Zhang Weiwei is a distinguished professor of international relations, Director of the China Institute at Fudan University and a board member of China’s National Think Tanks Council.

Zhang Weiwei is a distinguished professor of international relations, Director of the China Institute at Fudan University and a board member of China’s National Think Tanks Council.

The 2024 Munich Security Conference Report was themed “Lose-Lose?,” capturing the erosion of post-Cold War optimism about peace, development, and prosperity. While this diagnosis may hold in the global context, from a Chinese perspective, it speaks to Europe’s current predicament in particular. The Ukraine conflict—a humanitarian catastrophe in its own right—has unleashed crises across Europe: inflation, refugee flows, energy insecurity, economic stagnation, and, most fundamentally, lost peace. These developments have fostered existential anxieties about escalating great power and even nuclear confrontation.

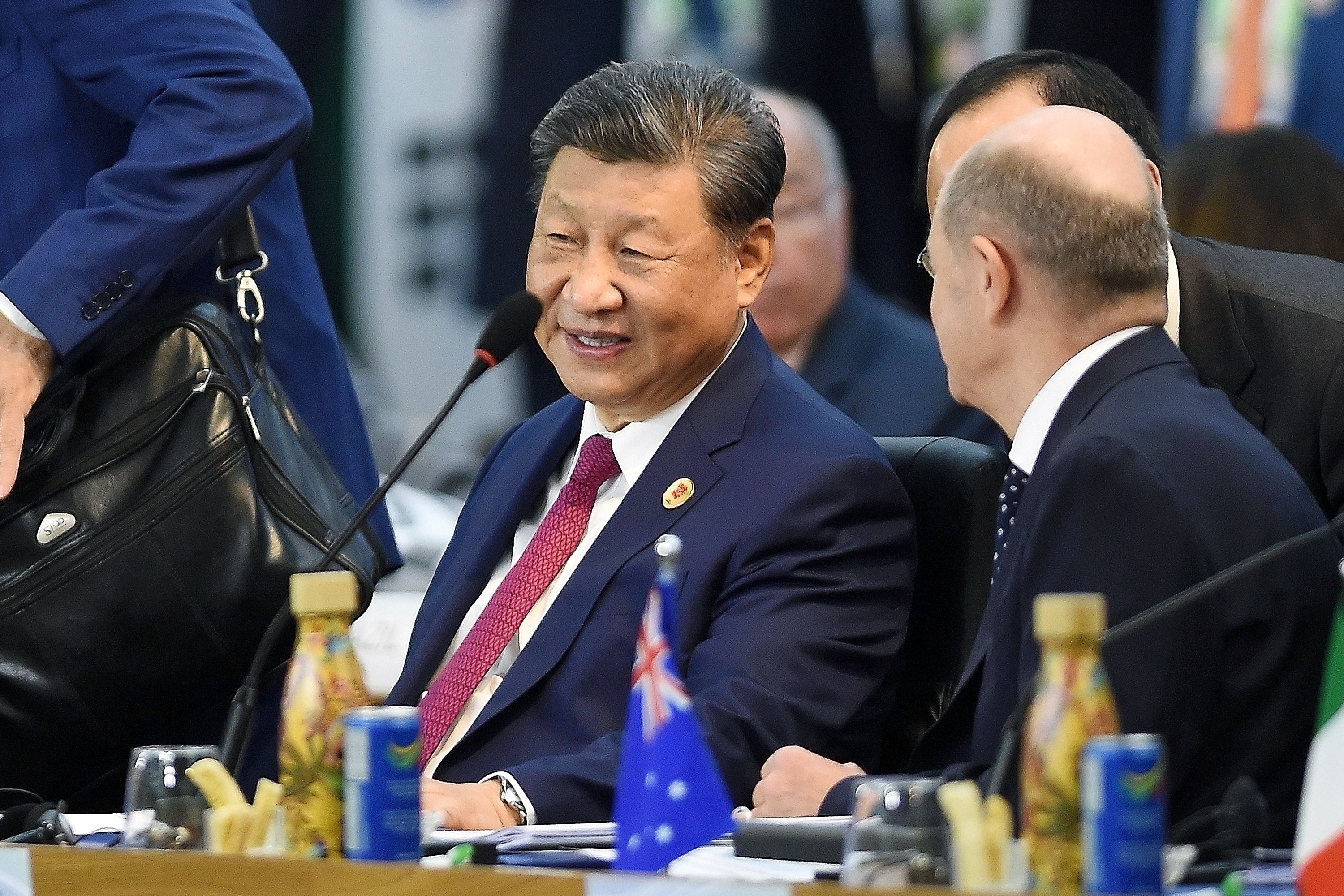

China’s President Xi Jinping in conversation with then German Chancellor Olaf Scholz | Source: Shutterstock

