Professor Anatoly V. Torkunov is the Rector of the Moscow State Institute of International Relations (MGIMO), a position he has held since 1992. He is a full member of the Presidium of the Russian Academy of Sciences and a member of the Board of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Professor Anatoly V. Torkunov is the Rector of the Moscow State Institute of International Relations (MGIMO), a position he has held since 1992. He is a full member of the Presidium of the Russian Academy of Sciences and a member of the Board of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Starting from the late 1980s when the sustainable development concept was formalized, the history of its implementation has resembled a swing for quite a long time. The spells of enthusiasm with buoyant and efficient activity, were often followed by years of disappointment and quiescence. The year 2015, which saw the adoption of the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Paris Climate Agreement of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), became a turning point. Sustainable development has been put to the fore in declarations of the world’s major economies and other institutions of global governance. It has extended to ministerial and industry levels of international collaboration, and the focus on sustainable development has become an essential condition for transborder economic activities. Neither escalating security challenges, right-wing populist pivots of certain global economies (perhaps most notably exemplified by former President Donald Trump’s four years in office in the United States), nor the shock of the COVID-19 pandemic have significantly influenced this trend.

However, inspiration is never the only key to success, and the world is currently viewing its near future and the advances set by the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development with considerable skepticism.

According to model forecasts made in 2021 by a large group of scholars (V. Soergel, E. Kriegler, I. Weindl, S. Rauner, A. Dirnaichner et al.)—considering the existing development trajectory and due to systemic inertia—we are presently not on the path to fully achieving any of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), even by the middle of the century.

