John Danilovich is the outgoing Secretary General of the International Chamber of Commerce. He previously served as U.S. Ambassador to Brazil and Costa Rica, and is a former CEO of the Millennium Challenge Corporation. You may follow him on Twitter @JohnDanilovich.

John Danilovich is the outgoing Secretary General of the International Chamber of Commerce. He previously served as U.S. Ambassador to Brazil and Costa Rica, and is a former CEO of the Millennium Challenge Corporation. You may follow him on Twitter @JohnDanilovich.

The huge growth of American industry and the concurrent expansion of the global economy following the end of World War I were so robust that we still refer to that era as the “Roaring Twenties.”

But the roar turned to a whimper as tariffs, trade wars, and ill-conceived restrictive government policies resulted in drastic declines in production, severe unemployment, and acute deflation throughout the world. These protectionist measures resulted in the Great Depression and the harshest economic and social adversity faced worldwide during the preceding 50 years.

In the current geopolitical landscape, world leaders would do well to prevent history from repeating itself in such a devastating way.

The importance of international trade was brought home to me when I served as U.S. Ambassador to Costa Rica from 2001 to 2004, and subsequently as U.S. Ambassador to Brazil from 2004 to 2005.

Costa Rica was the leading country among the Centrals in the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA), an expansion of NAFTA to include five central American nations (Costa Rica, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua) and the Dominican Republic. Taking effect in January 2006, CAFTA’s purpose was to eliminate tariffs and trade barriers and expand regional opportunities, which subsequently brought major economic benefits to the participating countries.

Brazil is America’s eighth largest trading partner and an essential market for most Fortune 500 companies. The U.S.-Brazil relationship began in the 1920s, with Henry Ford’s fabled trips to the Amazon to extract rubber for his car tires. Today, this trade relationship underpins a million jobs in the United States and Brazil. To cite just one extraordinary example, over 400 component manufacturers in the United States depend on business from Embraer—the Brazilian aircraft manufacturer.

With two-way goods and services trade between Brazil and the United States having tripled over the past decade, to total more than $100 billion, this dynamic and robust trade relationship is vital to support economic growth and job creation in both countries.

These in-country experiences, combined with my time as CEO of the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC)—a unique and innovative foreign aid program—and as Secretary General of the International Chamber of Commerce, have brought home a realization that so much of what has become our accepted way of life is the result of an open, global trading system.

Trade Matters to Everyone

Every piece of clothing we wear and every piece of technology we use is the result of a supply chain that stretches across the globe.

Everyone, every day, perhaps unknowingly, uses products that originate from many different countries, their components and raw materials drawn together by the global economy into a finished item.

What’s more, every individual is an actor in free trade. When a family from Europe takes a vacation in the Caribbean, it is engaging in international trade. When a foreign student withdraws money on campus from her home bank account, she is part of the global economy. The explosion of research, innovation, and manufacturing across the world has blurred borders and done away with the constraints of geography.

And yet free trade is about more than the simple provision of goods and services; it has also been the means by which we have liberated millions of our fellow human beings from poverty, ill health, and illiteracy.

According to the World Bank, in the last three decades we witnessed the greatest single decrease in material human deprivation throughout all of recorded history.

At a time when the population of the developing world has increased by almost 60 percent, the number of those in extreme poverty has dropped from around 50 percent to around 20 percent—a phenomenal achievement.

Four years ago, when I was approached to become Secretary General of the International Chamber of Commerce, I envisaged my prospective tenure as the head of the world’s largest business organization in a very different political context to the one we face today.

At that time, the case for global economic integration was clear and, what’s more, adopted by consensus. Governments focused their efforts on expending and accelerating trade growth as a means of building their economies. Like many others, I failed to see the wave of anti-globalization and populist sentiment coming our way.

While believing firmly in free trade and free enterprise, I am also fully aware that the global trading system is not perfect—as with everything, perfection is elusive, a work in progress. Despite the obvious overall gains, trade has had negative effects in some parts of the economy, and on some people’s lives.

