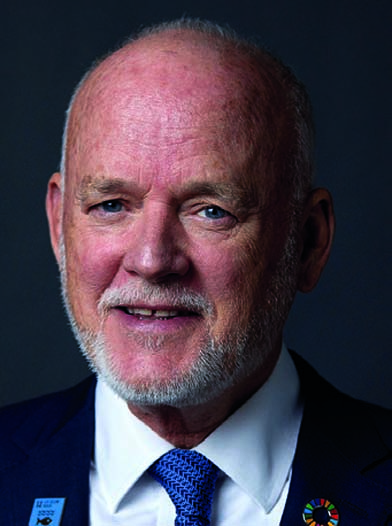

Peter Thomson is the United Nations Secretary-General’s Special Envoy for the Ocean, having previously served as President of the UN General Assembly and Permanent Representative of Fiji to the UN.

Peter Thomson is the United Nations Secretary-General’s Special Envoy for the Ocean, having previously served as President of the UN General Assembly and Permanent Representative of Fiji to the UN.

Empires rise, empires fall. Wars begin and wars end. The tragedies of famine and flood, plague and fire, ebb and flow through the long story of our time on this planet. The ocean too is in ebb and flow, but it is a constant, it is ever the dominant element of this planet. The majesty of the hydrological cycle, the daily evaporation, condensation, precipitation, and storage of water, is the very basis of life. Planet Earth is in fact Planet Water, a planet on which 71 percent of its surface is covered in ocean, on which 95 percent of its possible living space is within the ocean, a planet on which more than half of its oxygen supply is produced in the ocean, with just one little photosynthetic oceanic creature, Prochlorococcus, providing 20 percent of the oxygen in the planet’s biosphere. Without Prochlorococcus, Homo sapiens is not.

Green algae swirling near a beach, a vital ingredient for the future of sustainable agriculture

My hometown is Suva, a port city in Fiji fronted by a massive coral reef and backed by mountain ranges of verdant rainforest. Observing the rituals of the hydrological cycle was an everyday experience at our waterfront school. From out of the south-east, trade-winds would gently disturb the early morning calm of the harbor. Under the heat of the tropical sun, seawater evaporated, condensing in puffy white cumulus clouds in the blue sky above, to drift in flotillas across the bay and crowd up against the mountain ranges. By afternoon, enough was enough, and precipitation would ensue. The word precipitation is hardly sufficient to describe a run-of-the-mill afternoon downpour in the tropics: the crack of lightning, barrages of thunder, and torrents of water crashing down from the sky. Wonderful, in the true sense of the word.

Drenching done, filled with rushing water, creeks and gullies and the drains of the harborside city, returned all that rainwater back to the ocean from whence it had come, all as nature intended. But progressively over the years, with ever-increasing urbanization and the onset of the plastic era, the returning water carried with it the detritus of our streets and throw-away lifestyles: plastic wrappers, bottles, microplastics from our car-tires and house paint, oil residues, chemicals from our factories, cleaning products, fertilizers, the list goes on. This was clearly not what nature intended.

As fate would have it, I was appointed Fiji’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations, arriving there in early 2010 as an ambassador with scant experience in multilateral affairs. It is said that ambassadors at the United Nations, especially those from small countries, have to be jacks-of-all-trades and masters of none. Over the next seven years of service in New York, I found that idiom to be largely true; but I also found there was room to pursue your passions, and for me one of those was the wellbeing of the ocean.

Coming from the South Pacific, I knew that all was not well in the ocean. Being a skindiver, I could see that the big old fish that were plentiful when I was a teenager, were no longer around. Many a favorite coral reef that I knew as a young man as rich bunkers of biodiversity and as underwater gardens of blossoming color and shape, had devolved into rubble banks of algae hosting the occasional lonely fish. Where the beaches of my youth, but for the occasional piece of driftwood, had been pristine strands of sand; they were now festooned with plastic detritus.

At the UN I coined the mantra I use to this day, “No healthy planet without a healthy ocean, and the ocean’s health is currently measurably in decline.” Wherever possible I utilized the breadth of the UN system to identify the various indices of the ocean’s decline: pollution, acidification, deoxygenation, warming, loss of coral, harmful fishing practices, over-fishing and so on.

Then, with like-minded ambassadors and the support of concerned elements of civil society, we fought the fight for the ocean to be included within the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Success was by no means guaranteed, but finally in 2015 as an integral part of the UN’s 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda, SDG14 was adopted with its call for the conservation and sustainable use of the ocean’s resources.

