Sir Martin Sorrell is Founder and CEO of WPP plc, the world’s largest advertising and marketing services group.

Sir Martin Sorrell is Founder and CEO of WPP plc, the world’s largest advertising and marketing services group.

In today’s globalized world, it is often multinational companies, not national governments, that determine whether or not sustainable development is the path taken by a developing (what we at WPP call “fast-growth”) economy.

Of course, many other institutions influence decisions and track accountability, but this is an interplay profoundly weighed upon by the scale on which global companies operate and invest within developing nations in need of jobs and capital—both financial and human.

Unsurprisingly, and rightly, the size and impact of their operations and investments in such markets mean that multinationals find themselves under particular and often intense scrutiny.

Among the many pressures bearing upon global corporations as they handle the imperatives of sustainable development is a distinct split in consumer attitudes. In short, consumers in less developed countries place greater importance on sustainability in their personal lives than do consumers in more developed countries.

Demand Duality

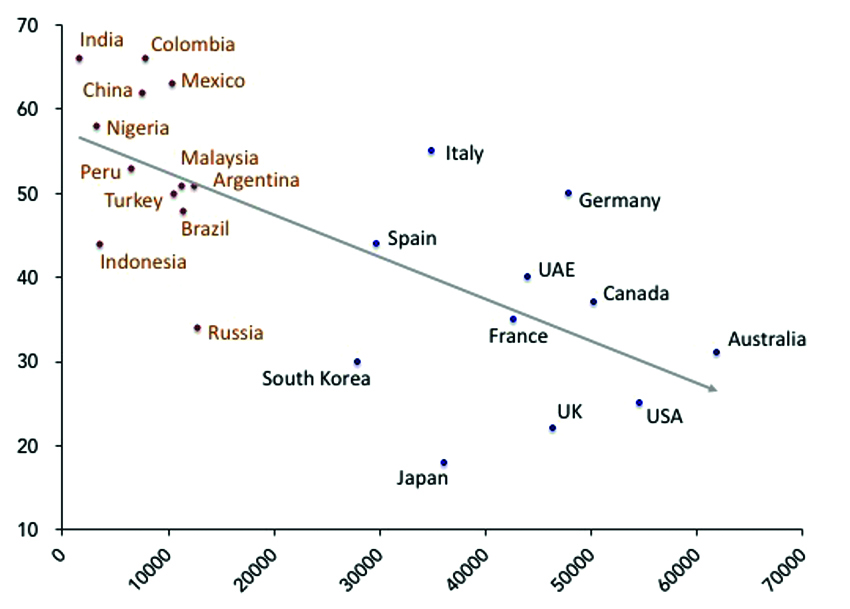

Data from Global MONITOR—the strategic insights resource from WPP subsidiary The Futures Company—makes this “duality of demand” very clear. Researchers asked consumers to what extent they agreed with the statement: “I have made it a top priority to live a more environmentally conscious lifestyle.”

As shown in Chart 1, there is a strong correlation between GDP per capita (as reported by the World Bank) and the levels of agreement. The broad pattern is that, in lower GDP per capita countries, the percentage of people agreeing with the statement is significantly higher whereas in higher GDP per capita countries it is significantly lower.

Chart 1 / % Top 3 Box agree: “I have made it a top priority to live a more environmentally conscious lifestyle” (2015 Global MONITOR 10-point anchored scale vs. “I never worry about green and environmental issues. I have other priorities”) / 2014 GDP Per Capita – The World Bank http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD / Illustration: The Futures Company

There are, of course, nuances and pockets of shared opinion everywhere. Russia is an outlier among the so-called developing nations, with relatively low levels of agreement, while India and Colombia top the ranking for the most (self-declared) environmentally conscious citizens. At the other end of the scale, in the cluster of developed nations, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States show the lowest levels of agreement, with Italy, Germany, and Spain at the top.

However, in general terms, agreement is pretty strong in developing countries and pretty weak in developed countries. This is a major difference of aggregate popular opinion—a genuine duality of overall sentiment.

This presents a challenge to multinational companies that are trying to create as much scale as possible across all segments of their businesses. All multinationals recognize that brands must fit local preferences, culture, texture, and styles. These days, no one tries to force an identical brand on every market. That was the model half a century ago, but not today.

Competing Market Situations

The challenge is that while brands need to be customized by market, corporate reputations carry across national boundaries. What you do in one market affects how you are perceived in every market. The free flow of information ensures this. The heightened scrutiny of social media facilitates this. The diminished trust in business (and other institutions) everywhere exacerbates this—not to mention the ever-more-vocal pushback from nativist and nationalistic groups.