Our responsibility is to correct those shortcomings, and to more rapidly assess their impact. We must work harder to spread the benefits of trade further and wider, and we must find ways to bring those who have lost out—or become marginalized—back into the mainstream.

But we would be betraying those very same people, and many, many more, if we turned against trade and allowed the negative rhetoric we have seen in recent years to go unchallenged.

Keeping Markets Open

Global economic powerhouses like China and the United States must not now turn their backs on open trade.

In large part, the United States is the author of today’s global trading system, and its positive economic impact is something of which Washington should be proud and should continue to build up and pursue. American leadership opened the global economy up to trade after World War II, as a means of building a more peaceful and prosperous world. And it is American leadership that can move us all forward now.

The Truth about Trade Agreements

There is no better starting point for a discussion on the current debate around international trade than NAFTA, which united Mexico, Canada, and the United States in the largest economic trading zone the world has ever known. NAFTA was—in large part—the product of American President George H.W. Bush, who launched and spearheaded the negotiations through to a near successful conclusion during his term in office.

NAFTA has long been a populist punching bag. Remember Donald Trump’s anti-NAFTA sentiment during the election campaign? He has even gone so far as to call NAFTA “the single worst trade deal ever approved in this country.” It is not.

With the passage of over two decades since NAFTA came into force, and considering the evolving economic realities that have since emerged, the agreement is certainly due a reassessment and re-negotiation. After all, the internet as we know it today did not even exist when NAFTA took effect. But it is in nobody’s interest to rip it up or roll it back.

When NAFTA took effect in 1994, it eliminated tariffs on more than half of its members’ industrial products. Over the next 15 years, the deal eliminated tariffs on all industrial and agricultural goods. Americans hoped that lowering trade barriers would foster growth in cross-border supply chains—a “Factory North America”—to rival those in Europe and Asia.

By moving parts of their supply chains to Mexico, where labor costs were lower, American companies could cut costs and improve their global competitiveness. American consumers would also benefit from cheaper goods. In return, Mexico sought improved access to the massive American market, and greater integration of its businesses within North American supply chains.

Both countries hoped the deal would boost Mexico’s economy, raising living standards and reducing the flow of migrants northward.

The truth is that after more than two decades, the three countries of North America are more economically integrated than ever. Trade between the United States and Mexico doubled as a proportion of GDP between 1994 and 2015. Mexico’s real income per person, on a purchasing-power-parity basis, has risen from about $10,000 in 1994 to $19,000 today. Recent trends also show that the number of Mexicans migrating to the United States has fallen.

But unexpected shocks prevented the NAFTA deal from achieving its full potential.

Both the peso crisis of 1994 and the 2008 global financial crisis inflicted blows to trade between the two countries. The rapid, disruptive growth of China also interfered with North American integration with the Chinese economy—accounting for more than 13 percent of global exports and around 25 percent of global manufacturing value-add. This has exerted an irresistible pull on global supply chains.

Despite these shocks, the hard evidence paints a very different picture to the popular narrative that NAFTA is responsible for the woes of the American workforce.

According to Brad DeLong, an economic historian at the University of California, Berkeley, NAFTA could be blamed for net job losses equating to 0.1 percent of the American labor force. That’s fewer jobs than the American economy adds in a typical month.

And even without NAFTA, American manufacturing jobs would have dwindled. The strong U.S. dollar and better transport and communications technology have rendered production abroad more attractive. In fact, automation has hastened the persistent long-term decline in industrial employment that is familiar in all rich economies—including in export powerhouses like Germany.

Most importantly, the failure to agree on a trade deal with Canada and Mexico would not have altered American geography. That is to say, the continent is a large and contiguous landmass—from the north of Canada to the Colombian border—rendering it economically interdependent. To take just one example: Canada is the top export customer for 36 U.S. states, a relationship that supports millions of jobs on both sides of the United States-Canada border.

Trade is not a Zero-Sum Game

It is understandable that some of us might see globalization as a zero-sum affair. Stagnant pay, rising inequality, and government complacency as industrial regions suffered long-term decline, have obscured the benefits of trade and created fertile ground for populists.

