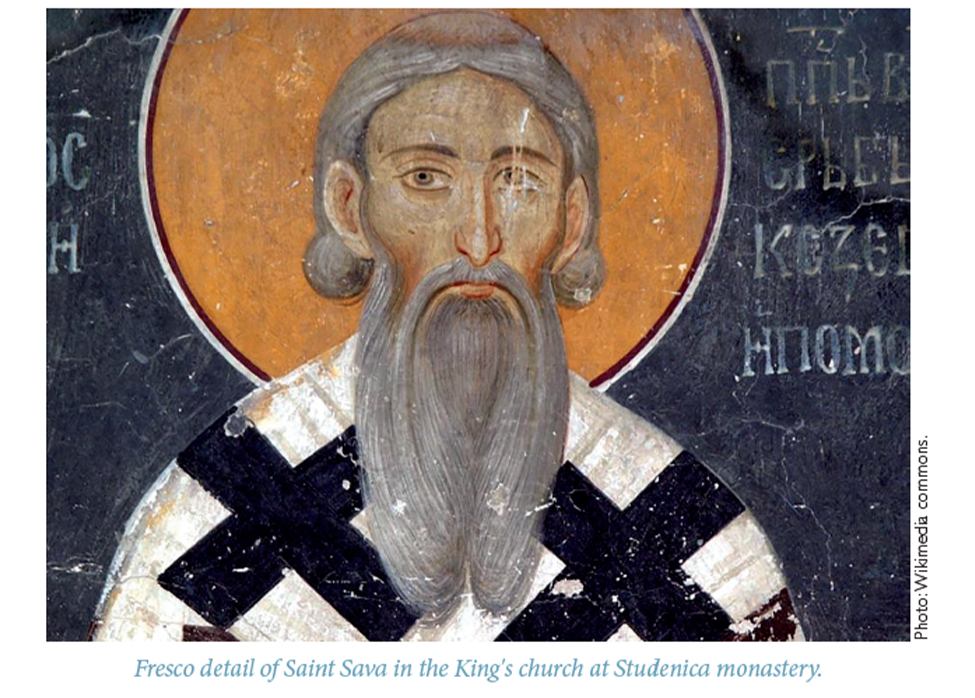

Saint Sava

If we were to list the dominant moments of Serbian cultural existence, then we would have to start from what constitutes its founding moment: the enlightening, educating tradition founded by Saint Sava. The distinctive mark left by Saint Sava’s personality on the historical existence of the Serbian nation undoubtedly represents the starting point in the education and shaping of our nation’s collective self-understanding. The youngest son of Grand Župan Stefan Nemanja—the founder of the Nemanjić dynasty that ruled the medieval Serbian state for over two centuries—Sava became a monk on Mount Athos at a young age. Later, he went on to found and organize the autocephalous Serbian Archbishopric (1219), make a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, and shape the decisive currents in art, language, and literature of the Serbian nation that lasted for centuries thereafter.

We can also see that his personality achieved a status of great predominance in our medieval historical existence by the fact that it embodied two foundational traditions: the sacral and the secular. The medieval tradition of sacral expression made Saint Sava into a representative of the Serbian nation’s high art and culture. It is also important to note that he was the founder of the monastic and ascetic tradition of our nation’s spiritual expression, which left a clear mark on Serbian frescoes and monasteries. This spiritualism can be found in what has been called the “biblical historicism” of later thinkers. They fulfilled the historical existence of the nation with Christian (Old Testament) pathos and eschatological perspective.

Even during his lifetime, popular or folkloric tradition took over important elements of the description of Saint Sava’s character, which produced a rather unique amalgamation. Thus, in the legendary account of the relationship between Saint Sava and the wolf—as historian Vladimir Ćorović has written—we see a merger between the paradigmatic figure of the wolf, which represents pre-Christian antiquity, and the paradigmatic figure of the saint, which represents the Christian tradition. This means that in the Serbian collective self-understanding, the personality of Saint Sava was chosen as the integrative personality of Serbian culture, as it enabled the merger of different cultural traditions.

