S. Frederick Starr is Chairman of the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute and Silk Road Studies Program and Distinguished Fellow for Eurasia at the American Foreign Policy Council. This essay has been adapted from a study prepared initially for the Asia Development Bank.

S. Frederick Starr is Chairman of the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute and Silk Road Studies Program and Distinguished Fellow for Eurasia at the American Foreign Policy Council. This essay has been adapted from a study prepared initially for the Asia Development Bank.

Nearly three decades have passed since the Central Asian countries achieved independence—a necessary, although insufficient, prerequisite for a government to be able to plan and execute a national economic development strategy. Since the breakup of the Soviet Union, in one way or another, leaders from each of the region’s states have exerted conscious efforts to alleviate poverty and foster growth through cooperation with likeminded nations in Central Asia and beyond.

The pursuit of such strategies has contributed to the emergence of various regional initiatives, including the China-led Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). These have been largely responsible for a heightened level of connectivity within Central Asia and across Eurasia (understood in the broadest possible sense): a vast area bordered by four oceans: the Arctic to the north, the Indian to the south, the Pacific to the east, and the Atlantic to the west.

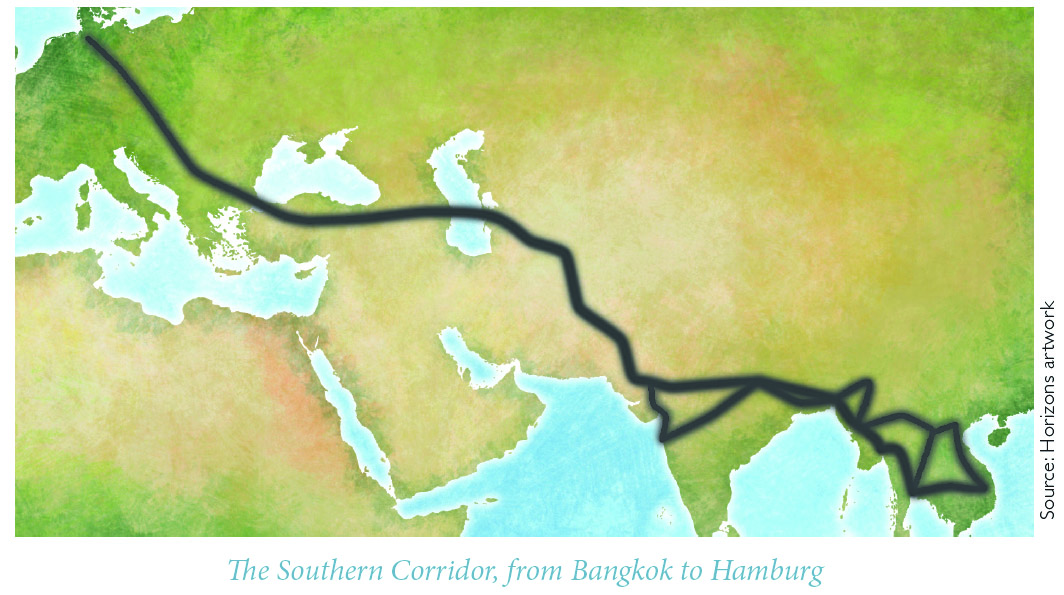

Despite significant advancements, the region’s infrastructure deficit has not been curtailed: virtually all areas of a demographically and economically booming Eurasian landmass continue to seek better infrastructure links. India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, for instance, demand greater infrastructure ties to European markets, as do the Central Asian countries and Afghanistan. While such needs require cross-border cooperation that supersedes political and economic rivalries, as well as a series of coordinated actions that seem far-fetched to some, one proposed networking super-project would go a long way to address these issues, namely the Southern Corridor.

The Southern Corridor endeavors to reconnect, via a series of land links, the economies of the Indian subcontinent with Europe and, ultimately, with South, East, and Southeast Asia. Thus, it builds on the existing efforts of states across Asia to advance regional integration and development through functional initiatives, directly affecting the economies of South and Central Asia, the Caucasus, China, and Europe. The project, however, does carry with it a degree of political risk. Although an important impediment, this obstacle can be circumvented through the prospect of accelerated economic development and mutually beneficial projects that help elevate its potential benefits above existing grievances.

