Jakub Korejba is a Polish political scientist and Non-Resident Fellow at the Center for Eurasian Studies (AVIM) in Ankara. He is a Visiting Professor at the Faculty of History and International Relations at Université Saint-Joseph de Beyrouth and a Visiting Research Fellow at the Center for International Relations and Sustainable Development in Belgrade, Serbia.

Jakub Korejba is a Polish political scientist and Non-Resident Fellow at the Center for Eurasian Studies (AVIM) in Ankara. He is a Visiting Professor at the Faculty of History and International Relations at Université Saint-Joseph de Beyrouth and a Visiting Research Fellow at the Center for International Relations and Sustainable Development in Belgrade, Serbia.

It’s quite obvious that the war in Ukraine will result in a broader new confrontation in Europe. Russia and the West are not demonstrating any readiness for substantial concessions that the other side expects, and therefore, the relationship will remain tense. This tension will be particularly perceptible in Eastern Europe—a region where both antagonists are physically within reach of each other. The question is whether this confrontation will proceed in an organized or disorganized fashion. In other words, as part of an order or part of a disorder.

Neither Russia nor the West have achieved their strategic objectives during the active phase of the Ukrainian conflict. Russia is militarily far from controlling Ukraine and politically farther than ever from restoring a new version of the Soviet Union, of which Ukraine would be the first and most important element. The West has no clear prospect of transforming Ukraine into an exemplary incarnation of democracy, human rights, market economy, and society with efficient institutions. Both protagonists, willing to see Ukraine as an instrument of their own domestic and international legitimacy, and likely a training ground for their visions of the future, must accept that Ukraine will look like neither of their respective projects.

Ukraine does not, and will not for the foreseeable future, be able to fit into either Russian or Western political and institutional frameworks. Ukraine will not become a second Belarus nor a second Poland. It will remain something else in between, both from the point of view of its internal structure and its international functionality. Put in ugly but accurate geopolitical terms, Ukraine will remain a buffer zone between two autonomous, self-sufficient, and active centers of power. The aim of this article is to identify, reveal, and describe to the extent possible the consequences of this fact (the post-war status of Ukraine) on three levels: bilateral, regional, and supra-regional (continental, global).