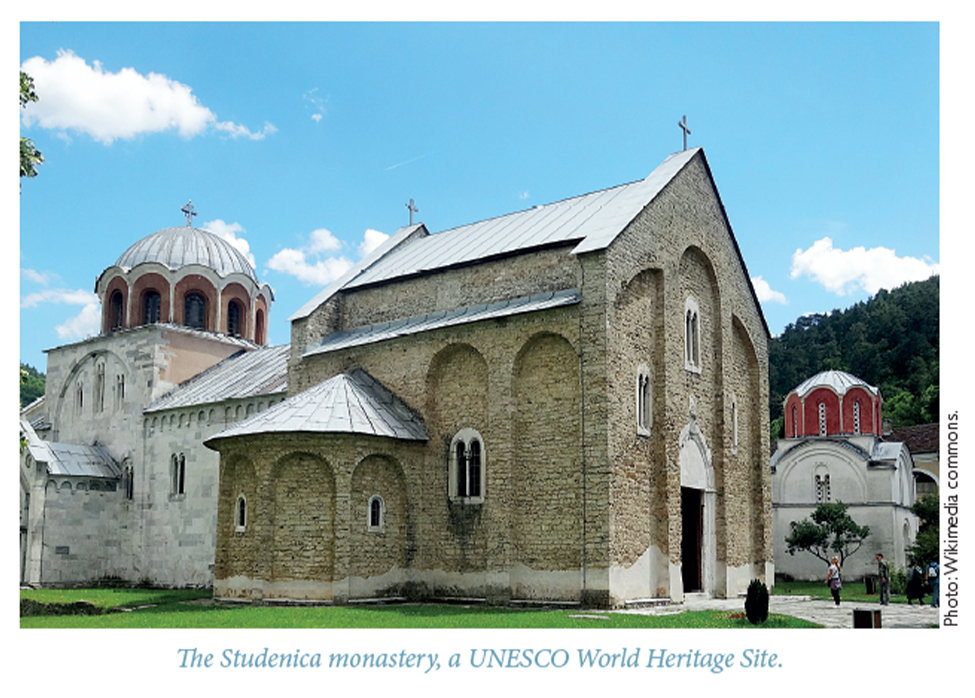

But Serbian culture at its onset emerged as a culture of contact—if one can put it this way—because the Nemanjić state included both Orthodox and Catholic regions. When we examine the decorative façades and architecture of the Studenica and Dečani monasteries, for example, we find many traces of the artistry of master craftsmen from Kotor and southern Apulia. There is, therefore, evidence of Latinity in our medieval artistic tradition. To this, however, one must add that fresco painting was always a Byzantine tradition and that it was, and remains, the popular bearer of the Orthodox message.

Kosovo

The second defining moment of our collective existence is certainly the Kosovo tradition. It revolves around the consequences of the Battle of Kosovo in 1389. This battle, which took place on the Kosovo field near Priština, embodied the historical conflict between the Ottoman imperial army and Serbian medieval armies under the command of Prince Lazar. This militarily indecisive battle—the only one in Ottoman history that resulted in the battlefield death of a sultan—exhausted the forces of both the Serbian medieval state and its autochthonous nobility. Thus, the consequences of this battle were easily understood—in both oral and written testimonials—as precipitating the end of independent Serbian statehood to the Ottoman Empire in 1459.

The Kosovo tradition represents a historical verticality of both the spiritual and historical destiny of the Serbian nation, for it instilled the feeling that “established our fourteenth-century national tragedy as the predominant spiritual substance of the nation in the centuries that followed,” in the words of historian Anica Savić-Rebac. In its sublime and representative forms—both in the works of medieval writers and Serbian epic poetry, as well as in the writings of great talents like the classic poet of Serbian culture, Montenegro’s Prince-Bishop Petar II Petrović Njegoš—this literary tradition shaped a “specifically Serbian feeling of auto-tragedy,” as Savić-Rebac has put it. It characteristically appears in the two representative forms of medieval culture.

