Zoran Čičak is a member of the Ohrid Group, a Macedonia-focused body comprising eleven international policymakers, diplomats, and scholars. You may follow him on Twitter @zorancicak.

Zoran Čičak is a member of the Ohrid Group, a Macedonia-focused body comprising eleven international policymakers, diplomats, and scholars. You may follow him on Twitter @zorancicak.

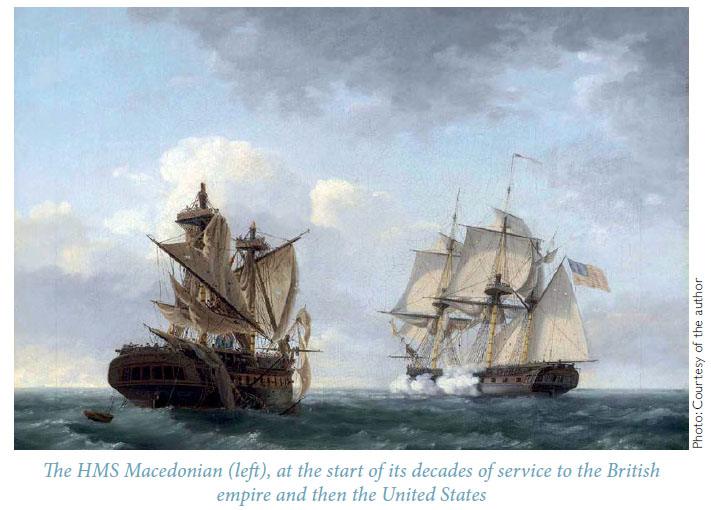

In the early nineteenth century, the British Royal Navy had a frigate named the HMS Macedonian. In the 1812 war, this man-of-war was captured near Madeira in the Atlantic by a more powerful warship, the USS United States, but its name was not subsequently changed: it simply became the USS Macedonian and remained in the American fleet for another 20 years. So one could say that nearly two centuries ago, the name Macedonia was cherished and shared by both London and Washington.

The United Kingdom and the United States, once adversaries, are now close allies in NATO. The old naval battle nonetheless remains in our memories, immortalized by American artist Thomas Birch—his masterpiece was bought by then-First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy in 1961 and became part of the White House gallery until sold at auction in 2008.

Let us see where the Macedonian state and national ship are today, having sailed through uncharted and stormy Balkan waters for a quarter century.

In mid-June 2018, the two governments of led by prime ministers Zoran Zaev (Skoplje) and Alexis Tsipras (Athens), respectively, reached a historical compromise over the name dispute, thus ending an old and, as many argue, irrational conflict between Macedonia and Greece. The interim solution of calling the country the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FYROM) was replaced by a more precise geographic qualifier: the Republic of North Macedonia (RNM).

In late June and early July 2018, the EU and NATO recognized this tremendous political success and extended an invitation to Macedonia to start the process of negotiations to join both regional organizations.

On September 30th, 2018, more than 91 percent of Macedonian citizens participating in a referendum approved the proposal to adopt the constitutional changes necessary to implement the Prespa Agreement. However, only 37 percent of eligible voters took part in this referendum, raising the issue of its legitimacy.

About a fortnight later, on October 19th, 2018, a two-thirds super-majority of Macedonian parliamentarians voted to launch the process of constitutional change.

Finally, on January 11th, 2019 deputies in the Macedonian parliament completed the procedure of constitutional changes, thus approving the new name of the country and opening the way for their Greek colleagues to ratify the Prespa Agreement two weeks later.

Four Key Pillars

There are four key points that ought to be highlighted in the amended constitutional text. First, Macedonia and Greece did not negotiate

as yesterday’s foes, but instead as tomorrow’s friends. Such an approach was the only one that could have made a breakthrough possible, which it eventually did. While this was initially just an assumption, it is now a matter of fact.

There is no better confirmation of this than the fact that both Macedonian and Greek opponents of the Prespa Agreement share the approach in opposing the deal. They both continue to think in terms of the past, rather than the future—for the only world that exists in their minds is the world of eternal foes.