The next step was to ensure that SDG14 was being faithfully implemented, and here we had a problem, because while most of the other SDGs had a designated home within the UN system, WHO for health, UN Habitat for housing, UNFCCC for climate change, and so on, SDG14 did not have a home. While it’s true that we had FAO to attend to fisheries, UNEP to engage with coastal ecosystems, IMO for shipping, IOC for ocean science, ISA for the seafloor, and more; but there was no one agency with coordinating oversight for the ocean. It was thus that the UN Ocean Conferences came into being, with the responsibility of supporting the implementation of SDG14, or as I like to put it, of keeping SDG14 honest.

Since my appointment in 2017 as the UN Secretary-General’s Special Envoy for the Ocean, it has been my responsibility to lead global efforts to implement SDG14. With the health of the ocean continuing its decline, this has been a heavy responsibility, involving many jet-lagged moments of dejection in the depths of the night. But as a grandfather of four bright young girls facing the precarious future presented to their generation by climate change, in truth the responsibility bestows a bright light of opportunity, resolve, and hope. For by every beneficial fraction of a degree that our actions bring today to the amelioration of global warming and the safeguarding of biodiversity, we will lessen the levels of suffering of those who will experience the future.

Even though my path is one that pursues those opportunities with both hope and resolve, it would be disingenuous of me not to recognize the enormity of the challenges humanity has created for itself by our continuing production of greenhouse gases and the consequent warming of the planet. Every year that passes, now witnesses the ocean breaking its temperature records, with pursuant consequences of rising sea levels, marine biodiversity loss, and death of coral. As a result, the scope of ocean issues requiring urgent attention is daunting and we should not underestimate the testing tasks ahead.

To cope with the changes that will be coming upon us, we will be turning increasingly to the ocean for the solutions to our problems, be that in energy, carbon sequestration, medicine, food security, or nutrition. The term Sustainable Blue Economy has come into being, and in recent years has become accepted by international organizations like the OECD and the World Economic Forum as a prudent path to a resilient future.

Here I would emphasize the word “sustainable,” for use of the term without it could imply just one more round of linear exploitation of finite planetary resources. I often point out that the Sustainable Blue Economy is summarized in SDG14’s balanced call to conserve and sustainably use the ocean’s resources, implying circular practices existing in harmony with nature; for example, only fishing within biologically sustainable levels.

As an aside, when addressing the International Conference of Small Island Developing States (SIDS) in Antigua in May 2024, I said that by definition SIDS are oceanic countries, and in most cases, the size of their maritime exclusive economic zones far outstrips their land areas. Even with changes forced by rising sea levels, this remains an immutable fact. Thus, in the face of the great challenges of the future, islanders can rely on the ocean and the Sustainable Blue Economy in a way they cannot on the spoils of continental economies such as the tourism industry.

Sustainable Blue Economies entail decarbonizing ocean-based industries, promoting sustainable use and management of ocean resources, and pursuing nature-positive ocean-based sectors. In the latter sectors we find the various means of utilizing marine renewable energy, with the ocean’s tides, currents, waves, and winds able to provide us with all the renewable energy we need, many times over. When we combine that with the power of solar energy, we see that adequate investment in marine renewable energy, in nature-positive ways, will soon enable us to consign the planet-warming pollution of fossil fuel energy to a bygone era.

When it comes to sustainable use of ocean resources, we can be confident of future resilience emerging from scientifically managed wild-catch fisheries operating within strictly enforced biologically sustainable limits, and the development of truly sustainable aquaculture, with appropriate species being farmed and fed with appropriate feedstocks in locations that are in harmony with healthy marine ecosystems. Aquaculture’s output now exceeds that of wild-catch fisheries and this trend represents the future of aquatic foods, with FAO’s Blue Transformation strategy providing the basis for an efficient, inclusive, resilient aquatic food regime on the planet.

I have great faith in the role that algae have in our future. Measured in net weight, algae already make up 30 percent of global aquaculture, and research and product development is underway for its greater use in pharmaceuticals, nutraceuticals, textiles, clothing, cosmetics, bio-packaging, biofuels and biofertilizers, human food, and animal feed, particularly for sustainable aquaculture. Considering its carbon sequestration properties and the vast farming prairies the ocean offers for algae production; it is amazing that plastic got the free ride it did when algae was always available to us as a packaging material. If over the span of my lifetime, algae had received anything like the massive funding for research and product development that plastic has enjoyed from the highly subsidized petrochemical industry, I believe we would be living in a very different world.

