Zachary Karabell is an author, commentator, and investor as well as the founder of the Progress Network and host of the “What Could Go Right?” podcast. You may follow him on X @zacharykarabell.

Zachary Karabell is an author, commentator, and investor as well as the founder of the Progress Network and host of the “What Could Go Right?” podcast. You may follow him on X @zacharykarabell.

In a world replete with negative stories, the tenor of opinions about the European Union’s future has been particularly bleak of late. There are certainly reasons to be alert to the challenges and problems: the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the demographic decline now beginning to affect economies and society, and the fracturing of a U.S.-European set of economic and military alliances that seemed inviolable for decades. And yet, however glum and grim the tenor of the time, there are ample reasons to be more positive—even if finding those reasons explicitly and robustly expressed can be as hard as finding a four-leaf clover.

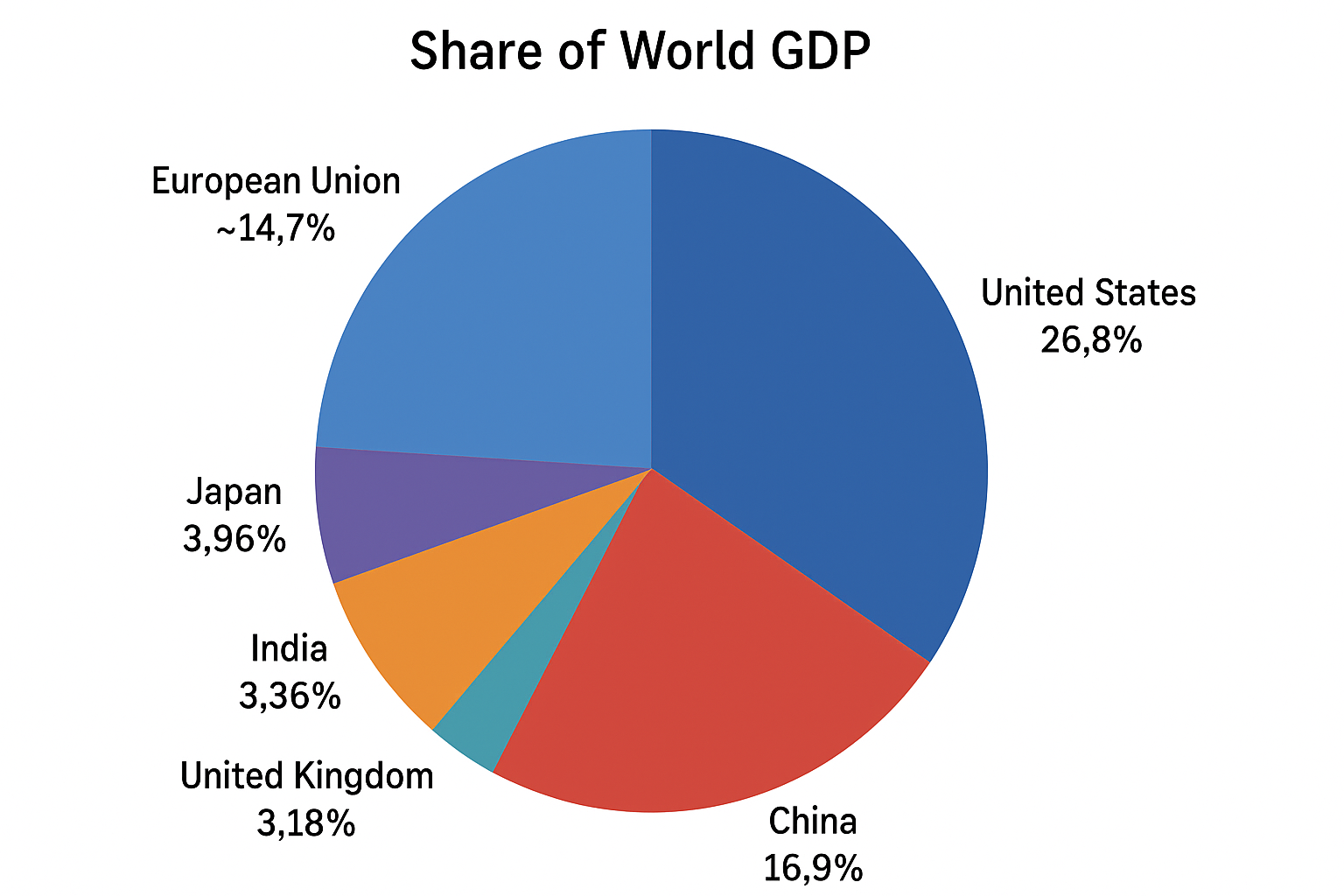

On most metrics, the EU is affluent, stable, and peaceful: the bloc’s present share of global GDP | Source: Sora/Chat GP

Take the recent developments in trade between the United States and the EU. After months of tense negotiation, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and U.S. President Donald Trump met at the latter’s Turnberry golf resort in Scotland and shook on a new trade agreement that would see the EU subject to 15 percent duties on exports to the United States. Some products, such as aircraft parts, will be exempt, while others, such as steel, will face higher duties. That rate is lower than the 30-50 percent tariff Trump initially threatened, but still more than a sixfold increase over what tariffs were in recent years. Moreover, given that the EU exports about $600 billion a year to the United States, the aggregate amount is still considerable. In addition, the EU pledged hundreds of billions of dollars in energy purchases from the United States, as well as increased investment—although it is likely most of those promises simply reflect existing commitments that Trump can present as concessions.

