- Home

- Horizons

- The Axis of Necessity | How the War in Ukraine Adds a Strategic Depth to China-Russia Alignment

Alexander Gabuev is Director of the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center in Berlin. You may follow him on X @AlexGabuev.

Alexander Gabuev is Director of the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center in Berlin. You may follow him on X @AlexGabuev.

During his final big rally before the 2024 U.S. presidential election, Donald Trump outlined a key foreign policy objective: preventing a Russia-China alliance. “I’m going to have to un-unite them, and I think I can do that,” Trump stated in an onstage interview with political commentator Tucker Carlson. This strategy, widely referred to in Washington as “reverse Kissinger” and supported by his national security team, was seen as a foundational step toward his goal of ending the war in Ukraine and establishing a new détente with Russian President Vladimir Putin.

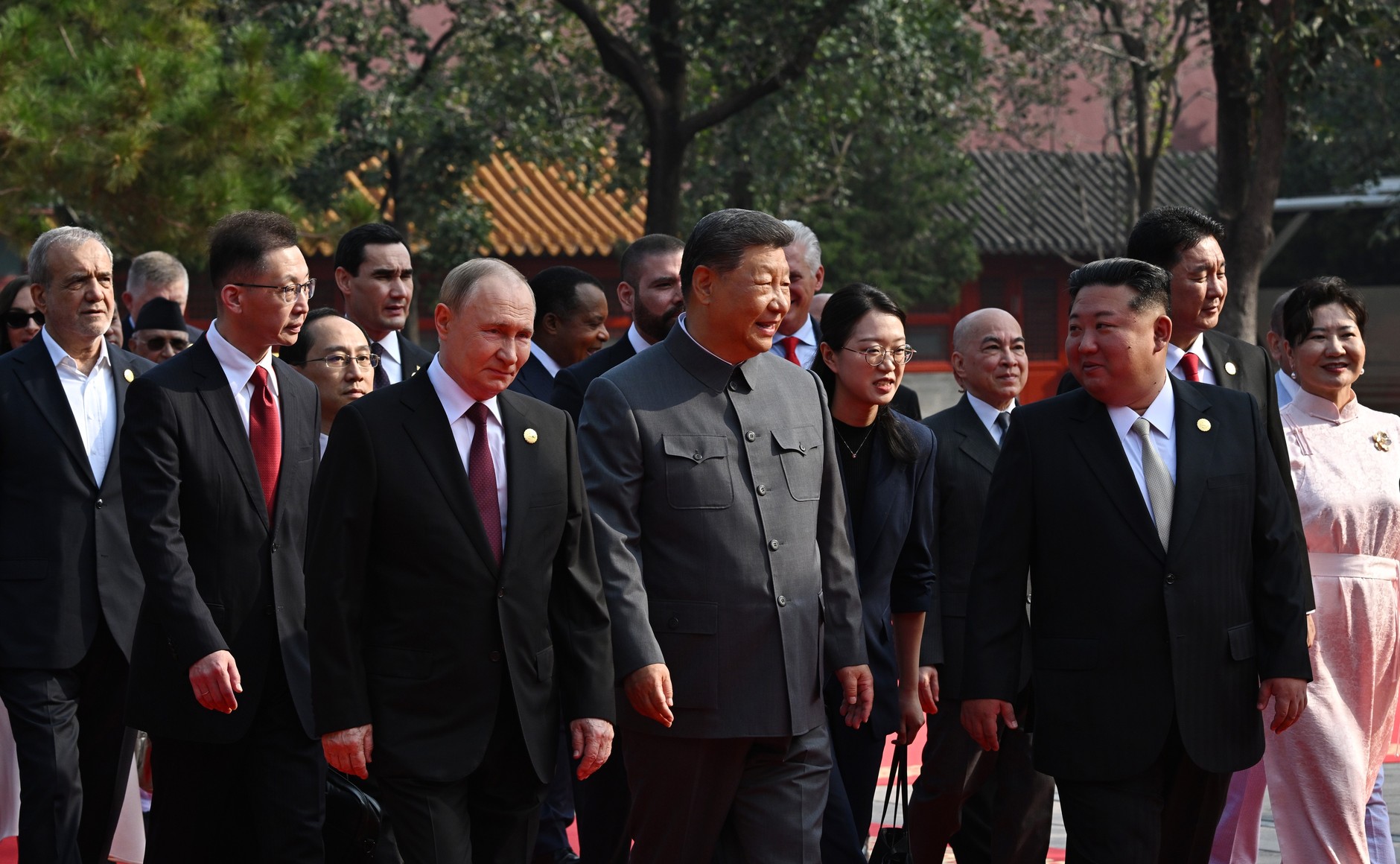

Presidents Putin and Xi arrive at the military parade in Beijing to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II | Source: Kremlin.ru