In the field of decarbonizing ocean industries, we find the greening of shipping and ports, including transitioning propulsion of local coastal and river craft away from fossil fuels. Electrical power is coming forward as the clean energy alternative for short-haul marine craft like ferries and river transport, while green hydrogen, biofuels, methanol, and wind emerge as future alternatives for shipping propulsion. To foster these transitions, the International Maritime Organization has adopted a strategy to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from international shipping by at least 20 percent by 2030, while striving to achieve 30 percent. IMO also has an “enhanced common ambition” to reach Net-Zero GHGs by 2050.

Novel industries are emerging from greater research into the genetic properties of the ocean, so much so that marine biotechnology is emerging as another essential element of human resilience. In the fast-approaching post-antibiotic age, science points to the ocean’s properties, the majority of which are still unknown to us, as our pharmaceutical and nutraceutical frontier. On a recent visit to Iceland, I was introduced to an array of creams, cosmetics, supplements, nutraceuticals and pharmaceuticals, all based on cod enzymes and Omega-3 oils. Most inspiring was that this diverse product range was a beneficial outcome of the Icelandic cod industry’s policy of zero wastage.

If we accept that the Sustainable Blue Economy is a core element of human resilience on a dangerously warming planet, we need to be directing far greater financial resources towards it. The Sustainable Blue Economy currently receives a ridiculously low level of private and public sector investment—ridiculous, because if you need to build a lifeboat, and we do, you’d better start assembling the timber for the keel and planking before the flood starts.

If that sounds like hyperbole to you, I will justify those words. Firstly, let us recognize that in spite of all the good work under the UNFCCC and the Paris Climate Agreement, we are still on a very dangerous trajectory. The imperative of not exceeding 1.5 °C global warming becomes increasingly tenuous with each ongoing belch from a coal-fueled power plant. And with each passing year without wholesale radical transformation of human consumption and production patterns, in this critical decade, we are propelling our children and grandchildren towards a world of savage storms, devastating floods, famines, plagues, and wildfires—in short, a living hell for great swathes of humanity. Standing on this ominous threshold, investment in the Sustainable Blue Economy is the right thing to do for the security of the generations to come.

When I write that the Sustainable Blue Economy receives “ridiculously low levels” of investment, whether its OECD calculations, or those of the World Bank, performance figures to date bear out my remark. SDG14 is widely recognized as the most under-funded of all the SDGs. A World Economic Forum white paper released in June 2022 entitled “SDG14 Financing Landscape Scan: Tracking Funds to Realize Sustainable Outcomes for the Ocean” showed that $175 billion per year is needed to achieve SDG14 by 2030; and yet, between 2015 and 2019, below $10 billion was actually invested. OECD estimates that of the investment there is for SDG14, the main share comes from philanthropy and Official Development Assistance (ODA), with SDG14-related funding amounting to only 1 percent of global ODA. We must change that under-funding paradigm as if our futures depend on it, because as I have just explained, they do.

In response to this call for the climate finance needle to move decisively in the direction of the Sustainable Blue Economy, positive change is observable. The Green Climate Fund, the Global Environment Facility, the Asian Development Bank, the World Bank, wherever you turn, movement is afoot. But is it fast enough and is the private sector moving with the alacrity it should?

For very good reasons, the High-Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy, comprised of 18 serving heads of state and government, has been pushing for greater investment into the marine sector. The panel’s report “The Ocean as a Solution to Climate Change”, found that full implementation of ocean-based climate solutions that are now ready for action, could reduce the emissions gap by as much as 35 percent. The report identifies sectors for investment action to be marine conservation and restoration, ocean-based renewable energy, transport, tourism, and food. The panel concluded that reducing oil and gas consumption is critical to success in meeting global climate commitments and that stopping the expansion of offshore oil and gas extraction should go hand-in-hand with a demand-led phase-down of current production.

Judging by the billboards we see along the highways of the world, you could be forgiven for thinking the oil and gas industry is leading private sector investment into the bright future of green energy. But in a report issued in November 2023 by the International Energy Agency (IEA), we read that “a moment of truth is coming for the oil and gas industry,” with structural changes in the energy sector now moving fast enough to deliver a peak in oil and gas demand by the end of this decade under today’s policy settings. Contrary to those billboards, the IEA report states that oil and gas producers account for only 1 percent of total clean energy investment globally and that “for the moment the oil and gas industry as a whole is a marginal force in the world’s transition to a clean energy system.” Considering all that we now irrefutably know about anthropogenic GHG emissions from the burning of fossil fuels, the perils of global warming, and the climate crisis, the IEA statement is a damning indictment.