A commitment to build the Southern Corridor could help usher in a new age of development and prosperity, whilst also helping to ameliorate the security and economic perils that loom in its absence.

What is the Southern Corridor?

The Southern Corridor is one of three historical trans-Eurasian land corridors, and the only one of these not functioning today. The youngest is the Northern Corridor, consisting of the Trans-Siberian railroad built by Tsarist Russia in the 1990s. The Middle Corridor is the ancient “Silk Road” connecting China and Europe. The Southern Corridor would connect the economies of Europe with India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, and, ultimately, with those further eastwards.

In examining the three corridors over the centuries, we begin with the fact that the Southern Corridor is the oldest, longest, least often interrupted, and most heavily used. Lapis lazuli from Afghanistan is found in very early Pharaonic tombs in Egypt, and also in Sri Lanka, while trade goods from the Indus Valley appear at archaeological sites in the Middle and Far East.

The ancient Silk Road between China and Europe arose in the first century BC and reached its apogee during China’s Tang dynasty until around 756AD, before flowering again briefly in the fifteenth century. By contrast, the Southern Corridor existed uninterrupted for 3,000 years until the establishment of the Soviet Union. Thanks to Uzbek scholar Edvard Rtveladze, we know that this route equally connected Central Asia—as well as the West—with India, and that the “Great India Road” westward from the Indus Valley was extremely heavily travelled, with caravans of up to 4,000 camels being common. Large settlements of Indian traders existed throughout the route, and as far afield as Baku, Constantinople, Bagan, and Hanoi.

Trade between the Indian subcontinent and Europe has burgeoned in the twenty-first century. The value of EU exports to India grew from $30.5 billion in 2006 to $41.78 billion in 2016, with engineering goods, gems and jewelry, other manufactured goods, and chemicals ranking at the top. According to IMF data, the value of EU imports from India also increased from $28.29 billion in 2006 to $43.52 billion in 2016, led by textiles and clothing, chemicals, and engineering goods. As a result, by 2016 the EU was India’s number one trading partner (13.5 percent of India’s overall trade with the world in 2015-16)—well ahead of China (10.8 percent), the United States (9.3 percent), UAE (7.7 percent), and Saudi Arabia (4.3 percent). India, in turn, was the EU’s ninth biggest trading partner in 2016, according to the European Commission.

These figures on East-West trade are dramatically enhanced when one considers other major economies that are directly on the route under discussion, namely Turkey in the west and Pakistan and Bangladesh in the east. Thus, to mention only Turkey’s trade with India, the Turkish government keeps records of exports rising from under $1.58 billion in 2006 to over $5.78 billion by 2016, with imports rising from under $222 million in 2006 to $651.70 million in 2016. Similar gains in terms of percentage growth were registered in trade between Turkey and both Bangladesh and Pakistan.

The total value of EU-Turkey exports to the Indian subcontinent was $37.5617 billion in 2006, rising to $54.43662 billion in 2010. This fell back to $51.7816 in 2016, but presently appears to be rising once more. EU-Turkey imports from the Indian subcontinent have grown significantly faster than exports, with the value of EU-Turkey imports growing from $41.554 billion in 2006 to $63.90529 billion in 2010, and then continuing to grow to $51.025 billion in 2016.

According to the IMF’s analysis, this difference is reflected in the balance of trade growing from $-9.46867 billion in 2010 to $-23.7455 billion in 2016. Overall, trade between Europe and Turkey, on the one hand, and India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, on the other, is already among the most dynamic components of world trade as a whole. A dramatic increase of trade in both directions began around 2008 and continues unabated today, with the only exception being a drop in Pakistan’s imports for several years after 2006.

To be sure, nearly all of these goods move today by ship. Indeed, certain large and heavy goods, such as massive machine tools and raw materials, should be transported on ships and always will be. Also, certain small and light weight items, such as computer chips or portable electronic gear, should be sent by air freight and always will be. But there remains a significant part of the total that can be most efficiently moved between East and West by road or rail. Many firms and freight forwarders in both Europe and India have estimated this figure for their own products. While their conclusions remain proprietary, it is clear that one-third to two-fifths of the total measured by value could be moved most efficiently by road or rail, provided these routes function effectively. The reason for this is the time factor, in which land transport has a decisive advantage over sea-based transport.