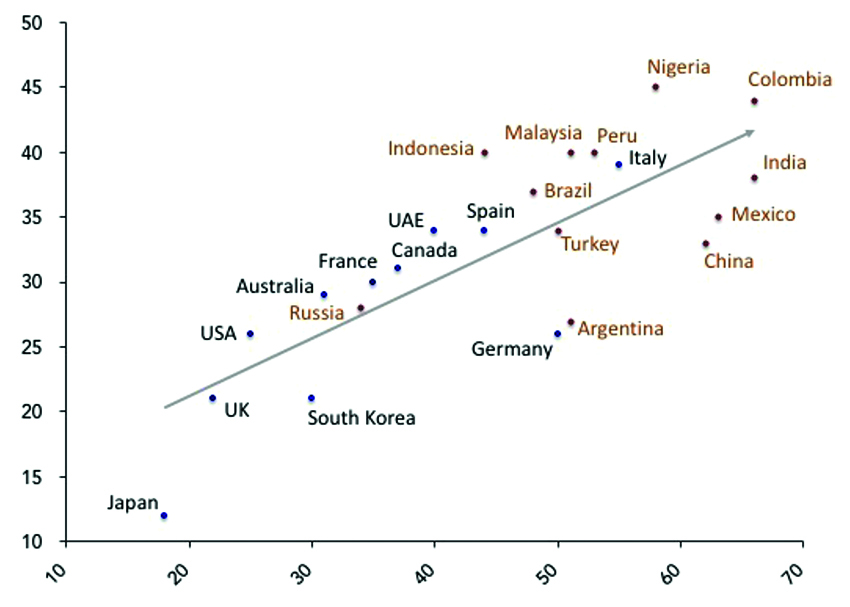

Chart 2 / % In last few years, have bought from companies with clear, committed environmental policies (2015 Global Monitor vs. “did not”) / % Top 3 Box agree: “I have made it a top priority to live a more environmentally conscious lifestyle” (2015 Global MONITOR 10-point anchored scale vs. “I never worry about green and environmental issues; I have other priorities”) Illustration: The Futures Company

The duality of demand creates competing market situations for companies. You see this in Chart 2, which plots responses to the first statement (“I have made it a top priority to live a more environmentally conscious lifestyle”) against responses to a second statement (“In the last few years I have [deliberately] bought from companies with clear, committed environmental policies”).

Again, there is a very strong positive correlation. For countries with a large percentage saying sustainability is a top lifestyle priority, a large percentage of respondents also say they try to buy from companies committed to sustainability. And vice versa. This is the translation (albeit self-reported) of sentiment into intentions or actions, and explains why this duality matters to multinational companies trying to figure out how to manage across markets in a world where everything they do is known everywhere at once.

The point is that sentiment carries over into decisions, so multinational companies must figure out how to do business in the face of this contradiction.

On a simplistic level it’s pretty straightforward. I don’t know any CEOs who see sustainability as anything other than a central, business-critical issue. The days of greenwashing and paying lip-service to corporate responsibility are over. Doing good is just good business, if you are building brands for the longterm. However, while adapting to local preferences in product design, retail, and service is well within the wheelhouse of these companies, making investments in sustainable development is a lot more complex.

Going “All In”

It will, inevitably, carry an organization in a particular direction. Resources and time must be prioritized, and sustainable development is not an insignificant commitment. It’s often a case of “all or nothing,” when you have to go “all in.” A multinational company may have to make a decision about whether to go all in against the backdrop of a global marketplace that is not all in. While the world may be of two minds, split along an economic divide, the multinational company will nonetheless need to make a single-minded commitment to sustainable development.

This is a risk, and the current corporate climate does not encourage risk-taking. Companies face a world of low GDP growth, little or no inflation, and little or no pricing power as a result. At the same time they are being squeezed from every direction: by disruptors like AirBnB and Uber; zero-based budgeters like 3G, Valeant, and Endo; and activist investors like Nelson Peltz, Bill Ackman, and Dan Loeb. As a result, boards are understandably conservative in their decisionmaking and focused on cost management.

Going all in is also much more difficult for long-established “legacy” businesses with structures, practices, and cultures that may stretch back decades. As with traditional media businesses trying to reinvent themselves for the digital era, it’s like changing the engines on the plane while it’s still flying.

So taking this leap—to go “all in” on sustainability—requires vision, leadership, and more than a little courage.

An award-winning white paper by The Futures Company’s Andrew Curry and sustainable development expert Jules Peck entitled “The Twenty-First-Century Business” sets out a path for multinationals to take, and it involves thinking about their businesses in a different way.

One of the authors’ central arguments is that past business models and best practices encouraged companies to build organizations and market infrastructure that were “closed” and “fixed,” predicated on the need to maintain tight control and strictly manage efficiencies. But, they say, such business models are being overwhelmed by the emergence of a more open, fluid world.

