Edi Rama is the Prime Minister of Albania and Leader of the country’s Socialist Party. A former Mayor of Tirana, he is Albania’s longest-serving democratically elected leader. You may follow him on X @ediramaal. This interview was conducted on July 8th, 2025.

Edi Rama is the Prime Minister of Albania and Leader of the country’s Socialist Party. A former Mayor of Tirana, he is Albania’s longest-serving democratically elected leader. You may follow him on X @ediramaal. This interview was conducted on July 8th, 2025.

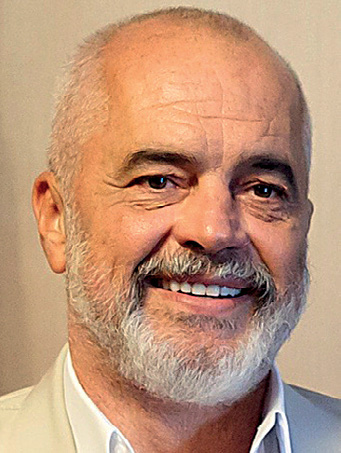

In this edition of Horizons, devoted entirely to the future of the European Union and the broader European continent, we present an exclusive interview with Albania’s sitting Prime Minister, Edi Rama. A remarkably versatile figure—artist, former professor, and basketball player—Mr. Rama is widely regarded as arguably the most successful leader in Albania’s democratic history. Over the past several years, he has steered his country through a period of dynamic growth. In an in-depth conversation with Horizons Editor-in-Chief Vuk Jeremić, Mr. Rama reflects on Europe’s complex, and in some aspects escalating, crisis, warning that attempts at “transforming Europe from a peace project into a war project is very dangerous,” and questioning how its leaders could forget that the continent’s “main power is in its soul and not its muscles.”

Our idea for this issue of Horizons is to talk about the future of Europe. Let me thus start by asking you, Mr. Prime Minister: do you believe that Europe is in crisis—some would say even in an existential crisis? And if you believe that Europe is in crisis, how would you define it?

Vuk Jeremić and Edi Rama during the interview on July 8th, 2025 | Source: CIRSD

If we speak about Europe as our continent and not just as the European Union, I strongly believe that our continent is in an existential crisis, which is related to many factors, but one that has become very visible after the Russian aggression in Ukraine. Since then, the division has become disruption. On top of that, since then, we in this part of the world have realized how much the world has changed. This realization came not just through reading or the forecasting of many commentators, but through facts—through how real this new world with different emerging powers is, and how differently so many actors on the world stage think from us. So, on the EU’s side of the continent, the European Union has been, for quite some time I would say, sleepwalking—continuing to treat the future as a routine and continuing to do business as usual while things were radically changing. So, we are in a very interesting moment. As much as this is a crisis, it is also, I believe, a very big opportunity.

You’re saying that it was the Russian action in Ukraine that woke everybody up, but regardless, the dynamic changes that you were describing in the whole world had already been taking place. Do you think that European leaders or institutions were aloof or dormant regarding those?

I would say that it was not just Europe but also the American side of the story that has contributed to this attitude based on self-referential thinking. The so-called “moral compass,” “moral supremacy,” and the system of “undisputable values” have made their own impact and have somehow relativized events to the point that everything that was happening came to be seen as not so relevant. I don’t know if you agree, but somehow my sense was that it was even somewhat surprising when the so-called collective West reached out to others, looking for a very broad alliance of countries to condemn Russian aggression, and it was very difficult. And somehow it didn’t work. In a way, it was very obviously anticipated. All this has unfolded exactly in the ways we have seen throughout history when periods of decline were treated as periods of stability.

Well, it’s fascinating because you recently hosted the European Political Community Summit here in Tirana. And what’s your impression? What did you learn from that experience, seeing all the European leaders, and what did this tell you about Europe’s capacity for future cohesion? Do you believe that the European Political Community is something that has a great future—are you optimistic in this regard? Or, as some people say, from time to time, France comes up with these grandiose ideas like the Mediterranean Union, and then after a few years it just fades away.

