Rüdiger Frank is Professor and Head of Department of East Asian Studies at the University of Vienna. You may follow him on Twitter @GTDRP.

Rüdiger Frank is Professor and Head of Department of East Asian Studies at the University of Vienna. You may follow him on Twitter @GTDRP.

Roughly two decades ago, very few people outside of Korea were following developments in and around the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), more commonly known as North Korea. To them, what happened in the first half of 2018 must appear extraordinary and unique. From “fire and fury,” “dotard,” and dangerous bragging about “nuclear buttons,” events turned to no less than six summit meetings of North Korea’s hitherto isolated leader, Kim Jong-un, the dismantlement of a test site, the release of American detainees, and a bunch of smiles and handshakes.

This article aims to place events like the April 2018 inter-Korean summit and the first ever North Korean-American summit in June 2018 into context. It is this author’s hope that this essay can help to provide a more sober and objective evaluation of what has been achieved this year, and render more realistic expectations of what could follow.

Back to the Future

Many seasoned observers argue that we “have been there” before. This is true; but we must note that a long time has passed since there was a similarly encouraging and positive era in North Korea’s international relations.

We need to go back as far as the beginning of the twenty-first century, but the world was different back then. Russia was still trying to recover from the shock of the Soviet Union’s collapse, China was in earlier stages of its rise, smartphones did not exist, and the United States was the only global superpower. The “War on Terror” had not even begun, a refugee crisis was not in sight, and men like Saddam Hussein and Muammar Gaddafi were safely in power.

In June 2000, the two Korean leaders of that time—Kim Jong-il of North Korea and Kim Dae-jung of South Korea—held the first inter-Korean summit in history. Kim Dae-jung traveled to Pyongyang, and Kim Jong-il scored a major public relations victory simply by behaving like a normal person. He smiled in front of cameras, raised his glass for toasts, and showed his guest the appropriate respect, as it is right and proper to do towards an elder according to Confucian ethics.

South Koreans were taken aghast, in particular since they had for years been told by their own propaganda machine that the North Korean leader was a deeply shy and insecure person who could not even speak Korean properly because of an injury from a car accident. This negative image, which had been built for many years, evaporated in a matter of hours and made room for a boundless and unrealistically high level of optimism with regard to the immanence of Korean unification.

Looking at the summits of 2018, this sounds strikingly familiar.

In 2000, the two Kims signed a Joint Declaration, and substantial actions followed. The inter-Korean tourism project,

inaugurated just over a year before, was substantially upgraded and, until its cancellation in 2008, had brought about two million South Koreans to North Korea. They visited the mountain resort of Mt. Kŭmgang, the old Buddhist capital of Kaesŏng and even the Arirang Mass Games in Pyongyang.

The decision to establish the joint Kaesŏng Industrial Zone immediately at the border with South Korea was implemented in 2004. Before its closure in 2016 by the South Korean side, 50,000 young and female North Korean workers were employed by over 120 South Korean small and medium-sized companies, along with about 1,000 South Koreans. They produced mostly light industry goods, such as watches, shoes, or rubber seals, for the South Korean market. This was the single-most important example of regular, day-to-day contacts between the two Koreas since the end of the Korean War. From the perspective of 2018, it is important to be aware of two things: first, that such progress had already been made; and second, that it was later undone.

In late 2000, Kim Dae-jung was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts. His North Korean counterpart was left empty handed, as if to demonstrate that the inter-Korean summit had to be seen as a South Korean victory over its evil foe from the North. But that did not discourage Kim Jong-il from unleashing a whole wave of changes that only the North Koreans themselves refuse to call reforms. After a rare programmatic article extensively quoting Kim Jong-il in the Party newspaper calling for “appropriate adjustment in response to the changing environment” in January 2001, massive action was taken in July 2002.

For instance, the price and incentive system was adjusted to the new economic realities that had emerged as a result of the famine of the mid-1990s. In many ways, the North Korea we see today—much more modern, diversified, and better informed—is a product of those years of reform. It is encouraging to see that some of the positive effects have survived the subsequent breakdown of North Korea’s international relations.

Moreover, active steps were taken by Pyongyang towards reconciliation and normalization with Japan. In September 2002, the Japanese Prime Minister held the first ever summit meeting with a North Korean leader. Koizumi and Kim discussed the main concern of the Japanese side, namely the abductee issue, which refers to more than a dozen Japanese nationals who were kidnapped by North Korean agents in the 1970s.

The North Korean side, usually known for strictly denying all accusations, surprisingly admitted to some of the charges and, in another very rare case, apologized. Moreover, a handful of survivors were allowed to board the Japanese Prime Minister’s plane and return home with him. This short episode shows that there is a striking North Korean ability to make hitherto unimaginable concessions if the regime thinks the time is right and the effort worthwhile.

But the main reason why it is useful to start a discussion around the events of 2018 and their possible implications and consequences with a view to the past is to be found in what followed after this flurry of encouraging signs. Much of the hard-won progress was undone, and we are well advised to understand how and why this could happen, so as to have a more effective and lasting approach this time.