Contradictory or inconsistent market conditions (like demand duality in sustainability) are harder for closed, fixed models to accommodate. The way for multinational companies to approach sustainable development is not, therefore, as simply the planning priority of the moment, but as an opportunity to face up to the bigger imperatives of doing business in the twenty-first century and, perhaps, to change the nature of the business itself.

Many companies are already doing this. As Curry and Peck say: across the business world there are examples of companies that have started to absorb the lessons of the twenty-first century and have started to adapt. They are innovating their business models, their corporate systems, and their organizational hierarchies.

They cite Unilever as one such company that has made sustainable development integral to how it does business. Led by CEO Paul Polman, Unilever has without question gone “all in,” as encapsulated by this unequivocal statement on its website: with seven billion people on our planet, the earth’s resources can be strained. This means sustainable growth is the only acceptable model of growth for our business. The Unilever Sustainable Living Plan sets out to decouple our growth from our environmental impact, while at the same time increasing our positive social impact.

Moral Compass

Polman has taken a personal stand on the issue, engaging with initiatives such as the Inclusive Capitalism Taskforce, the Sustainable Economy Project, The B Team, and the “We Mean Business” Coalition.

Many enlightened companies have concluded that the requirements of sustainable business are not in opposition to their commercial interests, but in tune with them. The personal vision and commitment of corporate leaders like Unilever’s Polman leads to the same destination as the logic of being in business for the longterm (regardless of demand duality). As Polman puts it, sustainable business is “where our moral compass meets the bottom line.”

By 2030, a predicted 4.9 billion-strong global middle class will drive increasing demand for consumer goods and services. But to meet the needs of this huge market, brands will have to overcome significant social and environmental challenges. The impact of climate change, ecosystem decline, and water scarcity will limit supplies of natural resources, increase material and manufacturing costs, and disrupt supply chains.

There will also be unprecedented strains on food resources, infrastructure, and public services. Access to employment and the need for equality of opportunity will continue to be major concerns as well. Society will look to business to play a major role in addressing these challenges, while technology will continue to transform the way consumers and citizens engage with brands, all while keeping the spotlight on business practices and values.

To succeed in this new environment, brands will have to make fundamental changes to business models, supply chains, products and services, and the way they engage with customers and stakeholders. They will look to marketing services businesses like those within WPP for the strategic insight, research, and communications guidance they need to make this change happen.

Today’s leading businesses have already started on this journey, and our companies are working with many of these pioneers. As these longer-term trends become more important for our clients, their significance will grow for WPP too. Increasingly, we will need to demonstrate to our clients that we have the insights and knowledge they need to succeed in this new era for business, and that within our own businesses we also apply high standards and values to the way we operate. The work our companies are doing today will lay the groundwork for success in the business environment of the future.

To give a sense of scale, clients who engaged with WPP on sustainability were worth at least £1.35 billion to the Group in 2014—equivalent to 12 percent of revenues, a 7 percent increase on the previous year. This will only increase further.

Those businesses fundamentally reexamining how they operate see their transformation not as a necessary evil, but as an opportunity to improve their market position. Curry and Peck describe this more open, flexible “business of the future” as one that is “more outward-facing, seeing a change of external environment as a source of potential rather than risk.” In other words, an “all in” commitment to sustainable growth is a point of highly positive competitive differentiation.

Adam Morgan, who popularized the expression “challenger brand” in his book Eating the Big Fish: How Challenger Brands Can Compete Against Brand Leaders (1999), frames the question as follows: “How do you make a constraint beautiful? How do you make it something that leads to an outcome that is better than you had before?”

Curry and Peck highlight UK challenger bank TSB as a company that is doing just that by positioning its brand as a response to tighter regulation of the banking sector in the wake of the economic crisis. “TSB communicates that it is building a business that doesn’t need to read 600 pages of regulations to know if it is doing the right thing. It has turned risk into opportunity.”

Open Innovation

There are numerous examples of businesses taking a more open, “outward-facing” approach to innovation, including the 13 multinationals that have pooled 100 eco-patents under the World Business Council for Sustainable Development’s “Eco-Patent Commons” scheme. The principle is simple: “anyone who wants to bring environmental benefits to market can use these patents to protect the environment and enable collaboration between businesses that foster new innovations.”

Sir Martin Sorrell / Photo: Guliver Image/Getty Images

There was a time when such a strategy—effectively mutualizing IP—would have been unthinkable: reckless, risky, and contrary to the interests of the company and its stakeholders. Many companies probably still feel that way about it, but according to some they are paddling against the tide.

Mike Barry, Director of Sustainable Business at Marks & Spencer, says: it’s all about being open now. You need to open up your business, build partnerships and shift your mindset to develop an outside-in way of working. Letting the outside in to shape not just your thinking but your actions too. Moving away decisively from the twentieth century view of ‘them and us’ and lecturing others from the ‘inside.’