This, then, is the Southern Corridor idea in brief.

Emerging from the Unknown

It is reasonable to ask: if the Southern Corridor is so important, why do we hear so little about it? There are three reasons for this.

First, unlike China’s fabled BRI, the Southern Corridor up to now has had no name, let alone a highly evocative one. For centuries the route connecting the Indian sub-continent with Central Asia was called “The Great India Road,” but this term fell into disuse with the rise of the USSR. Recently, the government of Afghanistan has dubbed the route westward from Kabul to the Caucasus and Turkey the “Lapis Lazuli Corridor,” but this name only applies to part of the Southern Corridor and has yet to gain general usage.

A second reason scant attention has been devoted to the Southern Corridor is that the routes linking Europe and China have been under active development since 1991, while the Southern Corridor is only now becoming a topic of general discussion. Indeed, no sooner did the Soviet Union collapse than both China and the European Union stepped forward with projects to forge land-based connections between their economies. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) worked actively with China to develop the eastern side of this network, while the EU and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, through the Transport Corridor Europe-Caucasus-Central Asia (TRACECA) program, began developing the western side of the route through the Caucasus. By contrast, discussion of the Southern Corridor was nearly impossible during the period of Soviet invasion, civil war, and Taliban rule in Afghanistan, while seemingly insurmountable tensions between India and Pakistan further thwarted project planning, and even discussion.

The third and most important reason that the Southern Corridor has failed to become a major focus of discussion even among development experts is that all the major components that have been put in place to date have been funded and built by national governments rather than by international financial institutions or a single external power, as occurred with China’s funding of the Middle Corridor—i.e. BRI. Thus, since 2010, Turkey alone has invested at least $26.62 billion in the road, railroad, and pipelines that link its Mediterranean coast and the Bosporus with the Caspian, with Georgia and Azerbaijan now in the process of adding a further $2.5794 billion and $4.702 billion to build roads, railroads, and their new ports at Batumi and Alat.

Turkmenistan and Pakistan have invested at least $3.463 billion and $5.567 billion respectively in east-west corridor projects, according to the ADB’s CAREC program. Meanwhile, the Asian Development Bank, the United States, Germany, Italy, the World Bank, and Saudi Arabia, amongst other partners, have spent over $4 billion to build the Afghan Ring Road.

Each of these initiatives should be considered part of the single transport corridor connecting Europe and India. But it was easier, for a variety of practical reasons, for each state to proceed alone, albeit with de facto coordination, than to create and work through an overarching structure to plan and coordinate the larger enterprise. The convening of Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India to develop the TAPI pipeline is, thus, a rare exception to the highly decentralized system of transport planning that has existed to date along the Southern Corridor. Amazingly, this decentralization hasn’t led to fragmentation. But it has caused the larger program and the very substantial sums committed to its realization to be all but invisible, even to most specialists.

Growth Prospects

Notwithstanding the current global economic downturn and fragile recovery, the long-term prospects for growth along the Southern Corridor are bright. Demographic realities, accelerating growth already discernible in the Indian subcontinent, and the maturing of the economic boom in China, all favor this prospect. The opening of efficient transport between South Asian economies and with Europe and China would further stimulate the region encompassing the Southern Corridor.

This positive trend is already clearly discernible. While acknowledging that all projections are by their nature speculative, let us here report that the IMF has projected that the value of EU-Turkey exports to the Indian subcontinent will rise from $51.789 billion in 2016 to $72.079 billion in 2021—marking growth of nearly 40 percent. The IMF also estimates that the value of imports from the Indian subcontinent will rise from $75.527 billion in 2016 to $99.580 billion in 2021—or over 30 percent.

This data alone indicates the extent to which enormous new demands will be placed on transport facilities connecting Europe and India. Again, let us acknowledge that even if overland road and rail routes existed, they would probably carry only about a third of the total freight. But even if we accept this hypothetical estimate, it means that within five years at least $15 billion in goods annually would be likely to pass over land routes, if they were to exist.

But what about the longer-term prospects? It is important to stress that the data just presented does not acknowledge or respond to what may be the single most important factor affecting the future of trade between the Indian subcontinent and the West, namely the expected stunning demographic boom in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh over the coming two decades.