The End of Engagement

Between the June 2000 summit and the July 2002 reforms, the world changed dramatically. The 9/11 attacks gave the ailing George W. Bush Administration a new and powerful raison d’être. The “War on Terror” was waged against an unconventional enemy, but it needed conventional targets. In his January 2002 State of the Union address, Bush identified an “Axis of Evil” of only three countries that included North Korea (the other two were Iraq and Iran). In May 2002, Undersecretary of State John Bolton—who became National Security Advisor to President Donald Trump in April 2018—added three more countries, including Libya and Syria, to that list. Their fate is known.

In Korea, what had looked so promising began to crumble. Despite North Korea’s half-hearted apology, the normalization with Japan did not happen due to a negative reaction by the Japanese public and, as rumor has it, intervention by a major ally. After a visit by an American envoy in October 2002, North Korea was accused of having violated its commitments to the nuclear deal struck in 1994. Pyongyang reacted angrily and in January 2003 withdrew from the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty. After the American-led invasion in Iraq in March 2003, North Korean reforms visibly stalled.

In November 2002, the European Union joined the United States in demanding what became the catchphrase of the following decade: complete, verifiable, and irreversible dismantlement of the nuclear program, also known as CVID. The EU and many of its member states had re-established diplomatic relations with Pyongyang as of 2001, and exchange programs had just begun to take root. All this was halted and over the following years reduced to little more than a distant memory of what had once seemed possible.

Meanwhile, North Korea announced its Military First Policy and declared that the possession of a nuclear deterrent was the only guarantee of Korean independence. Resources were directed primarily towards the military. In 2006, the country conducted its first nuclear test. Further tests followed in 2009, 2013, 2016, and 2017. They were accompanied by efforts to develop multi-stage rockets for a space program, interpreted and criticized by the West as a ballistic missile program. Nuclear and missile tests took turns and led to the imposing of a growing number and intensity of sanctions. Eventually, even China could not avoid joining these Washington-led efforts.

Succession

In late 2011, Kim Jong-il died. He had not named a successor, but his youngest son, Kim Jong-un, had been introduced to the public just a year before at the first Party Conference in more than four decades and was now quickly announced as the “great successor.” Many observers wondered whether he would be able to keep his country afloat, or whether the collapse of North Korea—predicted so many times before—would now finally happen.

Perhaps it was this hope that prevented the United States from undertaking a bolder attempt to reach out to the new leader, who at that point had not yet taken personal responsibility for the North Korean nuclear weapons program or the humanitarian and human rights situation in his country. But that golden opportunity passed unused. The Leap Day Agreement of February 2012 did not survive more than a few weeks, due—accidentally or deliberately—to contrasting interpretations of its meaning.

When Donald Trump was elected President of the United States, the situation with North Korea escalated quickly. Hopes did not materialize that the man known for his unconventional approach his disregard for established rules and procedures would ignore America’s previously drawn red lines, including CVID, and simply sit down with Kim Jong-un to find a way out of the impasse.

On the contrary, in 2017, the confrontation reached new heights. On May 1st, Trump declared that he would be “honored to meet Mr. Kim,” but North Korea decided to push the envelope further and on July 4th test-fired an Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM). Another one followed on July 28th. A new round of UN sanctions was met with angry North Korean threats. On August 8th, Trump threatened to unleash “fire and fury” against North Korea. Pyongyang responded swiftly on August 9th by threatening a nuclear strike against Guam. Trump announced that the United States was “locked and loaded” in the case that North Korea acted “unwisely.”

Then, on September 3rd, North Korea conducted its sixth nuclear test, with another missile launched by North Korea on September 15th. In his speech to the UN on September 17th, Trump called Kim Jong-un “Little Rocket Man” and vowed to “totally destroy” North Korea. Until November, Kim and Trump traded insults by calling each other a bunch of names, including “mentally deranged dotard,” an “old lunatic,” and “short and fat.” On November 29th, North Korea launched its most powerful ICBM to date. At the beginning of January 2018, Kim Jong-un and Donald Trump engaged in a war of words over the size and functionality of their alleged “nuclear buttons.”

A Sudden Change of Mind?

Against this background, hardly anybody expected that, only six months later, the two contenders would smile at each other and shake hands.

It is tempting to diagnose something like a mysterious sudden change of the mind of the North Korean leader. Such an assessment corresponds well with the mainstream image of North Korea as unpredictable, enigmatic, and erratic, but it is very unlikely to be correct.

The other often used argument that it was Trump’s “maximum pressure” policy that brought Kim to his senses is equally hard to defend, considering North Korea’s long-standing resilience against sanctions, the short duration of the new sanctions, and the lack of a visible domestic economic crisis on the ground.

Rather, North Korea seems to be following a long-term strategy that has been publicly announced and adjusted a number of times. Amidst the many threatening events of the year 2013, with a war-like atmosphere comparable to 2017, it was easy to overlook a major ideological turn: the announcement of a new policy line.