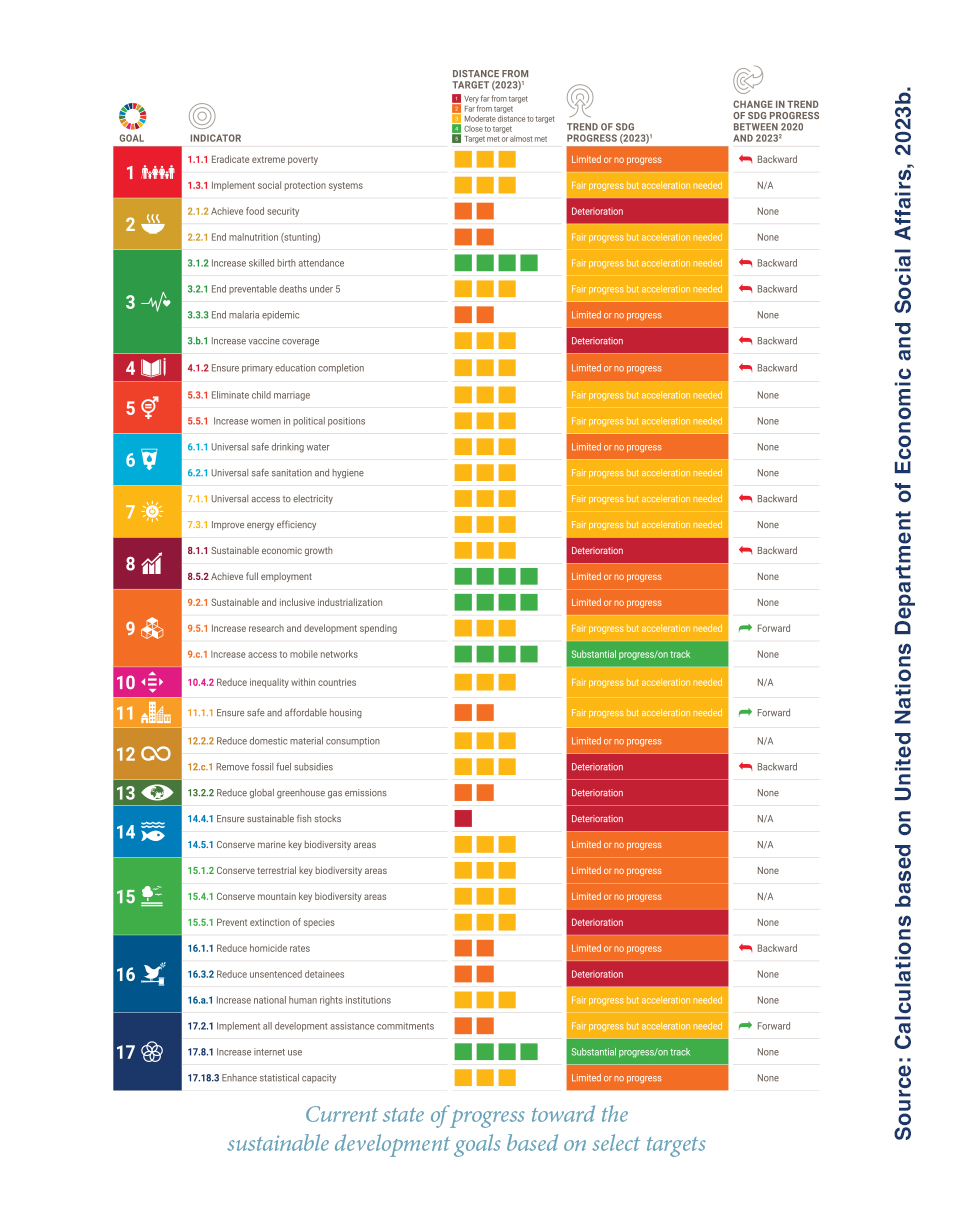

These estimates were confirmed by the 2023 ‘Global Report on Sustainable Development’ published by the UN Department on Economic and Social Affairs in November 2023. The UN experts argue that halfway to 2030, the situation is ‘much harder’ relative to the late 2010s. The SDGs that can currently be characterized as ‘being within reach of their attainment’ are a rare exception. Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a trend towards deterioration referring to many SDGs over the period between 2020 and 2023. The eradication of extreme poverty demonstrates much lower rates than before (the top position in the industry-related goals list made in 2015). Considerable deceleration of the process has been observed in many other targets: GDP; subsidizing the fossil fuel industry; access to energy services; quality obstetrics; mortality of children up to five years of age; vaccine coverage; lower homicide rate. Only a few SDGs have demonstrated some progress since 2019, however, several of the SDGs are evidently regressing. The recent ‘gloomy’ list includes, inter alia, achieving food security, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and fighting biodiversity loss. Since the adoption of the SGDs, the number of people experiencing hunger or lack of food security has been growing incrementally.

The emergence of the aforementioned document was prefaced by a preparatory report by a group of independent scholars from various countries (including Russia), assembled by the UN Secretary-General. Written in an ‘opinion piece’ style, the report provides a bright description of the situation, including many actual examples and data.

The report’s bottom line was basically similar: “Today, when we are half-way to meeting deadlines set by 2030 Agenda, we must admit the following disillusioning real fact: the world is behind schedule referring to most SDGs achievement by 2030. There is certain progress in some spheres, however, the progress towards an alarmingly large number of targets is either too slow, or even has given way to regression.”

National statistics are not always capable of tracking the real state or pace of change. In those places where they have been successful, the situation around the midpoint of 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development is as follows: performance is on schedule when it comes to 16 percent of the targets, almost half the targets lag far or moderately behind, whereas 37 percent of the targets demonstrate stagnation or regression below the 2015 baseline. While the first third of the 2030 Agenda’s implementation trajectory made observers optimistic, then “at present it has become evident that the major portion of these developments was unstable and the progress rate in many spheres was too low.”

In contrast to this, hunger and poverty levels remain stubbornly stable. Maternal mortality rates have not been reduced. In 2021, the world saw the largest number of intentional homicides over the recent two decades.

Yet, the global “progress” in education is to result in the fact that by the end of the ongoing decade only every sixth country will address the task of all children obtaining secondary education. About 84 million children of school age will not attend schools, while 300 million will finish their education without acquiring basic numeracy and literacy skills.

Though one cannot deny some advances of recent conferences within the UNFCCC—Paris (2015), Glasgow (2021), and Dubai (2023)—which gives ground for cautious optimism, they have not managed to turn around the global degrading trend in this sphere. Carbon dioxide concentration is rising, humanity is getting closer to the 1.5 °C warming threshold, as stipulated by the Paris Agreement.

At current progress rates, in 2030, the renewable energy sources will account for just a small fraction of energy supply, with approximately 600 million people potentially living without electricity and almost 2 billion continuing domestic use of unsustainable types of fuel and food technology. Neither deforestation nor significant biodiversity loss will be halted by the expected deadline.

The current state of progress towards the sustainable development goals based on selected targets:

However, the targets will definitely remain far beneath the intended results if basic principles of global development do not change. The UN experts have to admit that while the lack of success in the implementation progress of the 2030 Agenda is noted by many, it is “absolutely evident that the main consequential burden of such collective failure will lie heavily on developing countries and on the poorest and most vulnerable groups of the world population. This is a direct consequence of global inequity which emerged hundreds of years ago, however, has not been eradicated so far.”