Second, the breakthrough of the Prespa Agreement was only to be made by truly democratic governments—ones with profound respect for the rule of law, human rights, freedom of the media, and other core European values.

Therefore, a political breakthrough was not really possible before the onset of substantial democratization in Macedonia proper, which took place in mid-2017.

Third, Macedonia is not a remote island, somewhere far away in the ocean—it is located in the middle of the Balkans, a region that has been contaminated by nationalist, war-mongering, xenophobic, and essentially anti-European policies for the last 25 years. Macedonia was actually the first country in the region to opt to leave such an environment for good.

The Macedonian success will certainly have a deep impact on its neighbors by showing them that, while the road to Europe might sometimes be cumbersome, it eventually pays off much more than the recycling of old nationalist narratives. Macedonia thus has the potential to become a game-changer in a deeper, historical sense, and to stand at the forefront of new policies.

Fourth, it seems that wider international reactions to the Prespa Agreement have only confirmed our initial assumption: just as true friends of the European idea extended their genuine support to the Tsipras-Zaev deal, so did its adversaries try to undermine Europe’s extension in the Balkans.

In other words, the battle in Macedonia is not a battle for Macedonia only; rather, it is a struggle for the spirit that will eventually prevail in Europe at large.

New Paradigm

As a matter of fact, the core issue behind the Macedonian-Greek dispute was irrational in its character for most of the past 25 years. It was a battle for Hellenistic Macedonian heritage. While historians in both countries, much like their colleagues in the rest of the world, know very well that neither contemporary Macedonians nor contemporary Greeks are genuine descendants of ancient Greeks (the name, indeed, used to designate a whole, now extinguished, civilization, rather than a particular nation comparable with modern nations), such an assumption remains a myth in both societies.

One should accept, of course, the fact that more than a few contemporary nations are identified, inter alia, by their respective myths: many Englishmen and women believe that King Arthur really existed, the Spaniards continue to dream about El Cid Campeador, the Swiss like stories about William Tell, and, similarly, the Italians enjoy hearing about Sicilian Vespers.

These myths most often do not correspond entirely, or at all, with historical truths, but this fact remains irrelevant: as Friedrich Nietzche once said, “it is precisely facts that do not exist, only interpretations.”

Modern Macedonia, however, is a nation with clear and distinguished Slavic origins: Macedonians are, linguistically, culturally, and historically, much closer to Serbs, Bulgarians, Croats, and Montenegrins than to Greeks—both ancient and contemporary ones. In addition, the modern Macedonian state was actually created during the anti-Fascist insurrection of World War II and built its statehood within the framework of the federal structure of communist Yugoslavia.

When signing the Prespa Agreement, Zaev made his choice clear: by breaking with historical myths and opting for the modern roots of Macedonian identity instead, he accepted to be sufficiently distant from his southern neighbor in order to stop arguing about the past.

Over in the Hellenic Republic, Tsipras realized the simple truth that only a stable and strong Macedonia on his northern border is in the best interest of a stable and strong Greece. As the aforementioned dispute never contained a territorial issue, it was easier for the two parties to accept the separation between “North” (Slavic) and “South” (Hellenic) Macedonia—a division that had already taken place on the ground—in fact, one that had happened a hundred years prior, when the Ottoman Empire was almost totally expelled from Europe in a larger military

effort conducted by the Serbian, Bulgarian, and Greek armies in 1912.

This is exactly the core of the new paradigm that the Prespa Agreement represents: by giving up putative claims, which are not only irrelevant but also imaginary, both Skopje and Athens have solidified their international positions around their essential interests. The most important of such interests, however, is a common one: to continue to live as neighbors, but henceforth within the EU and NATO—umbrellas with proven track records of being able to accommodate differences.