We find medieval texts about Kosovo as a particular feeling of the world that has both a vertical and a horizontal dimension. The horizontal one determines a person in time; the vertical dimension determines a person in spirit. The tradition of Kosovo—sealed with Lazar’s covenant—evolved in both directions. Lazar’s choice, as something that embodies the Kosovo covenant, is about opting for the eternal, heavenly kingdom over holding onto an earthly one. This choice, which oral tradition tells us was made prior to the battle, points to something often overlooked with respect to the Kosovo covenant: Lazar did not avoid fighting the Ottomans. After choosing the heavenly kingdom, he went into battle, nonetheless. This shows that the Kosovo covenant does not imply a passive acceptance of the inevitable. Rather, it demonstrates the existence of an active or dynamic agent: Lazar is characterized by an inner stratification representing a Christian moment of freedom that justifies his confidence in the promise of the Kingdom of Heaven: “we die with Christ to live forever,” the epic tradition tells us he exclaimed to his soldiers as they took communion before taking to the battlefield.

Migrations

The third important element of Serbian cultural identity is related to the historical destiny of the Serbian nation at the turn of the epochs, that is, during the transition from the medieval period to early modern times. It prompted migrations from south to north and from east to west. In the Balkans, migrations were neither rare nor limited to the Serbs. Jovan Cvijić, a Serbian anthropogeographer writing in the early twentieth century, termed these “metanastasic movements.” These migrations, he said, represented a historical process lasting centuries—one that culminated for us in the Great Migration of the Serbs under Patriarch Arsenije III Čarnojević. In 1690, fearing Ottoman vengeance, he left his seat in Peć, located in the heart of Metohija, and led a mass exodus of Serbs into the Habsburg Empire at the invitation of Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I.

The situation in the new land was not easy for the Orthodox Serbs. They were subjected to great and constant pressure from an aggressive form of Catholicism. The Primate of Hungary and a leading Counter-Reformation figure in Central Europe, Cardinal Leopold Karl von Kollonitsch, wrote to the Habsburg emperor that the Serbs should not be allowed to remain Orthodox—not only for religious (Catholic) reasons but also because it was in the interest of the empire. This historical assessment has ominously accompanied the destiny of the Serbian nation through to most recent times. The cardinal’s assessment represented a dual historical condemnation: a new wave of migration took parts of the Serbian nation to the territory of the Russian empire.

The greatest Serbian historical novel—Miloš Crnjanski’s Migrations (1929)—artistically depicted this dimension of national existence. Crnjanski made it universal by tying it to antiquity(Odyssean journey), Christianity (chosenness),and modernity: a national experience interpreted as a constant of humanity, both in its tragic and ironical contexts. All the more reason for interpreting the title of Crnjanski’s novel Migrations as bearing the name of our collective national destiny.

Overlapping of Experiences

All this has enabled the shaping of different models of Serbian culture, which has significantly determined the character of Serbian culture in toto, because the cultural form of the existence of the Serbian nation itself began to change and complement itself. An artistic contact between Byzantine (Orthodox) and Central European (Catholic) traditions took place. At the same time, within this historical development, elements of Islamic tradition also

penetrated Serbian culture. Therefore, we have a crossover in the conception of Serbian culture, which has only increased over time. If we consider Vuk Karadžić’s Serbian Dictionary as the representative work of this decisive reformer of the Serbian language—his work enjoyed the support of Goethe, the Brothers Grimm, and leading philologists of his time—then we discover that around 20 percent of the entries contained in its first edition (1818) were Turkish loanwords, many of which were actually derived from Persian. This means that Islamic culture left its mark during its centuries-long presence.

This three-component cultural existence—introduced by migrations to the north and the west—left its traces on both historical and artistic monuments. These traces marked national identity as a dynamic category—not a static one. National identity changes in time without succumbing entirely to time. It endures the coercive power of history, symbolically reshaping it and transforming it into the contents of collective self-understanding.