Many commentators and politicians characterized the agreement as a win for Trump and the United States—and as a humbling blow to the European bloc. Von der Leyen weakly touted the deal as “the best we could do,” while some German lawmakers excoriated the agreement as “a betrayal of Europe.” French Prime Minister François Bayrou ominously warned, “It is a dark day when an alliance of free peoples, brought together to affirm their common values and to defend their common interests, resigns itself to submission.”

The reactions in much of Europe played out against the backdrop of the first six months of 2025, during which the United States—led by the Trump administration—has done more to rupture the transatlantic alliance than anyone in the last 75 years (since the end of World War II, the creation of NATO, and the early years of the Cold War). For those who believed that much of that timeframe was positive for Europe and the world—creating an extraordinary period of prosperity—the waves stirred by Trump have been nothing short of a disaster.

And that grimness is, of course, magnified by the ongoing and unresolved conflict in Ukraine. This includes the legitimate concern that Russia, under President Putin—and perhaps his eventual successors as well—is a revanchist country hellbent on absorbing many of the nations that once constituted the former Soviet Union and, before that, the Tsarist Empire.

To that end, one of the subplots of America’s wavering support for Ukraine has been whether the European Union can possibly fill whatever void is left if the United States radically diminishes its military aid. While the recent reversals of the Trump administration seem to have shifted a dynamic that appeared increasingly hostile to Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s government in Kyiv, the future capacity of the EU remains very much in question.

In the past decade, all of this negativity has been consistent with the rising drumbeat that the EU is a dysfunctional organization, masking a deep political and economic malaise besetting most (if not all) of the Union’s 27 member states.

How different it all seemed 30 years ago, as the newly liberated countries of Eastern Europe pulsed with optimism and youth-fueled hope about the future. That was when the new European Union, only officially inaugurated in 1993, began to envision itself as the largest economic bloc in the world, amicably competing with the United States to create a twenty-first-century future of stability and prosperity unlike anything the world had ever known.

Today, those dreams are scoffed at as the naïve hopes of a naïve generation. And yet, much of the economic promise has been validated. In fact, the immigration crisis of the mid-2010s, the security threat of Russia, and the mercurial America of the Trump administration have not structurally changed that. The former Eastern Bloc countries are now richer and more stable by far than they were in the 1990s, as anyone who travels from the Baltics to the tip of the Balkans can see in every city and town along the way.

In fact, the plaints of the EU seem like the dreams of most countries from time immemorial. On most metrics, the Union is affluent, stable, and peaceful. Its 450 million people produce a GDP of nearly $20 trillion, making it the second-largest economic bloc in the world, behind only the United States. Yes, that masks significant disparities between member nations. Moreover, while there is an economic union, it is not as frictionless as between American states or Chinese provinces, and trade barriers (many of them informal and bureaucratic) remain within the Union. Even so, per capita income in multiple countries is among the highest in the world, and almost all the states of Europe (whether in the EU bloc or not) have public healthcare systems that provide universal care of decent quality—well above the global norm and far beyond what was true a few generations past. (Again, one can caveat everything with exceptions, but the generalization remains valid.)

What’s more, almost every European country has low crime rates and high literacy rates; unemployment for the Eurozone as a whole hovers at 6 percent; life expectancy is above 81 years on average. There is a robust social safety net in most parts of the Union, with women near parity in the workforce and an infrastructure for childcare and education. Many of the major cities are routinely ranked as the most livable in the world, with reliable and extensive public transport and clean streets (though in many major metropolitan areas, the cost of living is prohibitive, and zoning restrictions designed by the NIMBYest of “nimbies” make it nigh impossible to build housing or anything new). But few would dispute that, on a global comparison, many of the EU countries are among the most stable and affluent, and offer a quality of life that millennia of humans could only have dreamt of.

