Uwe von Parpart is the publisher of the Asia Times newspaper.

Uwe von Parpart is the publisher of the Asia Times newspaper.

Historically, when the largest European powers of the modern period, Russia and Germany/Prussia, were at peace with each other, their peoples and economies thrived, and the continent’s cultural and scientific achievements led the world. Conversely, when they and their allies were at each other’s throats, Europe descended into barbaric slaughter, enormous loss of life, and physical destruction of what generations had built.

Statesmen and women, of East and West (if there be any), charged with settling the world’s current pivotal conflict, focused on Ukraine, would do well to review the Russia-Germany relationship to gain a point of perspective.

How it used to be: Russian energy in exchange for Germany's high-technology manufactured goods / Source: Shutterstock/Mikhail Mishunin

Over a century of peace and cooperation between the sides, a few minor tiffs aside, was ushered in on December 30th, 1812, with the Convention of Tauroggen (now known as the town of Taurage in Lithuania) when Prussian General Ludwig Yorck negotiated with Carl von Clausewitz, then in Russian service, to switch sides with his Prussian corps from Napoleon’s Grande Armee to the Russian Imperial Army. Within a year and three months, by March 31st, 1814, the coalition forces of Prussia and Russia joined by an Austrian contingent had expelled Napoleon from all German lands and the victors, headed by Czar Alexander I and Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm III, marched into Paris.

Subsequently, the Congress of Vienna, held between September 1814 and June 1815, chaired by Austrian foreign minister Prince Metternich, re-confined France to its pre-revolutionary and pre-Napoleonic wars borders, and established a system of balance of power between Prussia (and later Germany), Russia, Austria, and Britain (and after 1818, France), which contained conflicts among members and protected Europe from large-scale and protracted wars for almost a century.

The key element in the system was avoidance of conflict between Prussia/Germany and Russia. The key statesman who saw to it and whose diplomatic skills and wiles accomplished the nearly impossible, in particular, after the disruptive establishment of a unified Germany in 1871, was Otto von Bismarck.

He was a descendant of a family of Pomeranian landed aristocrats (junker), but had trained as a lawyer and joined the Prussian civil service. In 1848-1849, he eloquently condemned the attempted 1848 republican revolution, positioned himself as an archconservative loyalist of the monarchy and was elected to the Prussian Chamber of Deputies, the lower chamber of parliament. In 1851, King Friedrich Wilhelm IV appointed him as the Prussian representative to the Frankfurt Federal Assembly.

While in Frankfurt and dealing with the mundane affairs of the German Confederation, often in conflict with the Austrian representatives, Bismarck retained his trademark ultraconservative outlook, but along with it adopted the uncompromising realpolitik approach that in his later career earned him the “Iron Chancellor” moniker. To put it in contemporary terms, he was no neocon ideologue.

In 1859, to his initial disappointment, Bismarck was appointed as Prussian ambassador to St. Petersburg. But he quickly realized the excellent opportunities inherent in the position. He gained the respect and trust of Czar Alexander II. They conversed in German; Alexander’s mother was Charlotte of Prussia. When Bismarck left Russia in 1862, he was certain of the czar’s friendship with Prussia and of his support of Bismarck’s next big project, the unification of Germany under Prussian leadership. “We wish for a strong and unified Germany,” Russian Foreign Minister Gorchakov told him. “We need Germany to realize our own political aims.”

In May of 1862, for what proved to be a brief stint, Bismarck became ambassador to France, only to be recalled to Berlin in September by new King Wilhelm I to serve as Prime Minister and Foreign Minister.

Two wars, against Austria in 1866, and against Napoleon III in 1870-1871 followed. Both of them were won by Prussia. In neither of them did Russia intervene. The Franco-Prussian War led to the crowning of Wilhelm I as Emperor and Bismarck as Chancellor of a unified Germany. For another 20 years Bismarck was the guarantor of peace in Europe. Asked about the success of his policies, he said, “The secret of politics? Make a good treaty with Russia.”

Fast Forward to War

In 1888, Wilhelm I died as did his son Friedrich III, the 99-day emperor. Emperor Wilhelm II, age 29, as inexperienced as he was arrogant, soon came into conflict with Bismarck and on March 18th, 1890, forced him to resign.