After declaring that his country was now a nuclear power and including a related addition to the preamble of the North Korean constitution, Kim Jong-un declared that his country would from now on pursue parallel development of nuclear weapons and the national economy. The new policy line was named pyŏngjin. Despite its bellicose appearance, pyŏngjin marked a departure from the Military First Policy (sŏngun) that had been introduced a decade prior. Rather than “all for the military,” the new motto elevated the economy to the same rank and thus effectively halved the role of the military.

The official logic behind this change was that now, as a nuclear power that was thus relatively safe from invasion, North Korea could afford to focus more on its economic development.

After the ICBM launch of November 2017, Kim Jong-un went a step further and declared the successful conclusion of the development of nuclear weapons. In a speech mostly ignored by Western media on April 20th, 2018, he declared that the pyŏngjin line had been implemented successfully and that it would now be replaced by a new strategic line to “concentrate all efforts of the whole party and country” on economic development.

Within just five years, North Korea went from “all for the military” to “all for the economy.” This corresponds with our 2012 analysis of Kim Jong-un’s approach, when right after becoming the new leader he emphasized economic development and the improvement of the living standard of his people as his top political priority.

One could go as far as to assume that Kim Jong-un wants to base his very claim to legitimacy on the success of this economic prioritization. Moreover, if he ever wants to achieve unification with South Korea that will not resemble a version of the German example—a takeover of a weak North Korea by a strong South—then he needs to do something about the huge gap in economic development and prosperity between the two Koreas.

“It’s the Economy, Stupid!”

So, all this might be just another case of the well-established paradigm in which economic concerns often have a determining impact on politics. The aforementioned focus on economic success is where we can get some clues about the long-term strategic orientation of Kim Jong-un, and in particular the origin of his allegedly “sudden” willingness to talk with South Korea and the United States. It is very likely that these encouraging events of 2018 are part of a script that was being played out for many years.

From a purely academic perspective, and as absurd as it may sound, North Korea does indeed have the potential to become the next East Asian tiger. Many of the well-documented success factors of what is often referred to as the “East Asian development model” are present.

Consider the following: North Korea is ruled by an autocratic regime that will be able to implement a strategic economic policy. It has a highly-educated population that is willing to make huge sacrifices in the hope of a better life for their offspring, much as could be observed in Japan or South Korea a few decades ago. North Korea is already an industrialized country; it needs massive modernization, but major changes like urbanization took place long ago. Ceremonialism in the form of a Confucian antipathy towards commerce and manual labor has long been overcome. In addition, North Korea has what other followers of the East Asian model of economic development could only dream of having: abundant natural resources and a direct land border with China, the region’s biggest market and source of investment. This time, China—and not the United States—could thus play the role of the major external partner providing support out of political and strategic considerations, another key component of the model.

But North Korea is infamously known for its inefficient economy and even food crises. This does not sound anything like a country that is ready to join the ranks of the most dynamic economies in the region. The answer to the question of why North Korea has so far not been able to realize its huge potential explains the recent efforts at rapprochement with the United States.

Central components of the East Asian development model include a strong export orientation, the import of technology, and a reliance on external finance. A crucial precondition is a close connection with, and access to, international markets for goods, services, and finance. But this is what North Korea, unlike the other Asian tigers, does not have. On the contrary; it is subject to massive and broad economic sanctions. It is impossible to make any financial transfer to North Korea, and the country is forbidden to even export textiles.

The North Korean leadership has studied closely the economic development stories of Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Vietnam and, most recently, China. It fully understands what it needs to do, but at the same time has no intention of following the destiny of the Soviet Union, where economic reform led to a collapse of the political system. The development of a nuclear deterrent is, from this perspective, a step to ensure that the inevitable economic opening-up will not result in a political takeover by hostile forces. The existence of South Korea is a major challenge in this regard, and makes North Korea’s position more delicate than that of most other transition economies.

Kim Jong-un’s Prerogatives

Kim Jong-un has explicitly and repeatedly prioritized the economy, especially in the wake of having secured a nuclear deterrent as a guarantor of security from external intervention. He knows he needs to get rid of the economic sanctions against his country, and knows that he will benefit from using the markets, know-how, and financial resources of South Korea, Japan, and China—and even that of the United States. This

explains his willingness to sit down and talk with the leaders of all these countries.

But a question remains regarding what he is ready to offer in return.

If the aforementioned analysis is correct, then CVID and any similar kind of denuclearization is a non-starter. The North Korean nuclear weapons program was not developed to sell at the highest possible price. It is supposed to form the very foundation of an economic development strategy that will elevate North Korea to the level of South Korea and thus prepare for an eventual Korean unification at eye level. All other things being equal, the possession of nuclear weapons might even tilt the balance of power in North Korea’s favor and allow it to eventually dominate a Korean unification process.

There is little disagreement amongst analysts that, against this background, it is very unlikely that Kim Jong-un is ready to give up his nuclear weapons. It is thus easy to conclude that the recent talks are nothing but a cynical game for time. But in case they are not, what can the North Koreans reasonably be expected to offer?