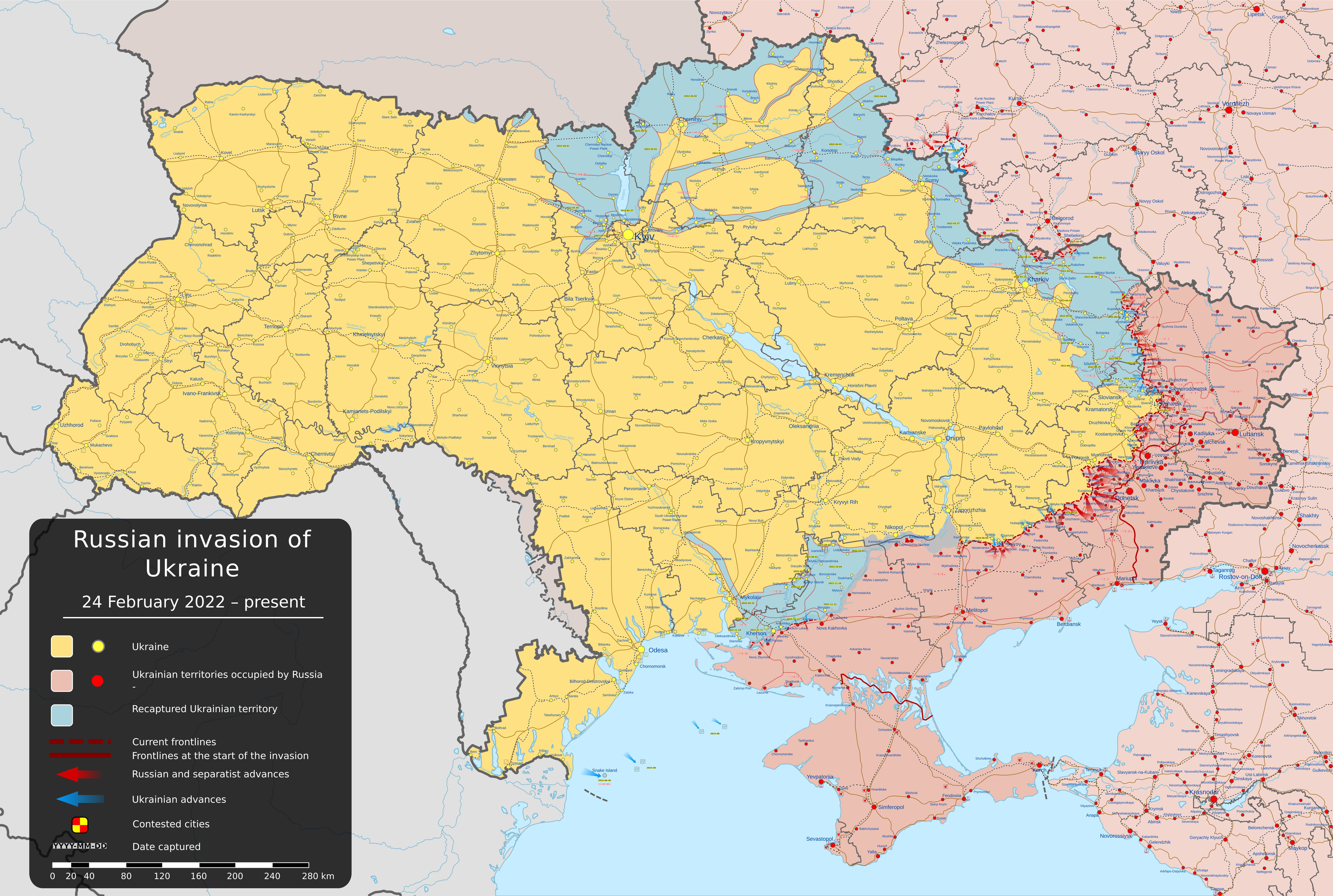

Territorial control in the main Ukraine theater as of January 2025 / Source: Wikimedia Commons

Territorial control in the main Ukraine theater as of January 2025 / Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Structure of the New Order

Independently of what the territorial outcome of this war will look like, Russia and Ukraine will remain neighbors for the foreseeable future. Willingly or not, they will have some sort of a relationship. It is hard to imagine that Ukraine will cease to be a state and disappear from the political map of Eastern Europe, and Russia is unlikely to implode and plunge into a civil war. Both countries will remain the closest geopolitical realities for each other. After fighting one war, both will be aware of how difficult it is to win it and thus probably won’t be eager to engage in another one. They will both want vengeance and what they see as a just peace, but will try to achieve it by political means, knowing how disastrous another war could be for their own states and societies. The current state of the war is not accidental: it reflects the existing power ratio between Russia and Ukraine and, as such, creates a balance of power that could potentially prove stable. Yes, Ukraine does not have enough political, economic, military, and cultural power to maintain the entirety of its territory in accordance with the 1991 borders. Still, it has enough to keep 80 percent of it. Similarly, Russia does not have the ability to conquer all of Ukraine. It has enough to capture 20 percent of Ukraine’s territory, as three years of this war have empirically proven.

Tolerating, if not respecting, the existence of a post-war buffer Ukraine will be in the best interest of Moscow, for it will constitute the only element of order in Eastern Europe that actually guarantees Russia the status quo. Obviously, the post-war outcome is far from what Russian strategists had designed and expected. Nonetheless, it is still much better than the full-scale confrontation with the West that could arise if Ukraine were to disappear. In such a scenario, the West could feel compelled to react due to a radically disturbed balance of power in the region, placing it at a clear disadvantage. If Russia is unable to win a war with Ukraine alone, it would stand very little chance of survival if confronted with bigger, wealthier, stronger, and better-organized antagonists. To avoid a direct confrontation with the West—as well as a murderous arms race that it would likely lose—Russia needs Ukraine as a buffer to guarantee at least the status quo until the end of the ongoing political cycle, which will take a maximum of another 10 to 15 years. Given the ongoing tendencies of internal and external factors, Russia will most likely face issues over the stated period that will, in comparison to Ukraine, seem rather minor.