Under his successors, the Bismarck treaty system rapidly unraveled, most importantly the critical Reinsurance Treaty with Russia, which expired in 1890 was not renewed. In 1891, Russia made treaty overtures to France and a secret Franco-Russian treaty followed in 1894. In 1904, the Anglo-French Entente Cordiale was concluded. The German Empire was now surrounded, with only the moribund Austria-Hungary as an ally and a major liability due to its Balkan entanglements that Bismarck had always made a point of avoiding.

Bismarck died in 1898. Twenty years later, the empire he founded was no more. Nor was the Russian Empire, and 2.3 million Russian and 2 million German soldiers were dead. World War II that followed saw 5.3 million German military deaths, most on Russian soil, and an enormous 11.4 million dead Russian soldiers.

A Note on Mackinderism

On January 25th, 1904, Halford Mackinder, Reader in Geography at Oxford and Director of the London School of Economics, delivered a lecture entitled ‘The geographical pivot of history’ at the Royal Geographical Society of London. It proved controversial and influential in equal parts. Controversial because it challenged the prevailing British (and American) orthodoxy of the supremacy of maritime power articulated by Alfred Thayer Mahan in the 1890 “The influence of sea power upon history.” Influential because the Mackinder thesis that sea power was losing out to land power made it urgent for balance-of-power obsessed British strategists to counter any potential German-Russian (“heartland”) alliance by all means.

Was British Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey ultimately swayed by such considerations to enter World War I? Surely, he will have considered the possibility that Germany might defeat Russia and France if England did not intervene.

Fast Forward to the Present

While Mackinder-type considerations may not have explicitly entered into Grey’s decisionmaking in the crucial days of late July through August 4th, 1914, surely ever since the Hitler-Stalin pact and up to the present, the possibility of a German-Russian alliance that would dominate Europe and reach well into Asia has been an Anglo-American strategic nightmare.

NATO was founded for that very purpose, or as NATO’s first secretary general—Britain’s Lord Ismay—felicitously expressed it, it’s purpose is “to keep the Soviet Union out, the Americans in, and the Germans down.” And thereby we have arrived smack in the middle of today’s world and the critical question of how to assess the causes of the Ukraine war and how to end it before it ends us.

The issue, of course, is not only how to silence the guns, but to achieve what the Congress of Vienna achieved, helped along by Bismarckian diplomacy: a century of peace.

Russia and the Second German Unification

The Berlin Wall fell on November 9th, 1989. On March 18th, 1990, the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) held it’s first free elections. The newly elected parliament (Volkskammer) passed a resolution on August 23rd, 1990, declaring the accession of the German Democratic Republic to the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany). The Unification Treaty came into effect on October 3rd, 1990. The Treaty on the Final Settlement Concerning Germany, in short 2+4 Treaty, was concluded on September 12th, 1990, in Moscow between the two German states and the victorious powers of World War II (the United States, the Soviet Union, France, and the United Kingdom) and enabled formal unification and the return of full sovereignty of the German state.

It is of interest that the Soviet Union under Gorbachev and the United States were most readily fully supportive of unification. France and the UK showed a great deal of reluctance.

All Soviet troops were also readily withdrawn from the former East Germany. NATO troops remained in the former West Germany since the re-unified country remained a NATO member.

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union as a sovereign state on December 26th, 1991 and the creation of the Russian Federation, the path should by now have been cleared for the establishment of normal relations between Germany and Russia. But this did not come to pass, in part because it could not be expected to change overnight from a Communist country with a centralized, dirigiste economy into a free market economy on Western models.

As this process dragged out and political instability and uncertainties over the relationship of Russia to the other newly independent republics of the former Soviet Union prevailed, there was an urgent need to define, negotiate, and implement new equitable East-West security structures.

There is no evidence that any such efforts were made. Instead of following the Bismarck model to “make a good treaty with Russia”, the United States under the Clinton Administration (1993-2001) began the process of inviting former Soviet republics in batches and one-by-one into the U.S.-led NATO alliance. Similarly, the EU appears to have made no effort to engage Russia and develop closer economic ties.

From NATO Expansion to the Ukraine War

Two rounds of NATO expansion dated March 12th, 1999, and March 29th, 2004, brought ten former Eastern bloc nations and ex-Soviet republics into NATO’s fold. Another six members were added between 2009 and 2023-2024 (which is when Sweden and Finland were admitted). Membership applications by Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, and Ukraine are pending.

