- Home

- Horizons

- The New Geopolitics of Energy between Petrostates and Electrostates | What Should Japan and Korea Do?

Nobuo Tanaka is CEO of Tanaka Global, Inc. and a former Executive Director of the International Energy Agency (IEA). He also serves as Chair of the Study Group on Next Generation Nuclear Energy Utilization at the Canon Institute of Global Studies (CIGS) and Chair of the Steering Committee of Innovation for Cool Earth Forum (ICEF).

Nobuo Tanaka is CEO of Tanaka Global, Inc. and a former Executive Director of the International Energy Agency (IEA). He also serves as Chair of the Study Group on Next Generation Nuclear Energy Utilization at the Canon Institute of Global Studies (CIGS) and Chair of the Steering Committee of Innovation for Cool Earth Forum (ICEF).

The energy sector has always been driven and shaped by geopolitics. Japan started a war in the Pacific to secure oil from Indo-China. The International Energy Agency (IEA) was established during the first oil shock, triggered by the oil embargo imposed by Arab petrostates against the United States and several European countries in 1973. Henry Kissinger, a founding father of the IEA, reiterated the mistake of oil-importing countries, saying that we were totally unprepared. The IEA’s strategic petroleum stockpile was accordingly established to address physical disruptions of oil supply. It was released for the first time during the Gulf War of 1991, when Iraq invaded Kuwait. Another release took place at the outbreak of civil war in Libya. The two most recent releases occurred in 2022 in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Military actions involving petrostates often cause supply shortages with oil price hikes. Stock releases worked well to stabilize the situation. Henry Kissinger praised its success at the Ministerial Meeting of the IEA in 2009, saying: “Thanks to its 90-day strategic oil stock requirement and response mechanism, we now have a proven crisis management system that works. It remains our best protection against sudden oil supply disruptions.”

In fact, after the Iranian Revolution in 1979, which triggered the second oil shock and pushed the oil price up threefold to $40 per barrel, the oil market stayed relatively quiet until the early 2000s, thanks to diversification and conservation efforts by consuming countries as well as preparedness exercises of the IEA. Another element contributing to market stability came from global warming concerns. Developed country participants at COP3 in Kyoto in 1997 committed to mandatory reduction targets for CO₂ emissions. Decarbonization policies were mainstreamed, especially in Europe and Japan, which moderated oil demand. On the other hand, China’s economy began growing rapidly after its reform and opening-up policy in the 1990s, and this growth accelerated with its entry into the WTO in 2001. Due to China’s economic expansion, oil demand surpassed supply capacity, and the price hit a historic high of $147 per barrel in 2008. It collapsed because of the global financial crisis triggered by the Lehman Shock. Price volatility has become the new normal since then, driven by geopolitical events, economic crises, and COVID-19.