We now refer to the “triple planetary crisis” of climate change, pollution, and biodiversity loss. In my speeches at international gatherings throughout 2024, I have been talking about the monstrous moral malaise of doing nothing about it. While the oil and gas industry is up there in the lead of that malaise, and indeed foments and profits from it, in truth we are all caught up in the sticky grip of inaction. We are not transitioning fast enough in ensuring sustainable consumption and production patterns, as we all promised to do when the world’s political leaders adopted the Sustainable Development Agenda back in 2015. Thus, it is that I say to people young and old, look into the mirror and see yourself as a consumer who influences demand, as a citizen who influences policy. Whether a country, a transnational corporation, a local community, or an individual, we all have to ask ourselves what more we can do to reduce our carbon footprints? We all have choices to make.

It’s important to remind ourselves that positive action is not a pipedream. And so, in the face of the triple planetary crisis, what positive action has the international community been taking to ensure life is bearable on this planet by the end of the century? Well, the helpful news is that in spite of historic levels of geopolitical tension dominating world affairs, in recent times a powerful wave of ocean-related multilateral environmental agreements has swept around the world.

In Montreal in 2022, under the Convention on Biological Diversity, the Global Biodiversity Framework, with its target of protecting 30 percent of the planet by 2030, was adopted by all countries. At the United Nations in 2023, the High Seas Treaty (BBNJ) was agreed to, with ratifications of it now rolling in steadily. At the UNFCCC in Bonn, thanks to the annual Ocean-Climate Dialogues, ocean issues are now an integral element of international Climate Change negotiations. And recognizing that our scientific knowledge of the ocean is insufficient for us to make many planet-affecting decisions, Member States of the United Nations created the UN Decade of Ocean Science, 2021-2030. Thanks to the Decade’s creation, as evidenced by the tremendous success of the Ocean Decade Conference in Barcelona in April 2024, ocean science is now receiving more attention than ever before in human history.

At the time of this writing, negotiations to conclude a Plastics Treaty are underway to prevent plastic pollution, including of the ocean; while at the WTO in Geneva, negotiators are tantalizingly close to reaching an agreement that will eliminate the harmful fisheries subsidies that currently support overcapacity of the global fishing fleet.

All these strands of positive ocean action come together at the UN Ocean Conferences held periodically to assist the implementation of SDG14. I often refer to the ocean conferences as moments of truth in our relationship with the ocean, representing a week of intensive, inclusive consideration of ocean issues, during which we hold our feet to the fire of evidence. Co-hosted by Costa Rica and France, the third UN Ocean Conference will be held in 2025 in Nice, running from June 9th to 13th, preceded by special events on ocean science, coastal communities, and ocean finance.

I emphasize that all of these global gatherings are grounded in ocean science, hence the great importance of the Ocean Decade’s work. I also emphasize that 2022’s consensual adoption of the Global Biodiversity Framework, recognized that nature and nature’s contributions to people are vital for human existence, that living in harmony with nature is essential to our survival on this planet. As just mentioned, to ensure that eventuality, we included in the framework a target to protect 30 percent of the planet by 2030, agreeing to achieve this target by effectively conserving and managing, through ecologically representative and equitably governed systems of protected areas, and other effective area-based conservation measures.

It goes without saying that marine and coastal areas are a crucial element of that 30 percent, and that therefore the “30 by 30” target should be high on the agenda of all ocean-related organizations. In considering what qualifies as “effective area-based conservation measures,” it is clear that meaningful interaction with existing ocean organizations like Regional Fisheries Management Organizations and UNEP’s Regional Seas Programme is required, and I am at pains to stress this point at all relevant meetings that I am attending in 2024.

I was privileged to speak at the launch of the 2024 edition of SOFIA, the State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture report, when FAO presented it at the High-Level Event on Ocean Action in San Jose, Costa Rica in June 2024. In San José, FAO demonstrated again how well-governed, science-based management continues to be the most effective approach to conserving aquatic resources. But the SOFIA launch also recognized that over a third of global fish stocks are still not fished within sustainable biological limits. It was thus agreed that urgent action is needed to accelerate stock conservation and rebuild over-exploited stock, and that we must better use our knowledge and science to implement evidence-based management in those fisheries where overexploitation persists.

