Samir Khleif, a board certified medical doctor in internal medicine and medical oncology, is Director of the Georgia Cancer Center at Augusta University. You may follow him on Twitter @SamirNKhleif.

Samir Khleif, a board certified medical doctor in internal medicine and medical oncology, is Director of the Georgia Cancer Center at Augusta University. You may follow him on Twitter @SamirNKhleif.

One of the most important strategic questions regarding the implementation of the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development is financing. Various treaties, accords, resolutions, and other such multilateral documents underscore the essential need for greater resource mobilization across the globe. As it was put in an ambitious statement released in 2015 by the heads of some of the world’s most established international financial institutions: we need to move from

billions to trillions in resource flows. Such a paradigm shift calls for a wide-ranging financing framework capable of channeling resources and investments of all kinds—public and private, national and global.

In other words, public finance mechanisms can no longer carry the development burden alone. Incentivizing the private sector has become one of the twenty-first century’s new imperatives of financing for development.

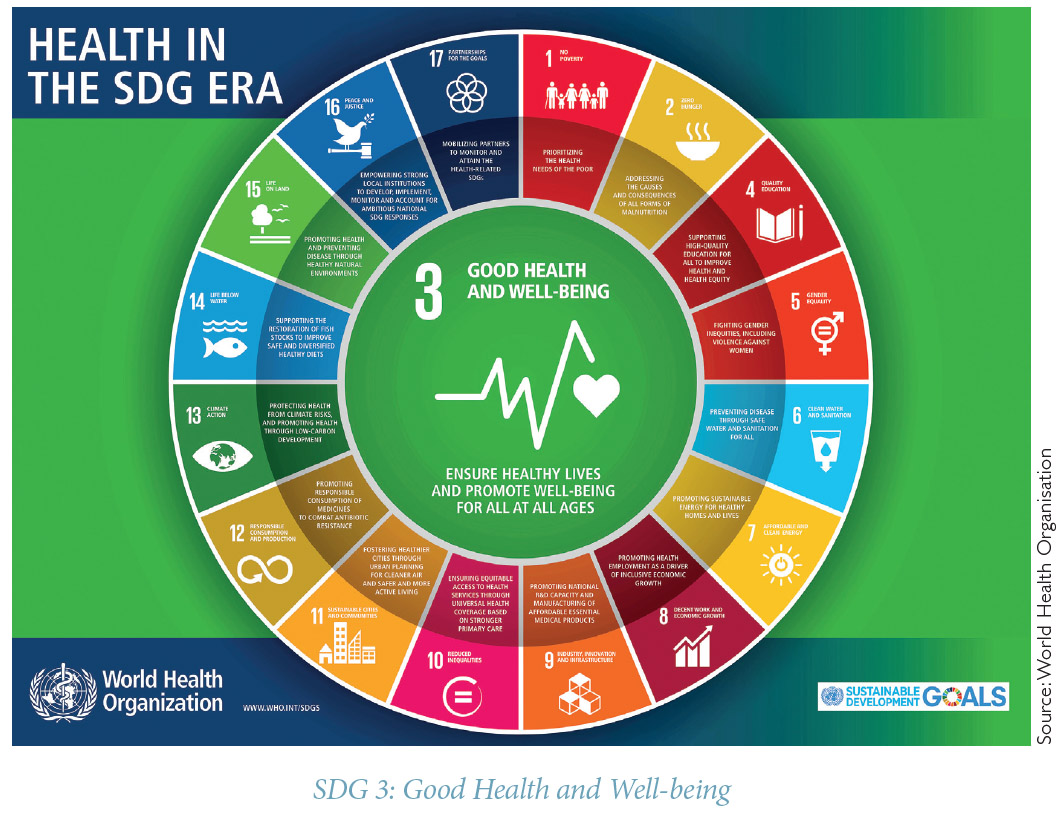

Increased attention is being paid to the private sector in the pursuit of innovative financing solutions to help address the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including those related to global health problems. Impact investing is one example of how private sector capital can be chanelled into global health, which receives billions of dollars in development aid annually. As part of the broader area of socially responsible investing, impact investing offers a sustainable way of advancing social and environmental causes while earning financial returns.

Global Health Security

But before we discuss the hows and whys of this surge of private partners for social good, it is important to affirm consensus on the question of why invest in global health?

Extraordinary changes in transportation, communication, and computer technologies have ratcheted up the pace and degree of global integration, interconnectedness, and interdependence. The oft-repeated case for ensuring global health security is to be found in the fact that all countries, regardless of size or clout, are today vulnerable to the looming threat of infectious disease epidemics.

As an apt illustration of this sort of global integration (not to mention the indiscriminate nature of pathogens), consider a case from 2014. An American medical colleague was preparing to leave New York City for Sierra Leone, to support Ebola containment efforts in West Africa. Just days prior to her departure, a fellow American physician, Dr. Craig Spencer, who had recently returned from treating Ebola patients in Guinea, tested positive for Ebola at New York’s own Bellevue Hospital Center. In effect, the deadly virus she sought to help contain on the other side of the world had made its way to her through a series of transcontinental flights.

The argument for sustainable and cost-effective health preparedness locally, regionally, and globally is obvious in light of the need to reduce the risk and harm of biological threats. To say the least, the impacts of global health crises are far-reaching in our increasingly interconnected world.

Beyond stemming continuous communicable threats, global health security faces increasing pressure from a more pervasive enemy: non-communicable diseases (NCDs). NCDs refer to medical conditions not caused by infections that can progress slowly and tend to be of a long duration. They cover a range of chronic illnesses, including cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, and chronic respiratory illnesses, and account for the deaths of 40 million people annually—making them the leading cause of death worldwide, according to the World Health Organization. The same source says that NCDs claim the lives of 15 million people aged between 30 and 69 annually, and over 80 percent of premature deaths caused by NCDs globally occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Hence, the evidence supports the claim that while NCDs can affect people of all ages and countries, their impact is far greater on the poor and middle-aged.