However, as the first anniversary of the Trump presidency approaches, the United States is measurably further away from this goal. The administration’s recent strategy of using coercions and sanctions to enforce peace negotiations has backfired—driving the Kremlin deeper into China’s economic and strategic embrace.

Simultaneously, Beijing has demonstrated profound resilience to American pressure. The Chinese leadership effectively weaponized its dominance over critical minerals and magnets, fighting the trade war to a standstill achieved on its own terms—an outcome that was hard to imagine just a few years ago. Consequently, Beijing is more confident than ever before, seeing no need to abandon Russia. Instead, it can comfortably stand by its partner while enjoying an increasingly dominant command of the bilateral relationship.

The deepening strategic alignment between Russia and China is a defining geopolitical trend. While Vladimir Putin’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine has cemented this nexus, its foundations are deeper, rooted in the fundamental national interests of both powers. The partnership is driven by the conscious efforts of Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin, as well as being an unintended byproduct of the deepening schism between both nations and the West. As a result, Western hopes of driving a wedge between Moscow and Beijing are likely futile, as the alliance serves both their interests.

However, the Russia-China relationship is not static. It is defined by a growing asymmetry in China’s favor, and its future trajectory is not set in stone. The trend remains contingent on multiple factors—including the eventual outcome of a power transition in Russia after Putin.

A Limited Partnership

The foundations of the modern China-Russia partnership were laid long before the 2014 annexation of Crimea or the 2022 war in Ukraine. Following the bitter Sino-Soviet split of the 1960s-1980s, three internal drivers pushed the two pragmatically toward reconciliation.

First, they prioritized resolving their longstanding territorial conflict, culminating in the full delimitation of their 4,200-kilometer border by 2006. Second, they shared a natural economic complementarity: Russia possessed vast natural resources but needed capital and technology, while China had the inverse. Finally, as Russia grew increasingly authoritarian under Putin after 2000, their political interests aligned. Beijing and Moscow increasingly acted as a duet in the UN Security Council, jointly pushing back against Western-led initiatives—such as sanctions on authoritarian regimes.

Layered on top of these three internal drivers was the “secret sauce” of anti-Americanism. Both Beijing and Moscow shared a perception of the United States as an ideology-driven global hegemon. They believed that the U.S. was actively seeking regime change in their capitals and obstructing their “rightful place” in the world order. This anti-American sentiment became a crucial policy driver after Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the subsequent war in Donbas. In response to Western sanctions, the Kremlin initiated a “pivot to the East,” a strategic move designed to offset Western economic pressure and bolster and Russia’s resilience by deepening its ties with China.

As a result, China’s share of Russia’s trade balance steadily increased, rising from 10 percent before the 2014 Crimea annexation to 18 percent by the eve of the 2022 invasion. The relationship was highly asymmetric. For Beijing, Russia was a minor economic player, accounting for only 2.5 percent of China’s total trade. While the partnership’s importance is not measured by trade alone, this reality underscored that the dynamism of the Chinese economy was far more dependent on its ties to the West than on its partnership with Moscow.

Similarly, the EU remained Russia’s indispensable economic partner, accounting for 38 percent of its trade and serving as its primary investor and technology provider.

The Great Numerical Leap Forward

This economic context explains China’s preference to maintain ties with Russia since the latter’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Beijing has skillfully pursued a two-track policy. On one track, it provides critical support. It refuses to condemn the aggression, and seizes economic opportunities, such as buying discounted Russian oil. On the other, it mitigates its own risk. It has refrained from sending large quantities of direct lethal aid, formally upholds Ukrainian territorial integrity in its public statements, and crucially, has its largest banks avoid gross violations of Western sanctions to protect its own access to the global financial system.