The European Political Community is, in my eyes, a fascinating idea. Of course, it is an idea that has been promoted time after time by French presidents. Mitterrand had a similar idea. Sarkozy too. Macron came out with this European Political Community, which, in the beginning, encountered some soft hostility from the Germans because it was seen as an alternative to EU enlargement. Of course, France is not the most enthusiastic of countries when it comes to enlargement, and we know that. But I believe the European Political Community is more than that. If you go back to its roots, it’s much older and, at the same time, so visionary. It’s so shocking when you see it with the eyes of actuality—when Charles-Irénée Castel, abbé de Saint-Pierre, put it in writing and predicted finding perpetual peace by creating a federation of countries that would also include Russia and what, at that time, was an important part of the Ottoman Empire. Going from that moment in history to the present day and seeing how controversial both the issues of Russia and of Turkey have been, you realize that, in the end, there have been some difficulties in overcoming the Cold War and the religious and cultural impediments. At the same time, you also realize that although we might have every reason to despise the way Russia is governed, Russia is not going to go anywhere. On the other hand, you also realize that Turkey cannot just be cut out like that. Perhaps, unlike Russia for the time being, Turkey has shown just how important it is for the security of Europe and for the great new challenge of illegal migration. Therefore, the bottom line is that the European Political Community is a healthy thing that needs to be deepened, further articulated, but is nevertheless one that I believe has a future. To answer your direct question about what I sensed from the last summit—it is that, unlike the previous ones, the need to react, the awareness of the need for Europe to wake up, and the desire to move and shape the boat were much more tangible. Definitely more tangible than two or three years ago. Will Europe, with the EU to begin with, be able to overcome this moment remains to be seen. For the time being, I feel like there is an effort.

There is definitely an effort, and most discussions about the future of Europe now revolve around what is essentially a rearmament effort—spending much more on defense. At the same time, Russia is surviving, economically speaking. Not too many people expected they’d be able to survive the sanctions and being cut off from their traditional energy partners and markets in Europe, but Russia turned into a war economy. Aren’t you afraid that if the plans to beef up European defense are successful—worth hundreds of billions of dollars, if not more—you will end up with two hostile actors on the continent, both with war economies next to each other while not maintaining too much communication? Are you afraid that this may create a strategic dynamic that makes another major war on the continent possible in our lifetimes?

We had a NATO summit in June, and I shared what I’m saying now with the summit, just as I did during the summit of the European Political Community, without going into the merits of such a decision. While I am the tallest among all the leaders of the European Political Community, I am fully aware that I represent a very small country and don’t pretend to be able to influence or act in different ways than what the big guys decide. Albania will fully comply with what the big guys decide. I’m fully aware that our sovereignty is limited when it comes to big families like NATO or the EU, and this goes not just for Albania but for a lot of countries of modest size. My point of view is that transforming Europe from a peace project into a war project is very dangerous, and is something that should be reflected upon sooner rather than later. Maybe we need to invest more in our defense. On the other hand, how can Europe possibly forget about diplomacy? How can it forget that its main power is in its soul and not its muscles? It is in its light and not in its capacity to fight darkness with darkness. I have said it before, and I keep saying that it’s a time when the Secretary General of NATO should also be encouraged to talk to the other side—the Russians, the Chinese, or whoever else. We can’t live in a place where we are not able to trust that there is some humanity, even in one’s worst enemy. As you said in your question, if we rearm and keep building up, what we build up is, by definition, the capacity to be hostile. We produce, produce, and produce. And it’s not the type of production like vegetables or art that people can consume. We fill all the warehouses, and we build even more to store the ammunition. What’s next? Europe cannot become a war project.

And, on the other hand, to say it all—how come we needed Donald Trump to rediscover a very simple word like “ceasefire?” When Viktor Orbán mentioned ceasefire, he was treated like scum. Without going into the conflict between the EU and Hungary or Orbán himself and the EU, it’s worth asking: how come that when Donald Trump mentioned ceasefire, suddenly everyone was running to jump on the winner’s carriage? Why did we need Donald Trump to talk to Putin, and what does it mean? Because maybe I’m wrong. For sure I’m wrong, because I’m not someone who pretends to know history very well, but I don’t know another war in which there was no backchannelling at all, as is the case with this one in Ukraine. While Israel and Hamas kill each other all the time, they never stop talking. They never stop going back and forth to Doha to talk. How come no one has talked to the Russians for such a long time except Erdoğan and Turkey, which invites the question of what we are doing here? A war of extermination? We should not forget that this is not World War II. We are in an era of nuclear powers. It’s very puzzling, and I believe that we can do better than that and are better than that as Europeans. We need to reflect and understand that putting ourselves on the American autopilot does not necessarily equal making the right choice for Europe. Picking sides is okay, since you have to pick sides when there is a moral choice to be made. But, on the other hand, Europe cannot be a teenager that sides with Mama and never talks to Papa—or the other way around.