Looking ahead to the UN Ocean Conference in Nice, we are called upon to demonstrate that we are keeping faith with SDG14’s implementation. In that regard, we must face the fact that over-fishing is just not right. Thus, from February 24th to 27th, 2025, with a view to improving on delivery of SDG14’s demands, the Government of the Solomon Islands is convening the Honiara Summit, in cooperation with FAO, the Forum Fisheries Agency, my office, and others. The summit is being structured to enable alignment of fisheries strategies and action across all relevant stakeholders, with the ambition of having all RFMOs present with us in Honiara.

And yes, we must be prepared to grasp the thorny issues still confronting us, including the negative impact of various foreign fisheries access arrangements on coastal communities and the biodiversity within their waters; including greater respect for the rights and needs of small-scale fishers; ensuring aquatic foods are ethically and responsibly sourced; and better combatting illegal fishing through enhanced monitoring, control, and surveillance measures.

I would also underline here how extremely important it is that we don’t underestimate the harmful effects chemical pollution is having on animal and human health, and on the wider natural environment. That statement includes chemicals used in making plastics, most of which have never been tested for safety. Reliable research studies are already telling us that many of the thousands of chemicals used in plastic are hazardous and may be causing cancers, mutagenicity and endocrine disruption. Thus, with the Plastics Treaty heading towards its concluding phase, I hope there is still opportunity for the human health provisions within it to be robust and meaningful.

Over the next five years, it is clear that our focus should be on accelerating progress on implementation of all the SDGs, with a redoubling of our efforts to end poverty and hunger, advance gender equality, and stop our war against nature. And for those of us working to achieve the targets of SDG14, the goal of conserving and only sustainably using the ocean’s resources, the call is to try harder. For as long as the ocean continues to be polluted with our chemicals and microplastics, as long as we overfish and progressively destroy the ocean’s biodiversity, and as long as the ocean is warming, acidifying, and losing its oxygen, we are required to exert every effort to stop the decline in the ocean’s wellbeing.

But let us acknowledge that we are starting to change. Having become aware of the error of our ways and having seen the evidence of our wrong-doing along our shorelines and seafloors, we are moving to nature-positive ways of thinking, towards circular economies, transitioning away from the polluting single-use culture that rampant consumerism has bred into our cultures. But are we transitioning fast enough? The answer to that is, not yet.

These are the days for innovation and solutions. These are the days when humanity’s genius for invention must come to the fore, and time-tested ways of sharing in times of need are exercised to the best of our ability. The central message is crystal clear: stop burning fossil fuels and transition rapidly to renewable energy. And for the good of those to come after us, we are all required to stay true to the tenets of the Paris Climate Agreement.

I conclude this essay with a tilt towards young people. I was present with the UN Secretary-General, Antonio Guterres, at the 2022 UN Ocean Conference in Lisbon, when he deeply apologized to the youth of the world for the dystopian future our generation has been preparing for them. He promised that we would spend our remaining years working in partnership with young people to strive towards the 1.5°C climate goal. He has since conveyed throughout the UN system that henceforth youth must not be at the periphery of our meetings, but rather at the meeting tables, helping to negotiate the future they will inherit. There is a compelling logic in having suitably qualified young people at the table, for they will live with the long-term effects of the decisions taken.

To overcome the challenges ahead, young people must be fully conversant with the principles of “Ocean Literacy” and should be part of the movement to spread the word that an essential component of our security on this planet is the restoration of humanity’s relationship with the ocean to one of respect and balance. Considering the ocean’s role in keeping us all alive, you would think that respect would be a given; but levels of pollution of the ocean and the over-exploitation of its resources show this is not yet the case. Halfway through the course of the Ocean Decade, it is our responsibility to advocate for Ocean Literacy to be taught in every corner of our world.

It is said that action without knowledge is foolishness and that knowledge without action is wastefulness. We have the knowledge, so let’s be wise with what we do with it, and let us get on with the action required to achieve SDG14, our agreed goal of conserving and only sustainably using the ocean’s resources. We should not be distracted by vapid choices between optimism and pessimism in these matters; ocean activists must instead be hard-nosed pragmatists, for we have so much work to do.

In the name of intergenerational justice, hopefully imbued with love, the realities of our planetary responsibilities oblige us to start living in better balance with the world around us, to stop making war on nature, to make peace with it, and thereby to stop the decline in the ocean’s health. We must make that nature-positive pivot as if our grandchildren’s lives depend on it, because for many of them, that will be the case.

So let us be strong in our conviction that positive ocean activities will have their desired effects. Let us strengthen our grip on the conviction that reason and innovation will allow us to overcome the mounting challenges ahead. Let us take the tide while it serves, and through faithful implementation of SDG14, may we thereby bequeath a healthy ocean to our children and grandchildren.