The overlapping of experiences is a characteristic component of every culture. Indeed, the overlapping of experiences that appeared in Serbian culture has significantly determined its character. Did this represent a break with the Kosovo tradition or the Saint Sava tradition?

One of the most beautiful buildings in Trieste—a city that perhaps represents the westernmost point of our collective migration—is Spiridon Gopčević’s famous palazzo, completed in 1850. With its wave-shaped façade, the building seems to emulate the movement of the sea, located in its vicinity.

How did it appear there?

A small colony of Serbian merchants settled in Trieste in the eighteenth century, when the city came under Austrian rule and became a privileged seaport. The colony in question became very influential and gained considerable wealth through its trading ventures. One of their most prominent descendants was Spiridon Gopčević, who belonged to the third generation of Serbs living in Trieste. It was this highly educated man—a prosperous ship owner and merchant who also corresponded with political figures as varied as Giuseppe Garibaldi and William Gladstone—who built this incredible building in the heart of a very Catholic city. According to one Italian historian’s account, “the presence of numerous statues and medallions on the building façade is really unique and unusual, as if it is some kind of manifesto. They depict the tragic Serbian epic about the Battle of Kosovo, which had a decisive impact on the history of the Serbian nation.” The battle itself was characteristically embodied in stone: “The statue group depicts four main protagonists of the battle: Prince Lazar and Princess Milica are on the left and Duke Miloš Obilić and the ‘Kosovo Maiden’ on the right side of the entrance,” the same account informs us.

In an entirely different environment compared to the one his ancestors had left—an environment with whose demands he himself had to comply—Spiridon Gopčević did not want to renounce the tradition that had shaped both his personal and his collective, symbolic self-understanding: the tradition of Kosovo. At a moment when his personal existence had been reduced to its most basic formulas, he reached for a collective, national identity point that represented the tradition of Kosovo.

That moment is of utmost importance. It demonstrates how right Vuk had been in his explanation of why our oral epics contained with so few pre-Kosovo narratives: the change brought about by the entry into national consciousness of the Kosovo disaster had such a tremendous impact that it overlaid and blocked out memories of previous events.

The Nation-state

The fourth component of the cultural pattern of the Serbian nation is tied to the secular experience of the new century. This had an impact on those Serbs living, since the Middle Ages, north of the Sava and Danube, and west of the Drina, all the way to the eastern coast of the Adriatic Sea—as evidenced by untold numbers of toponyms, monuments, and monasteries.

However, when these Serbs appeared before the astonished eyes of the world of Central Europe—at Leopold I’s invitation, and having been granted unique privileges due to their specificity—they were recognized not only as a nation seeking refuge from the Ottoman invaders in 1690, but also as a self-conscious and self-aware nation. This is when the Serbian nation stepped onto the modern historical stage, encountering the Baroque world that had come to them first along the winding road of Russo-Slavic influence but that had really come into its own in the Catholic surroundings of Central Europe in which they found themselves. These Serbs came into contact with the ideas of the Enlightenment, which took on the characteristics of both bourgeois Enlightenment (Zaharije Orfelin) and religious Enlightenment (Jovan Rajić), thanks to the development of urban social classes made up of craftsmen and tradesmen, enriched by various cultural institutions, the establishment of a new military nobility, and encompassing elements of both petite and haute bourgeoisies.