Papa presumably being Trump. At least we are led to believe so.

Well, whoever. For three years of war, we 100 percent stood with what was a very clearly defined American line without questioning it and without trying to do anything but double down. Now, suddenly, there is a newcomer in the White House who comes out and talks to Putin and wants to have a ceasefire. And we are then surprised and seen complaining about being left out and saying that we want to be part of the process at the negotiating table. I believe that the table for the conversations, negotiations, and other relentless efforts should have been a European table. Of course, this doesn’t mean giving up. It doesn’t mean recognizing the right to disrupt international law or relativizing aggression against a sovereign country. It doesn’t mean not standing with Ukraine, but it means always giving peace a chance, as John Lennon would say.

I know what you mean. You mentioned Trump and how suddenly the change from America came about with the transition from one administration to another. America is another place where one can discuss whether it is in crisis, given its internal polarization and the vigor of American political debate. Let’s talk for a second about the future of the U.S.-European relationship. We know for a fact that things can change very significantly overnight in terms of trade policy, attitude towards common security, and America’s future preoccupations with other parts of the globe—especially the Far East. How do you project Europe’s future cohesion and attitude toward its principal ally, the United States, which is obviously going through certain political, cultural, and technological convulsions?

Again, I would always start with Europe and not with external factors that can fluctuate or manifest themselves in different ways due to a variety of reasons. The main question is what Europe wants to do and how it wants to grow up in a world in which others are growing up—and fast. There are so many questions that we need to answer, beginning with how much Europe we have today, how much (of their national egos) the EU members are prepared to sacrifice to make the European Union more of a union and less of a federation of egos that sometimes makes it impossible to even issue a declaration about relatively unimportant matters. Then, what is going on with public opinion, especially in older European societies? How is politics in Europe changing, and what might it become in the near future? What is the impact of the extremes, the far right, especially its end goals? I have a problem with this reality being dismissed easily by saying that they are the problem. No, it’s not them—the problem is the problem. Deal with the problem first and then deal with its reflection, because they reflect what is already going on in society. They might be generally very good at demagogy, but the raw material for their ascent is found in society. Europe has to deal with both the fast-changing external world and a new geopolitical reality on the one hand, and with its internal physiological problems on the other, which have to do with the way Europe works—starting from the fact that we have about 27 doctors dealing with a single patient.

There is another significant geopolitical actor—some would say the second most relevant in the world, or perhaps one that is on par with the United States. I’m obviously talking about China. It has enjoyed exceptionally dynamic growth and development, especially in the field of technology and in most fields related to sustainability, which is, in many ways, key to the future of China’s engagement with Europe. Europe seems to be struggling in relations with all these big geopolitical actors: with Donald Trump on the discussions on trade, and with Russia due to a lack of discussions about the future of security and energy, for instance. And then, when it comes to technology and the very ambitious European goals set for the green transition, we find ourselves in a situation in which it is very difficult to imagine how the transition can be carried out without comprehensive technological engagement with China, which is the world’s number one power in that particular field. At the same time, there are increasing concerns in certain parts of Europe about engaging with China in those strategic sectors. What is your view of the future of China-EU, or to make it broader, China-Europe relations?

My understanding is that, among all the players, China is the one that has a particular luxury that others don’t. This is the luxury to think about the next 100 years, not about the next two or four years, elections, or by-elections. On the other hand, I don’t wish to sound like someone praising an undemocratic system, but I want to say that the way China has made a stunning comeback as a main global player, after having been one from the first to the nineteenth century, is incredible. This is impressive in the sense that they have adapted their millenary culture to the new era and combined their one-party system and the Communist Party ideology with their tradition. It’s a country where it’s not the party but the tradition that imposes the rule of no interference of business leaders in political decision-making. For thousands of years, the Chinese have kept a very unbreachable dividing line between politicians and businessmen, and this has now become part of their new system. It’s impossible to imagine an oligarch in China. It’s impossible to imagine someone who, due to the driving powers of capitalism, can possess the wealth and a variety of tools to affect the decision-making of the country to the point of being able to determine who runs it.