We need not review the details here; but when—supported by U.S. administrations with starkly neoconservative foreign and security policy personnel—first the Orange Revolution of 2004 and then the 2014 Maidan uprising occurred in Ukraine, Russian President Vladimir Putin decided to wait no longer and strike back against NATO encirclement cum regime-change threats. According to former German Chancellor Angela Merkel (2005-2021), the Minsk agreements were never intended to be implemented but only to buy time to arm Ukraine and develop a capable military. Bismarck—or for that matter, Henry Kissinger—could have foretold the outcome when Russia is cornered in such a fashion.

The Destruction of the German Economy

Whether the intended outcome or collateral damage or—most likely—some of both, not only Russia has been substantially weakened by the outbreak of open warfare in Ukraine, the damage to Russia’s best strategic economic partner, Germany, has been at least as, if not even more, severe.

The partnership, quite rationally based on the supply of Russian energy and raw material resources in exchanged for high-technology manufactured goods and plant and equipment for Russian industry, has been destroyed much like the Nordstream gas pipelines under the Baltic Sea—an event accurately “predicted” by U.S. President Joe Biden in a Washington news conference with German Chancellor Olaf Scholz.

Here are some key elements of the damage report:

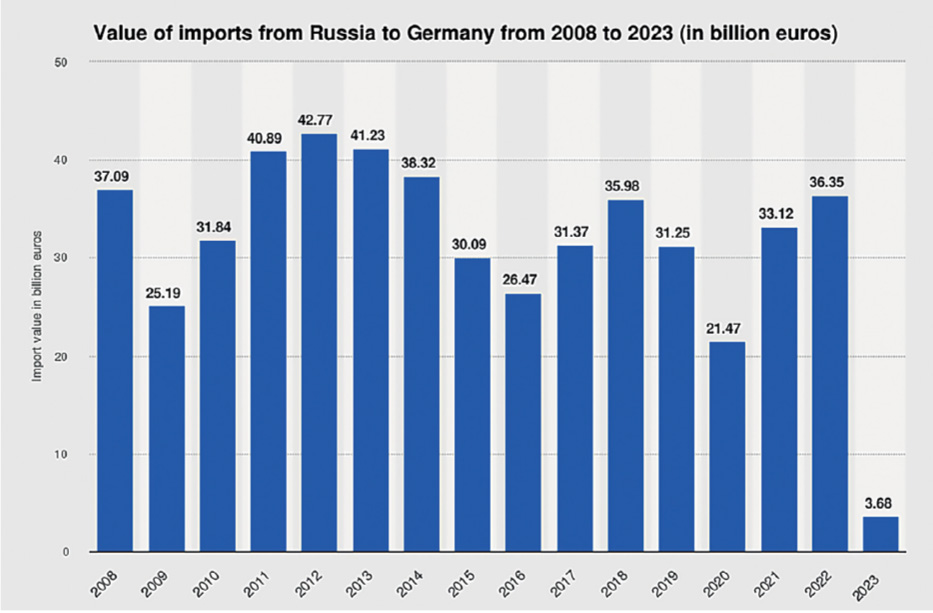

Imports from Russia to Germany and exports to Russia from Germany have collapsed. The two charts below speak for themselves.

Source: www.statista.com

More importantly, German industrial electricity prices have shot up and make production in Germany unprofitable. German companies, if they invest at all, have shifted investments abroad.

Source: www.statista.com

Critical energy intensive industries in Germany have had to cut production massively.

The overall German business climate is on a continuing downward slope. The German economy, as the powerhouse of Europe has seen two consecutive years of negative growth. Zero growth in 2025 is the best to hope for. The German is the EU’s worst.

These pieces of data demonstrate the negative impact of the Ukraine war. Conversely, of course, were this war to end, then the Russo-German economic collaboration could make an enormous comeback.

That, however, presupposes a peace settlement in the context of a reliable new European security framework, a framework that must greatly reduce political risk in order to unlock the vast complementary joint economic development potential.

There is highly qualified Russian manpower potential aplenty to make this work. The Russian Federation graduates over 400,000 engineers per annum, the United States just 250,000—at over twice the population base.