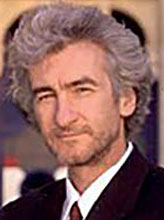

Peter Nolan CBE holds the Chong Hua Chair (Emeritus) in Chinese Development and is the Founding Director of the Centre of Development Studies at the University of Cambridge. He is the Director of the Chinese Executive Leadership Programme (CELP) and Director of the China Centre at Jesus College, University of Cambridge. An earlier version of this essay was presented in Paris at the 2018 Silk Road Forum as part of a keynote panel discussion entitled “BRI and the New Round of Technological Revolution.”

Peter Nolan CBE holds the Chong Hua Chair (Emeritus) in Chinese Development and is the Founding Director of the Centre of Development Studies at the University of Cambridge. He is the Director of the Chinese Executive Leadership Programme (CELP) and Director of the China Centre at Jesus College, University of Cambridge. An earlier version of this essay was presented in Paris at the 2018 Silk Road Forum as part of a keynote panel discussion entitled “BRI and the New Round of Technological Revolution.”

From the Han Dynasty (202BC-220AD) onward, China was ruled by a meritocratic bureaucracy. The core principle of the bureaucracy was pragmatic, non-ideological problem-solving in order to ensure popular welfare. This system combined the dynamic force of the ‘invisible hand’ of market competition with the ‘visible hand’ of ethically-guided government regulation.

As a general rule of the course of a two-millennial history, the Chinese bureaucracy undertook key functions that were necessary for a prosperous economy:

- ensuring peace, unity, and integrated markets;

- water control (both central and local);

- famine prevention and alleviation;

- commodity price stabilization;

- legal protection for trade and property;

- support for knowledge transmission (e.g. encyclopedias).

Moreover, China had vast internal trade and flourishing long-distance trade across the South China Sea. It achieved sustained innovation and technical progress, including shipbuilding, navigation, metallurgy, porcelain, paper and printing, weaponry, textiles, mining, deep drilling, and the ubiquitous industrial application of water power.

These innovations were mainly the result of competition between profit-seeking firms.

By the European Middle Ages, there was a wide technological gap between China and the West. Europe’s technological progress during the Enlightenment was heavily dependent upon technological transfer from China along the trade routes of the Silk Road. The famous British sinologist Joseph Needham observed:

The reciprocating steam engine, which attained its definitive form around 1800 AD, consisted essentially of two structural patterns [the double-acting piston-bellows and the conversion of rotary to rectilinear motion], which had been working widely and effectively in China since about 1200 AD. That these patterns passed into it by a long chain of genetic connections is overwhelmingly probable.

Needham concluded that no single man was the “father of the steam engine, no single civilisation either.” In any event, by the early eighteenth century, the West had closed the technological gap with China and there was little difference in Chinese and European technologies.