There is another key factor that makes China very different, which I’m mentioning for the sake of efforts to understand China better and learn how to deal with this unavoidable player: unlike other empires and great powers, China has never had the impulse to universalize its way of being, thinking, or acting in the world. They are not looking to make the world communist, which used to be the delirium of the Soviet Union or the whole former communist empire that collapsed miserably. Even in the way of conducting their own affairs, they have this double yin and yang system where communism and capitalism work in concert, and the Communist Party operates like a board running the affairs of a capitalist corporation. That being said, it’s important for Europe to find a way of being consistent. The other thing that I think has damaged bridges with the world has been the inconsistency. Look at the way we treated Russia after the Cold War. It has not been consistent, and at a few moments, Russia was seen and treated exactly like the Soviet Union. At other moments, the country was seen as a potential economic partner. At some other times, Russia was treated as an adversary by nature. There have been many fluctuations depending on how different American presidents have dealt with the Kremlin. Europe has tried to approach the issue bilaterally. But when it comes to the European Union, it has never had a consistent way of dealing with Russia by being absolutely clear about what is different and what can be common.

What you said is fascinating because when I explain to my students that we live in an era of geopolitical recession, what I usually say is that there are three main reasons for getting into this situation: first, that Russia was not let into the new order after the collapse of the Soviet Union; second, that China was let in; and third, that globalization was not reasonably and rationally constrained, and it started backfiring, especially in rich democracies. I think it’s not completely unrelated.

It’s also kind of schizophrenic, if I may say so, because Russia has been targeted on several occasions because of its breaches of human rights, the neglect, undermining, or total squeezing of the values and principles of our world. Yet when it comes to the exact same issues, I don’t think China was much further ahead of Russia.

One can also talk about places in the Middle East, where things are not much better.

They are probably even further behind. This, to put it euphemistically, was not perceived well in Russia. There is also one thing that has been—at least from my humble knowledge of the topic—a continuum in Russia’s history: they have always looked West. Russian czars, and whoever was leading that part of the world, have always tried to look West to learn from it, bring in everything from technologies and goods to customs—even the customs of the royal house. So, Russia is Europe.

History has again demonstrated one thing: if there was a country in the world on which sanctions would never work, it’s Russia. They don’t need much to stand for thousands of years: they need boiled potatoes, vodka, and an enemy. If you give them these three things, you can’t get rid of them. If you take the enemy out of the equation and leave them with vodka and boiled potatoes, you have a chance of seeing them look for more democracy. Otherwise, an enemy is enough for them to rally around the flag and around whoever is in the Kremlin. How come we haven’t learned this? History has shown that, with Russians, you can always find a solution if you are able to leave them a way out. On top of that, they are a nuclear power. How come that, with such a nuclear power in a much more closed and tense world—when they faced off against the United States and the West with the Iron Curtain in the middle—long talks and efforts were made to reduce weapons of mass destruction, and we were able to move towards a more peaceful world? And now, we are sleepwalking in a new world where we keep on building tension.

Let me ask you something very hypothetical. You must have heard Mr. Putin say in one of his interviews that, back in the day, he spoke with Clinton and asked him if it would be acceptable to the United States if Russia joined NATO. Essentially, the American answer was no. I know it’s highly hypothetical under the current circumstances while blood is being spilled, but do you envision in the future—if rationale prevails, we calm down, and stop sleepwalking towards the conflict, as you put it—a new security architecture of greater Europe, similar to the one created by the OSCE in the late 1970s, which would include Russia and wouldn’t see it as an enemy on the other side of the divide?

For me, the question is not whether this will happen one day, but only at what cost it will happen. Again, it’s not just Russia. You are a professor today, but you come from quite an intense life of politics, and you are among the few people from our region who know the United Nations from within. Look at today’s frustration of the emerging powers that keep saying that we need a different Security Council. I’m talking about countries that are not looking for more unilateralism but more multilateralism. So even the UN needs to wake up and realize that it needs to re-engage the world differently, let alone when it comes to the existential need of all countries to guarantee a security architecture of the world. This outcome will materialize not just because of Russia but because of many other new realities. That’s for sure. The question is: at what cost? Until three years ago, we could not imagine that we would live in a world where words like nuclear threats and tweets about Oreshnik would be like talking in a bar. It’s crazy. And what it needs to explode is just one additional step. It takes just one crazy move, one crazy person, and it doesn’t seem like there is a shortage of them.