In many advanced economies—particularly in Europe—people see the burgeoning economic power of China, India, and the emerging economies as threatening jobs and stability.

What has also changed is the interplay between globalization, immigration, and terrorism.

Citizens the world over are suddenly feeling threatened: physically, from terrorism; culturally, as new waves of migrants change our societies with their customs and traditions; and economically, because an open world economy is increasingly sharpening competition. People feel less secure in all respects, and they feel that globalization has benefitted the few at the expense of the many.

But what we have seen in recent years is a radical blurring of left and right when it comes to the debate on global trade. In his first Joint Address to the U.S. Congress, Trump said: “I believe strongly in free trade. But it also has to be fair trade.” This newly deployed notion of “fair trade” is alarming for those of us who believe in

open economies and multilateral cooperation.

Totally misunderstanding the fact that the alternative to a rules-based trading system is one based on raw state power, the radical left has for years decried trade integration—and the World Trade Organization (WTO) in particular—as an instrument of big business.

When protests disrupted the WTO’s ministerial summit in Seattle in 1999, left-wing commentators exultantly proclaimed that developing countries were “finally standing up” against the dictatorship of multinationals backed by the United States and Europe.

And now, from the opposite ideological standpoint, several right-wing administrations appear to agree. In the name of national sovereignty, they insist on “taking power back.”

It is claimed that developing economies, most notably China’s, have benefited from trade, while workers in developed economies have lost out. It is claimed that if other countries are “stealing” jobs, then it makes sense to retaliate by putting tariffs on the goods we import from them.

This new notion of “fair trade” is nothing more than a proxy for protectionism; a facile, semantic sleight of hand; a free trade/fair trade word swap.

The answer to the question of whether this is the right way to address challenges arising from globalization lies in a straightforward assessment of whether protectionism and isolationism work.

The rationale for Trump’s recent decision to impose steep tariffs on a long list of Chinese imports may, on the surface, appear obvious: cheaper Asian imports flood American markets and cost American jobs.

But the economics are not quite so obvious.

The impact of these tariffs means higher prices for consumers—and, ultimately, less choice. One study suggests that American consumers will pay more than $2 million in higher prices for every domestic manufacturing job created.

What’s more, the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington estimates that protectionist measures would cut several percentage points from per capita income in the United States, with the poorest being the hardest hit, as prices of consumer goods rise.

Meanwhile, we see the leaders of some other major economic powers taking a fundamentally different approach.

At last year’s World Economic Forum gathering in Davos, the four “M’s”—Macron, May, Merkel, and Modi—each made a robust defense of trade and globalization, as did Justin Trudeau of Canada and Shinzo Abe of Japan. Eleven of the trading partners with whom the United States negotiated the Trans-Pacific Partnership have also chosen to move ahead—without the United States—on implementing the most ambitious trade deal ever agreed. Leadership, together with international cooperation, was the best way forward.

Tangible Trade Gains

By any objective measure, the world has done well out of global trade. Estimates show that the gains from trade have raised real household incomes on an annual basis. Trade means more choice for consumers. It also means lower prices, ensuring the money in one’s pocket goes further.

Companies that trade are more competitive. In the United States for example, export-related jobs pay more; in fact, between 13 and 18 percent more. But objective analysis highlighting the benefits of trade is of little comfort to someone who has lost his job, or is working more than one job to make ends meet.

In this context, it is quite understandable that trade has become a convenient scapegoat for populist politicians. The growing hostility to trade and globalization is, in many ways, a triumph of emotion over fact.

We need only to look at the threat of a U.S.-China trade war or the Brexit vote in the United Kingdom; or, perhaps, at the poll ratings of populist political parties throughout Europe.

In Business We Trust

So, how should we respond to this challenge? I believe that the answer lies with the global business community. In 1919, after the ravages of World War I, the League of Nations was created by governments for governments. At the same time, the International Chamber of Commerce was founded by business for business. The mandate of this world business organization was to promote peace and prosperity through international trade.

The group of industrialists that founded the ICC called themselves the Merchants

of Peace.