In high-income countries, material footprint per capita is dozens of times higher than in the emerging economies. Should the current trends hold, 7 percent of the world population (or around 575 million people) will live in extreme poverty by the end of the decade, with most of these people living in Sub-Saharan Africa. This kind of result will imply minimal reduction in poverty over the last decade and a half—less than 30 percent. The Global South will remain the Global South not only within the Dark Continent. Of the 127 countries for which data is available, only one third will be able to halve their national poverty levels by 2030.

The number of people facing hunger and lack of food security is growing, “with the situation being aggravated by the pandemic, conflicts, climate change and growing inequality.” In 2022, around 735 million people—almost one tenth of the planet’s population—experienced chronic hunger, which is 122 million less than three years ago. The portion of the malnourished in the world has relapsed to levels last seen in 2005—with food prices in most countries being much higher now than in the late 2010s. The category of those who face moderate or acute shortage of food amounts to 2.4 billion people, slightly less than one third of the Earth’s population, which has increased by 391 million since 2019.

According to experts, ensuring universal access to clean water, sanitation services, and hygiene products by 2030 will require a considerable acceleration of existing progress rates—more specifically, three- to six-fold. As for SDG11 ‘Sustainable cities’: almost 1.1 billion people reside in slums or similar types of accommodation at the moment, whereas this figure is only set to grow by 2 more billion over the next three decades.

The year 2022 saw the largest number of refugees on record (34.6 million people). These forced migrants accounted for a total number of 108.4 million people, which is a 17.5 percent increase from the previous year and 2.5-fold rise relative to the last decade.

The reasons for failure and disproportion on the path towards achieving the SDGs are many. However, one of the main reasons is evident: the critical state of international financing for further development. “The gap between our intentions to develop and existing funds allocated to satisfy these requirements has never been larger,” UN experts argue. The deficiency of funds needed to accomplish the SDGs is estimated to reach trillions of dollars.

Some of this is attributable to the archaic state of the Bretton Woods system. However, such archaism is still difficult to fight, which is compounded by the lack of will on part of the major economies to finance development processes. The structure of the global economy itself, in the form in which it presently exists, resists the establishment of any effective form of international financial aid.

Presented by the UN Department on Social and Economic Affairs in April 2024, “Financing for Sustainable Development Report 2024” notes that “after success of fighting global financial economic crisis of 2008, certain international bodies setting standards have recently faced stalling or reduced level of presentation of developing countries in their major policymaking institutions.” The IMF’s 16th general quota review, completed in late 2023, was closed without any agreement regarding the redistribution of voting shares.

According to various estimations, at present, the growing annual financial deficit makes up somewhere between $2.5 and $4 trillion. A more detailed description of the situation is as follows: emerging economies are facing a considerable reduction in access to long-term and contingency financing. With present high interest rates, sovereign spreads have become particularly high for issuers from developing countries, which increases their dependence on concessional resources to reduce global financial costs.

The expected interest rate on sovereign debt of least developed and middle-income countries is, on average, more than twice as high as the interest rate of wealthy countries. This is a result of domestic factors as well as decreased capital flows into underdeveloped countries.

This is also expressed in the higher cost of capital for private investors. For instance, as per estimates, capital costs of comparable projects in the renewable energy sector in developing counties exceed those in developed countries by two to three times, whereas risk premiums are more likely to be defined by macroeconomic risks rather than the risks related to a particular project.

More than half of the least developed counties are either on the verge of a severe debt crisis or have already entered such cycles. Twenty-five emerging economies allocate more than one fifth of their total revenues for foreign debt service only. Around 3.3 billion people live in countries where the authorities tend to spend more on debt interest than on education or healthcare.

In June 2024, noting a low level of expenditures on green energy in the emerging economies (excluding China and including India and Brazil), the International Energy Agency (IEA) provided a vivid illustration of sustainable development stalling in the Global South due to the high price of foreign funding. Although, according to the IEA forecast, their investments in 2024 might exceed $300 billion, this figure will make up for just about 15 percent of the global indicators. “This level is much below what is required to satisfy the growing demand for energy in many of these countries, where high costs of raising finance constrain new projects development.”

At the same time, the IEA expects Chinese investments into clean energy in 2024 to reach $675 billion, with European investments reaching $370 billion and those of the United States amounting to $315 billion.