We can wish as much as we want that climate change is not as much of a threat as it really is. Meanwhile, we are seeing it advancing every summer, and now we have artificial intelligence adding to this. So, these are very big global challenges, threats, and avenues for the future that can either end in an apocalypse or in a better life for everyone. Our level of fight against them, our thinking, and our engagement is still so fragmented and back-to-back, as opposed to face-to-face, that it’s really mesmerizing.

It is mesmerizing, especially in Europe. I’m going to ask you one more question about China and Europe before I switch to the region where we come from. This one has to do with Chinese technology, and in particular electric vehicles, lithium batteries, and a new generation of vehicles. If you were in a room with your colleague, German Chancellor Friedrich Merz, and a bunch of executives in the German automobile industry, and the topic was what should be done with China’s vehicles—no other topic but “what on earth are we going to do, these guys seem to be better and cheaper when it comes to electric vehicles”—what would your advice to them be?

I have to say that I tried to set the tone in the beginning when I said that I can talk because I have my opinions. Still, I never forget that I am the Prime Minister of a small country. The best part of being the Prime Minister of Albania among the big guys is that you are one of them. You are sitting at the table equally with them. You can say whatever you think, but you are not cursed to make their decisions. So, you also have a very easy way out because if the decisions at those tables are good, you have participated in making a good decision, but if they are bad, you can say, “It wasn’t me, what could I have done?” So, it’s not for me to find out what Germany should decide about its industry.

There is one thing again in my very free flow of opinions—the reality of the climate change threat, which I humbly believe cannot be tackled even with electric cars. At the end of the day, there are only two things that cool our planet: trees and water. The rest play their own part in warming it and can also play a part in making it less warm. But when you see the level of deforestation in parallel with all the disorderly efforts of countries to fight climate change, the battle is lost. Chinese electric cars cannot save the planet. I heard the report that UN Secretary-General António Guterres made during the last COP (COP29), with one line saying that we have more negatives to deal with today than we did during the previous COP. The question is how can we mobilize humanity against deforestation and for forestation, as well as how we can make trees become as valuable as other goods under the circumstances of shortage. How come that while all other goods become more expensive during a crisis, a war, or a shortage, trees, although increasingly facing shortages, are the only commodity whose price doesn’t change? How can we encourage humanity to plant more, cut less, and protect more trees? This can happen only if we succeed in creating a system where trees have a real value. And this is another discussion for people who know more than me on this topic. What I always remember in these times as a reader of holy books is a phrase that, to me, had a different sense before and now again has a new meaning and looks more like a prophecy. In the Quran, when the Prophet says, “Even if the end of the world is upon you and you have one thing left to do, plant a tree.” It looks to me like a prophecy, a call in this time of ours to plant a tree, to plant it before the end of the world.

So obviously markets are not enough to regulate this; there will have to be a policy?

Maybe there is a way to think about creating a new market of digital currency connected to trees as an asset.

That is a very interesting idea. Maybe this is an idea that can emanate from the Balkans in order to enrich European and global discourse.

In the Balkans, we have conducted enough experiments trying to be a role model for changing the world. So, we’d better just change ourselves as much as we can, which is the most difficult thing—instead of trying to change the world.

I’m going to ask you about your regional cooperation and priorities for Albania. When it comes to security, you have exceptionally close relations with certain countries in the region. But then, when it comes to economic cooperation, there seems to be a different logic. The Open Balkan has been one of those “minilateral” initiatives in which Albania, North Macedonia, and Serbia have worked closely together to create a common labor market, simplify certain cross-border procedures, collaborate on education, and so on and so forth. You were one of the founders of the Open Balkan initiative, yet a couple of years ago you said that it had fulfilled its mandate and that the region should turn to different cooperation mechanisms—the Berlin Process, etc. At this stage in 2025, with everything happening in Europe that you and I have been talking about, what is your view of the Open Balkan and the future of this initiative?