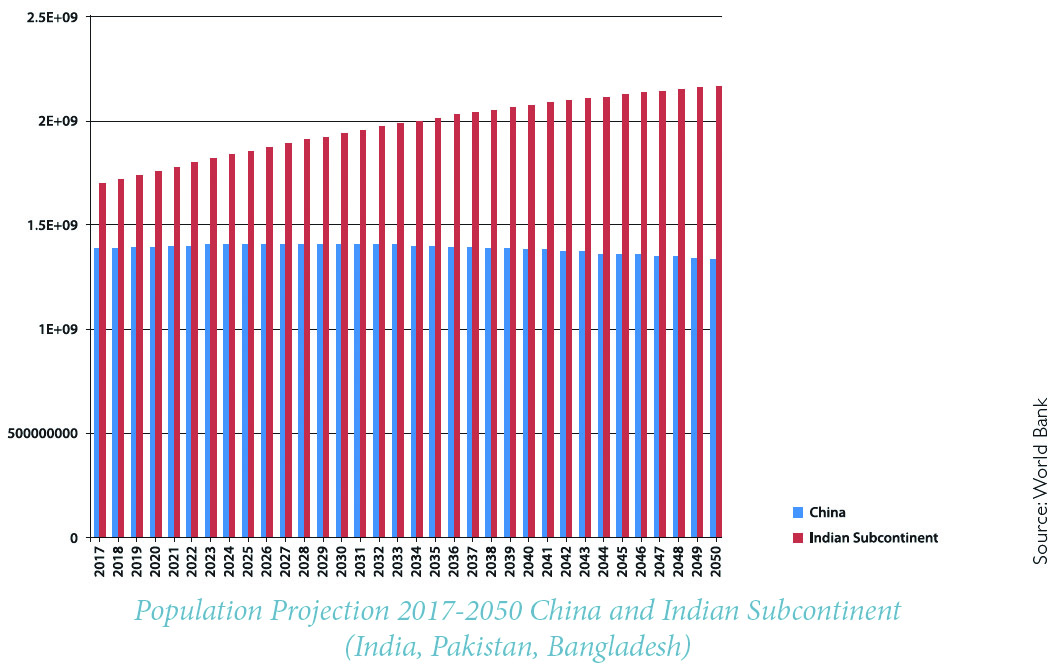

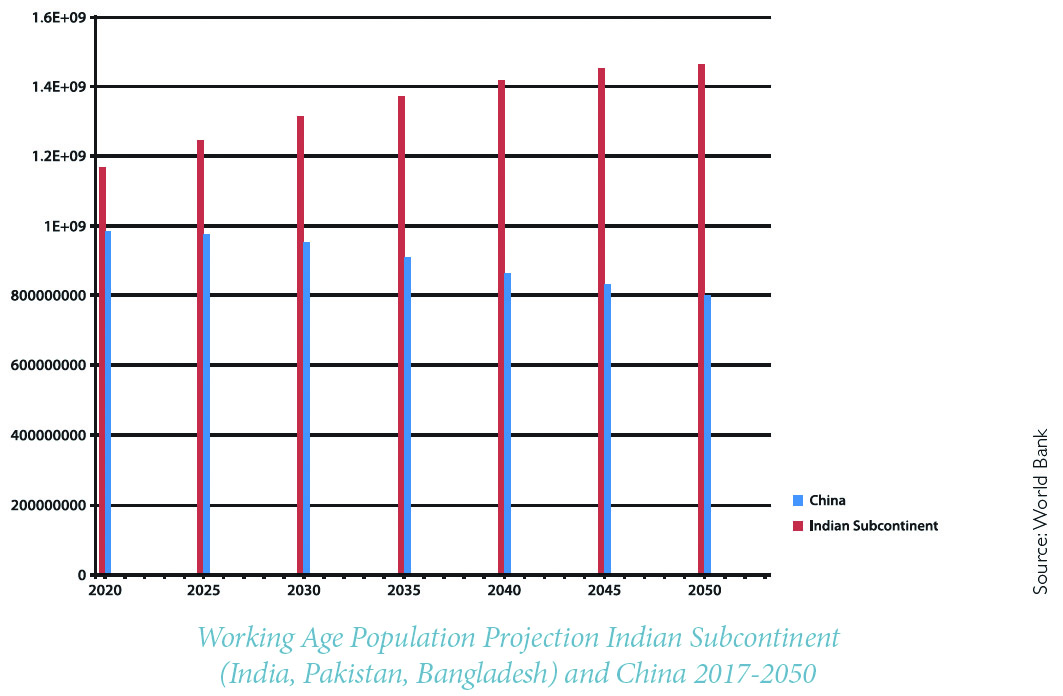

In the year 2000, China’s working age population stood at 865 million people and India’s was at 641 million. However, UN projections conclude that India will surpass China in population by 2025, and that China’s population by 2050 will be only approximately 799,014,054—a figure smaller than it is today. Since the demographic profiles of Pakistan and Bangladesh are similar to those of India, we can add their projected growth to the total for the subcontinent. The result is a population that will be more than half again larger than China’s by mid-century.

But this represents only part of the profound change impending in South Asia. Due to various demographic factors (among which China’s one-child policy figures prominently), the number of working age adults as a percent of the total population will be far greater in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh than in China. Statistical projections indicate the subcontinent will have a working age population of 1.46 billion in 2050, while China will have a working age population of only 800 million. This is a difference of approximately 663 million—that’s the equivalent of double the current population of the United States.

In short, there are solid reasons to conclude that prospects for growth in the use of the Southern Corridor are very strong, and undergirded by long-term economic and demographic trends that can be clearly discerned in the present.

Missing Components

How far are we from having a functioning Southern Corridor that can transport goods between Europe and South Asia by road and rail? Since 2001, the construction of hard infrastructure has proceeded apace across the region. Among the elements that have already been completed or are nearing completions are:

- road, railroad, and pipelines from Baku to Istanbul via Georgia;

- a new Caspian port at Alat, Azerbaijan;

- a new Caspian port at Turkmenbashi, Turkmenistan;

- a new road and rail link from Turkmenbashi to the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan border;

- the northern sector of Afghan Ring Road;

- a northern connector road between the new port at Gwadar and Afghanistan;

- the east-west grand trunk route across Pakistan;

- a new railroad across the belt of India;