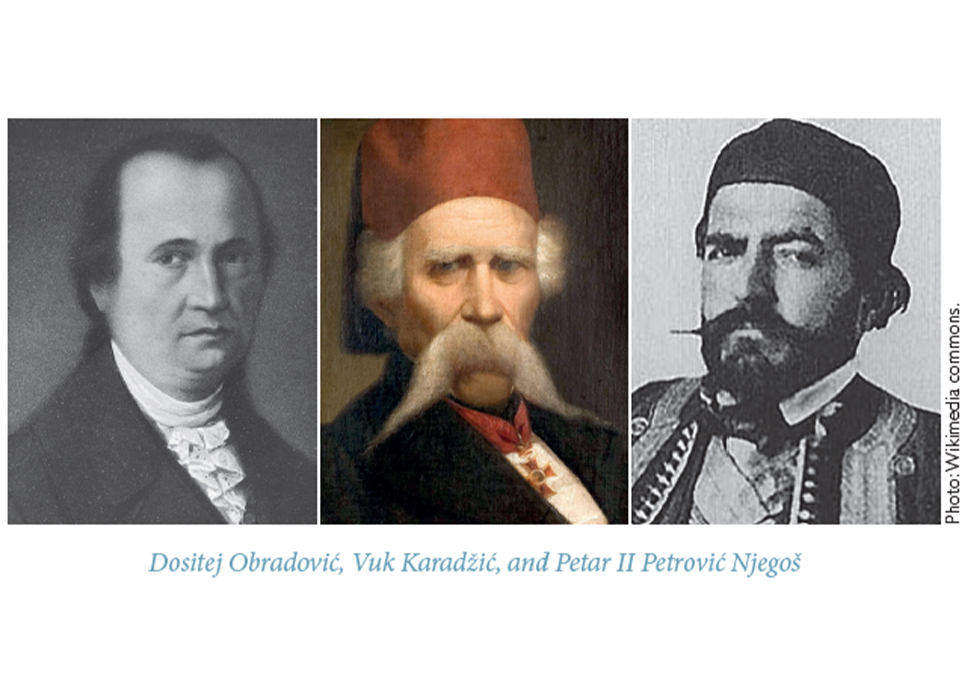

The idea of a nation-state—which emerged for the Serbs in parallel to the European development of this concept in the early nineteenth century, and to which the most important impetus was given by the French Revolution—was fully adjusted to contemporary rhythms: it represents the fourth component of the Serbian cultural pattern. Heavily relying on the rise of secularism in the 18th and 19th centuries throughout the Old Continent, this component had a distinctly secular character. It was personified by Dositej Obradović, who brought the spirit of the Enlightenment into our cultural horizon. Having abandoned a monastic life, Dositej went on to follow a roadmap to the Protestant universities of Halle and Leipzig, lived in Vienna and Trieste, visited Paris and London, and wrote a refined version of the vernacular. He criticized the church and its institutions in the manner of Voltaire, penned a literary autobiography in the spirit of the Enlightenment, and as a model modern citizen took part in the first-ever uprising that any nation living under the Ottoman yoke in Southeast Europe had ever launched (and successfully executed). That is when the Serbian peasantry came to lay the foundation of the modern Serbian nation-state.

The establishment of the Serbian nation-state spearheaded a movement that did not imply the annulment of either the tradition of Saint Sava or Kosovo. Vuk and Njegoš laid the cultural foundations for an education in the national culture: the Kosovo tradition was always given a privileged place in their works. This is what Serbian statesmen also felt: regardless of whether they were conservatives of national liberals, Russophiles or Westerners, they all shared a political view that most often rose above political particularism and was oriented towards that which leads to the whole.

They understood that in the new (secular) era, Saint Sava’s sacral function could not be introduced into secular state institutions. So they emphasized the enlightening aspect of Saint Sava’s personality and brought it into the newly-emerging school system. This represents an extraordinary example of how a central moment of an identity can be adjusted to the dictates of time so that it is not lost to time but rather preserved in time. This shows that Serbian cultural existence had the ability to assimilate and amalgamate different traditions. Here it should be noted that a discontinuity with the Saint Sava tradition was only achieved by the communist dictatorship in the years following their seizure of power in 1945. During this period, Saint Sava was erased from the public form of our collective existence.