The regional order—or the way Eastern Europe is organized—has been subject to numerous conflicts, including the two most spectacular and destructive world wars. If this much attention is devoted, and this amount of blood shed, just for the sake of influence in this part of the world, then it must mean that the order that takes hold in Eastern Europe ranks very high on the scale of international issues. Since the collapse of the bipolar world order, this region has been divided into two parts: Central Europe, included in the Western sphere of influence on the one hand, and Eastern Europe, predominantly influenced by Russia, on the other. The war in Ukraine did not change that structure. As neither side is able or willing to fundamentally transform Eastern Europe as a whole, the post-bipolar division will remain in place even after this war ends—no country in this region will change its strategic orientation. If the old order is not weakened or dismantled, it logically means that it will be strengthened: borders will be reinforced, contacts will be limited, the defensive potential on both sides will be enhanced, and the hope of a non-divisive peaceful convergence will be lost. In fact, all of that is already happening.

The division of Eastern Europe will remain a lasting foundation of the reality between Russia and the West. Both sides will be deeply distrustful regarding the future intentions of their geopolitical counterpart and, as a result, will continue to boost deterrence capacities along both sides of the border. Scandinavia, the Baltic states, Poland, and Romania on one side, and Belarus, the western oblasts of Russia, and the occupied parts of Ukraine on the other, will transform into highly militarized strongholds. This is nothing new for Eastern Europe, and historically speaking, this is the most natural way to exist between the West and Russia. The only known alternative is for the region to turn into a battlefield. Eastern Europe will not become a bridge, as there will be no two ends willing to meet. On the contrary, Russia and the West will need a buffer space, whose role will be to form an armed limitrophe that will guarantee—or at least increase the chances—that the sides continue to avoid a wider kinetic confrontation. Central-Eastern Europe will not emerge as one coherent sub-region of Europe. Central will be more Central, and Eastern will be more Eastern, each drawn by the forces of external influence. This will occur despite the dreams and ambitions of the peoples living on both sides of the new Iron Curtain. Russia and the West will not become one single strategic, economic, or cultural entity. They will instead remain separate and hostile, meaning that the border between them must lie somewhere. In strategic and human terms, it might even be optimal to leave it where it is. This especially rings true when one considers the lessons of Ukraine—i.e., what happens when either side tries to move the aforementioned border.

The structure and dynamics of the order in Eastern Europe have wider consequences—it is an important element of continental and global interaction. The fact that this mostly local war didn’t escalate into a continental or global one (despite at least a few such opportunities) proves that major acting powers had no interest in such an escalation. In fact, both the West and Russia have stuck to their red lines, limiting the physical damage to the internationally recognized territory of Ukraine without touching other elements of the shared borderland. The fact that Ukraine will not be incorporated into the Russian strategic structure means that Russia will not become a decisive power in Europe. Therefore, Moscow will not be able to maintain its status as a global power, while its power-projecting abilities relative to the United States and China will only decrease. In a wider perspective, Russia’s failure to control Ukraine is part of a broader process that is currently happening to all European powers, resulting in their loss of global influence.

All former European empires are experiencing a dramatic decrease in power, especially when compared to the U.S. and China—and there is no viable factor that may reverse this trend in the foreseeable future. France, Germany, and Italy have no capacity—and even less willingness—to organize Europe, let alone project power beyond their borders. The UK seems to have accepted the role of America’s junior partner long ago. Seeing the gradual disappearance of Europe as a geopolitical power center, the United States, China, and other emerging powers have no interest in letting Moscow dominate even parts of Europe, let alone all of it. A politically fragmented, strategically impotent, and ideologically disoriented Europe is beneficial for the U.S. and China, and if Ukraine and Russia decided to act as catalysts of those processes, Washington and Beijing would be irrational to miss out on the opportunity. Moreover, the establishment of a new Iron Curtain across Europe will be a highly efficient instrument for both countries in shaping the world order according to their respective interests. Seen from a global perspective, both Russia and Europe have failed to expand their zones of influence (by gaining Ukraine), which is just another tangible proof of their deep and fatal decadence.