Against that backdrop is a chorus of critiques. The EU doesn’t spend enough on collective defense, having depended on the U.S. for security guarantees and on a NATO system underpinned by American budgets and equipment over the last 75 years. The vaunted “interoperability” of NATO forces has been revealed to be a myth since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Granted, anyone in the belly of various defense ministries in France, the United Kingdom, or Germany knew that military systems were not interoperable, and that the mania for each country having its own specific fighter jets, tanks, artillery, and weapons systems would not be so easily plugged and played. As Syria descended into civil war, the Syrian immigration after 2012 saw millions of refugees flood into central and then northern Europe—greeted not with open arms but with an intense nativist backlash, including in formerly open and tolerant countries such as the Netherlands, Sweden, and Germany. Similar dynamics were evident in the face of Libyan refugees arriving in Spain and Italy.

And of course, in Poland and Hungary, democracy and open society have been sorely tested by the rise of semi-autocratic parties. They have been spectacularly successful in Hungary, with its leader Viktor Orbán, and moderately successful in Poland, with the Law and Justice Party. That is the case even though—especially in Poland—the economic formula since the 1990s has been stunningly successful. The increasing momentum for far-right parties such as AfD in Germany, Giorgia Meloni’s coalition in Italy, the Freedom Party in Austria, Geert Wilders in the Netherlands, and the National Rally (formerly the National Front) in France echoes the rise of Trump in the United States. All are fueled by widespread discontent and disenchantment with the governing technocrats of the European Union, and with the same forces of free trade and globalization that have generated backlash across the globe in the face of displaced workers and ruptured communities.

For all the roiling and the handwringing, however, the European Union remains one of the signature achievements of humanity: a multi-ethnic, multi-national political and economic condominium that has helped bring extraordinary stability and prosperity to more than 5 percent of Earth’s population. Here, as in so many walks of life, the fact that narratives of things going well are always trumped by stories of all that is going badly distorts the picture of Europe into a funhouse mirror of dysfunction and disrepair.

The European negatives are clear and understood: the European Commission, which functions as the EU’s main executive body, is intensely bureaucratic and has an unfortunate tendency to micromanage. In its attempt to harmonize standards across the Union, technocrats in Brussels (the capital of the EU) do some laudable things—such as mandating one plug for all electronic devices (the USB-C); however, they also take regulation to the extreme, attempting to define exactly how many gene edits can be done with CRISPR technology before it exceeds some arbitrary number. The pace of new regulations has increased noticeably in recent years, as the Commission tries to keep up with digital and technological innovation, including large-language models and AI.

Yet even here, the net effect has been to reduce barriers to the movement of goods, people, and ideas, and gradually (and sometimes sluggishly) position the Union as a more dynamic place—friendlier to positive change and innovation. The December 2024 report by Mario Draghi, former Italian Prime Minister and ex-head of the European Central Bank, was widely discussed because of its withering critique of the Union as insufficiently focused on future growth and innovation. But the very fact that the report was done and then disseminated can be taken as a sign of an institution that is self-critical, self-reflective, and self-correcting.

If one thing annoys Europeans, it is the assumption that there is a creature called a European—or the idea that one can generalize across so many regions, cultures, and histories. A Greek living in the Peloponnese does not share much in common with a Dane living in Copenhagen, and a French person residing in Lyon has a very different life and cultural baggage than a Romanian living in Bucharest. All true. And yet, the same can be said of an American living in the Mississippi Delta compared to one living in California’s Palo Alto or Parsippany, NJ. There are differences galore, but there are commonalities aplenty.

And one commonality of Europe today is collective security, affluence, and some concord that the state has a vital role to play in assuring health, housing, education—and that collective security. It is the latter that is now receiving urgent attention in the face of a Russia seemingly intent on rebuilding its empire, and a United States seemingly bent on reducing its commitment to the collective defense of Europe. That urgency is a good thing: it shakes up what had been a glacial complacency. It may seem like a crisis, but if so, it is a necessary trigger to get more European states to plan for a less utopian world, even as they continue to strive for one.

On every material metric, the European Union is a stunning success. Even in security—the one area now receiving the most critical attention—the EU and, by extension, the entire landmass of Europe (including non-EU countries such as Switzerland, Serbia, and the UK) has been remarkably peaceful since 1945 (with the stark exceptions of Hungary in 1956, Czechoslovakia in 1968, Croatia, Bosnia, Serbia, and Kosovo in the mid-to-late 1990s as the former Yugoslavia disintegrated, and Russia in Ukraine in 2014 and then 2022). Yet compared to the arc of history, the 80 years since 1945 have been largely free of war and interstate violence between active EU members. Yes, much of that is attributable to the American security commitment post-1945, but over time, it also became an embedded feature of European life and politics in a way that has—and likely will—prove lasting.

If one thing is clear from the present day, it is that humans—or at least humans shaped by modern civilizations—do not fare well with stasis. Things going well does not sit comfortably with the roiling passions of people and societies, and the reality that things can often be better is both an irritation and a spur. Europe today is the apex of what humans have worked for and dreamt of, and yet it is now not enough for the actual humans who inhabit it. Both truths can be true, and both should be honored.