First of all, the Open Balkan was created out of frustration with certain obstacles. The whole process of increasing economic cooperation, bringing down tariff barriers, increasing trade, and reducing obstacles to the movement of goods, people, and services was blocked the entire time by the principle of consensus. It was enough for one country not to be okay with any particular issue under the Central European Free Trade Agreement, and nothing would get done. The idea to create a locomotive was older, in fact, than when it materialized with the Open Balkan initiative and was something that I had been discussing with the president of Serbia. But from his side, there was always an impediment that had to do with the movement of people. When he opposed the movement of people, he had in mind the movement across the border between Albania and Kosovo, since it increasingly looked like there was de facto no more border between the two, while the movement between Kosovo and Serbia could not have been made completely free as in the former case. I always told him that this cannot be cherry-picking. The idea was that we do it fully, we set the example with very clear lines, allowing everyone who wanted to join to do so, while obligating nobody to take on everything. Those that wanted to do everything could do everything, with the same principle applying to those wanting to do only some of the things. Quite importantly, nobody could block others. Nobody could simply say no and block everyone, and those that would decide to behave this way would just end up blocking themselves. This is how the Open Balkan was created. Once we advanced in the EU integration process and were very clearly on the path to starting the negotiations, I thought that it would be great to bring the whole experience of the Open Balkan and throw it on the table for everyone to see. Because at the end, this is what countries will have to do. I think that the Open Balkan also served to include in this new growth plan the conditionality for obtaining support by demonstrating good behavior with the neighbors.

And do you believe, Mr. Prime Minister, that Albania is going to join the European Union as a full-fledged member?

I do. At this moment, I do, because there is a completely different way in which the EU approaches and looks at the prospect of enlargement to the Western Balkans. They’ve always said that the future of the Western Balkans was in the EU, but they were very slow, practically always leaving it for the future without doing anything at that particular moment. However, ever since the aggression in Ukraine, this issue has become much more momentous.

A new government of Germany was just recently formed, and the coalition agreement of the ruling parties said that there could be no new members in the European Union before the institutional reform of the bloc is carried out, so that there can be no more national vetoes for small countries. And although a small country can be led by somebody who, like you, says very explicitly, I know my place and where to engage and where not to, essentially, if you were to admit new members under the current institutional structure of the EU, you’d be giving Albania, Serbia, and everybody else a national veto in the decision-making of EU politics. Do you think this is viable?

First of all, I think that the part of the coalition agreement you are referring to is not exactly conditioning new members on fully reforming the EU. But on the other hand, I believe that there is a strong will to get new members. Especially at this moment, Montenegro and Albania look close to achieving this goal, with the assumption that we do all that is needed and that Europe does not have another slip. But as things stand today, I believe that this is possible.

OK, I’m taking bets as a professor with optimists with regard to the membership of the Western Balkans. Here, I would take the opposite bet, so we’ll see what happens in the future.

We are both men of the world, but in the end, you are the Serb and I’m the Albanian here. So, you are by definition the pessimistic one in this duo. It would be a complete surprise if you didn’t take the negative side of the bet.

I’m a professor, but I’m still a Serb. I have to ask you a question related to the change of borders. You know Serbia’s position when it comes to its borders, its constitution, and its description of Kosovo as an integral part of Serbia. If there is an explicit demand—a legally binding demand—as part of your accession process (assuming you’re right and that you are about to enter the European Union) and there’s this additional requirement that there has to be an agreement committing Albania not to join the adjacent territories in the region where there is an Albanian majority population. Would that be an acceptable condition for EU accession?

Meaning that Albania would pledge…?

Not to change its current borders in order to join the European Union.

Absolutely. Whether we do or don’t join, it is not an option for us to change borders. It is somehow a very unique reality to have two basically Albanian states, in the sense that Kosovo has a very large majority of Albanians, although it is multi-ethnic in its constitution. So, this makes the temptation very strong. But on the other hand, we live in the twenty-first century and we want to be part of the European Union. I believe that once every one of us is in the European Union, the borders will not matter. Being from this region, the more states, governments, MPs, and directors of agencies we have, the better it will be. If we all become one, then we would be tempted to split and resort to secession. I’m joking, but every joke has some truth in it.

There is one last question that I have for you in this interview. You know all European leaders; you hosted all of them just recently here in Tirana. Who is, in your opinion today, the strongest and most effective European leader?

This is a very difficult question. One of the most fascinating leaders, who is very smart, kind of like a tailor, capable of making coalitions, looking at the broader picture, and surviving every kind of debate and conflict with a big smile is Mark Rutte. I have great respect for him. I learned a lot from him because we had fights due to the very heavy stance of the Netherlands vis-à-vis Albania during our long integration process, when the Netherlands was vetoing us more than once while the European Commission was proposing to start negotiations. The Netherlands was the one that kept saying no, together with France, for instance. But the Netherlands was the tough dog. We had heated debates with Rutte, and the last thing he did with NATO was again very impressive. So, because of the circumstances, I got to know him a bit from a different angle, and I appreciate him a lot.