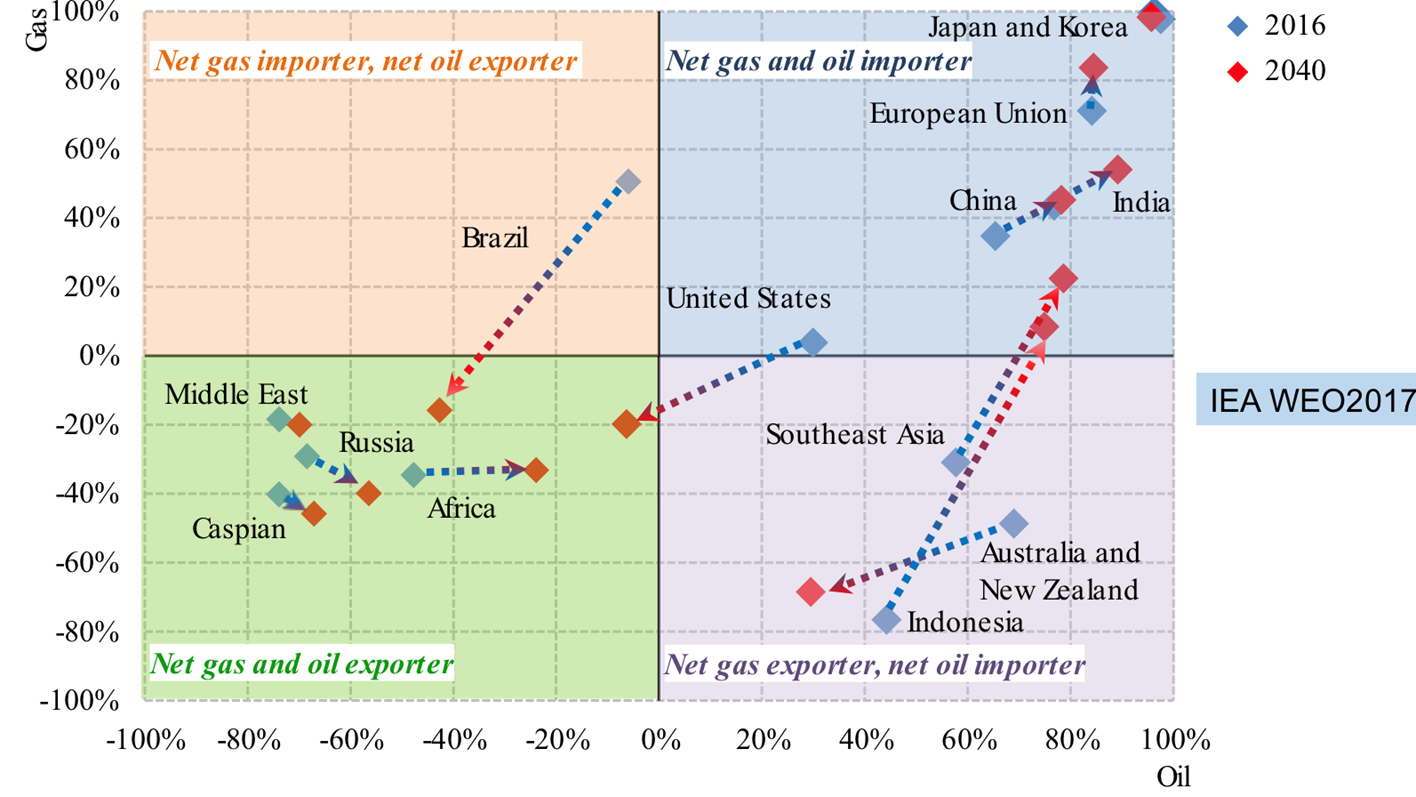

On the supply side, the biggest change has taken place in the United States in the form of the shale oil and gas revolution. The IEA’s chart shows relative position shifts of countries in terms of import dependency for oil and natural gas. The vertical axis represents natural gas import dependency, and the horizontal axis represents oil import dependency. The blue countries are importers of both oil and gas: most of the IEA members, as well as China and India, are there. China and India were expected to rapidly increase oil imports. Henry Kissinger advised me that China and India must join the IEA because their oil imports would eventually surpass those of the entire OECD. As Japan and Korea import 100 percent of their oil and gas, they are stuck at the top-right corner. They can never be worse.

Shifts in oil and gas import dependency, 2016-2040 | Source: IAE/Courtesy of the author

The green countries are exporters of oil and gas: namely, petrostates. The United States has moved from blue to green. Before the shale revolution, the U.S. was expected to move in the opposite direction—up and to the right. In the early 2000s, many new LNG receiving terminals were under construction, but eventually they all turned into exporting terminals.