- new competing ports at Gwadar, Pakistan, and Chabahar, Iran;

India’s construction of numerous roads and bridges in Bangladesh.

Other roads and bridges linking Central Asia and Afghanistan have been built by the United States, China, and Iran, with major support from other involved Central Asian countries.

This leaves several major hard infrastructure tasks yet to be accomplished. Among them are the following:

- a deep-water port in Georgia to facilitate transport westward from the Southern Corridor by sea;

- road and rail connectivity between the Turkmen-Afghan border and the Afghan ring road;

- a railroad along the Afghan Ring Road to connect Turkmenistan and Pakistan;

- either a railroad crossing from the Herat area to Kandahar or a railroad heading south to Kandahar from Kabul;

- a short road and rail link between Kandahar and the Gwadar-Islamabad route (this would require only a very short passage through Baluchistan);

- a road and rail route across southern Pakistan and improved connectivity between Amritsar, India, and Lahore, Pakistan, by the Wagah-Attari road and railroad;

- the completion of a road and rail link from Afghanistan’s Ring Road to Iran’s new port at Chabahar;

- the application of new technologies to adjust to differing track gauges (already done at Caspian ports).

"Soft infrastructure” remains a serious challenge across the entire route from Istanbul to India and northward to Central Asia. Among tasks in this area are:

- faster borders at the few key corridor crossings, through reform and the application of new technologies;

- the adoption of agreements specifying the roles of national and international road and rail companies on international routes;

- the adoption of International Road Transport Union (IRU) standards across the region;

- the provision of regionally standardized insurance and storage for containers shipped by road or rail;

- information systems regarding conditions and access, as well as border delays, for all rail and road routes.

It is easy to overstate the difficulty of improving soft infrastructure. In Afghanistan and Pakistan, for example, one should not focus on all roads, but simply on the two main corridor routes. Similarly, delays on the Wagah-Attari corridor could be resolved relatively easily once the two economies develop the will to address them.