In contrast, the China-ASEAN region—representing 11 countries with over 2 billion people (almost quadrupling Europe’s population if Russia is excluded)—has sustained nearly 50 years of unprecedented peace, development, and prosperity. The historical irony is profound: whereas ASEAN and Chinese scholars once sought inspiration from European integration and security models, today they view Europe’s collective decline with sobriety, raising a fundamental question: What explains Asia’s success while Europe has faltered?

This analysis identifies Asia’s achievement as resting on a “3+1” framework, i.e. three foundational pillars of institution-building (developmental, political-security, and cultural-civilizational) plus China as its key enabler. All of these components merit examination.

The first pillar is development. The China-ASEAN region prioritizes development as the fundamental precondition for peace and prosperity, a strategic divergence from Europe’s more ideological approach. Through five decades of “development first,” China achieved its historic transformation, progressing from a third-world economy to the world’s largest by PPP since 2014 and becoming the leader in industrial output, manufacturing, trade, and technological innovation. This trajectory has generated the world’s largest middle class and China’s average life expectancy is already higher than that of the United States. Today, China uniquely offers goods and expertise across all four industrial revolutions to the world. This economic interdependence in which the U.S. relies more on China for trade than vice versa has largely neutralized the effect of the U.S.-imposed “tariff war.”

Concurrently, ASEAN has sustained long-term growth and stability across most member states despite complex challenges. China has been ASEAN’s largest trading partner for 15 consecutive years, while ASEAN has held equivalent status for China for four, demonstrating their shared commitment to economic integration and mutual advancement. This synergy is sustained by a remarkable common vision to create the world’s largest single market as represented by the China-ASEAN Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), the world’s largest FTA. CAFTA has been upgraded to “3.0” with more focus on the green economy, high-tech development, and supply chain cooperation. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has promoted many regional projects ranging from infrastructure to transportation to the digital economy. Today, this region has collectively become the global epicenter of economic expansion, and China and ASEAN contribute about 30 percent and 10 percent, respectively, to global growth over recent years.

The second pillar is politics and security. ASEAN has established a distinctive approach through its principles of “ASEAN centrality” and “ASEAN neutrality.” This political framework maintains strict non-alignment, avoids great power partisanship, and has developed sophisticated multilateral security and other mechanisms such as the 10+1 (China), 10+3 (China-Japan-South Korea), and 10+8 (including the United States, Russia, India) dialogue platforms. As the first major power to accede to the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia, the first to establish a strategic partnership with ASEAN, and the first to endorse the Southeast Asia Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone protocol, China has reinforced ASEAN’s leading role in regional cooperation.

Western critics typically characterize ASEAN’s consensus-based model as institutional weakness. However, as noted by senior Singaporean diplomat Kishore Mahbubani, ASEAN’s paradoxical power emerges precisely from this perceived limitation: “Its strength lies in its weakness. This explains why global actors universally trust ASEAN—evidenced by the full participation of world leaders in the East Asia Summit. No power feels threatened by ASEAN, granting it unparalleled convening authority in regional affairs.”

The third pillar is the cultural-civilizational focus, which forms the philosophical foundation for the China-ASEAN community of shared future. This framework emphasizes distinctive Asian political traditions and successful practices such as strategic patience in conflict resolution; negotiated settlements for territorial disputes; the art of informal diplomacy; the gradualist approach of “two steps forward, one step back”; and the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, perhaps the most important intellectual heritage originating in the 1955 Bandung Conference. Indonesia, ASEAN’s largest economy, has particularly enriched this tradition through its indigenous concepts of musyawarah (deliberative consultation) and mufakat (consensus-building), now permeating ASEAN’s decision-making process. This civilizational paradigm consciously rejects Western liberal hegemony and NATO’s attempted expansion into Asia.