In 1918, Serbia was the only South Slavic state that was on the side of the victors. At the same time, it had a very clearly formulated national idea: the unification of the Serbian nation. We also had a very strongly formulated idea of the state, personified by two independent states: Serbia and Montenegro. And we also had a strongly confirmed military idea, having demonstrated the victorious character of the Serbian Army in both Balkan Wars and World War I. What was necessary—and to a certain extent was lacking—was a cultural idea. By this I mean the idea of a unique cultural framework that would bring together different traditions of Serbian national and cultural existence: Byzantine-Orthodox, Central European, and secular models. At the same time, it was necessary to culturally connect very diverse regional consciousnesses within one Serbian national existence.

Before the establishment of Yugoslavia, a Central European (Austro-German) cultural model existed to the north of the Sava and the Danube. A French cultural model, centered on Belgrade, was dominant in southern intellectual circles and was characterized by the established norms of the Serbian cultural and literary language and style, as well as by the newly-endowed University of Belgrade.

Why were both spiritually connected to the French cultural model?

Because the Catholic-Germanic threat, embodied by the Habsburg empire, was a life-threatening one. Hence a model was sought that would lessen this threat, not heighten it. And also because the prevailing opinion around the turn of the twentieth century was that the democratic principle was the principle of the future. Thus, the democratic ideal largely conditioned the adoption of the French cultural model in our public consciousness in the period before the onset of World War I.

Yugoslavia

The existence of different cultural models can undoubtedly help us understand the cause of a certain degree of rivalry with respect to opting for one or another tradition; it can even help explain the polycentric development of Serbian culture. But it cannot be a distinctive fact when it comes to our actual cultural and national existence. Hence it follows that no polycentricity can be translated into a nationally distinctive fact, because such a cultural pattern needs to match our different traditions and neutralize different regional and particular aspirations.

So why did this not happen?

The reason lies in the fact that the creation of the Yugoslav cultural pattern in 1918 began at a time when the Serbian cultural pattern had not yet been crystallized, consolidated, and entrenched. Our most prominent historian and legal scholar Slobodan Jovanović later wrote something about this arrested development in his old age, living in exile in post-World War II London. He said that with the establishment of Yugoslavia, the Serbs carried out their “national demobilization.” This assessment is of great importance because it shows that the movement towards the formation of national identity had not been completed.

In parallel with such a movement, the Russian influence in our country underwent an important change. In the twentieth century, there were two aspects to this problem. Namely, in the interwar period, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes had a distinctly anti-Soviet stance. This was due to at least three reasons: adherence to the monarchist principle; the immigration of a large number of White Russians and their high reputation and influence, especially in Serbia; and the Comintern’s policies, which had adopted the view of Austro-Marxists with respect to the ‘perils of Greater Serbian hegemony’ and thus embraced the position that Yugoslavia was an artificial creation that had to be destroyed.

In that anti-Soviet stance, however, there were no elements of Russophobia. It consisted, rather, of the state’s caution and anxiety over the possibility that the Western powers might not look favorably upon a hypothetical rapprochement with Soviet Russia. Namely, as early as 1914, Prince Regent Alexander Karadjordjević guaranteed that Serbia did not intend to become a Russian province, as evidenced from a memorandum written by R.W. Seton-Watson (irrespective of the fact that our state did not share a border with Russia).

After communist Yugoslavia’s break with the Cominform in 1948, there followed a very subtle and elaborate accumulation of American and Western influences that went on for decades. At the same time, an a priori distrustful attitude toward any Soviet presence was developed. Thus, for example, were citizens of Yugoslavia awarded the largest number of Fulbright fellowships during the Cold War era (even ahead of West Germany)—a fact we can find in the writings of historian John Lampe. So not France, not Italy: countries with much larger populations than Yugoslavia. Due to intense Western (American) indoctrination, which took place within the larger framework of Cold War propaganda efforts, a tense and negative attitude towards the communist tradition was semantically transferred to Soviet Russia’s presence and influence.