Conditio Sine Qua Non

Back in 1973, as a young boy, I was traveling abroad for the first time in my life, to Greece. We exited Yugoslavia (and Macedonia) via the border crossing at Bogorodica/Evzoni. Our bus stopped in the middle of the night, just so it could allow a sleepy Greek policeman to come aboard. He checked our passports carefully, looking for one small detail only: while all passengers at the time had the same red Yugoslav passports, there was one minor detail that represented a difference between us: the holders of passports issued in Macedonia had a letter “M” at the beginning of the serial number, which indicated the federal unit whose interior ministry was the passport’s issuer. The Greek policeman refused to put a stamp in those passports with the letter M, opting instead for a stamped piece of paper—a common procedure for all regimes in the world that wish to make a symbolic point by not recognizing some foreign entity.

At that time, Greece had been under the rule of the colonels for six years (the military junta was deposed in 1974), and creating tensions with the Macedonians served as an instrument of additional national homogenization for the Greeks themselves. Yugoslavia, however, was at that point still far too strong to accommodate any Greek complaint against one of its federal units, so the issue did not really exist until 1992.

Both Greece and Macedonia are now democratic countries; they share the vision of core European values: the rule of law, human rights, freedom of the media, and, last but not least, they share the same cosmopolitan, leftist and anti-fascist heritage.

Was it possible for the Macedonian-Greek dispute to be resolved without such a political and ideological landscape in both countries? Would the negotiations ever come to fruition if, instead of Zaev and Tsipras, the two countries’ governments were headed by two old-fashioned, stubborn, and evil-obsessed rightists like Marine Le Pen or Nigel Farage? Probably not—or, at least, that’s what recent history suggests.

Politics is of course about facts and interests, but it is above all about sentiment. In order to create an environment in which compromise is possible and sustainable, both sides needed to create enough positive sentiment for such a compromise within their respective communities.

In the spring and summer of 2017, we witnessed how the extreme right in both Macedonia and Greece desperately tried to undermine the process of rapprochement between the two countries; how they disseminated fake news on both sides; how they demonized both leaders as national traitors; how they occasionally resorted to violence in Thessaloniki and Skopje; how all of the aforementioned events were coordinated both between themselves and within a wider international anti-European alliance.

Indeed, Macedonian and Greek extremists demonstrated a high level of mutual understanding in this evil endeavor—just like so many others in the Balkans over the past quarter century.

The blueprint of “best enemies” has held, and still predominantly holds, the Balkans in limbo; had the Prespa Agreement failed, there was nothing that could have prevented Macedonia from remaining in this regional quagmire.

In that respect, democracy eventually emerged as the triumphant quality that has made a difference by providing the critical political will needed to accept the risks and subdue the evildoers on both sides.

That being said, of course, one point remains to be clarified: with the very term “democracy,” in this context, we are not only taking into account the fact that one political option currently holds the technical majority in the electorate; as history has taught us—based on the examples of so many authoritarian leaders (not to begin and end with Adolf Hitler)—the mere fact that a certain political option has a majority does not automatically make it a democratic one. A political option also needs to have its own values and vision.

In the cases of Macedonia and Greece, apart from the majority support they have enjoyed in their respective countries, Zaev and Tsipras also share more profound values and visions of the future—a future that will be common for both countries, and a future that will be European.

This shared vision of the Balkans and Europe alike required both leaders to exhibit simultaneously political and personal courage, as each had to face and subdue his own demons first. The eventual success, of course, was common to both men, and it was only possible as a shared endeavor. This explains, inter alia, why Zaev and Tsipras were recently jointly nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by so many European parliamentarians and other eminent international figures.

Balkan Game-Changer

The Macedonian-Greek dispute, unfortunately, is not the only one that currently exists in the Balkans. The dispute between Belgrade and Pristina over the status of Kosovo as well as the one concerning the internal political architecture of Bosnia and Herzegovina remain painful reminders of the region’s decade of ethnic and religious wars.

Some analysts, however, rushed to praise the Prespa Agreement as an ideal blueprint that might (and should) be followed in other parts of the Balkans. But does the agreement represent some kind of magic wand?

I believe that this question is much too complex to be answered simply: each Balkan dispute is specific and should be considered within its own geographic, historical, and demographic context. However, one point cannot be neglected: in the Balkans, there is no other pair of truly democratic governments involved in negotiations with each other as was the case with the Prespa Agreement.