Indeed, the above three pillars have transformed the whole region. Southeast Asia, once considered Asia’s “Balkans,” due to its fractious diversity of ethnicities, religions, and political systems, has turned its “geographic curse” into a geographic blessing. This transformative model now extends to Central Asia through BRI connectivity projects, converting that landlocked region’s historical isolation into a strategic centrality through overland corridors linking Chinese and European ports. Indeed, Southeast Asia and Central Asia are now gradually transcending traditional geopolitical constraints to forge what may be termed an emerging geo-civilizational order.

In this context, one may better understand Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s three global initiatives for development, security, and civilizations respectively, which have drawn upon the successful experiences of China, ASEAN nations, and other partners, embodying the Chinese vision for a more just and representative “win-win” world order for the future.

The contrasting outcomes between win-win Asia and lose-lose Europe stem in many ways from the different roles played by China and the United States in each of the two regions. Analyzing the philosophical, cultural, and behavioral differences between China and America (and extrapolating to European or Western ones in general, as many Europeans still view America as the leader of the West), may well explain how Asia and Europe fare today while offering valuable insights into what a possible new international order may look like. The main differences are evident:

First, China is a civilizational state, i.e. an amalgam of the world’s longest continuous civilization and a huge modern state, and it is also described as baiguozhihe or “an amalgam of hundreds of states into one over its long history.” The so-called Thucydides Trap projected by Harvard scholar Graham Allison assumes that a rising great power and a status quo dominated by an existing great power are bound to conflict or even result in war.

Yet, as a civilizational state, China possesses unique traditions that are far more inclusive and long-range in overall thinking than in American culture. For instance, Americans have a mentality of treating other countries as “friends or foes,” while the Chinese treat others as “friends or potential friends.” This difference is rooted in vastly different religious traditions, and the Chinese ones are far more inclusive and syncretic than the European or American ones. This also explains why there was an almost total absence of religious wars in China’s long history compared with Europe’s protracted religious conflicts over centuries. In China, Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, and more have co-existed well and drawn on each other’s strength. This absence of religious wars was a source of inspiration for many European Enlightenment giants such as Voltaire, Leibniz, and Spinoza.

Second, along with its inclusive and syncretic culture, China neither has a messianic tradition aiming to convert others nor a militarist one for conquest, as do the Western powers. After all, China is a country that built the Great Wall to ward off aggression instead of provoking it to conquer other countries. Even when Chinese military might was much greater than Europe’s, when Admiral Zheng He led numerous overseas voyages in the first half of the fifteenth century, he traded and did not colonize others, unlike Chrisopher Columbus nearly a century later.

Third, this tradition has been reflected in the difference of state behaviors between China and the United States. When the U.S. became the world’s largest economy during the 1890s, it launched a war against Spain and occupied the Philippines and Cuba. In contrast, while China became the world’s largest economy in 2014 (in PPP terms) and has developed the military capacity to easily take back all of the occupied islands in the South China Sea today, it has chosen not to do so and prefers a negotiated solution to territorial disputes with its neighbors. Upon testing its first nuclear device in 1964, China declared that it will never be the first to strike, nor will it ever use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapon states. Of all the major powers, China has perhaps the highest threshold for the use of force, a tradition originating from Sun Tzu’s renowned caution for prudence in the use of military force going back two millennia. China has not fired a single shot throughout its extraordinary rise over nearly half a century.

Fourth, the Thucydides Trap thus does not apply to China. In fact, the 16 cases cited by Allison in his book are all from European history or countries such as Imperial Japan, which had been strongly influenced by extreme Western militarism after the Meiji Restoration. Yet, as a civilizational state, China has built up a formidable modern defense capability, including powerful nuclear deterrence, and the country has established clear red lines which no foreign country can cross. It’s also worth recalling that while the Cold War was “cold” between the U.S. and the USSR, it was hot between the U.S. and China over the Korean battlefield in the early 1950s and the Vietnamese one in the 1960s when China’s red lines had been crossed—a lesson that the U.S. should bear in mind.

It is useful to note that amidst recent tensions between the U.S. and China, U.S. Secretary of Defense Peter Hegseth acknowledged openly that China’s hypersonic missile system is capable of destroying all American aircraft carriers within 20 minutes, and that in all its war games over the past decade, the U.S. lost to China. In this context, I have long advocated the idea of “Mutually Assured Prosperity” (MAP) for better Sino-American relations to replace the outdated Cold War notion of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD). One can only hope that MAP will replace MAD sooner rather than later.