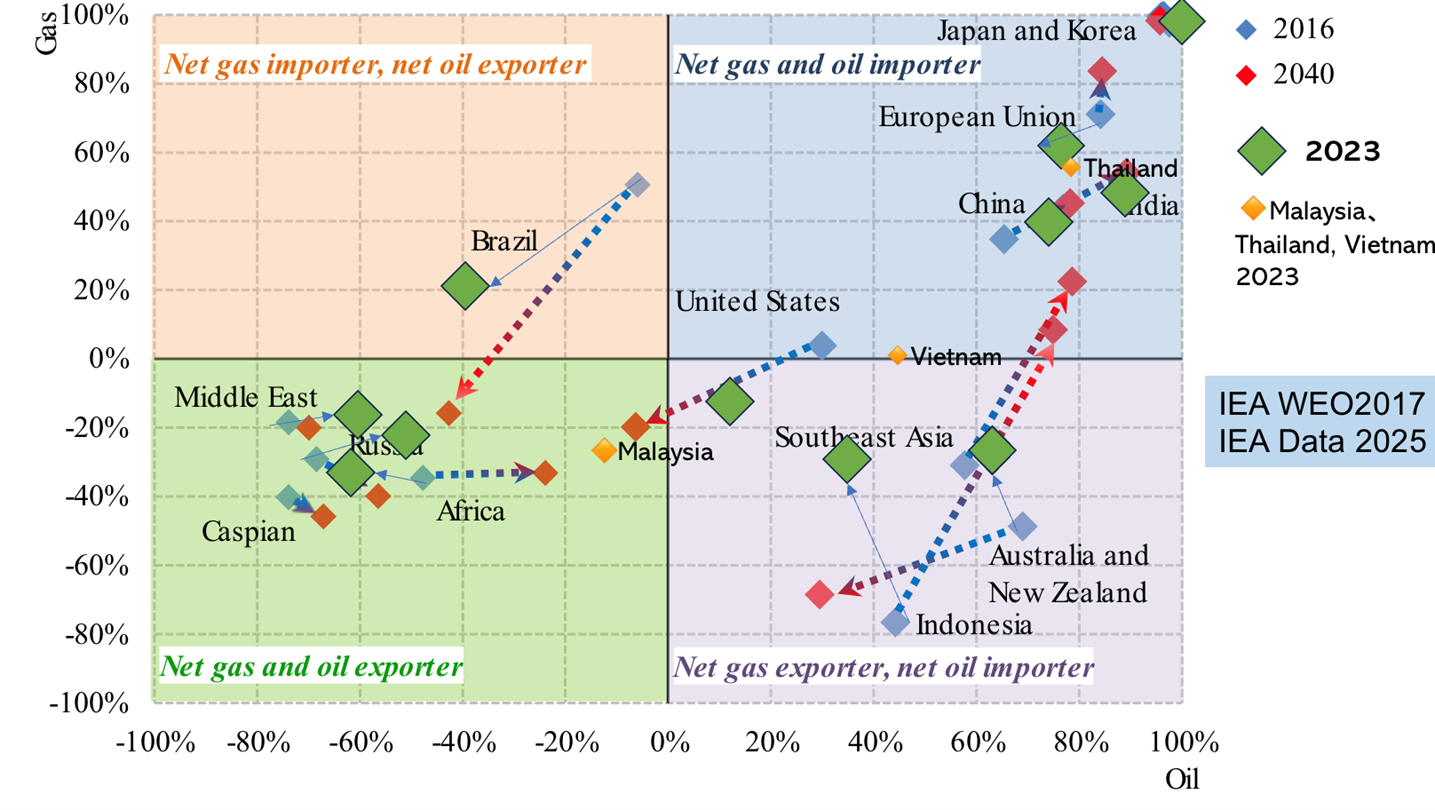

Where do we stand now? I add current positions of countries on the chart as green lozenge shapes. The U.S. is midway and has already become an exporter of gas. U.S. President Donald Trump accelerated the move with his “drill, baby, drill” policy. The United States is moving away from the oil-importing IEA countries and becoming a member of the petrostates. Washington even seems to be forming a coalition with Saudi Arabia and Russia: a new coalition of petrostates. Trump intervened in the battle between Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and Russian President Vladimir Putin during the oil price collapse caused by COVID-19, enforcing joint production reductions among the three largest oil producers. Their collaboration reached the point where Saudi Arabia invited negotiation teams from the U.S. and Russia on Ukraine to Riyadh. Petrostates share the common interest of maintaining energy dominance through fossil fuels for as long as possible.

Current positions of countries in oil and gas import dependency | Source: IAE/Courtesy of the author

China and India occupy the middle ground, as the IEA had anticipated. The EU moved in the opposite direction—downward and to the left. The EU improved its security position by reducing imports of gas and oil from Russia due to sanctions. How, then, do the countries represented in the blue segment improve their security position against petrostates? The answer is through electrification and decarbonization.