A majority of other Balkan governments are run by leaders and political elites who share nasty legacies of the ethnic wars of the 1990s.

Some of them are the biological descendants of wartime leaders, like Bosnian Muslim leader Bakir Izetbegović; some are just their spiritual descendants, formatting themselves in an inherently anti-European political mindset, like Serbia’s President Aleksandar Vučić; other were involved in war crimes themselves, epitomized by Kosovo’s current president Hashim Thaçi and current prime minister Ramoush Haradinaj.

At the same time, a lot of these are involved in different corruption schemes, and more than a few of them, according to credible Western intelligence reports, remain dangerously close to transnational organized crime networks—both within and beyond the region.

This dark legacy has had a deep and enduring impact on public opinion, social structures, dominant symbols, and values in all Balkan countries. It remains one of the key factors that still shape social elites and keep them locked in what is basically an oriental and ahistorical mindset.

Regional disputes, essentially the same or similar to the Macedonian-Greek one, will be entirely unsolvable if they continue to be handled by authoritarian strongmen. This is true for one simple reason: these strongmen will not generate enough positive sentiment in their respective public opinion environments to make any solution possible. Vučić and Thaçi, for example, are incapable of resolving the Serbia/Kosovo issue, much like Milorad Dodik and Bakir Izetbegović were unable to resolve the problem of Bosnia’s internal architecture.

Whatever their public rhetorical professions to the contrary, all of them have, at bottom, a profound hatred not only of the Western political community, but also of Western values.

All of them intimately want to keep their respective societies locked in a nightmare for as long as possible. All of them know very well that inspiring ethnic hatred and fears of new wars still remain their best chances of survival against modernity, European values and, ultimately, their own peoples. All of them are also aware that the criminalized elites in the country they presently lead are utterly incapable of building up societies around core European values.

All of them—to cut a long story short—remain deeply enthroned in Oriental despotism, as defined by the likes of Gibbon, Montesquieu, Marx, and Wittfogel.

Macedonia might therefore be a game-changer in the Balkans, but not in the simplified sense that some Brussels bureaucrats seem to think. The Prespa Agreement itself is not a blueprint for anybody else. However, the way in which Macedonia has been reforming its society, putting aside nationalist dreams and ethnic hatred, and building a modern, multiethnic country, deserves to be followed more broadly.

In that respect, it is clear why the Balkan autocrats are afraid of the so-called “Macedonian scenario”: the very concept of what Florian Bieber and others writing in the pages of Horizons have called “stabilocracy” is dependent on a state of permanent instability, perpetual war, inclined-to-war narratives, and preventing ordinary people from meeting and learning about each other. Only in that manner—by holding their populations and the whole of Europe hostage—can the Balkan strongmen justify their political monopoly.

Truly to his lasting credit, Zoran Zaev tried a completely different approach: for the first time since the death of Yugoslavia’s Josip Broz Tito in 1980, a political leader in Macedonia attracted the support of both ethnic Macedonians and Albanians, bridging ancient and perhaps even feudal divisions.

Frankly, Zaev did not have too many choices: had the Macedonian route to modernity failed in the summer of 2018, a new opportunity would not have presented itself within this generation—the West would have most likely abandoned its unreliable partner and drawn up an iron curtain of sorts around the country all over again, once more excluding Macedonia from the process of further political, economic, and military integration. Most likely—again, to speak frankly—more than one European leader would have felt a sense of relief for not having to handle what is believed to be yet another cumbersome accession process.

Under such circumstances, it is likely that ethnic Albanians in Macedonia would have had second thoughts and believed that their route to the future ought to go via Tirana or Priština, rather than via Skoplje. Recent ideas about a Serbia-Kosovo territorial swap—promoted by two local strongmen, advocated by several European and American adventurers, and circulated by some international media and think-tanks over the last several months—could (and in fact temporarily did) only uphold such irredentist views.

Age of Pericles Anew?