The North Koreans know that they will not, at least for now, be able to receive the official blessing of the West for their status as a nuclear-armed state. They therefore offer the “denuclearization of the Korean peninsula” as a remote goal for a very distant future, very much like the UN declaring that it wants to end human rights violations and poverty on a global scale. The purpose of the above-stated formulation is to lay out a vision, an ideal, and then start working on much less bombastic details and small steps in that very direction.

However, there are issues on which the North Koreans are indeed willing to compromise. This concerns limiting the number of their nuclear weapons. They are willing to stop testing nuclear warheads. Pyongyang might even be ready to stop launching ballistic missiles, although this will require some clarification on how the North Korean space program is interpreted by the West. In 2002, ideas were floated about allowing the North Koreans use European Ariadne rockets to carry their satellites into space; something similar could be discussed, this time perhaps with China replacing the Europeans as the main cooperation partner in this regard.

In addition to these various freezes, North Korea seems to be ready to accept verification and monitoring to a certain degree, for example through inspections by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Such inspections have taken place before, so there is a precedent. The United States should, however, be ready for tough negotiations about a quid pro quo—which could go as far as North Korean inspectors visiting American or South Korean nuclear facilities.

Given the current global terrorist threat, the whole topic of non-proliferation is another area with potential for negotiations. North Korea has repeatedly hinted at its commitment to be a “responsible nuclear power,” which implies a willingness to refrain from selling nuclear hardware or know-how. Needless to say, the return to the Treaty on the Non-proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) or a similar agreement will again come at a price, but at least there is a realistic possibility to achieve such a deal.

Especially after the tragic events in Fukushima, the issue of nuclear safety is another important field for a negotiated agreement with North Korea. Given the country’s reputation for bad maintenance of technical equipment, it seems only a matter of time until a major accident happens, polluting the Korean peninsula and its surroundings. Here, too, the IAEA could be an accepted and professional partner.

None of this—if it ever happens—will come for free. The list of North Korean demands is long, and likely to expand in the future. For now, the long-known goals of the North Korean side include a peace agreement to end the Korean War, most likely directly connected with a normalization of diplomatic relations with the United States. This will not only include the establishment of embassies in Pyongyang and Washington, but also demands for payment of reparations to cover the damage done during the Korean War.

As soon as these two stumbling blocks have been removed, North Korea would aim for a dismantling of the existing bilateral and international sanctions. The latter can be promoted by China, a permanent member of the UN Security Council, but would still need American acquiescence, for just like Beijing (and Moscow, Paris, and London) it can exercise its veto in the Council.

A look at this list of mutual expectations and demands reveals that we are at best looking at a long, protracted process with the near-certainty of facing serious setbacks—and with huge potential for failure. A one-shot solution in the form of one big, comprehensive agreement seems unrealistic, if not outright impossible. The most promising approach is thus a gradual, staged approach where trust is built through a tit-for-tat process.

This is why certain voices are getting louder in Washington, questioning the effectiveness of fly-by night management by the U.S. Secretary of State and calling for a special envoy tasked with dealing with the North Korean issue exclusively and intensely.

The Two Summits in Context

With the above in mind, it is possible to contextualize properly the events of 2018. There was no change of mind in Pyongyang. Strategically speaking, North Korea was ready for talks with Washington after it had

successfully developed a nuclear deterrent that could reach the United States. An attack against North Korea, or even a significant destabilization of the situation there, would now be perceived to be as much of a national security risk for the United States as the existence of the nuclear program itself.

Tactically, two factors have played a role. One of them is the personality of Donald Trump, the most unconventional President of the United States with whom the North Koreans have ever had to deal. His willingness to ignore conditions set by previous American administrations has provided a unique opportunity to break out of the deadlocked situation.

The second factor is the South Korean president, Moon Jae-in. He was elected after two consecutive conservative presidents (Lee Myung-bak and Park Geun-hye) and in the wake of Park,s inpeachment on corruption charges. Moon is known as one of the supporters of the Sunshine Policy of engagement that formed the cornerstone of the inter-Korean policies of the Kim Dae-jung and the Roh Moo-hyun administrations from 1998 to 2008.

There is no reliable evidence for a coordinated effort between the two Koreas, but they have acted very much in-sync during the 2018 events. On New Year’s Day 2018, Kim Jong-un gave his annual New Year speech and, as each year, included an appeal for peace and cooperation on the Korean peninsula. Moon Jae-in grasped this opportunity and on January 9th invited a North Korean delegation to participate in the Pyeongchang Winter

Olympics. North Korea accepted. The two Koreas formed a joint ice hockey team.

On February 9th, Kim Jong-un sent a delegation that included the nonagenarian Kim Jong-nam, who, in his capacity as President of the Presidium of the North Korean parliament, is also the nominal head of state, and—most crucially—his younger sister Kim Yo-jong. This was the highest-ranking North Korean delegation that had ever visited South Korea. Most importantly, Kim had sent a close blood relative, which matters everywhere—even more so in East Asia, and in the family dynasty of North Korea.