The Consequences of the New Order

Ukraine is a country whose international identity is stuck between two mutually exclusive options. On the one hand, the social and cultural factors make the majority of its citizens reject the Russian model of development—or, more precisely, a model of existence, as there is not much development. On the other hand, because of the social and cultural pressures from parts of its own population, Ukraine is unable to transform itself into a country compatible with the Western formats of integration. It is true that Russian revisionist pressure—both from the outside and within Ukrainian society and institutions—is stronger than the one exerted on other Eastern European states. But ultimately, the EU and NATO’s membership criteria have been clearly established, understood, and well known for a long time. Those institutions were established to avoid seeing their member states become Soviet, and were subsequently expanded to make the actual post-Soviet countries less Soviet. By their design and the free will of their member states, they are inherently anti-Soviet and anti-Russian and will remain so for as long as Russia exists as a great power capable of expanding. The EU and NATO have no interest in becoming more post-Soviet by including Ukraine and will therefore not make any concessions regarding the conditions of its potential membership. If Ukraine wants to join, it will have to comply with the established rules. The situation in which Ukraine is willing to move away from Russia but unable to join the West creates a deep cognitive dissonance that both Russia and the West tried to resolve in the same manner. Namely, both tried forcing Ukraine into making an unequivocal choice—and in so doing, both have failed. The very evident lack of solutions to this clinch—which has mental and cultural roots much deeper and more complicated than those conditioned by strategy, economy, history, or geography—was not changed even during the momentum created by the war.

The West has had no existential difficulties in functioning without Ukraine as a member of its major institutional incarnations. Nothing will change in this regard in the future. Moreover, the West will continue to exist, develop, and expand perfectly well even without any contact with Ukraine. In fact, if it could survive and win the Cold War while being isolated from Eastern Europe in its entirety, it would surely be able to do so if the new Iron Curtain falls on the eastern border of Poland. The strategic significance of the Ukrainian territory is a function of the West’s relations with Russia. It matters in two extreme cases only: if the West expects Russia to invade it (which was the case during the Cold War but will not be for a long time now due to Russia’s weakness), or if the West expects to actively convert Russia and remake it in its own model (which is not the case, with the Ukraine war ultimately demonstrating how unrealistic this assumption was). If there is no ambiguity (for better or worse) in Russia-Western relations, stability is induced by the order, and in that case, control over Ukraine does not change the balance. In that case, other than a moral one, there is really no reason to try to change Ukraine’s development model.

From a Western point of view, every nation has the right to choose whether it wants to live in a democracy, a market economy, and governed by efficient institutions. If the Ukrainians make a choice in favor of the Western model, they are free to do so. But in this particular case, the price is higher than for any other Eastern European nation, and it is up to the more interested party to the deal to pay it. The West has imposed no obstacles to Ukraine joining the EU and NATO, other than meeting the standards that all aspiring post-communist countries had to meet before being admitted as members. If Ukraine didn’t follow the path of Poland or Romania, this would turn out to be more problematic for Ukraine than for the West. If Ukraine had met those requirements at any stage of its independent history, the West would have had no option but to use all its potential to secure the process of Ukrainian membership, just as it did with all other states, including those whose geostrategic position is more important for Russian security than Ukraine’s. If Ukraine doesn’t demonstrate its ability to become compatible with the West by meeting the standards, the West can wait. Meanwhile, the West can also adapt psychologically and militarily for the event in which Ukraine’s nature as a buffer state morphs into Russia’s zone of influence. Historically, Ukraine has already been in Russia’s zone of influence, which was definitely bad for Ukrainians but bearable for the West. If the choice to move the new Iron Curtain eastward is to be made, this will have to be done in Kiev, not in Washington or Brussels.