If there cannot be a European Macedonia, would it be possible to preserve any Macedonia? For more than one reason, the reverse road now seems out of reach—there could be no status quo. Zaev was fully aware of such a risk. He gambled and won.

However, the outcome of this gamble has carried a strong message beyond Macedonia itself. If ethnic Macedonians and Albanians in Macedonia could be brought together to build up their joint future, why, then, wouldn’t Serbs and Albanians, or Serbs and Muslims, or Croats and Muslims, or even Croats and Serbs, be able to do the same? Should all of them decide to follow the Macedonian scenario, what then would be the remaining raison d’être for other authoritarian leaders in the Balkans?

One truly multiethnic country in the middle of the Balkans could easily start a process that would culminate with the creation of a multiethnic Balkans—a vision of the peninsula that carries a striking resemblance to Tito’s Yugoslavia, the Age of Pericles that vanished in the last decade of the twentieth century.

Damon Wilson, Executive Vice President of the Atlantic Council and a member of the Ohrid Group, put this in a very straightforward manner in a recent speech in Washington, DC:

The free world is facing a pretty serious challenge from an alternative model of growing authoritarianism, benefited by the fact that democracies are doing a lot of fighting within the family. A key to pushing back against this threat is resolving unfinished business and there is clearly unfinished business in Southeast Europe.

“The Macedonian scenario”—to once again use the term that has been a nightmare for so many Balkan leaders

—means just that: only together

can the free world face corrupt

authoritarian regimes.

The Impact on Wider Europe and Vice Versa

The wider impact of the Macedonian-Greek accord and its related events is sometimes viewed in a simplified manner: with the United States, NATO, and the EU all lined up as supporters of Macedonian integration in the military and political architectures of the West, and with Russia as its principal opponent.

While such a statement is not entirely factually incorrect, it certainly cannot fully explain the complexity of the situation that has occurred around both Macedonia and Greece—both of which were exposed to various attacks and pressure for the better part of 2018. Whoever was against European values on the Old Continent—be they German right-wing extremists, Viktor Orban’s revisionists, Le Pen’s and Salvini’s neo-fascists, or Austrian and Serbian populists—trained themselves on the Greek and Macedonian reformers by trying to crush them. Like in Günter Grass’s 1979 film The Tin Drum, whoever hated Europe hoped for the Macedonian-Greek deal to fail.

Indeed, one can imagine why Russia might be opposed to NATO expansion. It is, however, not that difficult to understand why European populists and the extreme right have the tendency to view today’s Macedonia in the way their ideological great-grandfathers viewed Spain prior to Francisco Franco: as a battleground.

It might, of course, be a matter of pure solidarity: one prominent European populist, former Macedonian Prime Minister Nikola Gruevski, had to fall from grace in order for the Prespa Agreement to be reached. He was put on trial in several nasty-looking cases, the first of which has already ended and confined him to a jail cell, when a complex mechanism was put in motion by several secret services acting together. Albeit without being in possession of a passport, Gruevski was smuggled out of Macedonia during one weekend in November 2018 and was driven to Budapest via Albania, Montenegro, and Serbia. Upon arrival he was granted asylum in Hungary by the government led by his old populist friend, Victor Orbán.

Indeed, the nightmare of having to await a similar fate might also represent the fear of all other European populists, as we have already seen. An alternative is a viable option and could indeed reoccur in their countries.

However, the key reason for the anti-Macedonian bias among European populists is a more practical one: ahead of 2019’s key elections for the European Parliament, they seem desperate to demonstrate not only that the EU’s institutions are dead—admittedly, these do not operate at their best—but that the very idea of European values is dead. The example of Macedonia and Greece, effectively demonstrating the opposite, is exactly what populists would prefer not to see.

Quite understandably, some small war in the Balkans would serve their purpose even better. The symbolic failure of efforts by both Tsipras (who has demonstrated utmost patience and diplomatic skills in handling the complex European financial agenda) and Zaev (who had to literally fight his way through to assume the position to which he was elected) would serve such a purpose even better.