Having discussed Asia’s win-win model and its three foundational pillars alongside China’s enabling role, in contrast to Europe’s position with respect to the United States, it’s high time for Europe to reevaluate its American relations. To do so, Europe must face its own many problems first and foremost. We live in a transformative time that calls for courage and transformative ideas, and lessons from Asia could offer a helping hand.

Lesson One: state sovereignty and regional autonomy are the hard truth without which Europe’s future will be dim. China, in partnership with ASEAN, upholds their individual sovereignty, sovereign equality, and development-centric sovereignty (“avoiding external interference”) in sharp contrast to Europe’s dependence and willing submission to America’s dominance in European affairs. Now with U.S. President Donald Trump back in power—from MAGA’s illiberalism and isolationist trade practices to wavering NATO commitments—Europe’s vulnerability has never been so exposed to the whims of Washington. Europe’s self-identity as America’s ideological ally and primary security collaborator only serve to perpetuate Europe’s vassal status and hence its multiplying vulnerabilities. Europe needs a real foreign policy, as China and ASEAN do, to protect its own interests and dignity instead of subserving to Washington or trying to meet Donald Trump only halfway.

Asia’s prioritizing of development as the foundation of peace and prosperity is also part and parcel of its philosophy of state sovereignty and regional autonomy, which is particularly important today as a new tech revolution sweeps the world. Meanwhile, Europe following the U.S.’s politicization of economic relations will lead to nowhere. The lamentable fate of German Industry 4.0, a blueprint conceived to develop Germany’s smart manufacturing, is a telling example. Berlin followed Washington’s dictate to ban Huawei’s 5G technology under the flimsy excuse of national security, leading directly to the plan’s failure after rejecting the best available technology for smart manufacturing. In contrast, inspired by the German plan, Beijing drafted and successfully executed its Made in China 2025 Plan, and the country is moving quickly into an AI-empowered digital economy and smart manufacturing. China now leads the world in 57 out of 64 areas of critical technologies according to a recent study conducted by ASPI, an Australia-based think-tank.

Lesson Two: China-ASEAN political and security mechanisms rest on two cardinal principles:

-

regional autonomy through non-aligned diplomacy and rejection of external power domination;

-

inclusiveness to cover all regional actors and global stakeholders with ASEAN in the driver’s seat.

In comparison, neither of these mechanisms seems to exist in Europe nor in its relationship with the United States.

This Asian framework has maintained regional stability and prosperity despite many overlapping territorial claims and other disputes in the region. The 2002 Declaration on Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea exemplifies how diplomatic patience and multilateral consultation prevent conflict escalation, even with the troubled relationship between the Philippines and China. In comparison, European security exhibits its overdependence on U.S.-dominated NATO for hard power and on its philosophy of “keeping America in, Russia out, and Germany down.” This confusion of Europe is a huge mistake, and a European security framework excluding Russia—a permanent Eurasian power—is unthinkable to most Asians or to all those with slightly more historical memory and longer geopolitical and diplomatic visions. Europe should talk to Moscow directly as Russia is its permanent neighbor, an unchangeable geographical and geopolitical reality solidified by the Ukraine conflict.

Lesson Three: a coherent approach to comprehensive security is essential for both national and regional security. Europe’s energy self-sufficiency stays only around 40 percent, much lower than China’s, yet Europe does not have a consistent and all-encompassing security strategy. NATO’s eastward expansion proceeded without consideration for Europe’s energy security, yielding enormous negative consequences for the European economy.

By contrast, China-ASEAN economic cooperation demonstrates how strategic energy partnerships can sustain regional growth and solidarity. China’s “development first” places energy security in the context of its comprehensive security strategy, and the country has succeeded in reaching an energy self-sufficiency rate of 85 percent by 2024 through both cleaner fossil fuel utilization and the dedicated development of the world’s largest renewable energy production capacity. With abundant renewable resources, ASEAN members are now the main beneficiaries of China’s green economy and technologies. The recently concluded China-ASEAN FTA 3.0 prioritizes cooperation in green economy and energy security. China’s energy sufficiency has also reduced its dependency on the Strait of Malacca.