Opening the Southern Corridor

A crucially important conclusion from the previous analysis is that major elements of the Southern Corridor

are already in place or are being constructed, thanks mainly to the efforts of individual countries along the route. Because of this, a major effort on behalf of the Southern Corridor as a whole need not centrally involve all transit countries. All transit countries and commercial end users should, of course, be involved, but the main focus can and must be on the four key countries where impediments remain: Turkmenistan

Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India.

By opening the Southern Corridor with the aforementioned focus, Central Asian governments should continue their existing efforts to connect Central Asian economies to South Asia. However, this should be directed toward opening existing routes to the Southern Corridor in such a way as to ensure quick access by road and rail eastward to Pakistan, India, and beyond, and westward to Turkmenbashi and thence to the Caucasus, Turkey, and, eventually, Europe.

A further aspect of this new phase would be to open up road and rail connections that would give Central Asian economies and Russia access to both of the new ports being built on the Arabian Sea: Chabahar in Iran, and Gwadar in Pakistan. To date, the focus has been mainly on the route to Chabahar. However, Gwadar not only offers a shorter sea route to Southeast Asia, but rather by offering competition to the Iranian port it would inevitably help drive costs down for Central Asian and Afghan shippers. Moreover, Gwadar, if connected to Kandahar by road and rail, as suggested above, would enrich Afghanistan’s restive Pashtun region, thus building stability throughout Afghanistan. Hence, both ports are important.

Nearly all of the existing structures and relationships between Central Asia and China—especially those with a focus on economic wellbeing and infrastructure, such as BRI—will be relevant to a new focus on the Southern Corridor and its connections. However, several strategic adjustments would be necessary, among which are the following.

First, India would need to play a more involved role in these structures.

Second, closer contact would need to be established with Southern Corridor countries that are beyond the previously mentioned four—specifically Bangladesh and Azerbaijan. In this context, enhanced communication with the Southern Corridor’s future commercial “end users” will need to be of great importance, including business interests and relevant officials in EU-Turkey and the Indian subcontinent. Both of these could be accomplished by setting up periodic

consultations.

Third, and in the same spirit of consulting “end users,” closer liaison should be established with all existing multilateral associations supporting the expansion of trade along part or all of the Southern Corridor. Among these are the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), the Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO), the Shanghai Cooperation Oganization (SCO), the Heart of Asia-Istanbul Process, and the emerging intra-Central Asia consultative group.

Ameliorating Political Risks

One reason the Southern Corridor has been discussed so little is that it appears to be fraught with political risk throughout its entire length. Thus, an increasingly conservative and Sunni-Muslim oriented Turkey poses challenges to its partners in the Caucasus: Christian Georgia and secular but Shiite Azerbaijan. Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan are each building ports whose success depends on the other, but their relations remain cool. The unlikely partners in the TAPI project continue to quarrel in unproductive ways, while Afghanistan and Pakistan appear to have once more sunk into contentiousness after attempting to patch up their differences.

Under these circumstances, is it not imprudent and quixotic to promote a project that ultimately depends on cooperation? Is the political risk not so great as to kill any hopes for success?

It is not my intention to minimize any of the issues listed above. However, it is important to note that in every aforementioned case there also exist important forces and factors that could lead to cooperation. Moreover, the very process of identifying the Southern Corridor as a potential source of benefit to individual countries and the region as a whole would help balance consciousness of the risk with perceptions of the opportunities on offer, as well as the economic costs of inaction.

Critics or potential critics of the Southern Corridor will not go unchallenged. Indeed, there are powerful interests in every country that already support such a project—especially if it is championed by multilateral development banks and similar stakeholders. The Erdoğan government in Turkey already strongly supports it, and has invested heavily in key infrastructure elements. Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Turkmenistan all see their future role as part of an east-west “land Suez”, and consider such a project vital to the protection of their economies and, indeed, sovereignty. Despite their differences, Turkey, Georgia, and Azerbaijan see each other as valued partners in a shared enterprise, while Turkmenistan’s relations with Azerbaijan have expanded steadily in recent years, in spite of ongoing disagreements over the delineation of Caspian energy deposits. Afghanistan’s two post-Taliban presidents, Hamid Karzai and Ashraf Ghani, disagree on much, but both have strongly supported a major east-west transport corridor through their country and have been eager to enlist Pakistan, notwithstanding their differences with Islamabad. To date, however, these have been largely thwarted.