Joel Makower, the author and entrepreneur, highlights the role of open innovation in sustainable development in his 2015 State of Green Business report. As he says: Open innovation took off initially in the software world, where systems such as Linux and Apache were built by thousands of individuals, all of who ceded ownership of the basic code, but were able to use the collective creation to launch their own products and services. Today, that mindset is imbuing the sustainability marketplace with everything from electric cars to agriculture to water systems. And it is being employed by some of the world’s biggest companies—among them, GE, GM, Siemens and Unilever—to create the next generations of low-carbon technologies.

Makower points to the ever-growing list of mainstream companies that are opening up their processes, IP, and mindset in order to drive sustainable growth. Quoting him further: A wide range of companies in sustainability-related industries as varied as minerals and mining, energy systems, electric vehicle charging, and water management are turning to open innovation platforms for new sources of innovation and inspiration. Philips International B.V., the Dutch electronics giant, created the simply innovate platform to drive new levels of innovation and efficiency in lighting products. Unilever launched an online platform offering experts the opportunity to help the company find the technical solutions it needs to achieve its ambition of doubling the size of its business while reducing its environmental impact. ABB, the Swiss-based global power and automation technologies company, is launching open innovation partnerships with universities, research institutions and others to develop an open smart grid ecosystem. Last year, GE launched an open innovation challenge aimed at improving the energy efficiency, decreasing emissions and reducing overall the environmental footprint of mining tar sands oil.

Companies prioritizing sustainable growth—whether through open innovation or other means—have grasped the fundamental truth that sustainability is not the enemy of their business, but the key to its longterm health.

Brands that intend to be in business for the longterm need to think more strategically about their role in society and their purpose as a business. They need to consider how they can operate sustainably in a changing world while generating value for shareholders, customers, employees, and wider society.

Businesses with a purpose beyond profit can command greater customer and employee loyalty, along with greater resilience in this changing environment. Successful businesses will see their customers as more than just consumers. By integrating sustainability into their business and thinking, they can create products and services that address customers’ real and changing needs whilst making a difference in their everyday lives.

IKEA, for example, is investing €1 billion to support climate action, made up of a €600 million investment in renewable energy generation (equivalent to 100 percent of the energy it consumes) and €400 million to back communities most impacted by climate change. It has switched its whole customer lighting range to energy efficient LED.

The Circular Economy

There are also major opportunities from new markets for more sustainable products and services, especially in areas such as smart technology, alternative energy, and the sharing economy. McKinsey estimates that the circular economy (the continual reuse and recycling of resources and the replacement of physical product sales with alternative services) could add $1 trillion to the global economy by 2025.

Caterpillar is one of many companies investing in circular economy business models. Its remanufacturing business takes back over 80,000 tons of end-of-life material from customers annually and remanufactures it into good-as-new condition. In total, its circular economy portfolio generated almost $10 billion in 2014—representing 18 percent of total revenues.

Already citizens expect, and increasingly demand, that businesses play an active and positive role in tackling global challenges alongside governments.

I began this essay by highlighting the fact that, in developing countries, it is often businesses rather than governments that will have the greatest impact on those countries’ approach to sustainable development. But in mature markets, too, companies will, by necessity, have a major role to play. So I’d like to end with a plea to political leaders and policy-makers not to forget that commerce, as an inherent component of our global system, is inevitably a vital part of the sustainable development solution.

It is everyone’s interest that the recently adopted Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—the UN’s ambitious targets “to end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure prosperity for all”—are a success. At the end of September 2015, the heads of more than 20 of the world’s leading businesses (including Alibaba, Facebook, Dow Chemicals, Virgin Group, and WPP) signed an open letter calling on political leaders to work with the private sector to help deliver the SDGs.

To quote from the letter:

The international development agenda is sometimes narrowly construed as a matter for governments alone, but it is clear that effective implementation of the SDGs will require widespread business support. To take one angle: official estimates place the annual investment gap in sustainable development in developing markets at up to $2.5 trillion annually. It is anticipated that much of this shortfall will need to be filled by private capital. In other areas, business expertise and innovation will be key if we are to limit greenhouse gas emissions, create new jobs and promote sustainable consumption cycles.

It signed off with this message:

Many businesses are already playing a leading role in promoting sustainable development, but with the right support and incentives from government we can do much more. A collaborative effort is also required to enable the transformation of business practices towards sustainability more broadly—including within the small business sector. While the SDGs address many complex issues, our message is simple: let us work together to seize this once in a generation opportunity to deliver a brighter and more prosperous future for all.

Simply put, governments alone do not have the resources to tackle the towering problems that the SDGs seek to address. There are only so many levers they can pull. By working actively and constructively with business, policymakers will find that many more levers become available to them, and a great deal more can be achieved.