Almost 100 years later, the business community must assume this mantle once again, with the courage of their conviction that free trade is—and has proven to be—the surest way to economic prosperity.

We seem to live in an era in which trust in all institutions—government, civil society, the media—and business is at a low ebb.

The ICC believes in what has already worked to make advanced economies the economic powerhouses what they are today. Business is the last bulwark against the dark forces of populism, atavistic protectionism, and economic nationalism.

In this respect, I see four principal priorities for the global business community. First, business must take a stand to rebalance the public debate on global trade integration. For decades, the nuts and bolts of trade policymaking has been a technocratic pursuit largely without any degree of mainstream public engagement. Those days are now gone.

In an attempt to communicate more successfully on the benefits of trade, the International Chamber of Commerce has launched a major global campaign called “Trade Matters.” The campaign aims to reclaim the popular narrative around global trade, to help make a positive—and evidence-based—case for world trade. And to do so in a way that means something to the public at large.

Second, the private sector must help governments chart a new course for global trade policymaking that places “inclusion” at its heart. In this context, it is important to acknowledge that the benefits of trade do not reach as many people as they could—or should.

We must respond to these concerns, and to the very real problems that they represent, not by attacking trade, but by making trade policies work to drive inclusive growth.

Governments connect directly with the challenges people face through a new generation of trade talks, to open trade in goods and services up to new players in developing and developed countries; support for small businesses; and to harness the power of e-commerce to support inclusive growth.

Third, business must work with governments at the national level to shape policies and partnerships that address labor market dislocations.

While international trade has fueled growth and development around the world, it is principally the task of domestic policy to ensure that countries are ready to compete in a globalized economy and share the benefits of globalization in an equitable way.

There is no silver bullet or one-size-fits-all approach, but, whatever the chosen path, we must understand that action is needed across all governments and in close partnership with the private sector.

Despite the prevailing rhetoric, evidence shows that well over 80 percent of job losses in advanced economies are not due to trade, but rather to increased productivity through technology and innovation. And the reality is that jobs are at risk today due to technological advances that were thought nearly impossible just a few years ago: from self-driving trucks and cars, to advanced robotics powered by artificial intelligence. Studies suggest that almost 50 percent of existing jobs in advanced economies are at high risk of automation.

And that is just the average. In some sectors, over 80 percent of jobs are at risk. That is why more active and cross-cutting labor market policies will be essential in the years to come, including aspects of finance policy, education and skills, and improved support for the unemployed. There are already some tremendous examples of urban regeneration projects in the United States, such as the one in Pittsburgh, where the public and private sectors have worked hand in hand to diversify local economies and create new, high-quality jobs.

It is clear that an active and creative approach to addressing economic dislocation at the domestic level can deliver a great deal. However, this will require genuine political leadership, allied with real commitment from the private sector.

Finally, the private sector must show—through its actions—that business is a genuine force for good in society. Or, to put it differently: we must demonstrate that profit comes with a real purpose.

According to the 2018 Edelman Trust Report, three-quarters of the general population believe that business can take actions that both increase profits and improve wider economic and social conditions. Over half the general public believes that addressing societal needs in everyday operations is important for business to build trust with its employees, clients, and consumers.

We also know that the brightest graduates from the best colleges around the world increasingly want to work for companies that embrace the “triple bottom line” of economic performance, social responsibility, and environmental sustainability.

The young have high expectations of business—and we must rise to this challenge. The good news is that this challenge is also an opportunity.