Overall, such a critical situation with funding is clearly reflected in international environmental financing, which has long been in the public focus due to the performance of the UNFCCC and independent global bodies. However, this focus, while accompanied by millions of right words and thousands of reasonable ideas, has not yet brought much progress.

In late May 2024, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), claimed that the goal of annual financing for efforts to battle climate change was finally reached (and exceeded)—estimated at $100 billion. This commitment was already made at the 2009 Copenhagen Conference. The year 2020 was initially planned as the first year of its implementation. The OECD preliminarily reported such an achievement in 2023 already. However, contrary to the expectations of the West, they failed to include it in the “Global Summary” of COP28 in Dubai, obviously due to insufficient financing.

All these facts are explicitly pointed out in the OECD report. The allocated funds are mostly expensive, and the world is still far from balancing the funds allocated for the mitigation of consequences (i.e. decarbonization) and adapting to them (i.e. addressing economic and social problems caused by climate change)—a goal stipulated in the FCCC documents.

According to OECD estimates, the share of adaptive projects reached 28 percent in 2022, an increase of $22.3 billion compared to the previous six years. However, the funding allocated for the mitigation of consequences still amounts to more than twice that sum, representing 60 percent of the total volume, with a growth of $27.7 billion over a similar period.

Declarations at UNFCCC conferences also stipulate the need for grant financing or concessional financing. Yet, the OECD recognizes that in 2022, and over the years prior, state environmental financing of developed countries—provided both bilaterally and multilaterally—mainly took the form of loans (69 percent or $63.6 billion). The portion of grants turned out to be considerably lower: 28 percent or $25.6 billion. From 2016 to 2022, the annual volume of grants increased by $13.4 billion (109 percent), while the level of government loans grew by $30.3 billion (91 percent). As for the funds allocated by international development banks, 90 percent of these funds were loans.

Such a ratio is directly related to the imbalance regarding ‘consequences mitigation/adaptation.’ In the period between 2016 and 2022, a major share of adaptation measures (38 percent) and cross-sectoral financing (55 percent) was grant-derived. Loans, as a rule, are spent on the mitigation of consequences (where one can reasonably speak about profits), whereas grants make up just 15 percent.

The third trajectory of environmental finance, which has received its appropriate instrument only recently, is compensation for losses and damage. For a long time, the United States and its allies found the “losses and damages” wording completely unacceptable, fearing it could provoke legal claims against ‘classic’ polluters, i.e. the largest Western powers.

Yet, the claimed payments by developed countries into the Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage, established at COP28, amounted to only $661.4 million, according to data provided at the first meeting of the Fund’s Managing Council on April 12th, 2024. This level of capitalization is evidently not enough for the percentage of actual losses and damage already inflicted (or expected in the near future). According to the 2023 Climate Finance Shadow Report released by the international charity network Oxfam, by the end of this decade, the only economic expenditures in this sphere will range between $447 and $894 billion annually. This does not account for non-economic losses, such as the loss of cultural heritage.

Conventionality and relativism of the $100 billion goal is a recurring theme of Oxfam’s ‘Shadow Report.’ The document’s bottom line was quite eloquent: “Achieving the goal on paper is not enough as both the way climate change funding is provided and the amount in which it is provided, matter. The report shows how excessive loans, insufficient grants and inappropriate finance of adaptation and misleading accounting principles lead to environmental financing being far from reaching its goal…The worst thing is that in some cases, this funding, which is to ensure communities well-being, inflicts damage in other ways, increasing debt and reducing the official stimulus meant for further development.”

Amid actual and ever-growing needs, the 100 billion-indicator by itself looks extremely modest. As per various estimates, by 2030, the implementation of measures reflected in nationally defined contributions—a major instrument of Paris Agreement implementation by member countries—will require between $5 and $14 billion. The UN Conference on Trade and Development assessed the level of foreign investments necessary by 2030 to fight climate change as $1.55 trillion.

The Independent high level expert group on environmental financing (IHLEG) assumes that by 2030, developing countries, with the exception of China, will require investments valued at $2.4 trillion a year to achieve the goals in the climate and environment sphere. This is four times more than their current investment level. IHLEG experts believe that international fundraising sources will be necessary to acquire approximately $1 trillion out of the sum required.