It is therefore quite clear why the key meetings between Russian secret service operatives and envoys of the former Macedonian regime had to take place in Orban’s Budapest; why the most savage attacks against Macedonia happened in the obscure tabloid newspapers of Vučić’s Belgrade; and why Russian diplomats had to be expelled from Athens.

Finally, how this logic of mutual solidarity operates between Balkan strongmen might be explained, probably in the clearest way, by the behavior of Gruevski,s successor as VMRO-DPMNE leader, Hristijan Mickoski. Before the former dared to leave Macedonia, the latter had to pay (at the time) clandestine visits to both Orbán in Budapest and Vučić in Belgrade. At the time of this writing in November 2018, nothing leaked from any of the meetings: for the Balkans Cosa Nostra, the omerta has always been the law of the land.

The struggle in Macedonia, therefore, is not only a struggle for Macedonia—it is also a struggle for the spirit that will prevail in Europe in 2019 and beyond.

Faced with aggressions emanating from the Trump Administration, geopolitical challenges coming from Russia, security challenges arising from Turkey, and

economic challenges originating from China, Europe can survive only if it speaks in a unified voice. That explains why all its global competitors—America, Russia, and China—are all too happy to see Europe fragment itself even further, and why they cherish any sign that the EU has abandoned the inherent values of the union: its antifascist heritage, the rule of law, human rights, secularism, and freedom of the press.

The May 2019 election for the European Parliament remains crucial to shaping the new European identity. Whether it will be about Ukraine, Kosovo, Brexit, Cyprus, Syria, Iran, or Transatlantic trade, the fate of our continent will ultimately depend on people capable of understanding what is at stake and those ready to fight for it.

The drive for the hearts and minds of Europeans is operating at full steam—France, Sweden, Germany, the Netherlands, and Slovenia have all thus far managed to resist the four horsemen of the Apocalypse: Nationalism, Xenophobia, Populism, and Particularism. Great Britain and Poland are still fighting for their European souls. Italy, Hungary, and Austria, for the time being, appear all but lost—although this might all change soon. The struggle for values, one in which Europe has most certainly entered, is replacing old national allegiances with new transnational ideological alliances, both on the right and left alike.

So far, this struggle has been mostly virtual: the two sides have been engaged with each other through the media and via social networks, remaining busy with the production of spin and fake news. However, it seems as if Anton Chekhov’s old advice has migrated fromthe theatre to real life: “If in the first act you have hung a pistol on the wall, then in the following one it should be fired.” Two prominent European democratic politicians have been murdered: Serbia’s Oliver Ivanović in Kosovska Mitrovica and Poland’s Paweł Adamowicz. Within the span of one year, both became victims of an atmosphere of hatred and extremism, incited, inter alia, by their own respective governments.

One important puzzle in this new European mosaic that is still in the process of establishing itself is certainly Macedonia—both as an important transit country and as a potential blueprint for further change in the Balkans. In that respect, membership in both the EU and NATO remain firm anchors for the Macedonian ship of state. Membership in both blocs would serve as a double guarantee of Macedonia’s external borders and internal ethnic peace and civic stability, a way out of the centuries-old world of Balkan provincialism, as well as the road by which to enter the wider European world of partnership.

Indeed, this world is itself far from perfect—the EU is undergoing deep changes—but, for Macedonia, and for the rest of the Old Continent, European and Euro-Atlantic integration still represent the best of all possible worlds, as the title character in Voltaire’s Candide was known to exclaim.

There are, of course, shortcomings in such a world. It needs improvement, which would ideally render it more functional and connected with the concerns of ordinary people.

It has to embrace the anti-fascist heritage that the EU was originally built on and distance itself from historical revisionism. Its architecture needs to be made simpler and more efficient.

All these battles, of course, are far from being simple and easy, but it is also worth fighting for each of them. This struggle is possible only from within—it has never been possible to improve any community from the outside.

This is exactly the lesson that Macedonia, by gallantly fighting its own old stereotypes, prejudices, and superstitions, learned on its own—but in so doing it has also provided the rest of Europe with a lesson to learn.