Europe and China are leaders of electrostates in the battle against petrostates. China expanded the use of modern renewables more than fourfold in two decades. It is now the global leader in solar panels, electric vehicles, wind turbines, batteries, electrolyzers, and critical mineral refining. China’s electrification rate over final energy consumption is 26 percent and is growing much faster than the global average. In fact, it is expected to reach 35 percent in 2035. Due to extensive use of electric vehicles and rapid transportation systems, peak demand for oil in China may occur as early as 2025. The recent IEA Global Hydrogen Report states that global installed water electrolysis capacity reached 2 GW in 2024, and deployment is expected to accelerate in the near term, mainly due to developments in China—characterized as “China and electrolyzers – the sequel to solar PV and batteries?” The IEA says that China is the only country on track to achieve COP28’s Tripling Renewable Capacity Pledge. China’s electrification strategy through renewables and nuclear power certainly contributes to the mitigation of global warming, and yet its primary purpose is energy security—or “national security” itself. I recall that a former general of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army told me that China is deploying solar, wind, and nuclear power as fast as possible on the grounds of national security.

Europe has long been a leader in renewables for climate change mitigation. When Russia invaded Ukraine, the EU launched the REpowerEU strategy to end import dependence on Russian fossil fuels by relying more on renewables, hydrogen, nuclear power, and diversifying sources of natural gas through LNG. The Chinese and European strategies are the same: strengthening the status of electrostates.

The United States was ranked third in modern renewable deployment until 2021. Even under Trump’s first administration, electrification continued, and it was further strengthened by the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act. Mega-tech firms like GAFAM, as well as blue states, continue to push decarbonization. The current energy transformation has been driven by these mega-tech firms, which require decarbonization of their entire supply chains by 2030—much earlier than governments’ target years of 2050 or later. The transformation has been driven by the demand side rather than the supply side. But Trump is now trying to reverse this trend by withdrawing from the Paris Agreement and cancelling many support measures for decarbonization introduced by the Biden administration. His tariff policy hurts allies more than adversaries. His highly demanding security policy on NATO and Europe is driving Europe closer to China. Europe needs China to face Russian security pressure. Paradoxically, it would appear that Trump is inadvertently solidifying the alliance of electrostates between Europe and China.

India and ASEAN countries follow China and Europe by expanding renewables while continuing fossil fuel use, especially in hard-to-abate sectors. Brazil occupies an interesting position in the previous chart. It is an exporter of oil and may become a gas exporter in the future as well. But it is also a major user of renewables such as biofuels and hydroelectricity. Brazil may join the petrostate alliance but maintains strong leverage as a significant user of renewables. At COP30 in Belém, Brazil used this advantage and dual identity to bridge the gap between petrostates and electrostates, promoting gradual transition language while showcasing its biofuels and hydroelectric base.

In the chart, Russia, Africa, and the Middle East stand out as petrostates without an interest in renewables. But some Middle Eastern countries, like Saudi Arabia and the UAE, are invested in solar and clean hydrogen with Carbon Capture & Storage (CCS). They recognize the possible risk of peak oil demand. I was invited to the board meeting of Saudi Aramco in 2015 in Tokyo. The question I was asked by the chair was when peak oil demand would come. My answer was “before 2030,” because China had already committed to peak its CO₂ emissions by 2030 at COP21 in Paris. And indeed, peak oil demand may be happening in China this year. If decarbonization truly occurs sometime in the future, the Middle East, Russia, and Africa will be the losers caught unprepared—with little to fall back on. There are different views about the rapid growth of renewables: electrostates say it drives “energy transition,” while petrostates say it is a simple “addition” to current energy supply. Who is right, only time will tell, but we had better prepare for both scenarios.

Another player in this battle is megatech firms like GAFAM and Chinese tech companies in pursuit of a hegemonic position in developing Artificial Intelligence (AI) and data centers. Both the U.S. and Chinese governments support their domestic tech leaders. AI and data centers require huge amounts of electricity: currently they account for about 1.5 percent of global power demand, and recent IEA scenarios suggest data centers could use 1.8-3.4 percent of total global power by 2030. In the United States—home to roughly 50 percent of global data center capacity—data centers could reach 6.7-12 percent of total power demand by 2028. Megatechs should be drivers of electrostates. Some regions in the United States where data centers are concentrated are facing rapid increases in electricity prices. In particular, American megatech firms seek decarbonized power for their data centers very quickly. Global competition is beginning over who will receive huge investments. The IEA has analyzed that renewables availability and CCS potential are key elements in determining data center and industrial locations. Where these firms invest may decide who the winning and losing countries will be. Saudi Arabia and Australia may have a good chance to emerge as winners as quasi-electrostates, provided they can host large data centers together with hard-to-abate industrial sectors.