Kim Yo-jong became a central figure in the events around that visit. She attracted huge attention from the South Korean media with her humble but resolute attitude and her Mona Lisa-like smile. American Vice President Mike Pence lost many sympathizers in South Korea when he remained seated during the entry of the joint Korean delegation during the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games, and when he refused to even look in Kim Yo-jong’s direction, although the two were seated just a few steps away from each other. Rumor has it that this was preceded by a disagreement over the modalities of a meeting between Pence and Kim.

Later, Kim Yo-jong, in a grand gesture so typical for North Korean diplomacy, handed Moon Jae-in a personal letter from Kim Jong-un, carrying the invitation for an inter-Korean summit. Moon was careful enough not to accept the invitation immediately, knowing too well that a third such summit (the first two took place in 2000 and 2007, respective) for symbolic reasons could not take place in Pyongyang again, and that convincing Kim Jong-un to travel to Seoul would be difficult.

But the ice was broken, and, after an exchange of emissaries, the third inter-Korean summit was set to be held on April 27th in Panmunjom. The choice of location was Solomonic; technically speaking, Kim Jong-un did indeed travel to South Korea, but on the other hand the area bears many characteristics of neutral ground.

The Inter-Korean Summit

The third inter-Korean summit was remarkable in a number of ways. It started with an allegedly spontaneous move: the two leaders, hand-in-hand, jointly crossed the demarcation line and ventured into North Korean territory, before returning to the Southern side in the same fashion. Depending on one’s perspective, this gesture might not be seen to have been as innocent as it seemed. In the end, Kim Jong-un more or less forced Moon Jae-in to visit North Korea, making this the fourth such event in a row.

When looking at the details, it was interesting to observe how differently the two leaders dealt with the low concrete barrier that separates the two Koreas: Moon made sure not to touch it, as we would expect from someone who has grown up in East Asia where stepping on doorsills is a cultural taboo. Kim Jong-un, however, did not follow this custom.

This could have simply been due to him feeling uncomfortable taking the required large step; it could also be interpreted as a sign of having had an upbringing in an extraordinary environment in which the rules that apply to most other Koreans did not apply. The latter, if true, would be an important piece of information for upcoming negotiations, in which the personality and the mood of this decisionmaker plays a major role, especially since Kim Jong-un is evidently much less subjected to checks and balances by institutions as is typically the case in liberal democracies.

The two leaders signed the Panmunjom Declaration. It includes great many noteworthy points. These include the promise of no more war on the Korean Peninsula; the establishment of a liaison office (the equivalent to an embassy); joint participation in the 2018 Asian Games; meetings of separated families; modernization of railways along the east and west coasts of the peninsula; cessation of the propaganda war in the Demilitarized Zone; a peace regime for disputed waters in the West Sea; non-aggression and gradual disarmament; and a visit by Moon Jae-in to Pyongyang in autumn 2018.

The establishment of a peace regime to effectively end the Korean War was also included in the Panmunjom Declaration—but in a somewhat awkward manner. In a very complicated formulation, it was hinted that related talks could be either three-way or four-way—the two Koreas plus the United States and perhaps (or perhaps not) China. This is odd, because China is one of the signatories of the Armistice Agreement and thus must be a party to such talks if they are to produce a legal document ending the Korean War.

In case the implicit message was “Beijing, we are willing to sideline you if you don’t behave,” it is hard not to regard this as offensive. Another interpretation of this passage is less confrontational; it argues that an end-of-war declaration is mainly a matter of the two Koreas, that the United States joining such a declaration would be a first step towards establishing a security guarantee for the North, and that a formal peace agreement would be a different story having to be negotiated separately, and involving all signatories of the 1953 armistice agreement. In any case, Chinese media initially omitted the condition and only reported about four-party talks, but now seem to have switched to the second interpretation.

The most internationally noted point was the “common goal of realizing, through complete denuclearization, a nuclear-free Korean Peninsula.” As discussed above, this should be understood more as a symbolic and ideal goal for the distant future.

The problem with such formulations is, however, that they create expectations of more immediate actions. The North Korean side knows that and will most likely take steps that could, with the necessary goodwill, be interpreted as leading in this direction.

A largely overlooked formulation in the declaration was “80 million Koreans.” This looks very much like a North Korean phrase that has made its way into a document that will be quoted and cited over and over for the next years, if the experience with previous summit declarations can serve as a guide.

What is the problem with “80 million?” Simply put, it is part of North Korea’s strategy to take over control of the country during and after a unification process. “80 million” includes Koreans in North Korea and in South Korea, but also those “living abroad.” According to the North Korean viewpoint, this refers mostly to ethnic Koreans living in Japan, many of whom are organized in a pro-North Korean organization called Ch’ongryŏn in Korean, or Chōsen Sōren in Japanese. If a negotiated unification ever happens, the North Korean blueprint envisions setting up various committees and subsequently a joint parliament and a joint government staffed equally by all three groups. In other words, North Korea would control two thirds of representative voices and South Korea, despite its 50 million citizens, would find itself in a minority position.

It is unclear whether the South Korean side was unaware of the implications of the “80 million” formulation or whether it simply let the North Koreans have their way, expecting that this formulation will never become really relevant. In any case, this little example shows how competitive and tough the relationship remains between the two Koreas. This is a propaganda war, with summits and declarations as major

battle episodes.