Despite its initial caution, China has unambiguously become the primary lifeline for Putin’s rule and his war effort in the four years since the full-scale invasion. Western sanctions left Russia no other choice but to shift to Chinese-manufactured goods, causing bilateral trade to explode from $147 billion in 2021 to a peak of $245 billion in 2024. While 2025 volumes are poised to fall by roughly 10 percent, this is not a reversal. Rather, it reflects lower commodities prices and a Russian market now fully oversaturated with Chinese goods amid an economic cooldown.

Even with this dip, China’s structural dominance is clear: by the end of 2025, it will account for over 40 percent of Russia’s foreign imports and more than 30 percent of its export revenues.

The Sino-Russian partnership has also visibly expanded in the critical area of security and military cooperation. Far from distancing itself from its Russian counterparts, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has actually increased the number of joint activities, including annual military exercises. Although the scale of these drills remains limited for now, the PLA and the Russian Armed Forces are steadily developing a deeper level of interoperability—signaling a clear strengthening of their military ties.

One of the most substantial shifts in Beijing-Moscow ties since 2022 has been the rise of in-person engagement between their elites. Previously, close personal bonds were rare, existing almost exclusively between Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin. That situation is rapidly changing due to a deliberate effort by both leaders to force their teams to interact. Since 2022, most of Russia’s senior officials and the CEOs of its largest companies have been on a “non-stop pilgrimage” to China. In parallel, senior Chinese leaders—particularly from the military and security sectors—have made reciprocal trips to Russia over the last four years.

Quantity to Quality

Following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the war has become the single organizing principle for all Russian policy. The Kremlin now assesses every foreign relationship through a simple, three-part lens.

First, how can this nation help Russia on the battlefield? Second, how can it help to sustain the Russian economy and circumvent sanctions? Third, how can it help Moscow push back against and punish the West for supporting Kyiv?

This calculus is driven by the Kremlin’s conviction that Ukraine is only in the fight because of massive NATO support—from weapons and intelligence to direct economic assistance. Since Russia cannot win a direct military confrontation with the superior Western coalition, and has no immediate proxy war in which to support America’s enemies, it must find alternative ways to impose costs on its adversaries.

In these circumstances, the partnership with Beijing is unique. It checks all three of the Kremlin’s boxes in a way no other nation can. Without China, it is highly likely Putin would have found it impossible to sustain his aggression in Ukraine. While Beijing avoids sending direct lethal aid, its indirect support is indispensable. This includes a massive flow of dual-use goods—from “Made in China” drones and their engines to the semiconductors and other critical components that form the backbone of the Russian defense industry.

On the economic front, Putin’s war chest is now heavily dependent on China. Beijing is the primary destination for Russian exports. Financially, the Chinese yuan has become Russia’s de facto reserve currency, keeping its financial system afloat. This is complemented by a flood of civilian imports—like cars and electronics—that keep the shelves stocked and ordinary Russians quiet.

However, a new dimension to the Beijing-Moscow axis is China’s role as a tool for punishing the United States. Before the 2022 Ukraine invasion, this was not the case. Influential voices in the Kremlin urged caution, advising against blindly rushing into China’s arms. They feared that a fragmented global order would pave the way for Chinese hegemony in Eurasia, with Russia relegated to the role of a subservient vassal. Accordingly, before February 24th, 2022, Russia carefully nurtured its own strategic autonomy by maintaining a delicate balance between the U.S.-led West and China. The full-scale invasion of Ukraine destroyed that precarious balance, once and for all.

Convinced in a long-term war with the West that it cannot win alone, Russia has concluded that its only path to victory is to help China dethrone the United States. This change in attitude explains Moscow’s willingness to step up military cooperation and share sensitive technologies with Beijing. For the Kremlin, fully integrating the Russian economy, its brainpower, and its military technology into an emerging “Pax Sinica” is no longer a choice: it is the only sustainable way to pursue its confrontation with the West.