Climate inequality is demonstrated not only along the borderline between the Global North and Global South. “The Super-Rich are Burning our World,” was the headline of another recent report by Oxfam. “Climate Equality: A Planet for the 99 percent,” the report read in November 2023.

The thesis was substantially supported by statistics. In 2019, 1 percent of the super-rich people on our planet was responsible for 16 percent of global carbon dioxide emissions, which is equivalent to 66 percent of the emissions of the world’s poorest population (5 billion people). Since the UNFCCC was adopted, 1 percent of the super-rich have spent twice the amount of the carbon budget compared to the poorest half of humanity combined. Annual global emissions of the super-rich offset all the CO2 savings provided by almost a million inland wind turbines. The emissions of the super-rich were enough to result in 1.3 million deaths due to heat.

The report shows an infographic of the torch burning the world: a large bowl of which 50 percent is taken up by greenhouse gas emissions for which 10 percent of the wealthy people are responsible. Just below it is a tapered base: 40 percent of the population in the middle-income category and their 42 percent of emissions. Further, there is a very narrow stand: the poorest 50 percent, who are responsible for only 8 percent of emissions.

Here is the finding the authors made based on this information: ‘Higher equality will allow us to attain poverty eradication goals and ensure the planet’s survival.’ They refer to World Bank research data: if all existing egregious inequality could be overcome, the carbon dioxide emissions necessary for eradicating extreme poverty would amount to one third of the current indicators, considering existing income inequality.

“Radically fostering equality and redistributing income and wealth,” Oxfam experts argue, “we will ensure everyone has a decent life, simultaneously keeping the planet within the bounds necessary for its survival and prosperity.” The experts do not specify whether such assurances of efficient climate action require a social revolution on a global scale. But one should admit that so far, all attempts to solve these tasks evolutionarily have invariably proved futile.

The issues of climate change and environment protection constitute just a part of the sustainable development global agenda. However, throughout the decades, they have remained pivotal, receiving increasing attention in government policies of both great powers and many developing countries—as well as their bilateral and multilateral collaboration. Fostering global climate security and the related ‘green transition’ to low-carbon economy have become a priority.

In the current circumstances, those who were the main beneficiaries of the industrial epoch are now the main beneficiaries of the ‘green transition’—the population of developed countries. They benefit from utilizing both conventional energy sources and products with high carbon footprint coming from emerging economies, as well as from revenues generated by carbon footprint taxation. Per capita anthropogenic load on the environment in countries of the Global South is still significantly lower than in the West. Environmental colonialism, although nominally condemned, oftentimes just takes on new forms.

That being said, whatever progress has been made in the global fight against climate change, it has not reversed the global trend towards aggravating the situation. It is evident that the latter trend will continue for the foreseeable future. Similar trends can be observed regarding the other SDGs. We can already say that we will only partially manage to implement the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development by the expected time. From a global perspective, no SDG will be completely achieved.

The existing global governance institutions, authorities, and organizations of the wealthy world are not demonstrating the willingness to provide sufficient international aid to ensure development, with the level of ‘sustainability’ of the global economy remaining low. Income, race, and ideology of consumption growth take the world beyond the environmental and resource potential of our planet. Humanity is increasingly facing the dramatic problem of being unable to maintain existing consumption patterns for future generations in the rich world. The same can be said about achieving high consumption levels in emerging economies based on the present technological paradigm, traditional economic models, and institutions. This problem objectively emerges from the environmental capacity of the Earth.

At the moment, the limiting nature of consumerism as the main economic driver is evident. We face the task of revising the existing model of consumerist society, taking into consideration underconsumption in the developing world and climate change issues.

Thus, implementing the sustainable development agenda poses a whole variety of problems for the global expert community. In the short run, this involves tackling the issue of shifting the burden of green transition from raw material and energy producers to end-product consumers. In the mid-term, it implies devising a more realistic model of attaining the 17 SDGs by reducing the economic gap between the North and the South and moving towards convergence—i.e. bringing the periphery closer to the center. Over the long term, we need to build social models in which maximizing profit will not be the main driver of progress.

These tasks are currently being considered by a large group of scholars at Moscow State University (MSU) and the Moscow State Institute of International Relations (MGIMO) with the intention of presenting a comprehensive report by the time COP29 takes place in Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan. Similar tasks are now occupying the minds of teams of scholars and scientists all over the world. Efficient accomplishment of the SDGs, both by 2030 and in the longer term, will rely heavily on the successful implementation of these solutions and the level of commitment of the authorities at national and global governance levels.