Unusual Unorthodoxy

In this brutal soft power war, where nice words and friendly gestures are mere weapons, South Korea is under constant threat of either being sidelined or ending up between two fronts. Moon Jae-in has done well so far by taking the initiative in 2018 and using the chance offered by North Korea declaring that it is entering the next phase of its development strategy, as well as the symbolism offered by the Olympics.

Perhaps this unusually proactive behavior of the Blue House, which would typically enlist White House support first before making major offers to North Korea, was one of the effects of the Trump presidency. South Koreans are rightly worried about the effects of “fire and fury” and “total destruction” on their own country and people.

The United States will eventually face a global uphill battle for relevance, after its partners and allies have overcome their current initial shock and developed new strategies to deal with the new cold wind blowing out of Washington. For many decades, it seemed simply unthinkable to have any major international policy, be it in trade or defense, without the United States. But with Donald Trump destroying established procedures and certainties one by one, the search for alternatives has begun.

It seemed for a while as if the Korean peninsula would be one of the first instances of such a new paradigm, whereby the regional players would be willing to proceed without involving the United States. This would have placed the Americans in a very uncomfortable situation.

But the South Koreans saved the United States from such a scenario—at least for the time being. On March 8th—one day after visiting Kim Jong-un in Pyongyang in preparation for the inter-Korean summit—Chung Eui-yong, the South Korean national security director, was sent to Washington to brief Donald Trump directly. He conveyed the message that the North Korean leader was willing to meet the American president.

To the great surprise of most observers, including key American politicians, Chung was not just told that Trump accepted the invitation, but was also asked to inform the public about this historical change in policy. White House staff barely managed to prevent the related press briefing by a foreigner taking place inside the building—which would have been a major political faux pas—and hurled Chung and his entourage to the lawn outside the presidential mansion. But the fact remains that the first ever summit meeting between the United States and North Korea was announced by a South Korean.

During this episode, as well as during the following weeks, a remarkably humble approach by the South Korean side could be observed. Moon and his staff went out of their way to engage in what the Washington Post called “Seoul’s deliberate efforts to flatter the American president.” Chung Eui-yong was quoted as saying “I explained to President Trump that his leadership and his maximum-pressure policy […] brought us to this juncture.” After the April 27th inter-Korean summit, in an effort to secure what had been achieved and not lose the momentum, the South Korean president even suggested that Donald Trump should be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts to end the standoff with North Korea over its nuclear weapons program. Trump took the bait, and less than a week later 18 Republican lawmakers formally nominated him for the prestigious award. In hindsight, Moon’s strategy worked.

The South Korean president has understood an important lesson from history: namely, that even the most harmonious and productive inter-Korean relations will be useless without American support. If Washington is not forthcoming, the only alternative would be to break old alliances and form new ones. South Korea is not ready for that—and neither is China, at least for now. When Donald Trump called off the summit on May 24th, Kim Jong-un and Moon Jae-in met almost instantly and without much media spotlight, this time on the Northern side of Panmunjom, on May 26th. A few days later, Trump declared that he had again changed his mind.

Much Ado about Nothing?

Kim Jong-un knew he had to offer Trump something to keep him interested, but also needed to avoid the impression of making too many concessions at the Singapore summit. In the end, and despite all differences in the details, domestic politics matter as much in North Korea as elsewhere.

The solution to this dilemma was to formally separate the two issues. North Korea took confidence-building measures before the summit, so that they would not necessarily have to be interpreted in a causal manner. For instance, on May 9th, North Korea released three detained American citizens. Two weeks later, on May 24th, in another highly symbolic move, North Korea blew up its nuclear test site at P’unggyeri.

Despite initial doubts and a last-minute threat by Donald Trump to opt out, the first ever meeting between the leaders of North Korea and the United States took place in Singapore on June 12th, 2018. It resulted in widely broadcast images of the leaders smiling, shaking hands, and signing a document.

The Singapore Joint Statement was short compared to the Panmunjom Declaration. Using very general language, the two leaders vowed to improve bilateral relations between the two countries, build a peace regime on the Korean Peninsula, and “work towards” the complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula. A much more specific item was added at the end, stating the commitment to recovering the remains of American soldiers from the Korean War.

This latter commitment not only includes the remains of those missing in action, but also of prisoners of war. Resolving their case is, typically, a step that takes place after the conclusion of a peace treaty. It can thus be speculated that the two leaders agreed to something of this kind during their talks, even though it was not explicitly laid down in writing. The North Korean delay, in mid-July 2018, of the practical steps leading to the repatriation of some of the already identified remains points to the direction of a promise that was expected to be fulfilled but not honored by Washington. This assumption is supported by the fact that, around the same time, North Korean state media used some rather harsh language in response to allegations of a clandestine uranium enrichment plant near Kangsŏn.

The Singapore Joint Statement was instantly criticized by Western media for its lack of specific arrangements regarding the central issue from an American perspective: the nuclear problem. The formulation “work towards” denuclearization points to a direction that was later confirmed by Donald Trump: that this would be a long and complex process. This realistic and sober assessment of the situation is shared by most serious analysts.