Unsurprisingly, this strategic shift has exacerbated the power asymmetry that defined Sino-Russian relations long before 2022. Beijing, as a larger, more technologically advanced economy with less toxic ties to the West (at least for now as China is not sanctioned the way Russia is), always has stronger bargaining power and more options. Now as a direct result of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russia is systematically locking itself into a state of vassalage. In the coming years, Beijing will be increasingly able to dictate the terms of economic, technological, and regional cooperation. The Kremlin is not blind to this risk, but it has no other choice as long as Putin remains committed to the war in Ukraine.

Chinese foreign policy thinking has undergone a similar, if less seismic, shift. In 2021, Beijing had hoped for a return to a more predictable U.S. relationship following Trump’s disruptive first term. While not expecting a full détente, the goal was a healthier mix of competition and cooperation.

However, the deliberate policy choices of the Biden administration—such as strengthening military partnerships in the Indo-Pacific and imposing comprehensive restrictions on China’s access to cutting-edge U.S. technology—convinced Beijing of the opposite. Hence, China’s leadership has developed a firm conviction that that its confrontation with the United States is now inevitable, regardless of who is in the White House.

This realization has a direct impact on China’s strategic calculus regarding Russia. Immediately following the 2022 invasion, Beijing adopted a cautious approach—withholding lethal weapons, and avoiding massive sanctions violations precisely to avoid American retaliation. However, the sweeping U.S. export controls of October 2022 proved that such a cautious approach was futile. This move convinced Beijing that the U.S. was already committed to limiting China’s military and economic future, regardless of its behavior.

Russia’s importance to China has been solidified through these realizations. Throwing Putin under the bus was never an option, as China fears the instability and potential for a pro-Western regime on its northern border. More importantly, if confrontation with the United States is inevitable, Beijing needs partners to counter America’s greatest strength: its ability global network of resourceful allies.

Having Each Other’s Back

No other power can bring as much to China’s table as the Kremlin. Russia’s rich endowment of natural resources—from energy and metals to agricultural goods and water—supplies China with critical imports at favorable prices. Crucially, Beijing can increasingly dictate these terms and pay in currency that it prints. Additionally, the flow of resources is secured over a long land border with a friendly, nuclear-armed state, which boosts China’s energy and food security. Likewise, this land route bypasses vulnerable maritime chokepoints—like the Strait of Malacca—which are dominated by the U.S. Navy.

While the 145-million-person Russian market is not as large as the U.S. or EU markets, it is a sizable and hungry destination for Chinese goods—increasingly so for Chinese manufacturers. These manufacturers are facing unstable domestic demand and declining exports to the West—a situation made more urgent by Trump’s disruptive tariff war. Furthermore, since the bulk of Chinese trade with Russia is settled in yuan, Beijing utilizes trade relationship as a flagship project for its currency’s internationalization.

Russia also contributes advanced military technologies that China still lacks, despite its own, much larger overall defense manufacturing base. These include surface-to-air missiles, engines for modern fighter jets, nuclear deterrent components like early-warning systems, and technologies for underwater warfare. In addition to hardware, and despite the post 2022 exodus of its talent, Russia still possesses significant brainpower, particularly in IT and engineering, which China can tap.

Military-to-military cooperation is an increasingly important asset for China, particularly as it expands into intelligence and cyberspace. The next logical step is for Russia and China to enhance intelligence sharing and begin joint operations in the cyber domain. As an example, operations could be conducted to steal sensitive Western data and spread disinformation. This marks a crucial evolution: so far, the two nations have worked in parallel—spreading similar narratives independently—but their increased trust could soon enable a more coordinated, tandem approach.

Moscow and Beijing have repeatedly stated that they will not sign a formal military alliance, as neither wants the legal obligation to be dragged into the other’s conflict. However, the de-facto alignment of two friendly, nuclear powers standing back-to-back on the Eurasian landmass presents a major strategic dilemma for the United States. Amidst the collapse of global arms control regimes, American strategists are forced into tough choices on resource allocation. Russia and China’s shared perception of the U.S. as a joint enemy creates an informal pact that enables coordinated moves in both European and Asian theaters, effectively cannibalizing American attention and resources. For example, if Beijing moves on the Taiwan Strait, Russia does not need to engage in the Pacific; a simultaneous, provocative large-scale military drill in Europe would be enough to split U.S. focus and resources.