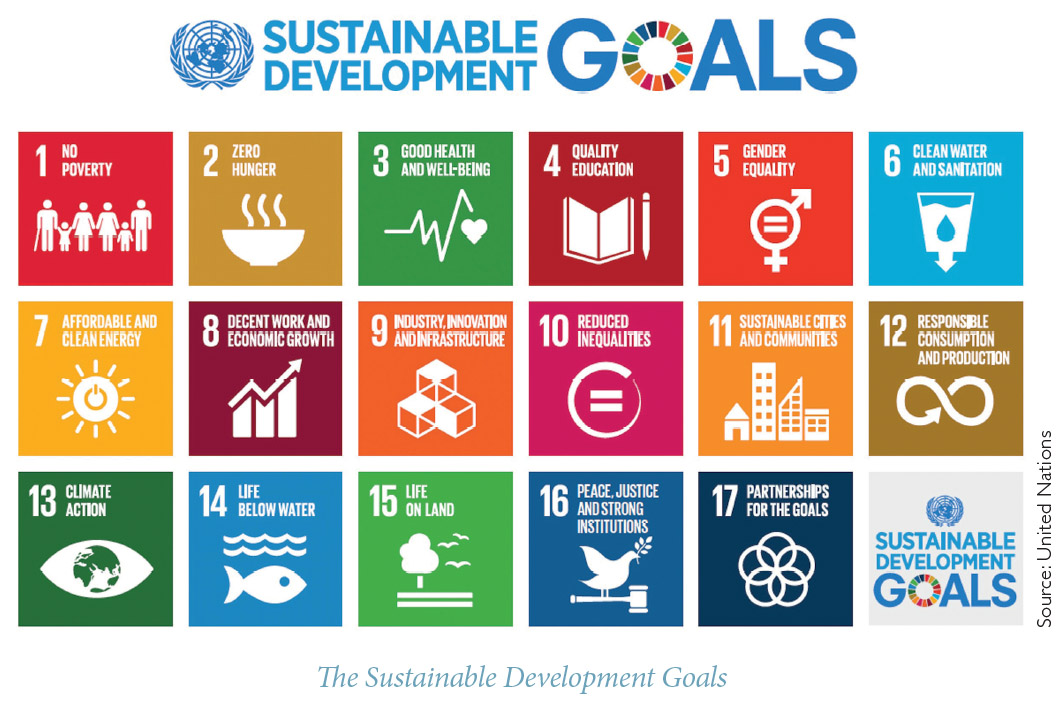

The groundbreaking report from the Business and Sustainable Development Commission, of which I am a Commissioner, shows that business engagement on the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is not only a powerful way to enhance society’s trust, but also a great business opportunity.

Business Development Goals

The SDGs are a common roadmap adopted unanimously by world leaders in 2015, for “people, planet, and prosperity.” It is estimated that the process of achieving the SDGs is creating market opportunities worth $12 trillion in sectors such as food, energy, health, and cities.

Markets specifically aligned with the UN’s sustainable development goals have the potential to grow three times faster than average GDP over the next five years, with half of those opportunities in developing countries.

We also know that companies with high ratings for environmental, social, and governance factors outperform the market and offer higher returns to investors over the medium term.

That is why, since their inception in 2015, I have said that the SDGs should also be known as the ‘BDGs’: the Business Development Goals. Many companies are already recognizing the major efficiency gains, innovation, and reputation enhancement that come with being socially and environmentally responsible.

More businesses must follow this lead: an indication of this leadership came last year when Larry Fink, Chairman and CEO of BlackRock (the world’s largest asset management company), sent out his annual letter to the companies in which BlackRock had invested.

He admonished those companies, which depend upon BlackRock’s investment, writing that, “every company must not only deliver financial performance, but also show how it makes a contribution to society.”

In today’s world, companies must be responsible for the societal impact of their operations. Without that, business will not succeed—and the United States will not prosper in the years to come.

It is clear that our response to the challenge of global change will define the future global political and socio-economic landscape.

There are answers. It is just that they will not be found through a retreat into protectionism, nationalism, or xenophobia.

The real answers combine the values that have underpinned the prosperity and stability we have enjoyed over the past several decades with pragmatic real time responses to the challenges we face in an increasingly complex world.

Business leaders must be ready to lead and engage in discussions. With the rise of populism, protectionism, and nativism, the world has reached an historic crossroads: one way leads to war, poverty, confrontation, and domination; the other leads to peace, development, cooperation, and

win-win solutions.

If we continue to trust in the model of free trade and free enterprise, and commit to ensuring that business is a force for good throughout society, we can be confident of a bright future for citizens everywhere.