Read together, the Panmunjom Declaration and the Singapore Joint Statement imply a certain sequential arrangement. Denuclearization, however vague and unspecific, is only mentioned after points referring to, in this order: (1) the improvement of bilateral relations and (2) the formal end of the Korean War (capped by a peace treaty). This causality is not made explicit, though given the hours of brainwork and negotiations that typically go into every sentence of such documents, the order of appearance in the two documents must be interpreted as deliberate and meaningful.

It is thus difficult to argue that the Singapore meeting produced nothing. One could go further: even the ambiguous formulations and their general nature can be interpreted as a success. Indeed, sometimes less is more. The two leaders refrained from acting impatiently. A problem that has had over 70 years to develop cannot simply be solved by one meeting and through one joint statement. On the contrary; the attempt to achieve something to that end is bound, with the highest certainty, to lead to failure. There is ample evidence of such a risk when looking to the past, including the aforementioned Leap Day Agreement of 2012, the Joint Statement at the Six Party Talks of September 2005, and even the Agreed Framework of 1994.

Ambitious agreements are difficult to keep, and are easily used as a justification by either side to accuse the other of having broken or not properly honored promises made and accepted in good faith. A first step is the precondition for steps two and three, and all others that follow.

By playing it safe and laying a solid foundation, rather than trying to achieve too much too early, Kim and Trump behaved in a highly responsible way that does not correspond with the image of the two that is usually projected in the media.

China is Back

One of the less publicly noticed aspects of the 2018 summit processes was the return of China to Korean Peninsula politics. This is not to say that China has ever really been absent; for two decades, it has actively and successfully supported the gradual marketization of North Korea that has produced stunning results. These have included the emergence and continued growth of a North Korean middle class, a re-monetization of the economy, and the spread of familiarity with the etiquette and side-effects of a market economy, including fair and unfair competition, advertisements, greed, and corruption.

Since 2013, however, Beijing has increasingly found itself in a situation of having no other option but to support international sanctions. The late 2013 removal of Jang Song-taek, who was often characterized as Beijing’s man in Pyongyang, further weakened China’s influence, despite it being responsible for about 90 percent of North Korea’s foreign trade. But the relevance of that trade itself needs to be questioned, as does China’s willingness to bear the consequences of a North Korean collapse resulting from a complete cut-off of all economic exchanges. The days when China hosted the Six Party Talks were over. Initiatives were set elsewhere, and, oftentimes, Beijing could only react.

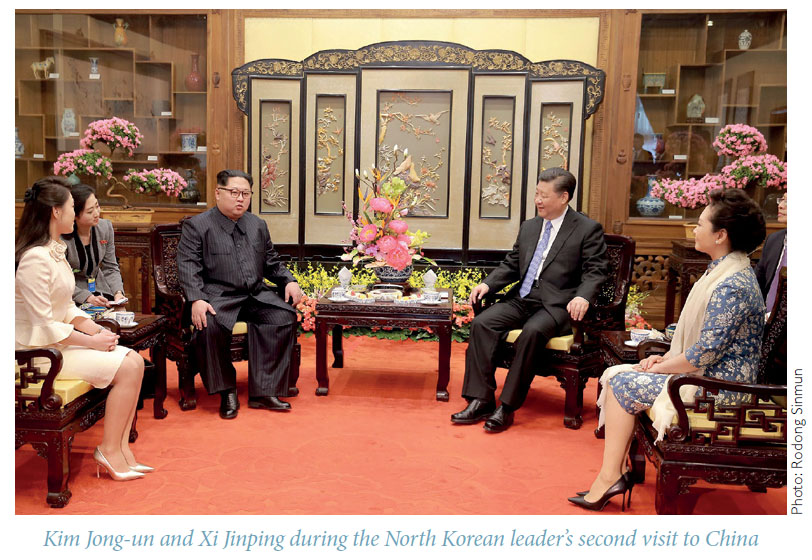

It is too early to say where this could lead, but it must be noted that China has become much more active. On March 25th, 2018, Kim Jong-un traveled to Beijing for three days to meet with China’s President Xi Jinping—the first ever meeting between the two leaders since Kim Jong-un came to power in 2011. In fact, it was Kim’s inaugural foreign visit as his country’s leader.

One could point to the significance of the fact that the North Korean media called this meeting “unofficial;” on the other hand, not only did it take place, but it was widely reported in the same media. A commemorative stamp was even issued swiftly in North Korea, which is an indicator of importance. Furthermore, images of the leaders and their respective First Ladies conveyed the impression of a harmonious and personal relationship. This was a striking departure from earlier open accusations heard in North Korea of China being a traitor to the long-standing alliance.

On May 7-8th, after the meeting with Moon and before the Singapore summit, the next Kim-Xi dialogue took place in Dalian.