With respect to the degree of Russian influence, we can observe certain movements in specified periods over the centuries. In the eighteenth century, the Russian cultural presence was very strong: through the use of a more or less common liturgical language, an emphasis on various forms of pan-Slavism (or Slavic solidarity), Baroque-style painting and architecture, and the use of sacerdotal vessels and vials in churches and monasteries. Our eighteenth-century political leaders were most often church dignitaries, and they were also oriented towards Russian traditions. A striking example of this last is a 1705 letter written by Patriarch Arsenije III Čarnojević to Count Feodor Golovin, the first Chancellor of the Russian Empire; or the petitions signed by prominent Serbs sent to Peter the Great to help secure the release Count Djordje Branković—the author of the first political manifesto among the Serbs—who was placed under house arrest in the Hapsburg lands. There exists, therefore, a parallelism in our cultural and political orientation in the eighteenth century.

In the nineteenth century, the political orientation that followed Russian interests was important, because that era was Russia’s great century in terms of historical momentum. Consider an episode that took place during a critical gathering of Serbian notables at the Vraćevšnica monastery in 1810 during the First Serbian Uprising. On this occasion, Dositej, our greatest Westernizer in the cultural field, suggested that we align with Russia and not Austria, because he realistically assessed the assistance to the war effort provided to Karadjordje’s Serbia by both St. Petersburg and Vienna. Here we observe a certain duality: our cultural background was becoming increasingly Westernized, while our political orientation, albeit meandering, remained in a relationship of obligation towards Russia. This took place gradually: most of our intellectuals studied in Vienna and Paris, so that they were even divided into Viennese and Parisian camps, as it were. A smaller number of them also studied in Berlin, Jena, and St. Petersburg.

At the end of the nineteenth century we had a cultural foundation that was essentially Western: most of our intellectuals looked in the direction of the West, influenced most notably by France due to the republican, democratic, and secularist ideas it professed. This was not without reason: the Western world seemed attractive to those endowed with critical means to make, say, political assessments. The trouble was that—as Slobodan Jovanović admitted later in his life—such people looked at the Western world without any critical distance, almost idolatrously. Throughout the twentieth century, our cultural and intellectual establishment was deeply filled with Western (American) influences, whereas the Russian cultural influence was in retreat—although some Russian political influence was felt in certain periods.

Thus, we can observe that over a period of three centuries a gradual change in the content of our cultural framework brought about a significant change in the content of our politics.

Victory and Collapse

These facts had a far-reaching impact: they appeared before our eyes from the moment Yugoslavia collapsed in 1991. We should not, however, confuse the coming to power of Yugoslav communists in 1945 with the support on which the Titoist regime rested. As a direct consequence of the Soviet Union’s military victory in World War II, communist regimes seized power in many East-Central European countries; but it was only the Yugoslav communist regime that managed to break successfully with the Soviet Union after only a few years. This did not prevent it from remaining both totalitarian and dictatorial, however.

Present-day Russia’s attempt to preserve the symbolic significance of the Red Army’s victory in World War II meant that Moscow continues to give preference—in the context of furthering the culture of remembrance—to the coming of the communists to power in our country and contributes to the downplaying of the precise historical consciousness of the other antifascist movement led by General Draža Mihailović’s Chetniks.

Guided by its interests and being imperially insensitive, contemporary Russian politics refuses to understand that, in the history of the Serbian nation, the year 1945 is comparable to the year 1918 in the history of the Russian nation: their communist revolution resulted in the loss of monarchy, introduced an internal reign of terror, produced violent acts of denationalization, stripped it of territories recognized in the aftermaths of previous wars, significantly reduced the depth of its cultural heritage, and both materially and morally devasted its Orthodox Church. Something similar could be said of the Serbian nation’s situation starting in 1945. In short, the respective actions of new regimes ruling over the two nations (the Serbian in 1945 and the Russian in 1918) transformed each from a victor into a defeated victim.