Now the question is: with which side—petrostates or electrostates—should Japan and Korea align? Japan and Korea are importing 100 percent of their oil and gas now, and are likely to continue in the future—they are the most vulnerable in conventional energy markets. Renewable deployment is limited by geographical constraints. They need natural gas as a transition fuel in the foreseeable future. Facing the geopolitical realities of Northeast Asia, Japan and Korea need the U.S. military alliance, including nuclear deterrence. At the same time, however, Japan and Korea are physically close and with profound economic ties to China, with which they need to maintain good business relations.

What should we do? I believe that Japan and Korea should work with both the United States and China in several sectors: Alaskan natural gas, nuclear power, and clean energy—in particular, hydrogen.

Firstly, President Trump’s first-day executive orders included natural resources in the state of Alaska. He mentioned Alaskan LNG exports at his first meeting with then Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba. Japan used to import LNG from Alaska, and gas continues to be an important transition fuel. The Seventh Basic Energy Plan of Japan states that, in the case of slower decarbonization toward 2040 rather than the Net Zero trajectory, Japan will need an additional 20 million tons of LNG imports. Alaska’s proximity to Japan and Korea, without choke points such as those in the Middle East, provides an advantage in LNG supply security. Alaska also has huge potential for wind and geothermal power, which can be converted to green hydrogen. CCS potential is high as well, enabling blue hydrogen. Alaska should be an ideal energy security partner for Japan and Korea.

Secondly, what is sustainable nuclear power? Nuclear power has received a boost in many countries due to increased security concerns following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. More than half of Japan’s general public supports restarting shut-down nuclear power plants. But in reality, restarting has not been completed as expected, because after the tragic 2011 accident in Fukushima, safety concerns have never subsided in surrounding communities. I organized a working group for advanced nuclear systems at the Canon Institute of Global Studies (CIGS), consisting only of women members—except for myself as chair. They discussed the future vision of “sustainable” nuclear power. They concluded with three additional conditions of sustainability: (1) minimum impact of accidents and passive safety features such as Small Modular Reactors (SMR), (2) easy management of highly radioactive wastes, and (3) proliferation resistance. Why did I organize such a group with only women? Because women are much more cautious about the safety and security of nuclear power, and if these women can agree on a certain model of nuclear power, we can create a different narrative for improved public acceptance.

A female president of an investment advisory company with only women staffers once told me that they stopped recommending Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), the operator of the Fukushima NPP, just half a year before the accident. “Why did you do so?” I asked with great surprise. She said that they kept records of all accidents and mistakes of the companies they recommended, and TEPCO kept repeating similar mistakes without ever changing its system. She wondered why other advisers did not do the same. I told her it was because she was running the only women-operated company. My wife remembers all of my mistakes since the beginning of our marriage and reminds me of them from time to time. She does it because she loves me and our family and wants to protect us. If TEPCO’s president had been a woman, she might have avoided the accident in Fukushima. I recommend that if TEPCO wishes to restart the Kashiwazaki-Kariwa NPP in Niigata Prefecture, they should select a woman president and move their headquarters there. TEPCO lost public trust, and they cannot recover it without undergoing extraordinary reform of the company.

The nuclear reactor model that satisfies the three aforementioned sustainability conditions is the Integral Fast Reactor (IFR) of Argonne National Laboratory in the United States. It is passively safe, and its radioactive waste reduces toxicity in 300 years rather than 300,000 for regular spent fuel from light water reactors. It is a closed system with pyroprocessing, and pure plutonium of bomb quality is difficult to separate. Korea is also interested in this technology for solving its waste problems. This technology can be applied to Fukushima’s melted debris. Trilateral collaboration among Japan, the United States, and Korea can solve the most difficult issues of Fukushima.