The two most intransigent political risks along the entire route are the Afghanistan-Pakistan border and the India-Pakistan border. In both cases, there are forces in each country that find that a spirit of enmity between the two neighbors serves their interests better than cooperation. Pessimists abound and, in the case of India-Pakistan relations, even predict a worsening of relations after the impending 2018 elections in Pakistan and 2019 elections in India.

Yet all three countries are quite capable of separating their interests from their passions. Why else would Pakistan have championed the TAPI project over two decades, agreeing to bring India into it in order to increase its chances of success? Why else would India remain committed to a project that depends entirely on Pakistan’s cooperation? The government of Pakistan has at times thwarted trade across its border with Afghanistan, yet new trucking firms based in Islamabad are among the most active shippers throughout Afghanistan, Central Asia, and clear to the Caucasus. Many were founded by former officers in the Pakistani army.

Registered trade between India and Pakistan is a paltry $2.5 billion a year, and intra-regional trade within the subcontinent is a mere 5 percent of all of the three countries’ officially registered trade—barely one fifth of the figure for Southeast Asia. But, as a 2016 paper of the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations argues, up to twice as much unregistered trade passes between India and Pakistan. Far from being illicit goods, this consists of household appliances and foodstuffs that would be registered if a normal border regimen existed. The fact that both Indians and Pakistanis resort to the inconvenience and expense of trading through Dubai reflects the existence of powerful and growing business interests favoring improved commercial relations between the two states.

As manufacturing expands in both India and Pakistan, and as both economies become increasingly dependent upon that sector, the opportunity cost of closed borders becomes increasingly apparent. Indeed, there is no more powerful force advocating the reduction of barriers to trans-border trade between India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan than the growing tendency within businesses and in governments to calculate the opportunity cost of not doing so.

There is no reason to think that this would reduce tensions arising from disagreements between Afghanistan and Pakistan over the Duran line or between Pakistan and India over Kashmir. But the prospects of profits have already led commercial and political interests in all three countries to expand their cross-border trade with one another, even as political and religious enmities continue. And all this has occurred without so much as a mention of long-distance transport and trade. If the continental dimension of eased cross-border activity were known to businesses and governments, it is bound to change the calculus in favor of more trade and more engagement.

Similarly, Central Asians do not appreciate the opportunity cost of their not being able to utilize the Southern Corridor to Europe, on the one hand, and South and Southeast Asia, on the other. An initial task of any project to move the Southern Corridor project forward would be to encourage all participating countries to estimate the savings and gains that would be brought by access to major markets through the Southern Corridor, and the annual cost of not having such access.

Finally, if any party proves intransigent, there remain the sea routes from Mumbai to Chabahar and from Southeast Asian ports to Gwadar. Both ports should be part of any Southern Corridor initiative. Good planning requires that all options be explored. In this instance, that would mean examining a number of possible land routes between India and Afghanistan: their cost and likely usage under various conditions. Whether or not this assumes a post-conflict situation is a question best left to politicians and is beyond the scope of this essay.

Advancing the Project

A redirection of focus to the Southern Corridor and associated links to enable Central Asians to access East-West trade through that route is entirely compatible with these nations’ existing goals and policies. The current state of multilateral planning and coordination needs to be only slightly shifted so as to serve the new direction, and the same is true for Central Asia’s network of think-tanks and official meetings. The main structural change would be the inclusion of India, engagement with SAARC, and regular interaction with the market-based “end users” of the new corridor: mainly in Europe and Turkey, and the Indian subcontinent.

This last point is of great importance, for the Southern Corridor project cannot succeed without it being conceived from the outset as a geographical whole, and without consultation with those in the private sector who would actually be its users.

It is important to stress that the goals and policies of Central Asian states would continue to be driven solely by economic considerations. In this respect, it might be contrasted with most, if not all, of the existing regional consultative structures, which tend to be driven significantly by politics.

An important challenge will be to achieve appropriate forms of coordination with China’s Belt and Road Initiative and the EU’s TRACECA. This can be achieved by various means. However, it would be premature at this point to attempt to specify the best mode of coordination between these two continent-spanning projects. Suffice to say that such coordination will be critical.