On the other hand, the Serbian triumph of 1918 is comparable to the Soviet one of 1945: each achieved a great victory after an almost unimaginable sacrifice. In the case of the former, the result produced the integration of the Serbian state into a broader Yugoslav one that extended into Central Europe; in the case of the latter, it moved both the de jure and de facto borders of Soviet Union westward—also into Central Europe. Both entered into broader constellations of relations and territories—and both saw their power and influence increase.

And in both cases, the disastrous consequences of all this became evident only decades later: in the years immediately following the fall of the Berlin Wall. This is when both Yugoslavia and Soviet Union vanished. And then—as if they both experienced some sort of awakening or the overcoming of an epochal interregnum—the traditions, history, and politics of Serbia and Russia met once again in real time. Still here it must be noted that because of the inherited predestine propaganda of the Soviet view of things, contemporary Russian politics does not wish to observe the epochal inversion of the positions of the Serbian and Russian nations in the twentieth century. History does not unfold only linearly with time; in the context of the culture of remembrance, one comes also to recognize the circular movement of events and processes.

Jasenovac

In the Yugoslav experience itself we can recognize two moments. There is the inter-war Yugoslav experience which, according to foreign cultural historians like Andrew Wachtel, aspired in many ways toward integration—a form of multiculturalism. And then there is the post-World War II Yugoslav experience, which developed national cultural concepts that in the 1980s took on a form that precipitated the cultural disintegration of Yugoslavia.

It is important to understand that the manner in which the communists ruled has prevented sufficient light to be shed on one historical event that played out in the twentieth century in both cultural and symbolic terms. In the past century, the Serbian nation suffered a genocide. In its centuries-old historical movement between two worlds (Orthodox and Catholic) and two empires (Ottoman and Habsburg), there is nothing in the history of the Serbian nation that can be compared to the events symbolized by an invocation of the name Jasenovac. Although the murder of untold numbers of innocent Serbs took place at various sites located throughout the territories controlled by the evil regime known as the Independent State of Croatia, its symbolic nucleus is the Jasenovac concentration camp.

This is a fact that demands the greatest possible attention. One cannot move beyond it—at least without grave consequence—with one’s eyes closed. The Armenian nation, which suffered a genocide in World War I, and the Jewish nation, which suffered a genocide in World War II, are those we need most to emulate, within the scope of a deeper collective understanding of historical destiny.

When we consider the great artistic achievements of writers like Crnjanski and Ivo Andrić, or of painters like Petar Lubarda and Sava Šumanović, our twentieth century experience is rightfully characterized as being in ascendance. But in the processes of shaping Serbian cultural identity it was a time of decline and reversal.

The question that goes to the very heart of the matter is this: in the process of creating a singular Serbian cultural policy, how can we conserve the unquestionable polycentricity of Serbian culture?

The history of the Serbian nation points to its polycentricity in different historical periods. In some periods, when the Serbian state did not exist, certain cities—like Vienna (Austria), Trieste (Italy), Novi Sad (Serbia),or Mostar (Bosnia and Herzegovina)—played the role of cultural centers for the Serbian nation, as did Cetinje (Montenegro) in the past. This polycentricity unquestionably still exists because Serbian culture is culture of contact. However, this sort of experience of polycentricity can have both positive and negative aspects. It depends on how a cultural pattern is shaped. The absence of a Serbian cultural pattern has, over time, hyper-atrophied our polycentricity, reducing our cultural roadmap to what amounts to disintegrative movements.

What then does the Serbian cultural pattern mean? In a way it means the establishment of a public consciousness about the whole. And it means the establishment of a genuine content to our national consciousness itself, regardless of whether it captures the past or describes the present. A consciousness of the Serbian nation as a whole—as a public consciousness—implies a type of behavior that includes a positive view of polycentricity. Polycentricity as a natural existence of a culture and a nation in various contacts is one thing; its political instrumentalization is quite another. These two facts must always be kept in mind, because it would be neither reasonable nor possible to expect polycentricity to be nullified. From the choice of cultural pattern will depend which tendency shall prevail in the time ahead.