Moreover, the growing Sino-Russian alignment is set to redraw regional orders, particularly in the Arctic. Before the 2022 invasion, Russia sought Chinese participation in developing Arctic resources on Moscow’s terms. Russia, like other Arctic Council members, actively blocked outside observers like China (a self-styled “near-Arctic state”) from any formal right to define rules in the region. To monetize its natural resources in the Arctic, Russia needed Chinese capital but hedged its bets—balancing Chinese entities with French and Japanese corporate partners.

The full-scale invasion of Ukraine destroyed this strategy. Moscow’s membership in the Arctic Council is on thin ice, Western partners have left under the pressure of sanctions, and the accession of Finland and Sweden to NATO has created a challenging new security predicament. Russia has no option but to rely on Beijing, which is the only partner that can provide the money, market, and technology needed to develop the Russian Arctic. This leverage will put in a position demand favors, including a greater PLA Navy security presence in the region.

In the shared neighborhood of Central Asia, the region’s five republics must navigate between a former colonial master (Russia) and a rising superpower (China). Historically, competition between Beijing and Moscow provided these states with breathing space, allowing them to balance their allegiances.

This led to a complex web of memberships: four are in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (neutral Turkmenistan is the odd one out), while Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan are also formal military allies of Russia in the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO). At the same time, they have begun to develop robust security ties with China. Leading the way is Tajikistan, which has agreed to host two Chinese military outposts. On the economic front, both China and Russia have been important partners, while Kazakhstan and Tajikistan are also members of the Moscow-led Eurasian Economic Union.

However, as Moscow and Beijing move closer, their shared desire to drive the West out of the region is constraining this landscape. Combined with the region’s authoritarian tendencies and a lack of Western bandwidth, all five states are being pushed further into the warm embrace of Xi and Putin.

A Dangerous Example

When Xi told Putin in March 2023, “There are changes happening, the likes of which we haven’t seen for 100 years. Let’s drive those changes together,” he was observing a shift that is less a careful plan and more a raw consequence. While their actions are profoundly altering the global order, they are not guided by a single, well-articulated vision. Rather, Russia and China are simply such large and disruptive players that their individual moves, and their alignment, inevitably change the entire ecosystem.

Both Beijing and Moscow lack a coherent, operational vision for an “ideal” world order. Putin’s attempt to frame his invasion of Ukraine as a rebellion against U.S. hegemonism and “neocolonial practices” rings hollow, given his blatant disregard for Ukraine’s sovereignty and international law. This rhetoric, meant to rally a “multipolar world,” is unconvincing even to the Global South. However, the West is poorly positioned to exploit this hypocrisy. Its own legacy of interventionism, selective respect for international norms—particularly regarding allies like Israel—and a lack of introspection over past misdeeds allows many countries to view the West as just as cynical as Russia.

Beijing’s hypocrisy is similarly plain, with a wide gap between its rhetoric and deeds. This is evident in its muscular advocacy of maritime claims against the Philippines in the South China Sea. The gap is also clear in the “indivisibility of security” mantra, a cornerstone of the February 4th, 2022, joint statement. While Xi and Putin use this to demand the U.S. take others’ security concerns seriously, the concept falls flat against the backdrop of Russia’s total disregard for Ukraine’s security concerns and China’s own bullying of its neighbors.

Hollow words do not change how the world operates, and expanding organizations like BRICS or the SCO does not, by itself, alter the international order. What has had a real and durable impact is the fact that the Sino-Russian partnership has, over the last two years, clearly demonstrated the limits of Western geoeconomic coercion. It has provided a viable blueprint for countries seeking to hedge against dependence on Western technology and the U.S.-dominated financial system. Russia’s experience is the proof: despite unprecedented sanctions it has sustained a large-scale war against NATO-backed state by replacing its massive dependence on the West with a massive dependence on China. This has shown the world that Beijing can provide a credible alternative source of technology, payment settlement mechanisms, and a giant market for commodities.

Helping Moscow sustain its political system and economy—even under the most severe Western geo-economic pressure—is the most significant contribution of the China-Russia alignment to the remaking of the global order. The example set for other countries bears more significance than any of Beijing and Moscow’s proclamations ever could.