The most important determinate of whether advancing the Southern Corridor project will be a success depends on the manner the concept is explained and advanced. It bears reiterating that very few outside the immediate region have fully grasped the importance of the economic rise of India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, and its potential significance to continental trade extending from Thailand to Hamburg. The first challenge to face will thus be educational: to get transit countries and private sector end users to engage with the prospect of this fundamental development, and then to translate that engagement into concrete actions.

All this would require an active use of convening power, in which multilateral financial institutions come in handy. The active use of this power, and the focus of attention on economic benefits arising from a functioning Southern Corridor, would do more than anything else to dissolve the toxic zero-sum thinking that has delayed progress to date.

This is no abstraction. In order for all the diverse parties to come together to the extent required by this economic initiative, it will be essential for them to calculate soberly the opportunity cost of not doing so. This does not mean laying aside points of contention and conflict. Rather, it means embracing economic advancement as a process that can go forward even as sharp differences remain in other areas.

The Chance of Success

Any assessment of the political risk arising from promoting the Southern Corridor is evidently affected by the likelihood of success in that endeavor. One crucial variable in its favor is the fact that all countries along the Southern Corridor have already launched important infrastructure projects of their own that feed directly into the proposed continental network. Without minimizing the scale of infrastructure yet to be constructed, this means that it will be entirely feasible to focus on the practical economics of the Southern Corridor as they pertain to each country along the route. Moreover, it makes possible an early focus on market-based commercial “end users” in the East and West, whose engagement with the project will determine its long-term viability and the scale of the benefits it bestows on transit countries.

Can looming political risks be reduced? Skeptics rightly point out that neither CAREC, the Heart of Asia process, the Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO), nor other international collaborations have eased the most significant regional tensions.

It is, therefore, crucially important to note that no existing international effort has explicitly and emphatically been grounded in a rational and convincing vision of emerging continental trade along the Southern Corridor. Whereas the underlying logic and prospects of the China-Europe connection have swept away nearly all doubts on BRI’s validity, no one—let alone a major international financial institution—has made a compelling case for the Southern Corridor.

With no vision of the economic benefits that could arise from its construction, existing political risks remain unchallenged and unresolved. But if a large financial actor were to calculate and announce the likely scale of continental and regional trade along the Southern Corridor route, and then proceed to back efforts to remove impediments to its realization, this would impact dramatically on the calculations of all countries involved.

It cannot be the mission of international financial institutions to engage in the politics that underlie regional tensions. However, with their highly professional focus on economics, they are well positioned to point out the benefits of the proposed continental route and the opportunity costs that will be incurred if it is not developed. The key to success for such an effort will be to identify and proclaim to each country along the route the opportunity cost of non-participation. Whether and how participation affects on-going strains in the political sphere is up to each country to decide on its own.

Costs of Inaction

In economics, as in physics, there is no rigorous method for measuring the consequences of non-action. However, it is safe to assume that if Asia’s driving economic and political forces were to hold back from supporting the Southern Corridor, they would strengthen the likelihood that the status quo would continue in key member countries, or that current economic trends in the region would intensify. One can hypothesize this happening in three areas.

First, the continued economic stagnation and isolation of Afghanistan would engender social and political instability there for the foreseeable future. This would strengthen the Taliban and further open the country to foreign extremists fleeing Iraq and Syria.

Second, this would perpetuate the continued isolation of Central Asian countries from nearby and traditional trading partners in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India. Not only would this guarantee continued low levels of investment from the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia, but would prevent them from marketing their products (cotton, vegetables) and manufactured goods in South and Southeast Asia. In short, it would prevent Central Asian economies from achieving several of their key goals.

And finally, inaction would reduce the likelihood that economic interaction would promote the reduction of tensions between Pakistan and India. At the same time, the growing imbalance between China’s increasing access to land routes to Europe and India’s total dependence on sea lanes would be bound to foster tensions between these great powers in the Indian Ocean—specifically in the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea.

While the economic and security risks of inaction may or may not materialize, the Southern Corridor project would constitute a critical step towards ensuring that they are reduced to a minimum. In the event of success, though, initiating this project would prove nothing short of visionary.