Likewise, comparing Europe’s Green Deal with China’s green energy transition serves as another case in point. Though Europe launched its Deal much earlier than China with great fanfare, its effort has been derailed by NATO’s eastward expansion and its predictable consequences such as the Ukraine crisis. Yet in the case of China, its green deal is now complete, with China’s CO2 emissions peaking by the end of 2023, while its economy (the world’s largest by PPP) has simultaneously maintained a robust 5 percent annual growth rate. In other words, China has contributed more to world growth than all G7 members combined as its CO2 emissions have declined. Now the green economy and related technologies have become a powerful engine driving China-ASEAN’s cooperation and development.

Lesson Four: cultural and civilizational dialogues based on mutual respect are indispensable for win-win regional integration and beyond. The European political establishment’s faith in and practice of liberal hegemony and interventionism have proven strategically myopic and deeply resented across most Global South countries. Now a “color revolution” has occurred to the West itself with Trump now in power, championing illiberalism and “America First” ideology. As a result, Europe’s weakness both in hard power and soft power is further exposed. In retrospect, Europe should have drawn lessons long ago from the transformation of the Arab Spring into the “Arab Winter,” which I predicted back in 2011 in a much-publicized debate with Mr. Francis Fukuyama, the original author of the “end of history” thesis. The Arab Winter has now left Europe grappling with an enduring refugee crisis and its deep ramifications. Even Trump has realized the exorbitant cost of value-driven foreign policy, and the transatlantic ideological project to establish Western-style democracy internationally now faces terminal decline, not because its values were necessarily “wrong” but because of its universalist pretensions which ignore the world’s civilizational diversity.

Unlike Asia’s civilizational dialogue architecture, Europe’s moral absolutism has left it overextended abroad and deeply divided at home and within the Western world overall. The European civilizational crisis stems from its paradoxical position: while promoting supposedly universal values, it fails to recognize their deep-rooted Western biases and contingent origins in the eyes of most other countries. The liberal West has long preached universal values, claiming they are neither Western, nor European, nor Judeo-Christian. However, as political scientist Bruno Maçães observes, “the liberal West” is now dead, having caused “a global rootlessness” while some advocate a return to Europe’s Enlightenment. Still, it was Enlightenment liberalism with its universalizing tendencies that led the West to its current dilemma, which has severed the West—and Europe in particular—from its own cultural roots. Maçães notes “Western societies have sacrificed their specific cultures for the sake of a universal project.” Indeed, a culturally, socially, and politically divided West still faces an uphill battle to develop a common civilizational identity, not to mention a civilizational state.

Lesson Five: recalibrating E.U.-China relations will be uncomfortable for Brussels but remains essential for Europe’s long-term interests. While Europe became rightly critical of the Trump administration’s wholesale dismantling of the rules-based international order that the U.S. long championed, Brussels now demands China to conform to the same selective interpretation of that order. This particularly concerns its relations with Russia, placing blame on Beijing for the Ukraine conflict. Such an approach understandably generates resentment from Beijing and the Chinese public, who view these demands as hypocritical and disrespectful toward China’s sovereignty.

As mentioned above, a majority of Chinese people believe that NATO’s five rounds of eastward expansion, actively supported by European countries, constitute the primary cause of the Ukraine crisis. Moreover, numerous prominent figures including George Kennan and Henry Kissinger had repeatedly warned that such expansion would serve as unnecessary provocation against Russia. Many observers in Beijing expressed surprise at Russia’s prolonged tolerance of these expansions. As far as China is concerned, it firmly opposes any NATO expansion into Asia and will take any and all necessary resolute measures to prevent it.

In the end, Europe’s entrenched biases toward China stem from a longstanding perception framework dominated by ideological and geopolitical prejudices alongside a deeply rooted Western tradition of viewing global affairs through binary lenses: black or white, right versus wrong, democracy versus autocracy, and zero-sum outcomes. A civilizational state like China is free from this kind of straight-jacket, and it has gained so much from the wisdom of “friend or potential friend” rather than “friend or foe,” of “unite and prosper” rather than “divide and rule,” and of “one humanity.”

China’s independent development trajectory continues its rapid advance regardless of European recognition. Should Europe persist in its ideological biases and confrontational approaches, it may well end up in self-isolation from the world’s most vibrant and dynamic region, including its economic and tech ecosystems alongside its central role in the irresistible global trend towards a new multipolar global order. As China speeds ahead like a bullet train, it needs not wait for Europe to wake up. It’s now or never for Europe to make up its own mind, and some sober lessons from Asia may indeed prove instructive.