Against the backdrop of a rediscovered strategic partnership, Beijing provided an Air China Boeing 747 jumbo-jet to Kim Jong-un for transport to Singapore. Most strikingly, the North Korean state media did not just show photos of their leader leaving and entering an airplane with a huge Chinese flag painted on it; in a quickly released official video of the Singapore summit (it had a running time of about 45 minutes), the narrator explicitly mentioned that the North Korean leader had traveled to Singapore “aboard a Chinese airplane,” as if to make sure that this point was not overlooked by his North Korean audience.

On June 19th, Kim Jong-un again traveled to Beijing, obviously to discuss the results of his meeting with Trump. Xi had earlier assured Kim of his intention to visit Pyongyang in late 2018, which is regarded as a major gesture of respect and cooperation. It is to be seen how far all this will go; China still is the main threat to all aspects of North Korean security, though it is at the same time North Korea’s best option to keep the Americans at arm’s length. One recalls the sage advice proffered to the Koreans in the late nineteenth century by the Chinese statesman responsible for directing his country’s policy towards Korea, Li Hongzhang: fight poison with poison.

The Road Ahead

It does not require much creativity to imagine that Kim Jong-un wants to repeat the game that his grandfather Kim Il-sung played so successfully in the 1950s, when he manipulated two superior powers, China and the Soviet Union, played them off against each other, and extracted enormous economic, military, and political benefits from this process.

So far, North Korea has been doing remarkably well. After years of almost complete international isolation, in the first half of 2018 Kim Jong-un had a total of six summit meetings with the leaders who are most relevant for his country, including the two global superpowers. Similar summits are being discussed or prepared with Vladimir Putin of Russia and Shinzo Abe of Japan. Follow-up meetings with Moon and Xi in Pyongyang have already been announced for the third and fourth quarters of 2018. When all is said and done, Kim’s summit score in 2018 could easily rise to ten or even more. Appearances of the North Korean leader at high-level international events, like the UN General Assembly or the World Economic Forum in Davos, seem to be a realistic option for the future.

Despite all the progress recorded in the first eight months of 2018, we are still standing at a crossroads. In the United States, the current situation makes for strange bedfellows: liberals who oppose Trump find themselves in agreement with hawks who oppose any negotiated solution with North Korea that falls short of an unconditional surrender. Should the American president fall from power (or not get reelected), then a policy of “Anything-But-Trump” would likely become the mantra of his successor.

Speed is thus crucial. This does not contradict the earlier support of a gradualist approach—one that spans more than just one electoral period. In addition to Trump’s political half-life, a lot depends on how long the United States and North Korea will be able to postpone the moment at which their differing goals and interpretations finally come to the fore.

That such a conflict will come is almost certain, but what has been achieved until then will determine whether this moment of awakening will lead to a return to the bellicose status of 2017, or whether the progress made until that point can be preserved to mark a new normal.

Such irreversible achievements would include a peace treaty to formally end the Korean War and the establishment of diplomatic relations between Washington and Pyongyang.

Everything else—the removal of sanctions by the United States and the UN, or a freeze of North Korea’s nuclear program, a moratorium on testing, and a commitment to non-proliferation, nuclear safety, and inspections—can be easily retracted. Pyongyang might agree to the public dismantlement of one or two missiles and nuclear warheads, but it could insist on the right to retain a critical number of nuclear weapons. Even such a move would, in essence, be mainly symbolic, because the remaining arsenal would still be seen as a threat by the United States, and because a frozen program can be restarted to produce new weapons.

As with all international agreements, the key to success is thus to keep the benefits of maintaining the agreement higher than the benefits of breaking it, or to keep the costs of breaking the agreement higher than the costs of maintaining it. In other words, a comprehensive approach is needed to make North Korea a stakeholder in an ongoing denuclearization process.

Given the previously discussed prerogatives of Kim Jong-un, this will have to involve a number of economic incentives. They might over time even improve the effectiveness of another round of “maximum pressure.” As shown by the case of Iran, a country that is to a certain degree integrated into the global economy will value the costs of losing this access much higher than a country that has almost no international connections anyway. The best bet of the West is to keep the current process going, no matter how slowly, and to expect the changes in North Korea that were begun two decades ago to continue and create new realities.

This is a long shot, to be sure, although the examples of China, Vietnam, and Cuba demonstrate the possibility of success. In any case, it is a process that cannot be centrally planned and predicted in all its details. Most crucially, it will take much longer than just one or two election periods. It will require a strong sense of responsibility—especially among leaders of democratic states who know that they might pay the price during their time in office for a return on investment that will be accrued by one of their successors, and, in the worst case scenario, by a domestic political opponent.

Accordingly, there are two dangers to the process of reconciliation on the Korean peninsula. The immediate, short-term danger is that Trump changes his mind and decides that diplomacy has failed, or that he leaves office soon and all his initiatives are undone as a matter of principle. The longer-term danger is of a more structural nature and is related to the difficulties electoral democracies have with policies that will not produce instant returns for their creators.

The solution to this dilemma is to set realistic intermediary goals or waypoints, including all the necessary attempts to make successes as sustainable as possible once they are reached. A policy of small steps, guided in the background by a grand strategy that is flexible enough to accommodate adjustments as events progress, seems to be the most realistic option for such an outcome.