But history also shows that Russia can live without Ukraine as well. Three years of military efforts to liquidate Ukrainian statehood has produced a very moderate result, which has further instilled a clear understanding that tolerating Ukrainian independence is cheaper than trying to suppress it. Given the lack of moral and material resources, Moscow cannot realistically expect to include Ukraine in its entirety into some renewed version of the empire. Therefore, transforming it into a buffer zone that isolates itself from the West seems to be a reasonable compromise between geopolitical dreams and reality. No one in the West can sincerely guarantee to Moscow that Ukrainians will not try to adopt the Western model, including by organizing a new revolution against a regime that rejects it by trying to keep an equal distance between Russia and the West. This is because the reason for Ukraine’s rejection of Russia comes not from the West but from within Ukraine itself, and the will of a nation remains a factor in international relations.

Previous anti-Russian revolutions in Ukraine were not initiated by Western activity, but by Russia itself and the fact that its model appears comparatively less attractive to Ukrainians. And as long as Russia continues to cling on to its obsolete economy, dysfunctional social system, and a general lack of civilizational appeal, the contrast between itself and the West will remain evident to Ukrainians and will motivate them to reject Russia’s influence. One day, a new Iron Curtain will rust and fall just as the old one did, due to the fact that nations have the right and means to make the choice between alternatives proposed to them by competing centers of civilization. And given the influence of mass communication (both online and offline) that Ukrainians have access to, this will happen sooner rather than later, unless Russia itself starts to look like an attractive option. The West may declare that it will not interfere actively and (explicitly or implicitly) halt Ukrainian membership in the EU and NATO, but it cannot guarantee any level of support to Moscow inside Ukraine, as well as in any part of the post-Soviet space, including the Russian Federation itself. The West has no reason to act against its own interests, especially if those interests align with values. It cannot say to Ukrainians that they have no right to adopt a model they actually perceive as the best of the available options.

Lessons in Realism

All three stakeholders of the ongoing confrontation (Ukraine, the West, and Russia) have the opportunity to learn a lesson in realism. The Ukrainian conflict, and especially its kinetic phase that started in February 2022, demonstrated the practical limits of existing conceptions: it is already clear that neither a Greater West nor a new Soviet Union will materialize in the form of a geopolitical reality. Therefore, if neither the Western nor Russian conception of Eastern Europe is practically feasible, the new post-war order will have to be based on something else. This cannot be any transitional option, as both models have mutually exclusive natures: the last three decades of Eastern European history demonstrate that a stable coexistence of those models in one country is impossible, and the choice has to be made. This region has always been and will remain divided, and the question is only where exactly the border between the two ‘civilizations’ (to synthetically put the problem in Huntingtonian terms) will physically lie. To make the solution sustainable and allow it to enhance order rather than spur chaos and new conflict, the West must accept that its model stops at the western borders of Ukraine, while Russia’s model stops at the eastern ones. The question of the remaining territory ‘in between’ remains open, but if both sides have an interest in peace, they must agree not to attempt to actively change the balance inside the post-war buffer Ukraine. Thus, forming a vast no-man’s land between the two centers of strategic and civilizational influence will be key.

This type of resolution is certainly ugly in comparison to the beautifully drawn concepts that both Russia and the West have previously had for Eastern Europe, but it is hardly more immoral than continuing to kill each other. Eastern Europe will not look like the West wanted, nor will it look like Russia wanted. Ukraine will not look like pro-Western Ukrainians wanted, nor will it look like pro-Russian Ukrainians wanted. The new order in Eastern Europe will be based on a new Ukraine. Otherwise, there will be no order at all, with all the deplorable consequences for all sides. Ukrainians are the ones who risk losing the most because they are right in the center of this disorder: it is they who are actually losing their lives, homes, and infrastructure. Being a buffer country is certainly better than not being a country at all, and losing territory does not terminate the state- and nation-building process. On the contrary, the example of several Central and Eastern European nations demonstrates that there is life after territorial losses, and this life can actually be better than before. This fact doesn’t make Russian expansionism, militarism, and imperialism any more moral or legal. It’s a simple observation that other factors exist and play—sometimes more dominant—roles in the everyday existence of nations that happen to be Russia’s neighbors. If Ukraine could restore its territorial integrity, it would have done so already. Since it has not, it is probably not realistic to expect it to, given the crystal clarity of the panorama of positive and negative factors that actually form Kiev’s decisionmaking framework.