In the Northeast Asian geopolitical environment, I propose Japan develops a nuclear propulsion submarine fleet together with Korea and the United States, similar to what already exists within AUKUS. We might even call it JA-K-U.S. Japan is not interested in developing nuclear weapons. I hope Korea agrees. We should sign a treaty on the abolition of nuclear weapons while maintaining the nuclear deterrence of the United States. Japan should initiate a new diplomatic offensive by asking for a permanent seat in the Security Council of the UN as a representative of nuclear-weapon-free states. The current monopoly of power by the P5 countries is not fair. The UN should now open the door for non-nuclear states to be treated equally. Otherwise, proliferation is inevitable. I urge India to join Japan, as Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi urges countries to move beyond cold war mentality. To become a leader of the global south, it would be best for him to first be to give up nuclear weapons.

Thirdly, Japan and Korea should develop clean energy collaboration with the rest of Asia, including China. There are different approaches. First, building a supply chain of low-carbon hydrogen. Japan has been promoting the “Hydrogen Economy” for decades, ever since Toyota Mirai, a hydrogen fuel cell vehicle, was first produced. A stylish passenger vehicle cannot create significant demand without refueling stations. Refueling stations cannot be built without enough vehicles. This chicken-and-egg problem deterred the creation of a “Hydrogen Economy.” Toyota should have started with a commercial fleet of taxis, vans, buses, or trucks, which require a limited number of refueling stations. Former Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga broke the impasse by announcing the Net Zero Emissions target for 2050. All industries have taken hydrogen seriously since then. JERA, the largest thermal power company in Japan, plans to co-fire clean ammonia at its coal thermal power plants. Steel industries are developing direct reduction of steel with hydrogen.

The Japanese government recently decided to introduce emission trading and a carbon tax. Green transition bonds of 20 trillion yen were issued to provide subsidies for hydrogen, CCS, and other low-carbon projects. This is a very good first step, but 3 trillion yen ($20 billion) for hydrogen is too small to create a “Hydrogen Economy.” Japan started importing liquefied natural gas (LNG) from Alaska more than 50 years ago. It was a very costly venture, but the regulated power and gas market at that time enabled offtakers to pass additional costs to consumers. Japan cannot return to a regulated market. METI should clearly indicate the future price of carbon to invite private investment. Japan has initiated the Asia Zero Emission Community (AZEC) to create a hydrogen supply chain in Asia. Korea joined Japan’s effort to make LNG a commodity. Now Japan and Korea are joining efforts to build a hydrogen supply chain in Asia in collaboration with China. Clean hydrogen needs scale to reduce current high costs.

Korea and Japan can do more with China. European countries are connecting their power grids and now plan to develop hydrogen pipelines as the backbone of the Energy Union. The EU can solve the volatility of renewables by building a larger energy market. This is Europe’s collective energy security and sustainability policy. Why not do the same in Northeast Asia? Masayoshi Son, CEO of Softbank, promotes the Asian Super Grid. The Global Energy Interconnection Development and Cooperation Organization (GEIDCO) is a Chinese initiative for global grid connection. I chair the Northeast Asia Gas Pipeline and Infrastructure Forum (NAGPF), which is a forum of China, Russia, Mongolia, Korea, and Japan to develop the idea of building a gas pipeline network in Northeast Asia. I am proposing to renew it as the “Northeast Asia Clean Energy Platform,” which would include grid connection and a hydrogen pipeline network. Electrostates should be connected.

Japan has disputed territories with China and Korea. We may jointly build windmills on these islands and connect grids to each other. This would be the first step toward future connectivity. The idea looks visionary. As an example of best practices, it’s worth noting that the EU evolved into its current form by initially creating the European Coal and Steel Community and Euratom after World War II. France and Germany decided to stop killing each other and to manage the tools of war—coal, steel, and nuclear—together. Managing today’s most strategic resource—clean electricity—among electrostates is the first step toward a peaceful Northeast Asian community.

Finally, Japan should start renewed trade diplomacy by expanding the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) agreement. The UK is already a member and the EU seems interested in linking itself to this framework as well. So is Korea, which has shown interest in joining, and so do China and Taiwan. The United States has decided to withdraw but would be most welcome to return. The EU is introducing Carbon Border Adjustment Measures to force trade partners to share the burden of decarbonization. I believe their standards and rules can be best adjusted and applied within CPTPP and that this will eventually become a common green trade zone for electrostates.